Herbert Marcuse: Plans for a Reader on the History of Materialism (1936/38)

Sketches with Max Horkheimer (+ a letter by Ernst Bloch).

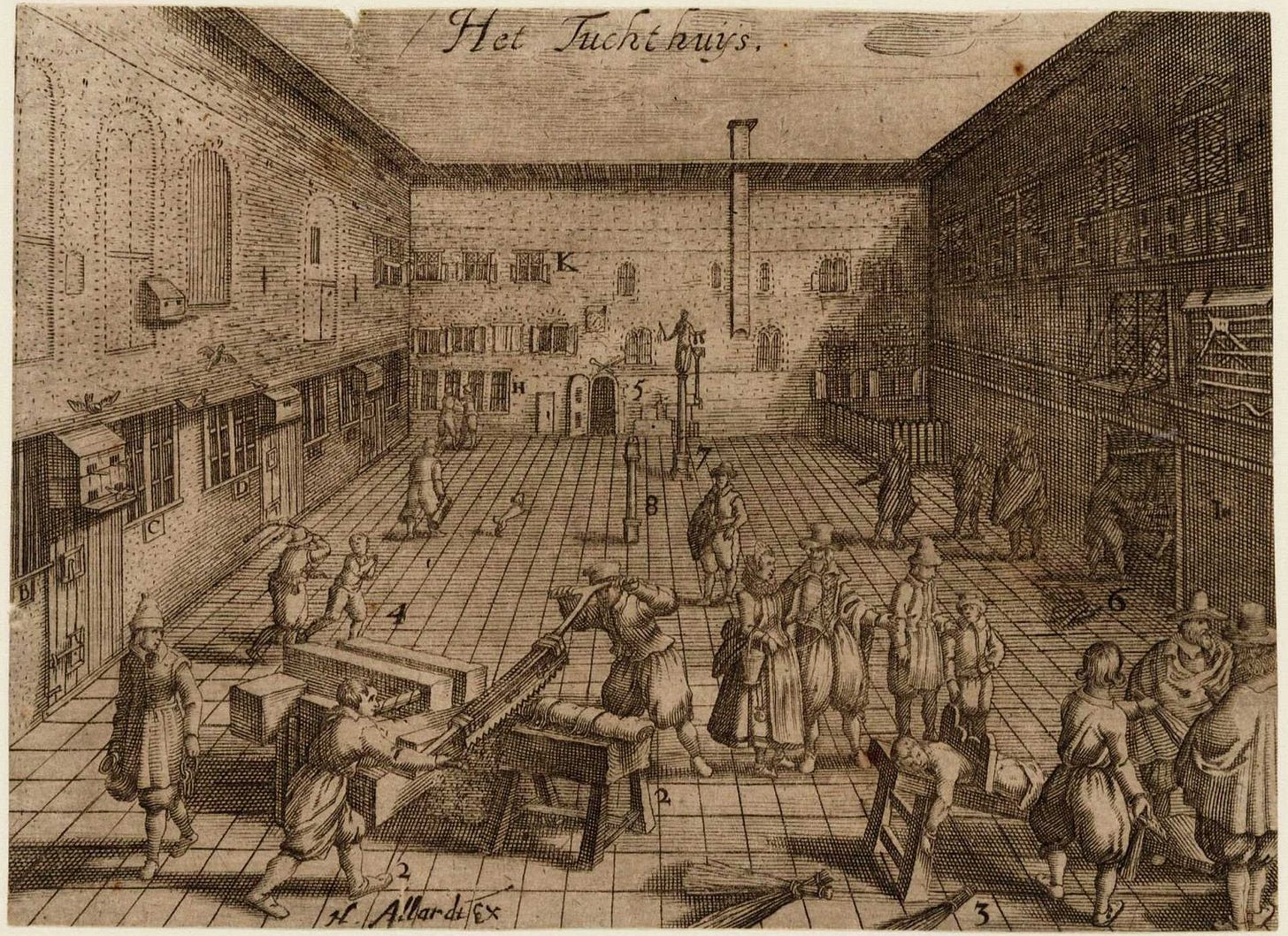

Adriaan Koerbagh does not merely translate theological, traditional, and religious concepts into their real, worldly, and socially ethical meaning. Instead, he systematically argues for an immanentist worldview on their basis. Doing so, he comes to radically subversive conclusions such as that sins are mere mistakes and that evil spirits are evil ideas; that disembodied things cannot appear; that the imagination may mislead us; and that ignorant people can easily be deceived. Religions seem irrational and can only maintain themselves in a political constellation when supported by deception and/or violence. It is therefore necessary to control them in the commonwealth, to interpret them with the use of worldly wisdom (i.e., philosophy), and to expose them, thereby dissipating their power in thin air. Immediately after Koerbagh had brought the explosive manuscript of Een Ligt [A Light Shining in Dark Places, to Illuminate the Main Questions of Theology and Religion]1 to the printer, he was arrested and sentenced to the Rasphuis in Amsterdam, where after less than a year, in 1669, he died, sick and broken due to the destructive circumstances, and brought to silence.2

Translator’s note. Three letters—from Marcuse, Horkheimer, and Ernst Bloch—on Marcuse’s plans for the unwritten Reader (Lesebuch) on the history of materialism in Western philosophy from antiquity through the late 19th century. Along with translations of the three letters, I’ve included an excerpt from Horkheimer’s 1936 “Authority and the Family” essay on Adriaan Koerbagh, “the fearless precursor and martyr of the Enlightenment,” as well as an excerpt of the ISR’s unpublished 1938 “Program,” in which Koerbagh is singled out as a model “materialist” heretic for the Reader. The two notes should be read as a promissory note for further research on Marcuse’s Reader in the future, including translations of the fragments he seems to have authored himself (such as the more extensive treatments of the Gnostics, his annotated bibliography of church heretics, his immanent critique of the repression of materialism within Leibniz’s thought, etc.).

—James/Crane (6/12/2025)

Contents.

Letters: Plans for a Reader on the History of Materialist Philosophy (5/6/1936)

Marcuse: The Plan for the Reader.

Horkheimer: Request—Quotations and Discretion.

Excerpt: Horkheimer on Adriaan Koerbagh in “Authority and the Family” (1936)

Letter: Ernst Bloch—from a Reader on the History of Materialism to a Reader on the History of Matter.

Excerpt: Text and Source Book on Critical Materialism in the History of Philosophy (1938)

Notes: On Marcuse’s plans for a Reader on the history of materialism.

§1. Marcuse: The ISR’s Philosophical Workhorse.

§2. The Historical-Philosophical Method of the Reader, or: Who is the Critical Materialist?

Letters: Plans for a Reader on the History of Materialist Philosophy (5/6/1936)

Recipients: Theodor W. Adorno, Walter Benjamin, Ernst Bloch (via Benjamin), Eduard Fuchs, Henryk Grossmann, Paul Honigsheim, and Hans Mayer.

Marcuse: The Plan for the Reader.

[Marcuse to Adorno & co., 5/6/1936.]3

We would be grateful for your advice and cooperation in the following matter. In view of the considerable confusion which presently prevails in the literature regarding the distinction between idealism and materialism, we are planning a reader which will cover the materialistic doctrines of Western philosophy from antiquity through the end of the 19th century. In particular, the aim of the reader is to express those tendencies of materialism which have been completely overlooked, or at the very least neglected, in the usual presentations on the topic. Above all, tendencies pertaining to the following problem areas: suffering and misery in history, the meaninglessness of the world, injustice and oppression, the critique of religion and morality, the connection between theory and historical practice, the demand for a better organization of society, and so on. The material is to be divided under the following main headings:

The task of theory.

History.

[The relationship of] human beings to nature.

[The relationship of] human beings to human beings.

The demand for happiness.

Critique of ideology.

The person of the materialist.

Accordingly, special consideration will be given to those thinkers who have been treated as outsiders [Außenseiter] or only mentioned in passing in official histories to date, as well as to the materialistic moments of non-materialists (such as Aristotle, Kant, Hegel), while, on the other hand, the materialistic philosophy of nature (e.g., ancient atomism) and so-called vulgar materialism will take a back seat. We would be grateful if you would bring our attention to things you think such a book should include (forgotten or little-noticed names and places). Beyond professional philosophers, heretics, literary figures, critics, economists, and sociologists should be taken into account. On the basis of your own studies, therefore, there is much you can contribute to the realization of our plan.

Horkheimer: Request—Quotations and Discretion.

[Horkheimer to Adorno & co., 5/6/1936.]4

I would like to add my personal request to that of Mr. Marcuse’s in the letter here enclosed. As we have placed the greatest value on engaging those philosophical and literary authors who have been rarely mentioned, misinterpreted, or left completely unnamed in official histories to date, we would be particularly grateful for any suggestions you might offer in this direction. Rather than providing a number of quotations, our intention is to provide fewer, more exhaustive ones. If you have the opportunity to send us excerpts from the texts of more unfamiliar writers of this sort, we ask that you quote the relevant passages in as little abridged form as possible. Should you seek the advice of a historian from your circle of acquaintances on this matter, we ask that you not inform him of our plans. Should the aim of our undertaking, which will likely require 1-2 years to complete, become generally known, there is a danger that the thought will be put into practice and exploited by the other side in a discrediting manner.

Excerpt: Horkheimer on Adriaan Koerbagh in “Authority and the Family” (1936)

The continuance of the bourgeois family by economic forces is supplemented by the mechanism of self-renewal which the family contains within itself. The working of the mechanism shows above all in the influence of parents on their children's marriages. When the purely material concern for a financially and socially advantageous marriage conflicts with the erotic desires of the young, the parents and especially the father usually bring to bear all the power they have. In the past, bourgeois and feudal circles had the weapon of disinheritance as well as moral and physical means of imposing the parental will. In addition, in the struggle against the unfettered impulses of love, the family had public opinion and civil law on its side. “The most cowardly and spineless men become implacable as soon as they are able to make their absolute parental authority prevail. The misuse of this authority is a sort of crude revenge for all the submissiveness and dependence they have had to show, willingly or not, in bourgeois society.” [Marx, “Peuchet: On Suicide” (1846)]5 When people in progressive seventeenth-century Holland were initially reluctant to persecute Adriaan Koerbagh, the fearless precursor and martyr of the Enlightenment, for his theoretical views, his enemies changed their tactics and focused on his living outside marriage with a woman and their child. The novels and plays of the bourgeois age, which were the literature of social criticism for the period, were filled with the struggles of love against being reduced to its familial form. In fact we may say that at the historical moment when enchained human powers no longer experienced their opposition to the status quo as essentially a conflict with particular institutions such as church and family, but attacked this whole way of life at its roots, specifically bourgeois literature came to an end. The tension between the family and the individual who resists its authority found expression not only in coercion against sons and daughters but also in the problem of adultery and of the murderess of her child. Treatment of this subject ranges from Kabbala and Love and The Awakening of Spring to the tragedy of Gretchen and Elective Affinities. In this area the classical and romantic periods, impressionism and expressionism, all voice one and the same complaint: the incongruity of love and its bourgeois form.6

Letter: Ernst Bloch—from a Reader on the History of Materialism to a Reader on the History of Matter (9/10/1936).

[Ernst Bloch to Max Horkheimer, 9/10/1936.]7

I’ve received your and Mr. Marcuse’s letters of May 6th by a rather indirect route.8 Timely plans seem to have the peculiarity of appearing twice. In November last year, in both Paris and Moscow, I suggested a materialistisches Lesebuch with texts from materialist writers. I made reference above all to non-mechanical materialists such as [Jean Baptiste] Robinet, but also to [Giordano] Bruno, and to the most peculiar concepts of “intelligible matter” (Avicebron) and of matter as the “womb of the forms” (Averroes). To this end, a friend of mine in Paris has already made some excerpts from the Fons vitae.

I had planned to write an introduction to the reader myself, which has since grown into a whole history of the concept of matter. This history has become the third chapter of my book, Theorie-Praxis der Materie, to appear next spring.9 As you can see, we are by happy coincidence pulling on the same thread. Whether my suggestion in Paris and Moscow has since become something more concrete, I do not know. In any event, I will inquire about it, if only so that the same work isn’t being undertaken independently in two places. It seems to me that your plan, judging by the scope of its problems, is broader. I myself was only fixed on the natural-scientific and metaphysical concept of matter.

I don’t know any historian who could draw on and make excerpts from material at the requested range. As for my own excerpts, I have already worked the greater part of them into the chapter on the history of matter, and they are mainly about the Aristotelian-Scholastic definition of matter as “possibility” [Möglichkeit]. Given the many, extremely instructive points of contact (and not merely equivocations) between such “possibility” and the procreative [Gebärenden], the unconcluded [Unabgeschlossenen] that lies so close to my heart, namely utopia, I would prefer to leave the above-mentioned excerpts where they’ve already been worked into the chapter and interpreted. In any case, my excerpts are not drawn from inaccessible sources, but are easy to find in Munk and Horten.10 I’ve also found promising references in the second volume of Stöckl’s Geschichte der Philosophie des Mittelalters.11 But I need not even bother with such pointers. Nor does any of this tackle the rather disturbing problem that the greatest philosophers were no materialists, but rather, one might say, crypto-materialists. The main thing here is the subsequent processing of the plate, and so a business of indirect, not direct, presentation.12

Excerpt: Text and Source Book on Critical Materialism in the History of Philosophy (1938)

[Excerpt from: An Institute for Social Research: Idea, Activity, and Program.]

Text and Source Book for the History of Philosophy. Traditional histories of philosophy differ from each other according to the emphases of the individual authors, whether they consider epistemological, metaphysical, or ethical doctrines to be more decisive. Past systems and schools are classified from such standpoints. The book which we have projected will approach philosophical theories from social problems and their solutions. Despite the enormous differences, every society in past historical eras has been divided into classes, and the general problems of philosophy are closely bound up with the problems resulting from such a social division. Precise analysis reveals that even in the most abstract theories of knowledge, reason, matter, or man, difficulties and tendencies are to be discovered which can only be comprehended from the struggle of mankind for liberation from restricting social forms. This textbook, therefore, will not be limited to strictly social philosophical problems but will also deal with the problems of so-called pure philosophy. Such an approach will bring to the fore philosophers who are hardly mentioned, if at all, in the traditional histories of philosophy. We might point to the heretical gnostics who virtually disappear behind the early church fathers, the radical Averroists who are hidden behind the Thomists, Adriaan Koerbagh, a contemporary of Spinoza, or the pre-revolutionary French thinker, the Abbé Meslier. Success and renown originate in uncontrollable and often hidden forces, not only in society itself but also in the memory of man. This is true of entire philosophical doctrines and of specific aspects. There are many sections within famous metaphysical and idealist systems which are virtually unknown, or are deliberately misinterpreted, because of their critical and materialist tendencies.

Research Notes: On Marcuse’s plans for a Reader on the history of materialism.

§1. Marcuse: The ISR’s Philosophical Workhorse.

In connection with the questions which revolve around logic, Marcuse is presently writing a treatise on [“The Concept of Essence”].13 He proceeds from the determination [of Marx’s] that without a distinction between essence and appearance, science would be superfluous.14 As it is well known, positivism completely denies the concept of essence, or rather flattens it to such a degree that it turns out to be only another banality. On the other hand, [Max Scheler’s] materiale Phänomenologie has proclaimed the idea of static essentialities [Wesenheiten] and, thereby, a new Neoplatonism, which has lead directly to mysticism as well as the hostility to spirit and science so characteristic of some intellectual currents of the present. Therefore, it seems high time to determine more precisely what is meant by the distinction between essence and appearance in a theoretical manner beyond reproach.

—Excerpt from Horkheimer’s Letter to K.A. & O. Wittfogel (10/29/1935)15

In this description of the idea behind Marcuse’s “The Concept of Essence” (1936), Horkheimer has set the bar high—perhaps too high. The full scope of philosophical positions towards the concept of ‘essence’ Horkheimer seems to expect Marcuse to address is staggering: from the dissolution of essence in neo-positivism to the hypostatization of essence in neo-metaphysics, including the mystical contemplation of essence in the Plotinian ascent towards the One as well as the critical function of essence in Marx’s critique of political economy. In the final product, Marcuse limits himself to the customary division in the history of western philosophy to ancient-medieval-modern, but still struggles to balance the conflicting methodological demands of the ‘internalist’ philosophical (re-)construction of the concept of essence and the ‘externalist’ historical-materialist criticism of the changing social content of the concept of essence. What reason, if any, would Horkheimer have to expect this much from Marcuse’s essay on the concept of essence?

For more on the failure of Marcuse’s ‘Essence’-essay on its own terms, see Mac Parker’s contribution to the CTWG’s Margin Notes, Volume 1, “Essence in the Archaic: Notes Towards a Historical Materialist Account of the Concept of Essence,” which takes Marcuse’s essay as a point of departure for developing an alternative model for historical materialist explanations of the social determination of philosophical thought—specifically by focusing on the emergence of the concept of essence in the matrix of class struggle in Ancient Greece.

After joining the ISR in exile from Geneva in 1933, Marcuse would write more than 45 separate reviews for the ISR’s Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung between 1934 and 1939. These included both focused reviews of individual works and broad surveys of works grouped according to theme (often, these collective reviews were of 4+ works at a time). The vast majority of these reviews seem to have been virtually forgotten in Marcuse reception and remain untranslated to date. Marcuse was hired by the ISR to serve as its resident ‘philosophical specialist,’ which apparently meant he was expected to specialize in the field of philosophy as a whole. This is reflected in the topics of his reviews for the ZfS, which range from critical remarks on philosophical-philological commentaries on the fragments of Heraclitus to studies on the cosmological systems of Renaissance poetry to the new canon of classics in logical positivism and American pragmatism. The task was largely a thankless one, despite the fact that Marcuse’s work served as an indispensable guide to the contemporary philosophical landscape for the other members and affiliates of the ISR as they pursued more focused projects within the ISR’s multidisciplinary research program.

Marcuse’s philosophical contributions to the formation of critical theory through the 1930s extend to the determination of the idea of ‘critical theory’ itself. Marcuse is the first to employ the ‘Aesopian’ euphemism of ‘critical theory’ in print after Horkheimer and develops the idea further in “Philosophy and Critical Theory” (1937),16 the companion piece Marcuse wrote for Horkheimer’s “Traditional and Critical Theory” (1937).17 In the following year, Marcuse writes another essay for the ZfS, “On Hedonism” (1938), in which he explains how ‘the critical theory of society’ came to have the form of Epicurean hedonism stripped of its former narrowness through a confrontation with the critical universalism of modern moral philosophy.18 This essay is a complement to Horkheimer’s own contribution to the same issue of the ZfS, “Montaigne and the Function of Skepticism” (1938), in which he explains how ‘the critical theory of society’ came to have the form of humanistic skepticism stripped of its former complacency and submissiveness through the recollection of its changing historical relationship with its double, religious dogmatism.19

If the core of the ISR devoted its efforts in the 1930s to laying the theoretical foundations for the critical theory of society, Marcuse’s contribution was a minimal, systematic survey of the history of Western philosophy—from Parmenides to John Dewey, and from a distinctively materialist perspective—his co-workers could use as a map for navigating both the canon and the contemporary academic institution of philosophy, often taking his constructions as a more ‘vulgar’-materialist (or -idealist!) foil against which they could stake out positions of their own. In this sense, the fact that so much of Marcuse’s work from this period has been forgotten is an indication of its success. What makes Marcuse’s plans for the Reader unique is not the ambitious scope of the project, but the novel methodological approach to the history of Western philosophy Marcuse began to develop for it.

§2. The Historical-Philosophical Method of the Reader, or: Who is the Critical Materialist?

The “Program” for the ISR Horkheimer drafted in 1938 lists the “Text and Source Book for the History of Philosophy” as one of the several books expected to be “completed within the next two years.” Instead, the plan for the Reader was abandoned in the turmoil of the years that followed. (In fact, none of the six books Horkheimer outlines in the ‘Program’ section would be completed or published in the form they were expected to take at the time the report was drafted.) The ISR’s long-term financial problems came to a crisis point in fall 1938, redirecting the group’s efforts to a series of unsuccessful campaigns to secure the funding they would need to remain an independent research collective. This process ended with the effective dissolution of the ISR in all but name in 1941, as almost all of its members were denied full-time positions at the academic institutions which had offered them sanctuary a few years prior. Between 1941 and 1943, the group would be dispersed across the east and west coasts of the continental United States, forced to seek non-academic employment or academic research funding through government agencies and non-profits which were created under or expanding as part of the American war effort.

However, the Herbert Marcuse Nachlass—much of which is digitized and freely available through Goethe Universität (Frankfurt am Main)—contains a number of detailed excerpts from the Reader project.20 Some are lengthy quotations (some of which Marcuse dug up himself, others seemingly from recipients of the May 1936 letter) and some are bibliographies (some are annotated, others are not) of both primary and secondary sources on the rogue’s gallery of “materialists”—cabbalists, pantheists, atheists, naturalists, hedonists, gnostics, deists, mystics, etc. What the Reader’s definition of “materialism” seems to lack in consistency of doctrine, it recover’s in consistency of what Horkheimer often called the Haltung (attitude, stance) or Gesinnung (conviction, ethos) of the materialist: the materialist gives voice to the suffering and misery of human history, the meaninglessness of the world, the triumph of injustice and perennial oppression; the materialist is a critic of established religion and morality, demands a better organization of society than they have any right to, confronts other-worldly contemplations with the vulgarities of this-worldly life, returns theoretical abstraction to social practice. The model for the materialist is the heretic. Like Adriaan Koerbagh, fearless precursor and martyr of the Enlightenment.21

Among the surviving materials, there are several short fragments for potential entries seemingly written by Marcuse himself. Some are more intuitive than others. For example: Marcuse writes a 2-page note on the tension between idealist and materialist moments in Leibniz's thought, or the constant re-conversion of concrete multiplicities discovered in modern scientific and philosophical thinking into the abstract, undisturbed unities of classical idealism. This fragment is in keeping with the intent of the Lesebuch-plan in 1936 and the 1938 “Text and Source Book for the History of Philosophy” prospectus: both propose the careful interpretation of idealistic philosophies for their overlooked critical-materialistic tendencies. Other fragments are much stranger. For example: another 2-page note on the life, thought, and associates of Johann Conrad Dippel (1673-1734), a German Pietist theologian, physician, and alchemist who published a number of theological works under the name of “Christianus Democritus;” Marcuse seems particularly struck by the connection between his heresies and his experimental chemistry.

Excluding the names I’ve been able to find in the correspondence—for instance, Walter Benjamin’s recommendation that the Reader include Gottfried Keller in a letter from December 1936; or Ernst Bloch’s shortlist of the ‘Aristotelian Left’ in the letter translated above from September that same year—the following is an incomplete list of figures on whom Marcuse began to collect materials for the Reader:

Heraclitus (ca. 6th-5th century BCE)

Alcidamas (5th-4th century BCE)

Protagoras (ca. 490–420 BCE)

Xenophanes (ca. 570-478 BCE)

Cerinthus (ca. 50-100 CE)

Ambrosius (St. Ambrose) (374-397 CE)

Basilius (St. Basil the Great / Basil of Caesarea) (330-379 CE)

Asterius (St. Asterius of Amasea) (ca. 350-410 CE)

Lactantius (ca. 250-325 CE)

Epiphanios (St. Epiphanius of Salamis) (ca. 310/320-403 CE)

Augustinius (St. Augustine) (354-430)

Johannes Scotus Erigena (John Scottus Eriugena) (ca. 815-877)

Marquis d’Argens (1704-1771)

Johann Friedrich Bachstrohm (1688-1742)

Mutian de Bath (1686?)

Carl Friedrich Bahrdt (1741-1792)

Laurent Angliviel de la Beaumelle (1726-1773)

Charles Blount (1654-1693)

Johann Hieronymus Boeswillibald (?-1768)

Guillaume-Hyacinthe Bougeant (1690-1743)

Henri de Boulainvilliers (1658-1722)

Thomas Brown (1778-1820)

Arthur Bury (1624-1714?)

Thomas Burnett (1656-1729)

Petro Chauvin (1693?)

Thomas Chubb (1679-1747)

Bernard Connor (c. 1666–1698)

Johann Gilbert Cooper (1722-1769)

Frans Kuyper (Cuperus) (1629-1691)

William Coward (1657?–1725)

John Dove (?-1772)

Willem Deurhof (1650-1717)

Johann Conrad Dippel (1673-1734)

Philadelphus (pseudonym of Gysbert Tyssens) (1693-1732)

Adam Köpke (1st 1/2 of 18th century)

Oswald Heinrich Ermeling (pseudonym of Johann Christian Behmer) (ca. 1688-1729)

Christian Gabriel Fischer (1686-1751)

G.W. Leibniz (1646-1716)

In some cases, the most important marks these “materialists” will have left behind in the annals of recorded history were submitted to the ruling authorities of class society by their accusers, as if Marcuse’s Reader were an anticipation of Michel Foucault’s anthology of the “Lives of Infamous Men” (1977). Following Foucault’s own approach, we can distinguish between his “Lives” and Marcuse’s Reader by formalizing a set of rules Marcuse laid down for himself:

The figures included in the Reader must be legible as philosophers, even or especially if their status as a philosopher is disputed, because of their participation in ‘philosophy’ as a contested historical form of discourse.22

The figures included in the Reader must either be the accused ‘materialist’ or their ‘crypto-materialist’ accusers in a major or minor controversy over a purported ‘heresy.’

If the figure of the materialist in the Reader is modeled on the heretic, this is because materialism becomes the model for heresy. The string of equivocations—cabbalist, pantheist, atheist, naturalist, hedonist, gnostic, deist, mystic, etc.—is spun together by the powers of this world in the history of confrontations between the isolated heretics of prehistory and the negative invariance of social domination in class society.23 The “materialists” in the pages of the Reader were caught, and often crushed, in the conflicts of the ancient poleis, Civitas dei and terrena, modern state and bürgerliche Gesellschaft.

In an unpublished review (ca. 1928/29) of Lenin’s Materialism and Empirio-Criticism (1909), Horkheimer draws a sharp distinction between materialism as a worldview and materialism as an organon:

The dialectical materialism of Marx and Engels contains no ‘worldview’ with which one can adapt to the dominant order. It is the organon of revolutionary upheaval that comprehends actuality from the point of view of forward-driving tendencies.24

For Marcuse and Horkheimer, there can be no ‘canon’ of materialism in the true sense, but only an organon for the reactivation of the force of thinking against the power of suggestion, “a sign of resistance, the effort to keep oneself from being deceived any longer.”25 This is the ultimate criterion for the Reader itself, well-expressed in two of the “fundamental principles” Horkheimer and Friedrich Pollock profess in a 1935 memorandum with each other:

[IX.] The right attitude towards society: results from keeping the following in mind: in society today, all human relationships are falsified; all kindness, all approval, all goodwill are, in a fundamental sense, never meant in earnest; what is serious is only the competition within each class and the struggle between them. All recognition, all success, all seemingly sympathetic interest comes from jailers who indifferently permit all of those without success and power to rot, or torture them to the point of bloodshed. All acts of kindness are shown not to the person, but to their position in society—and this is made manifest in all of its brutality whenever the person has lost their position through some minor or major change in the ongoing struggle (stock market, Jew-hatred). But this abstract insight is not what’s most important. You must always keep in mind that it is you—you yourself—who will be delivered over to the mercy of others when all of those people of kindness and goodwill you deal with on a daily basis discover that you have in fact become one of the powerless. Consequence: never on the side of the jailers; solidarity with the victims. (Note: There are in this society some human beings who are not merely its functionaries, particularly among women. But they are much rarer than one commonly assumes.)

[X.] The impossibility of being “liberal” and “objective” in the face of a variety of more or less plausible opinions results from the consideration: For any discovery to be fruitful, it must correspond to the following conditions: meet a need, in the context of the totality of experience, according to the state and structure of our cognition.26

Wielema, Michiel R., eds. Adriaan Koerbagh, A Light Shining in Dark Places, to Illuminate the Main Questions of Theology and Religion, (Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 11 Nov. 2011) doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004214583

Sonja Lavaert “Adriaan Koerbagh, “An Excellent Mathematician but a Wicked Fellow.”” In: Church History and Religious Culture, 2020, Vol. 100, No. 2/3, Special Issue: Confessional Clamor and Intellectual Indifferences (Brill, 2020), 271.

Marcuse to Adorno and co., 5/6/1936. In: Max Horkheimer, Gesammelte Schriften. Band 15 (1995), 517-518. Author’s translation.

Horkheimer to Adorno and co., 5/6/1936. In: Max Horkheimer, Gesammelte Schriften. Band 15 (1995), 518-519. Author’s translation.

Karl Marx, “Peuchet: Vom Selbstmord” [1846]. In: Marx-Engels, Gesamtausgabe, Part I, Vol. 3 (Berlin, 1932), p. 396.

English: “Peuchet: On Suicide.” Translated by Barbara Ruhemann. In: MECW Vol. 4: Marx and Engels 1844-1845. (Lawrence & Wishart [E-book], 2010), 597-612.

In: Critical Theory. Selected Essays by Max Horkheimer. Translated by Matthew J. O’Connell & co. (Continuum, 2002), 125-126.

Ernst Bloch to Max Horkheimer, 9/10/1936. In: MHGS, Bd. 15 (1995), 630-632. Author’s translation.

The letters of May 6th were sent via Walter Benjamin in Paris.

First published in 1972 under the title: Das Materialismusproblem, seine Geschichte und Substanz. In: Gesammelte Werke Bd. 7, (Suhrkamp: Frankfurt am Main, 1972)

Salomon Munk, Philosophie und philosophische Schriftsteller der Juden. Translated from the French by Dr. B. Beer (Leipzig: Verlag von Heinrich Hunger, 1852) [link].

Max Horten:

Die Metaphysik des Averroes (Halle a.S.: Verlag von Max Niemeyer, 1912) [link]

Die Hauptlehren des Averroes (A. Marcus und E. Webers Verlag: Bonn, 1913) [link]

“die Nachentwicklung der Platte”: a reference to the “Wet-Plate Collodion Process” in photography, which dates back to the 1850s: “To begin the process, the glass or metal plate is polished and carefully coated with a viscous solution of collodion to which an iodide and sometimes a bromide have been added. The plate is then made light-sensitive by placing it, while still tacky, into a solution of silver nitrate. After several minutes the plate is removed and placed into a plate holder, then placed in the camera. After exposure in the camera, usually five to ten seconds, the plate holder is removed and taken to the darkroom for development. Removed from the holder the plate is flowed with an acidic iron sulfate solution. Once adequately developed, the image is rinsed in water. The developed and rinsed plate is then fixed in hypo to remove unexposed silver salts, and washed again thoroughly under running water. The plate is dried over a gentle flame and usually varnished while still warm for protection. To create a collodion negative, the wet-plate image is produced on a transparent glass plate, which can then be used for printing on photosensitive paper in the same way as modern film negatives. To create an ambrotype (a collodion positive) the wet-plate image is produced on a glass plate which is either of a dark color, or is darkened behind the image. The unexposed, clear areas in the collodion image then show (correctly) as black in the ambrotype thanks to the dark glass or black backing behind them. To create a tintype, the wet-plate image is produced on a pre-blackened or japanned metal plate, with the same visual effect as an ambrotype. All steps of the wet-collodion process must be carried out on the spot and within ten minutes, with the plate kept continuously moist, or failure will result. The production of a wet-plate image is very much a “handicraft” and each wet-plate image will inevitably include process artifacts created by variations in the coating of the plate, the lengthy exposure time, and other factors.” [link]

ZfS Vol. 5 No. 1 [1936], 1-39.

Marx, Cap. V. III: “But all science would be superfluous if the outward appearance and the essence of things directly coincided.” [link]

Horkheimer to Karl August and Olga Wittfogel, 10/29/1935. In: MHGS Bd. 15 (1995), 418.

Herbert Marcuse Nachlass, categories: “1936,” “Zur Geschichte des Atheismus,” and “Lesebuch der materialistischen Lehren der abendländischen Philosophie von der Antike bis zum Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts.”

See above, “Excerpt: Horkheimer on Adriaan Koerbagh in “Authority and the Family” (1936).”

Horkheimer defines the category of ‘Authority’ as class domination as early as his 1936 “Authority and the Family” essay: “In all the forms of society which have developed out of the undifferentiated primitive communities of prehistory, either a few men dominate, as in relatively early and simple situations, or certain groups of men rule over the rest of the people, as in more developed forms of society. In other words, all these forms of society are marked by the superordination or subordination of classes. The majority of men have always worked under the leadership and command of a minority, and this dependence has always found expression in a more wretched kind of material existence for them. We have already pointed out that simple coercion alone does not maintain such a state of affairs and that men have learned to approve of it. Amid all the radical differences between human types from different periods of history, all have in common that their essential characteristics are determined by the power-relationships proper to society at any given time. People have for more than a hundred years abandoned the view that character is to be explained in terms of the completely isolated individual, and they now regard man as at every point a socialized being. But this also means that men's drives and passions, their characteristic dispositions and reaction-patterns are stamped by the power-relationships under which the social life-process unfolds at any time. The class system within which the individual's outward life runs its course is reflected not only in his mind, his ideas, his basic concepts and judgments, but also in his inmost life, in his preferences and desires. Authority is therefore a central category for history. The fact that it plays so decisive a part in the life of groups and individuals at all periods and in the most diverse areas of the world is due to the structure of human society up to the present time. Over the whole time-span embraced by historical writing, men have worked in more or less willing obedience to command and direction (apart from the extreme cases in which slaves in chains have been whipped into field and mine). Because the activity which kept society alive and in the accomplishment of which men were therefore molded occurred in submission to an external power, all relationships and patterns of reaction stood under the sign of authority.” In: Critical Theory (2002), 68-69. Translation modified.

Cf. Horkheimer and Adorno’s late 1940s reflections on ‘prehistory’ in their respective correspondences, such as those translated here:

From: “Über Lenins Materialismus und Empiriokritizismus (1928/29). MHGS Bd. 11 (Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, 1987), 175. Author’s translation.

Horkheimer, “The Authoritarian State” [1942], Translation by Peoples' Translation Service in Berkeley and Elliott Eisenberg. Telos Spring 1973, No. 15 (1973), 19.

“Memorandum Friedrich Pollock—Max Horkheimer. New York August 1935.” In: MHGS, Bd. 15 (1995), 380-. Author’s translation.