Revised Collection: Revolution and Rhetoric (1936/37)

Supplements and Notes for Horkheimer's "Egoism"-essay (1936)

Part of the series on Horkheimer’s 1930s Essais Matérialistes.

Table of Contents

Collection: Revolution and Rhetoric (1936/37)

I. Postscript: Editor’s Remark on Greer’s Book (1936)

II. Lecture: The Function of Speech in Modernity (October 1936)

III. Lectures: On Authority and Society (1936/37)

Postscript: Letters on Working Methods and Applications of the “Egoism”-essay (1936-)

Notes: Revolution and Rhetoric in the Essais Matérialistes

§1. The “Egoism”-Essay (1936): Program and Problematic

a) Cruelty (and the Terror)

b) Critique of Anthropology

§2. The Fate of the “Egoism”-essay: Speculation, Variation, and Self-critique

a) Speculative Annotations for a Theory of Rhetorics (1946)

b) Adornian Variations: Bourgeois Terrorism (1937/38-1952) and Negative Anthropology (1969)

c) The “Egoism”-essay: A Portrait of the Author as a Drowned Man

The third text in the following collection is a transcription of the English typescript of the lectures on “Society and Authority” (1936/37) from the digitized Horkheimer Nachlass through the former Stadt- und Universitätsbibliothek at Goethe University, Frankfurt a.M. The German typescript of the lectures was published in Max Horkheimer, Gesammelte Schriften. Band 12. (1985),1 under the editorial direction of Gunzelin Schmid Noerr, alongside the German typescript of the late 1936 ‘luncheon’-lecture on “The Function of Speech in Modernity,”2 which has been translated into English for the second text below. The first text is a translation of Horkheimer’s “Nachbemerkung zu Greers Buch” [Donald Greer’s The incidence of the terror during the French Revolution; a statistical interpretation (Harvard University Press, 1935)], published in the third issue of the fifth volume (fall/winter 1936) of the ZfS.3

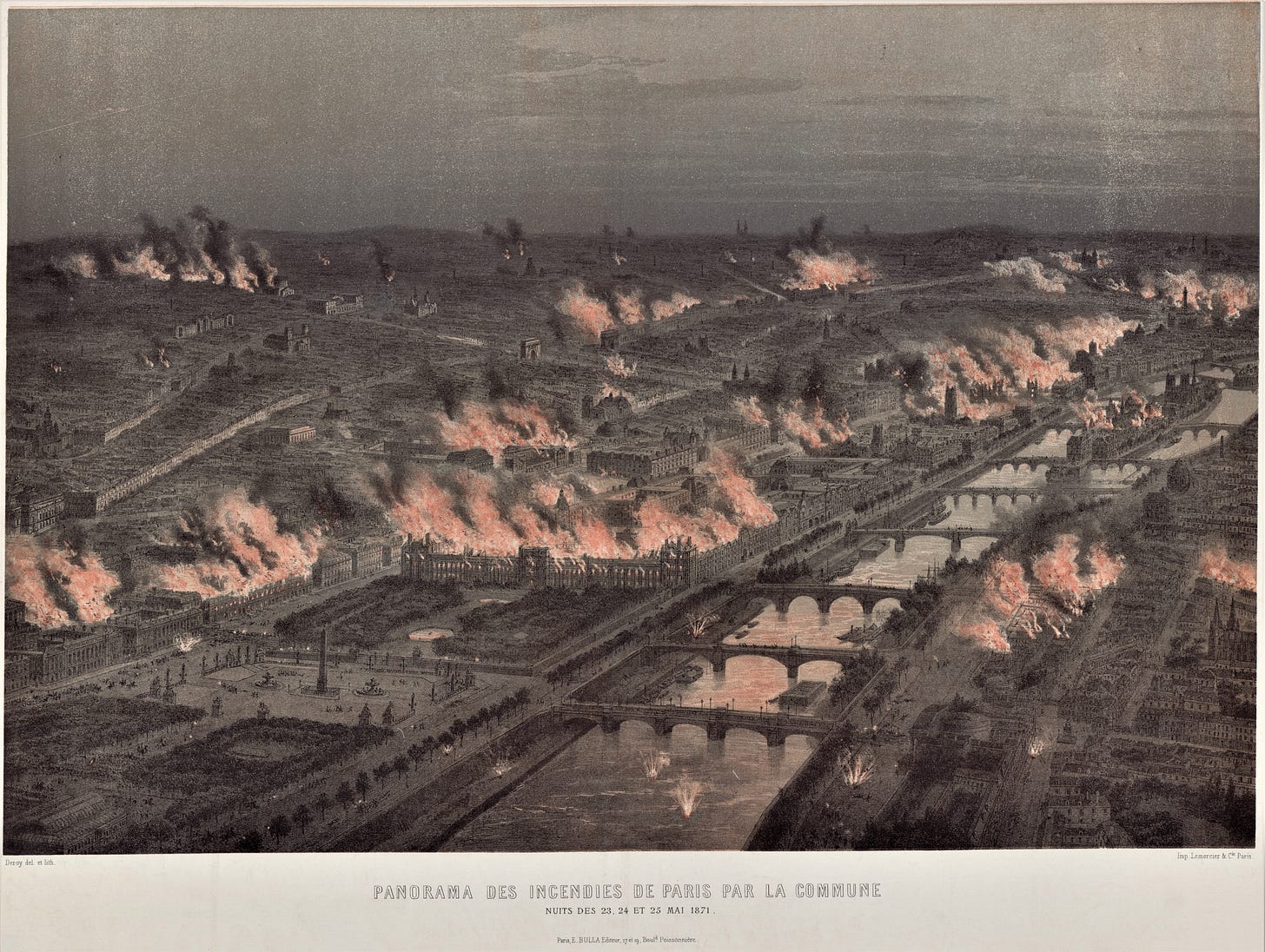

Two Elements of the French Revolution: Judged by what could actually have been accomplished at that moment, what makes the sympathetic observer feel ashamed is not that the French Revolution went too far, or that the implementation of its program only came about during a protracted period and after severe reverses. What does disturb him is the venting of what were precisely non-revolutionary, philistine, pedantic, sadistic instincts. As a practical matter, the revolution needed the support of segments of the petite bourgeoisie. But at the very beginning, the subaltern maliciousness of those strata made an ideology of the solidarity of the nation which the revolution invoked in theory. It is true, of course, that ideology contains impulses which not only point beyond feudal society but class society generally, but they are to be found in the writings of the “philosophes” rather than among the sadistic petite bourgeoisie which came to power for a time. Compared to them, it may indeed have seemed a salvation when the representatives of the developed forces of production, i.e., the bourgeoisie that was ready to take over, assumed leadership after the fall of Robespierre. The interpretation of the French Revolution by direct recourse to the philosophy of the Enlightenment distorts reality almost as much as does the insolence of a certain romanticism which only objected to the horror of the guillotine because it did not serve the Bourbons. In today's Germany, the two elements of the French Revolution, pedantic philistinism and revolution, appear as distinct historical powers. If they do it in the service of the dominant bourgeoisie, the petit bourgeois and the peasants may rebel and call for the henchman, but the forces directed toward the creation of a more humane world are now embodied in the theory and practice of smaller groups of the proletariat. They are not concerned with the guillotine but with freedom.

— Horkheimer, Dämmerung (1934)4

I. Horkheimer’s Postscript: Editor’s Remark on Greer’s Book (1936)

Donald Greer, The incidence of the terror during the French Revolution; a statistical interpretation. (Harvard University Press, 1935)5

Two social functions of terror can be distinguished. First: the deterrence of the enemy, which a governing body or militant group enacts in order to assert itself: the target is solely the adversary. Second: terror has, however, also been implemented through history when the danger to be avoided was less the strength of the enemy than the wavering attitude of one’s own followers. In the latter case, the target consists in one’s own following itself. Distinguishing which of the two kinds of terror any one determinate terroristic act should be assigned to is difficult for the historian. As a rule, both kinds of terror have a role to play in coordination with one another. This is particularly true of the French Revolution, to which Greer’s book refers. On the basis of the perspective developed in the essay on “Egoism and Freedom Movements” in this journal, however, certain theoretical criteria can be derived which may have significance for understanding this individual case.6

Modern freedom movements have in large part taken on a typical course. Propertyless masses, under the leadership of the bourgeoisie, took up arms against the antiquated conditions which originated in feudalism, only to be then integrated into the new social order themselves. This second phase of the movement, which was in most cases noticeable from the beginning, can be traced back to the fact that even in this new [social] order, the masses are forced into renunciation and come into conflict with the ruling bourgeois class strata. To the extent the interests of the propertied and the broader masses coincide, there are no particular grounds for terror in the second sense—that is, calculated for the movement’s following. The masses hope, not only on the level of consciousness but also on the level of their instincts, for a reversal of their fate; no particular measures are needed in order to compensate their disappointments by means of bloody spectacles. However gruesome the fight against the enemy, i.e., the powers of the past; as far as the bourgeois revolution might go in response to the as-a-rule inhuman acts of the opposing side, as it captures and executes the supporters of absolutism as far as its own sphere of power extends; as long as the fighting persists in full force, terror is essentially a matter of deterrence. However, insofar as the terror increases, even when the enemy has largely been repelled, it increasingly acquires the second, irrational kind of significance, and the conflict between the power of the propertied class strata which have risen to power, on the one hand, and the propertyless parts of their followership which have been forced into material deprivation, on the other, manifests itself. As the more radical elements of the populace come into open opposition against the victorious party, the sacrificial victims of the terror tend less and less to be members of the nobility or the clergy than of these radical groups themselves. At this juncture, the distinction between revolution and counter-revolution in the bourgeois era also tends to become blurred, as the terror increasingly begins to take on particularly cruel and degrading forms. It is only at this stage that major concessions are made to the nihilism of the petty-bourgeois masses.

Insofar as the hope is justified that a historical movement will realize happiness not only for a determinate social strata, but rather elevate the whole of society into that state in which all may enjoy all the goods of culture in equal measure, this movement lacks the most important drives towards terror of the second kind. The better part of the uprisings of the bourgeois epoch may well have allowed for a lack of clarity for a period of time concerning the quality of the state which they were supposed to achieve, but, in their progression, the violence of the social distinctions in the new order they sought became apparent. However, there were also groups which participated in each of these revolutions whose goal was not merely the ideal, but the real community of all individuals, and did so in increasing measure as the era progressed. As the groups which are oriented towards a solidaristic society no longer recognize the eternal necessity of impoverishment and the renunciation of drives, the introversion [Verinnerlichung] of material demands, and idealistic morality, they are also free of ressentiment, free of the subjective grounds from which the terror derives.7 They stand in another relation entirely towards political and criminal justice than the one to which the terror is so closely connected. One of the primary roots of cruelty is despair over the possibility of universal happiness. The groups which consciously seek to bring this about by virtue of their social existence, for all of their resolve and resistance, have no psychological need for the spectacle of blood and misery. The stronger the belief in the emancipation of humanity, the less the desire for sacrificial victims. As the right theory of society explains rational terror, it also protects against irrational terror, which has always, in all times, been the more terrible.

II. Lecture: The Function of Speech in Modernity (October 1936)

Prefatory Remark by the Editors of Horkheimer’s Gesammelte Schriften: Horkheimer gave this lecture, the German version of which is reproduced here, as a “luncheon” speech to American historians in mid-October 1936. He mentions it in a letter dated October 27, 1936 to the psychoanalyst Karl Landauer in the context of a discussion of Freud's concept of the death drive : [“In addition to the conception of the sorrow of those left behind that you mention, the satisfaction that flows from the thought that one's name will “live on” surely also belongs among the attempts to overcome death psychically. In this context, on the occasion of a lecture that I gave about ten days ago at a history club about the function of speech in modern times, I happened upon the great significance of names, which originates in very primitive habits of thought.”]8 The theme of the lecture is closely related to the essay “Egoism and Freedom Movements” that was written shortly beforehand. The function of the leader's speech is discussed there as a preliminary step in a further investigation into early bourgeois mass movements, in which egoism becomes visible as a foundational, but contradictory, feature of the modern image of humanity. In this lecture, Horkheimer expands on this aspect of speech. First, Horkheimer develops a historical contrast between the functions of speech in antiquity and the functions of speech at the outset of modernity. Then, he extends and sharpens this into the antithesis between the structural-argumentative and structural-internalizing functions of speech.9

Since the custom of giving scholarly speeches during meals is not as widespread in German academic life as it is here, I must confess this, at your friendly invitation, is my first scientific luncheon-speech. At first, I felt a little embarrassment over the question of finding a suitable theme. As you know, I am a philosopher, and philosophizing is a difficult business when one is feeling particularly carefree. Even then, there is the real danger that one’s listener will begin to yawn—if not outwardly, out of politeness, then at the very least in spirit. What sort of philosophizing could possibly take place at a luncheon! In the end, however, I thought to myself: this custom goes back to a venerable tradition. While the banquets of the Greeks had the advantage that one did not sit at the table, but rather laid down for the duration of the speech—so that the energies of the organism had freer play—the dinners of classical antiquity may have been considerably less digestible than a light American lunch. At the Symposium, Plato reports, the wine flowed freely, in veritable streams, and yet, as is well known, the philosophy of which they spoke placed no small demands on both speaker and listener. In thinking over the function of speech, inspired by your invitation, the thought occurred to me to make it the object of my address. I ask only that you consider the few reflections I am able to contribute on the theme at this time as, essentially, a stimulus to further thinking and not as a finished theory. The philosophical literature of antiquity recognizes, in essence, two different functions of speech: first, to facilitate the discovery of truth; second, to guide the listener towards a certain goal desired by the speaker, to influence the listener in practice. As you know, sophistic rhetoric did not recognize any objective truth whatsoever. According to the sophist rhetorician, that which appears the more plausible by means of skillful argumentation also appears to be true. Thus, it is not speech which depends on truth, but rather truth which depends on speech. Against this sophistic concept of speech, Plato defended the possibility of speech directed toward the true and the good in the Gorgias, elaborating further in the Phaedrus, and Aristotle explains in his Politics that the nature of the logos is “to point out what is useful and what is harmful, and thus also what is just and what is unjust.”10 The further classificatory divisions made between functions of speech which we find in antiquity are unable to change this foundational divorce. Cicero, who never tires of condemning eloquence in the service of subversive goals, does not advance beyond his Greek predecessors on this issue. On the one hand, speech in the exclusive service of truth; on the other, as a mere instrument of persuasion, regardless of whether the purpose is good or bad—this distinction dominates the classical debates concerning the function of speech. The practical application of speech, i.e., the influencing of others in political and private life, and especially in court (Aristotle speaks of advisory, juridical, and virtuosic speech, the last of which is only supposed to display the skill of the speaker), always either belongs more to the type propagated by Plato or to the type propagated by the sophists. In the purest form of sophistic speech, the logos serves as a mere instrument of some individual and egotistic endeavor; the purest expression of the Platonic idea of speech is the philosophical dialectic, i.e., cognition which unfolds in speech and counter-speech, in thesis and antithesis.

If we now turn to a consideration of speech in modern history on the grounds of this orientation in the literature of antiquity on rhetoric, a clear image seems to arise before us. Even in modern times, speech has played a role in the most diverse historical processes. There is hardly a single political event—whether those involving law-giving acts or law-giving legations, the founding of Reichs or their destruction, wars or revolutions—not marked by speeches or speakers of significance. Even if the method of historiography no longer consists, as in Thucydides or Livy, in allowing the persons involved speak for themselves, i.e., by quoting word for word the speeches they actually made or by the historian inventing a speech for them in accordance with their historical situation, such a historiography nevertheless does not appear so completely absurd, since speech has always been such an important historical factor. And, of course, speeches can also be distinguished according to whether they are made in service of personal power-seeking for individuals or small groups, or, on the contrary, the welfare of society as a whole, the general good; according to whether speeches were mere skillfulness in the service of private interests or of truth and justice; according to whether they belonged more to those of the Platonic or sophistic type. As you know, for example, the theory of history of the English and French enlightenment is closely connected with this problem. Thomas Hobbes was already of the conviction that, up to his own time, history had essentially been controlled by the cunning and deception of the priestly caste. For him, the task at hand was employing the same skillfulness in speech and writing in service of the good cause of absolutism.

For Hobbes, understanding speech as an instrument of domination is, to a great extent, the key to understanding historical events. Voltaire and his friends also believed that the lie of privileged groups essentially dominated the course of history until their time. This lie, they believed, must now be countered by truth, by reason; so far as it is, everything will turn out for the better. For the enlightenment, the logos is the strongest historical power. To the enlighteners, the whole of history appears as a contest between truth and lies, similar to how it appeared for the middle ages as a struggle between God and the devil. Some of you, however, will have come to feel in the course of your historical work that this—I would say: rationalistic—evaluation of speech in the historical process is not sufficient, particularly with regard to modern history. There is no doubt that, during the birth of the modern historical epoch, i.e., from the thirteenth through the sixteenth centuries, the spoken word was an important midwife. Since the time of the forceful oratory of Arnold von Brescin (towards the end of the twelfth century), innumerable lesser and greater spiritual speakers have arisen. In opposition to the rigid forms of the church, they satisfied the needs of the developing bourgeois class by speaking of Christian ideals in the language of the land and in widely understood expressions.

On the grounds of the increasing significance of trade and commercial enterprise, the intellectual needs of the bourgeois had also developed; they had come into material and spiritual opposition with the high-clergy and feudal nobility—in particular, initially, in cities in the south of France and the north of Italy. Religious tendencies in conflict with the church arose in part from sects and preaching mendicant monks, and in part from other tendencies which permeated Catholicism with the new bourgeois element and reconciled both powers. The Albigensians and Waldensians may be mentioned as examples of the first type, the Franciscans and Dominicans of the second. Now, of course, the Catholic Church, due to its vital significance for Italian and French politics, has been able to adapt itself to the new needs in these countries. With one hand, it made the various orders of preachers subservient to itself, and with the other, the Fourth Lateran Council expressly recognized that preaching on the whole had to be reshaped in any case. In another part of the Catholic world, however, the Protestant form of Christianity finally secured its footing, the form of whose worship essentially centered around the word. This return to the word of God and, further, preaching in the language of the land as the core of service to God are two decisive achievements of the Reformation.

If we now turn to those speakers who are so significant for modernity, to the preaching of mendicant monks and the sermons of the reformers, with the classical standards in hand, the inappropriateness of such a procedure becomes immediately apparent. In this modern speech, which is most closely connected with the development of the urban bourgeoisie, a certain property plays a role which in antiquity, if it was present at all, did not possess the same crucial significance. By this, I mean the function of speech which changes the listener himself—in his inner life, in his character. He should not only be convinced of some cause, but should “enter into himself”; he should better himself, become a different man, a new one. Instead of setting himself on pleasure and enjoyment, the man should be induced to keep his conscience pure, to lead a spotless life, to do his duty always and everywhere. He should not seek out the faults of others more than his own; he should never be satisfied with himself, but should always be concerned with the further purification of his person, with overcoming his natural drives and demands. We call this function of speech its “introverting quality”11 (in German: ihre verinnerlichende Funktion), or, to express it substantively: the “introversion,”12 die Verinnerlichung, it brings about.

This function has nothing whatever to do with the problem of truth and falsity. Regardless of whether the facts, religious or otherwise, invoked by the speaker are true or are not, whether the manner in which he paints an image of hell accords with the fundamental principles of classical logic or does not—as far as the goal is concerned, namely a transformation of the soul, none of this really comes into consideration. The speaker does not merely appeal to reason, his rational argumentation forms only the surface of his speech; rather, he appeals to the psyche, the unconscious, the drives. Even the orators of antiquity affected the affects of their listeners; indeed, the best among them even “played” on them. Cicero himself on occasion made fun of how he had instilled such fear and terror of the Catalinian conspiracy in his fellow citizens through his brazen exaggerations.

But for the orators of antiquity, the affects were only supposed to provide the lever to induce a determinate decision, to trigger a clearly outlined action; the addressees were not thereby supposed to spiritualize their wishes nor turn inwards away from outer matters; they were not thereby supposed to be transformed in their very essence. Wherever approaches of this kind are to be found in antiquity, one will also find similar social constellations to those which are generally characteristic of modern times. In modern times, there are two primary social tasks speech has fulfilled through its introverting function. These tasks are interwoven with, and cannot be separated from, one another in concrete cases. We will speak less of the first for now. It consists in the educational effect on those who belong to the bourgeois class themselves. The members of this social group were required to undergo a different kind of character-formation, be instilled with a different kind of virtues, than the type of human being characteristic of the Middle Ages. The latter type essentially met his social obligations by faithfully following all of the prescriptions in his predetermined sphere of life, performing his labor in the conventional manner, and ceding to the church or other lords whatever they demanded from him. When left to his own devices, he was able to let himself go to a certain degree, much like a child who has completed a certain required task. The modern human being, however, is always and everywhere responsible for themselves; the modern economy relies on everyone taking care of themselves. The businessmen and lords of the first manufactories could not just live hand-to-mouth, could not simply spend what they earned, but had to set their earnings aside to expand their businesses. They had to restrict themselves in service to enterprise. The suppression of drives, exclusive focus on acquisition, meticulous control over one’s own lifestyle and that of one’s family, and, above all else, thrift—these are the properties the prevailing type of human being of the present epoch were required to develop. This necessity largely dominates the ecclesiastical and cultural life of the era and gives ecclesiastical and even public speech in general its uniquely harsh and ascetic character. Speech has thus fulfilled a highly significant civilizational task. The ability of the human being to set aside his own drives and find satisfaction in his labor, profession, and working life is the precondition of the tremendous unfolding of science, technology, and industry in this epoch. The moralizing function of speech in this process can hardly be overstated.

But the effect on members of the propertied class strata forms only one side of the social significance of introversion. At the outset of the modern era, there arose the problem of incorporating large, propertyless masses into the new order of society. These masses consisted in part of discontented, impoverished, desperate peasants who could no longer eke out a living as a consequence of social transformations, in part of the growing propertyless class strata in the cities. The problem of managing such great masses has largely dominated history since the fourteenth century. The relation between these masses and the bourgeois class fluctuates. On the one hand, the misery of the masses was a visible expression of the obsolescence and incapacity of the feudal order, the abolition of which the businessmen and factory owners also had an interest in. On the other, the new economic order was also incapable of actually satisfying these masses. The poor had to learn how to set their wishes aside, to submit to factory regulations in particular and the demands of modern life in general—in short, to adapt as well as possible to the new conditions of life which were by no means easy to adapt to. Thus, we sometimes find the bourgeois class in league with the rebellious masses of the peasantry and the cities in an ever-renewed onslaught against feudal orders and privileges, against the nobility and the church, and at other times find the bourgeois class in opposition to these very same masses, putting them back in their place as their strict lord and master, teaching them the lesson that they are still far off from living in paradise. At high points in modern history—in the German Reformation, in the English and French Revolutions—this ambivalent relation appears clearly across the individual phases of these movements. But even in the more peaceful periods of modern history, each of the two sides can be distinguished from the other; they manifest together in politics, legislation, education, and cultural life as a whole.

The situation in which this influence—partly enlivening and inspiring, partly ascetic—is most pronounced is that of the speech of the leader at mass assemblies. Through this kind of speech, people are supposed to be filled by the nothingness of their own person instead of by their own person. The individual is supposed to set aside his immediate interests and goals for the sake of higher goals, which are represented by the leader—in fact, incarnated by him. Introversion is accomplished indirectly through love of the leader. The leader is the mediator between the decisive groups of society and the masses, and the relation between these groups and the masses fluctuates; since these groups cannot fulfill the all of the needs of the masses but are nevertheless in need of them, everything depends on the blind obedience of the masses towards the leader, on their relating to him as dutiful children submit to their admired father. The speech, however, is the most important means for establishing, strengthening, and renewing this relation. Leaders in modern times have therefore in large part been mass orators. Here, we immediately find an important distinction between speech essentially aimed at rational conviction and speech essentially aimed at introversion. Wherever cognition, clarity, and actual conviction are of utmost importance, a smaller circle of listeners is preferable to a larger one. An academic seminar about a difficult theme tends to be the more fruitful the fewer participants there are. Parliaments also tend to form smaller committees to address important questions. On the other hand, wherever the aim is not so much the understanding of the listener as much as it is the listener being crushed, that he suppresses his own person and interests and finds full satisfaction in devotion to the figure of the speaker and the goals the speaker represents, the attendance of entire masses is preferable. A whole series of externalities—the solemnity of the space, the time of day, the songs before and after the speech, the ceremonious conduct of the speaker—play an important role. For the organizers of the event, the speech is not understood as a sober presentation, an analysis of actual social relations, but as a psychophysical influence, a medical treatment, a healing cure. This is already apparent from the frequency of their assemblies and the obligatory character of attendance at each of them; people are commanded to be present, and sometimes even detained for such purpose.

The ordinances from the Reformation period are very eloquent in this regard. Anyone who misses the sermon without prior excuse is punished with a fine, an iron collar, or imprisonment. The person of the speaker does not recede into the background, as in the case of a purely argumentative speech, but is clearly foregrounded; the place from which he speaks (given the mass of participants) must be elevated; the speaker himself, as well as some of his words, acquire an invulnerable, magical character. The attendees, who are supposed to surrender their own wishes and, in some circumstances, their own lives, cling to these symbols, by means of which they transcend themselves and their own smallness; such symbols are the guarantors of eternity. I cannot elaborate this psychological mechanism in detail here, but I hope I have succeeded in indicating the peculiarity of the kind of speech I have in mind. The whole question is closely linked to the problem of the leader in modern history. If, at the outset of the modern era, the venue for the leader’s speech was essentially the church, and its content was just as political as it was religious, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the stage for the effect of the leader on the masses was the political mass assembly. Here too, however, I would warn against judging historical phenomena one-sidedly on the basis of the present. Certainly the speaking events in some authoritarian states in Europe, those which have been calculated to have a purely suggestive effect, appear to us a procedure no longer appropriate today. These present-day appearances do not mark the beginning of modern Europe, but its end: they are latter-day repetitions. In earlier centuries, mass assemblies and mass influencing in general played a highly significant and progressive role in the development of humanity.

The incorporation of the masses into the given social order, their binding to the goals of the bourgeoisie—the hard school of modern social life first made the elements of these masses into self-conscious individuals. Without the work of its religious and political leaders and their oratorical influence on the constitution of the masses, modern history is inconceivable. Arnold of Brescia and Savonarola, Bernard of Clairvaux and Francis, Luther and Calvin, Cromwell and Danton are just a few of the more prominent names, and some of them would not even describe themselves as great orators. But these leaders had their sub-leaders and sub-sub-leaders, a whole staff of speakers, and all of them used speech as a tool to educate the masses, through love and admiration of the supreme leader, for the sake of the introversion and deployment of their person for determinate social goals.

The language in these speeches faithfully mirrors the social situation. Since the masses are supposed to help in the struggle against the old cultural forms, the cry for freedom permeates modern speech. Honor and freedom are its grandest motifs. The leader himself appears as the rebel opposed to the authorities which are to be overthrown. On the other hand, however, only individual, determinate authorities are to be overthrown, and by no means is any autonomous and independent spirit to arise within the masses. Thus, for example, Savonarola attacks the pope of his time in the most violent manner, but by referring himself to earlier popes; he rejects the church of his time, but by referring to the authentic and true church. An even earlier political leader, Cola di Rienzo, who already bears many properties of leaders of the modern type, wanted to change the social relations of Rome in his time and thereby to renew the splendor of ancient Rome. The Reformation itself enters the battlefield against the Catholic Church brandishing the original, authentic Christianity. The leader declares himself in the course of his speech a liberator on the one hand and an executor of the ancient, holy powers and forces on the other; he always feels himself to be a messenger from a higher power to whom he is obedient in the same way his sub-leaders and followers are supposed to be obedient to him. All too easily, his speech can pivot from an encouraging, inspiring tone into an admonishing, even scolding and contemptuous one. There is something inherently misanthropic to many modern leaders. There are speeches from the Reformation period in which the speaker addresses his listeners as devils or breaks out into the cry: “May plague, war, and hunger come upon you.”13 Luther himself spoke the following: “In secret, burghers and peasants, men and women, children and servants, princes, officials, and their subjects are all of the devil.”14 But such contempt for the masses, which is found among many of the more modern leaders of the present, does not harm their popularity in the least.

Whenever the crowd attends a speech in which they themselves are scolded, they must have the feeling there are other people and groups somewhere out there which are more despised by the leader, and even completely rebuked by him. In the Reformation, Catholics played this role; in the French Revolution, aristocrats. The crowd feels relatively loved by the leader and, as it were, compensated for the renunciation of their drives, because at the very least he still speaks to them, but for those on the outside he has only damnation left over. I have already mentioned the symbolic significance of individual words. In addition to this, I would like to point out a further peculiarity of mass-speech in modern times, so far as these speeches aim not so much at the formation of judgment as irrational influence. This is evident in the repetition of individual words or individual sentences in a stereotypical form. Savonarola once said that the preacher does not need the gift of miracles, but only the frequent repetition of the word.15 At a first glance, it may seem this repetition has the purpose of ensuring certain facts are not forgotten. However, this would be a superficial perspective on the matter, which is evident from the fact that it is less important that one points out the facts than that one always uses the same signs and words—in the manner of a ritual. It is not the content, but the form that is essential. Words and signs become independent entities, so to speak; they appear to be endowed with a power of their own. This attitude towards words points back to earlier stages of human history. Through anthropology and ethnology, we learn that many primitive tribes believe a person’s name has an existence of its own, indeed that it is the soul of the one who bears it: for example, in the belief that by digging someone’s name into the earth and then crossing it out or erasing it, one has thereby inflicted something terrible upon its bearer.

The name possesses a significance akin to that of a weapon, or the image of a person. The utterance of a name or of certain words in general has at certain times a healing, at other times a fatal significance. Think of the prohibition on uttering the name of God in the Jewish religion. Even in the consciousness of modern times, we find remnants of this attitude. Thus the German saying that one should not “den Teufel nicht an die Wand malen,” which means that uttering the name of the devil will attract the devil himself, and in a broader sense that that misfortune strikes if one calls it by name. In another respect, the reassurance modern man feels at the notion that “his name lives on” after his death is also connected with these ancient psychic reactions. Though only a part of this attitude still remains in conscious life, we know from modern psychology that such ancient inclinations of the human race live on in the unconscious, or rather, that the logic of the unconscious psychic life of modern human beings has close affinity with the thinking and feeling of primitives. And the mass speaker who is concerned with overwhelming the listener appeals precisely to this unconscious, to the deepest and most hidden instincts of the crowd. He ensures that when certain words and sentences are spoken, a “holy shudder” of enthusiasm or a wave of hatred arises; that aggressiveness is evoked with one word, a feeling of guilt with another; that, depending on the word, contrition or rapture kicks in. He hands the crowd words which they brandish against evil, to banish any danger, like a crucifix or holy icon. On the other hand, he creates words which are inseparably bound to the concept of something bad and depraved, so that whoever is called by such a word is from then on branded with an indelible mark of shame, no matter what else he may be.

The better part of the technique of modern speech is based on the correct manipulation of repetition, and here its far-reaching commonality with advertising and propaganda becomes apparent. It would lead us too far off course to uncover the psychological mechanisms underlying the political as much as the commercial propaganda through the last four centuries. In any event, I believe I have been able to indicate to you a crucial distinction between speech for the sake of conviction and speech for the sake of introversion. In the speech which aims to enable the formation of judgment—regardless of whether the judgment that the speaker tries to prove is true or false—it would be extremely clumsy if the speaker were to use the exact same words over and over again, and to repeat the same sentences. The speaker has to be on guard against the accusation of stereotypy, he must take care not to detract from the liveliness of the talk with formulaic phrases, and not say the same too often—or, at least, not in the exact same words. In modern mass speeches, it is just the reverse.

Though the great speakers and leaders of modern times have not always been conscious of these facts in detail, many have nevertheless grasped the fundamentals. A great German preacher from the transition between the thirteenth and fourteenth century formulated the fact of introversion clearly: “Thus, all pious exercises were invented—be it prayer, reading, singing, keeping vigil, fasting, penance, and whatever else there may be—so that man might be kept from alien, ungodly things by them.”16 Political speakers demand the renunciation of the claims of the individual not so much with a view to God and eternity as to people and race, for which they also assert a kind of eternity. They have been extraordinarily clear about the presupposition, significance, and technique. As one contemporary orator says: “False concepts and bad knowledge can be eliminated through learning, resistance of feeling never. Only an appeal to these mysterious forces” (he is thinking of instincts, of the unconscious) “can be effective here; and this the writer can hardly do, but almost always only by the speaker.”17 There are considerations to be made concerning the best time for the speech, and it is expressly declared that evening is most suited for generating the desired mood, since during the day “the volitional forces of men seems to resist with greatest energy the attempted imposition of a foreign will and foreign opinion.”18 Whereas the speaker concerned with knowledge and reason, indeed with intellectual attention in general, wants his listeners to be as awake and as lucid as possible, it is expressly said by the mass speakers that it is better the masses are not “in full possession of their intellectual and volitional vitality”19 when the speaker addresses them. I could pile such testimonies from speakers and leaders over the last few centuries on top of one another. When you look through the documents yourselves, you will find them to be full of such evidence.

By way of conclusion, I would like to return to an objection which you, as historians, have surely already made inwardly and toward which I have even alluded on occasion. It is the question of whether speech in antiquity did not also bear the peculiarity spoken of here. To this, I answer that here, the problem is similar to many in the theory of history: a phenomenon which stands out particularly strongly in a certain historical period can already be observed earlier as an element of earlier historical events, but the weight it has is different. Certainly, there are many speeches to be found in antiquity which bear features similar to those I have highlighted. Ancient Rome knew similar social contradictions to those which predominate in modern times—namely, the contradiction between patrician and plebeian. However, there is still a significant distinction.20 The class strata which performed the most difficult labor in the Roman Empire were the slaves. They did not need to be adapted to the social process through a reformation of their character as did the masses of the fourteenth, fifteenth, and following centuries. They were not free, but compelled by physical means of violence. Their opinion, their own will played much less of a role. The speech to the masses is a social function that plays out between those who are free, not between masters and slaves. In the domination of slaves, the cross performs its real function as an instrument of torture and not as a symbol. Meneius Agrippa speaks to the masses.21 But his speech is addressed to the plebeians, not to the slaves. Beyond that, despite some affinities with more recent speeches, which arose from affinities in the situation, it has a rather rationalistic coloring and has little to do with introversion. Menenius seeks to prevent the plebeians from rebelling against the patricians.

But his parable of the stomach and the other parts of the organism is meant to make clear that it is wiser and more useful for them to submit, not, however, that they should abandon themselves. Further: the distinction we have drawn between modern and classical speech is contained within speech in the present as well. Even today, some speeches appeal more to reason and others aim more for introversion; indeed, every single speech bears both features, only in varying proportion to one another. Where in the authoritarian states of Europe, we observe the whole apparatus of mysticism and suggestion predominate in the speech of the leader, in democratic states the speaker has to appeal more to the understanding and interests of his listeners. The latter leaves it to the listeners to form a final judgment themselves, and gives them time to think over the individual arguments in silence, and decide independently. The listener should not be persuaded, but instructed and enlightened, which requires reflection and examination of their own. I hope I have stimulated as much with my own comments today.

III. Lectures on Authority and Society (1936/37)

[Prefatory Remarks by the Editors, MHGS, Bd. 12 (1985):] Horkheimer’s three lectures on ‘Authority and Society’ constitute the beginning and end of the ISR’s first lecture series at Columbia University in New York. This series of lectures was announced [in late 1936] for the first semester of 1937 under the title ‘Authority and Status in Modern Society.’ This theme was pursued further in several lecture series; however, only the first has been preserved in the Horkheimer-Archiv. In addition to Horkheimer, Herbert Marcuse, Paul Lazarsfeld, Friedrich Pollock, Julian Gumperz, Erich Fromm, Franz L. Neumann, Leo Löwenthal and Ernst Schachtel—whose lecture, however, was cancelled—were listed as contributors to the lecture series. Horkheimer summarizes the content of their individual contributions in his closing lecture. This sequence of lectures immediately followed the publication of the Studien über Autorität und Familie, begun in Europe [prior to the ISR’s exile] and published in Paris [by Librairie Félix Alcan] in 1936. Horkheimer’s lectures are an introduction to the problematic developed in detail in the Studien: the centrality of ‘authority’ as a social-theoretical category. Beyond this, these lectures contain an outline of the social-philosophical method representative of the ISR, [defined] against the background of its oppositions to both the rationalist-empiricist and metaphysical traditions of [social] thought.22

[Transcribed from English typescripts in the Max Horkheimer Archive (MHA), [Na 1 651]]

A. First Lecture

The courses on Authority and Society to be given during this and the following semester by members of the Institute for Social Research including myself depart in many respects from usual procedure.

The delivery of our lectures will suffer in the main from one defect which no one can feel more keenly than myself, namely, the linguistic difficulties. It is not such things as a grammatical error, the misuse of a word, or, perhaps, the foreign accent which we ourselves shall feel in these hours as impediments—your indulgence can at least partly compensate us in this regard; it is rather our paucity of words and our deficiency in delicate shades of expression. The difficult subject makes it desirable to employ the whole wealth of nicely turned phrases and balanced constructions which the English language places at the command of the skilled. But many of us must be content to have on our lips only the simplest, the every-day phrase. This imperfection is less palpable in imparting isolated facts. It manifests itself strongly, however, in the development of abstract principles and then the linguistic form does not fit the idea like a form-fitting gown, but rather like a cowl of coarse texture that misfits the body. It would be a grave mistake to presume that this flaw can be overcome easily. I can promise you, however, that we shall do everything to offset this deficiency by other means.

The second peculiarity of our lecture is again a matter of whether we are talking the same language, but in a figurative sense. Most of us have received our intellectual training not only through the medium of the German language, but also in the German scientific tradition. With regard to our subject, it may be useful to add a few words concerning the special and distinctive characteristics of this tradition. England and France played important roles in the world economy long before Germany. Commerce and industry developed in Germany only after the middle classes of other countries had begun to exercise not only economic power but also political power and had stamped their mentality upon the cultural life of these countries. During the French revolution, and more so during the English revolution, the Germans engaged in industry led a modest and relatively submissive existence both as individuals and as a social stratum. Their entire mode of living and thinking was not directed toward seizure of the internal political power, the administration of the state or the expansion of national dominion over maritime routes and foreign continents, but toward a contemplative, introverted life. Absolutism, allied with the feudal powers, did not leave them any other outlet. Their gradually increasing energies turned instead upon themselves, upon the depth and range of ideas, ignoring, however, their applicability.

We do not have to discuss the detrimental consequences of this development. They are well known to you. While there came into being in England and France a self-conscious, world-wise middle class able to take care of its affairs, the corresponding German strata became accustomed to transacting their business under the continued guidance of a bureaucracy almost free from their control. Such qualities as reverie, fanciful imagination, romantic tendency, the inferiority complex of the individual, subordination to leadership, yearning for the privilege to obey, the whole bent for irrationalism, are characteristic of the German people, a fact which recent events have revealed clearly enough. These traditional traits manifest themselves conspicuously both in their thought and speech. French literary composition and English composition distinguish themselves still more by simplicity, preciseness, lucidity, and clearness of arrangement. These qualities have been acquired by working with nature, by handling and molding men and things and by having command over them. The Germans, driven to introversion, have developed ideas not so much to put them to use, but rather to play with their theoretical possibilities, always mirroring the general in the particular. Their judgments are often involved and only indirectly related to definite, tangible objects of reality. The same concept fulfills different functions depending upon its position in diverse trains of thought. Only the context reveals the function referred to. The idea of a sentence cannot be understood solely by what precedes it but requires even more the further reading of what follows; briefly, thinking is much less directly related to the actual Here and Now than it is in the positivist mode of thinking of Western Europe. And so German metaphysics has become synonymous with obscure, complicated, and ponderous thinking good for—one never knows what.

While we do not overlook the drawbacks inherent in such a development, the much complained-of obscurity of this mode of thinking is the price paid for certain qualities which cannot be attributed in the same measure to French and English literature. Descartes’ Meditations and David Hume’s Enquiry are works of French and English philosophy, justly famous for their exemplary lucidity. Anyone reading these writings, not so much to broaden his education or, perhaps, to pass an academic examination, but as these authors expect him to, in order to gain knowledge concerning the human mind and its relationship to the outer world, will make an amazing discovery, provided, of course, that he approaches the subject with all seriousness. The stream of thought, the individual concepts, the judgments and conclusions, apparently so pellucid, prove to be loaded with innumerable unsolved problems which never strike the attention of the superficial reader but present themselves only as one proceeds from words to actual conditions. These methods and opinions developed by these writers reveal a remarkable impotence when confronted with the concrete manifestations of the human mind, of the individual psyche as well as of configurations of societal life, the different forms of culture, the economy, the organization of states, education, religion, art, etc. When these simple thoughts are applied to the problems of the living world and one is no longer satisfied to study this or that recurrent fact in isolation, but endeavors to comprehend tendencies and the general nexus of things, it becomes manifest that this formal clarity of thinking falsely appears to indicate clarity concerning concrete objects.

The difference between this way of thinking, particularly adapted to the technique of the natural sciences and the presentation of historical facts in the Central-European tradition, lies in this. We do not maintain that we are able at the outset to formulate principles which give a definite insight into the very essence of things. We do not claim to have at our disposal such simple definitions that any further treatment of the subject would merely be in the way of differentiation, application or amendment. If this were true, I should only have to give in my next lectures definitions of authority, of society, the family, etc., later to illustrate these definitions by means of specific cases and to show their interrelation, and on your part you could look forward, after a few lectures, to taking home definite insights and preserving the finished product forever after. We are of the opinion, however, that clarity comes at the end, not at the beginning. In the beginning, naturally, we must make use of abstract definitions, but such definitions, when tested by reality, always remain isolated notions, distorted and untrue. Such untrue statements, which are necessary in all abstract definitions, are overcome only by slow and progressive proximity to concrete objects and by keeping a watchful eye for the essential. This difficulty is at the same time an advantage of the philosophical method which we will follow in our lectures.

Whenever I mention that I am studying the role which authority plays in present-day society, my interested friend will ask questions such as these: “Well, what do you think of authority anyway? What do you think of democracy and fascism? Shall children be brought up without restraint? Is this society heading toward a catastrophe?” and similar trifles which people expect me to dispose in passing. At the risk of being taken for a metaphysician hopelessly enmeshed in cobwebs of obfuscation, I usually answer that if we wanted to arrive at an understanding of the problems, both of us would have to labor hard. As a rule, my astonished friend is then polite enough to suppress the remark: “Why, you have been studying these problems for years, and now you cannot even answer such simple questions.”

Even at the conclusion of these lectures you will not have a definite formulation of the problem. You will possess only the equipment by which science enables you to analyze the functions of authority in modern society. In every case which you wish to analyze, you must adjust these tools anew to the given historical situation. The science of history does not save one the trouble of thinking—rather, it stimulates thinking, although of another sort than that required by the formal sciences. During our lectures we shall endeavor to convey to you as complete a picture as possible of the role of authority in the life of modern society. You must bear in mind, however, that this picture does not consist in a mere succession of facts. You will see that the correct understanding of every fact brought before you must be founded on theories which will be developed as we go along in our lectures. I must also warn you that we cannot give you a ready-made formula for the application of these theories to actualities since the latter are constantly changing. —So you see that the assimilation of the views which will be presented to you here is beset with a number of specific difficulties.

After having shown you all the obstacles arising from our foreign origin and our particular methods, as well as from the subject we are dealing with, I shall now delineate the procedure by which we shall seek to overcome these obstacles. You may find that this procedure, too, is somewhat unusual. —The problem of the function of credit in our economic system, the significance of sovereignty in constitutional law, the role of general concepts in epistemology, and many other problems are established subjects of scientific literature and of university lectures. On the other hand, the problem of authority in modern society, to the study of which we have devoted our efforts for several years, has no precedent in the field of scientific investigation, for it owes its origin to a newly-awakened interest in current history. In order to understand the present we must go back to the past, not for its own sake, to be sure, but for reasons which have to do with the practical tasks of the day. A few years ago our problem, which arose from the concern for contemporary history, would not have been recognized as such even by the scientifically trained. Since then it has been acknowledged as one of the most urgent theoretical problems of the present time. The complete reversal of the former attitude is reflected by a series of important publications on these subjects, no less than by the speeches delivered on the occasion of the Harvard Tercentenary. The role of authority in modern society has become one of the basic problems which the foremost scholars of the world have made the subject of their concentrated studies.

You will be disappointed if, for an elucidation of our problem, you look into the existing scientific literature, where one may readily find definite answers to questions concerning the functions of gravitation in our solar system, the circulation of the blood in the human body, or the effect of a certain bacillus on organisms. Even if books do not give the desired answer there is probably always some scientist to whom one may turn for information. On the subject of authority, we find occasional references in historical works, in text books on psychology and sociology, but above all, in the speeches and programs of statesmen. Now, quite apart from the fact that these references approach the problem from various angles and of necessity bear the stamp of superficiality because they deal with matters only loosely connected to the essence of authority, they have also the disadvantage of contradiction and mutual exclusiveness. The most disturbing factor in the study of our problem, however, is the fact that the subject matter is scattered among various more or less unrelated fields. History tells us that this or that great man had this or that view on authority; sociology, that authority in the Middle Ages was regarded in a different light than it is today; psychology, that the attitude toward authority has its roots in the family; comparative political science, in what respect democracies, from antiquity down to the present, have been clashing with authoritarian forms of government. Then again, a statesman will declare that authority is the foundation of civilization and culture, while certain philosophers, mystics, or poets, like Tolstoy, proclaim that God is the only true authority and that over-expanding secular authority is the source of all evil among mankind. The fact remains that not only in Europe but all over the world there is taking place a social struggle, filled with individual tragedies, under the banners of authority, the authoritarian state, training for authority, the authoritarian personality, etc., although the majority of the people affected—and that includes the intellectuals—do not have a very clear view of these subjects.

If I have said that our knowledge of the essence of authority must be gathered in many fields of intellectual endeavor, I do not mean to imply that in the treatment of our problem we must disregard the individual insights of the various scientific disciplines. To solve the chief problems of the theory of society in a vacuum or in the rarefied atmosphere of philosophy, or neglecting the results of the meritorious empirical work of the individual disciplines, would set us back instead of helping us advance. It is true that specialization has often borne bad fruits. But this is not directly due to the differentiation of empirical thought. What has been lacking—and this should have been done before, in view of theoretical and practical interest in the great historical tasks—is the concentrated effort to relate the product of the investigations undertaken by the various sciences to the key problems of the present time. Philosophy, the universal, all-embracing science, is exposed to the same danger as the so-called individual disciplines; like these, philosophy is not built up with reference to the important problems of the times, which are in a continuous state of evolution and transformation, and is therefore not readjusted to them as the need arises. In attacking our problem we shall of course remain mindful of our purpose and avoid getting lost in the jungle of psychological, sociological, and juridical sub-questions and sub-sub-questions, nor shall we stop with the preliminary and preliminary to preliminary questions involving principles and methods. You are going to hear exponents of the individual disciplines: economists, psychologists, statisticians, historians, etc. They will speak about their own fields like most specialists who do not deviate from the methods of their own disciplines. There will be a difference, however, in this respect. While each expert separately will speak about his particular field, their joint effort will be coordinated and directed toward the same problem, namely, the significance of authority in the life of modern society.

I know that by now you have a number of questions in your minds. For instance: what is meant by authority in this connection? Is it authority in the meaning of authoritative institutions, such as the states, the constitution, the administration of the city, the police, etc.? Is authority considered a phenomenon of consciousness of a character trait? Does the term authority designate the quality of an impressive personality, such as a so-called leader, or does it designate a relationship between individuals? A little later I shall attempt to make some conceptual differentiations so that we may have a temporary starting point. Complete clearness, however, will come to you gradually only as we proceed in this course, that is, when you begin to perceive the deeper interrelations among these problems. The answers to such fundamental questions as have been outlined here must be deferred for a little while. In the course of the lectures, when a greater wealth of material will be at our disposal, we shall revert to these questions frequently and we shall then be able to deal with them more fruitfully than could be done at present. Right now I may tell you only that we shall consider authority as a phenomenon of consciousness, as a relationship between individuals, as a function of the family and the state, and in many other aspects, such as the interrelationship of family and state authority. Manifold as may be the working methods and the materials we shall present here, the discerning among you will soon become aware that everything is bearing on one question only: the mechanisms and the tendencies of the historical development of the present era viewed as a historical entity. We believe that in order to understand these a full comprehension of the category of authority is of considerable importance.

B. Second Lecture

In my introduction, I told you we shall not advance any definitions at the beginning of our discussions. Nevertheless, as we need a working basis, we cannot entirely do so without a number of conceptual differentiations of a general order, which will guide us throughout the whole course.

The concept of authority stands in opposition to two other concepts. Firstly, to that of free, self-directed action, or autonomy. In following my own, spontaneous judgment and not that of an extraneous power, that is, when my action is the clear expression of my will—of an autonomous will, we might say—I am not following the command of an authority. The preoccupation with the significance of authority as the antithesis of autonomy or, in other words, freedom and reason, has dominated the intellectual life of the last centuries.

You know that during the Middle Ages every individual in the Christian Occident was subjected to the supreme authority of the Catholic Church in all phases of his thinking and with his whole soul. Not revelation or God, but the Church had jurisdiction in all vital questions of human life. St. Augustine himself once said that he would not believe even in the Gospel if it were not supported by the authority of the Catholic Church. The dependence of men on authority, which is expressed in all social relationships of the Middle Ages, especially in the relation of feudal lord to serf, is also reflected by all phases of medieval cultural life. And since very detail of the earthly existence of the medieval man was regulated by this conscious dependence on higher authorities—the peasant, bound to the soul, looking to his lord, and the city craftsman to his princely patron and protector—it is not hard to understand why even an idea would not be regarded true unless it was upheld by an established authority. When a subject lay outside the province of the Church, support was sought in appeal to the authority of Aristotle or Plato, and to other classical authors. Even the authors issuing from the burgher class, which increased its power with the rise of the free cities and has impressed its stamp on cultural life ever since the Renaissance, could not dispose completely with the authority of older writings. We have seen this especially during the Reformation. The authors of that period did not oppose the Catholic Church with a new theory, but only with the literal text of the Bible. Hobbes, who was an atheist and materialist, and even Spinoza, frequently marshaled the Gospel or the Old Testament in support of their views.

The standard under which the modern era has led the charge against the Middle Ages, is Reason, the rational thinking of the individual, untrammeled by interference from any extraneous authority or power. This type of reason creates autonomy, the freedom of action of the individual. Time and again, all through the great literature of the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, time and again we find passionate attacks on the inward unfreedom of the individual. This unfreedom is not merely the uncritical acceptance of foreign opinions but also enslavement to one’s own desires and habits. Just as the individual in society has freed himself from the shackles of slavery or serfdom, he should throw off his inward fetters and begin to think independently. A German philosopher has said that Enlightenment is the intellectual coming-of-age of men. There is no name too great or exalted that a judgment supported by its authority should be accepted without subjecting this judgment to the critique of our reason. The type of authority described here is something negative: it is the antithesis of independence and freedom.

Upon hearing this statement someone will make the obvious objection that, after all, there is still something like desirable authority: naturally, it is not contrary to sound reason, and certainly it is in harmony with it, when a child follows the judgment of his father, a patient the instructions of the physician, or when the passenger aboard a ship places his implicit trust in the seamanship of the captain commanding it. If we did not have this kind of authority to rely upon, our lives would indeed be unproductive and we should perish before long. But remember: in the above statement we did not reject authority as such. What we reject is its authority untested by reason, for this authority is the root of heteronomy, the domination of others. When I have convinced myself, by virtue of my reasoned judgment, that another man knows more than I about a certain subject, and act accordingly, I do not consider him an authority in the same sense in which the Middle Ages looked at the Holy Scripture and the Church. We cannot rationally explain the superiority of a prophet in matters pertaining to God and to salvation, as we can the professional knowledge of a physician in matters pertaining to medicine. The physician has acquired this knowledge in a manner which is open to our rational understanding and therefore also accessible to our rational judgment. On the other hand, it is of the very nature of the prophet that his mission has been communicated to him through inspiration or grace, both mediums which elude rational control. Therein lies the difference between the two kinds of authority. I may mention now that, like the authority of the prophet, the authority of the so-called leaders in Europe, whom millions are blindly obeying at present, is of a mystic, irrational quality which is founded in the emotions of the masses.

The terminology used in our lectures carries out the distinction between the types of authority. Whenever the term “authority” is used without any qualifications, the lecturer means nothing else but the problem of authority and refers to the emotional and irrational type of authority which has no foundation in reason. Whether the subject discussed regards the relationship among persons, the character of an institution, or individual character traits, this is the type of authority which the great authors of the last centuries have designated as the antithesis of autonomy. In no way does this term imply any judgment regarding the desirability or undesirability of submission to authority in some situations. An excellent example of this type of authority is given by a woman who blindly submits all her actions to the will of a man because she loves him. This woman may find happiness or unhappiness in her submission to this man, but that will depend entirely upon the particular circumstances of the case and even more so on the qualities of the man. Happy or unhappy, one thing is certain: she does not act independently, autonomously.

Our problem is therefore concerned with the social implications of authority as heteronomy. On the other hand, in referring to authority founded in reason, we shall always qualify the term “authority”. We shall then speak of rational authority, that is, rational subordination and discipline, or, more often, in order to stress the opposition to emotional authority, we shall use the German term “Sach-Autorität,” which describes rational authority in its aspect of objective and consciously admitted superiority, complied with for practical reasons.

After having contrasted authority with independent action, or autonomy, we shall now proceed to compare authority with coercion. Authority does not enter into the condition of the Roman agricultural slave who, on the way to the fields and when driven back again to his miserable quarters, was kept in chains. This is an illustration of coercion, for the performance of the slave’s labor is not the result of subordination to authority. Of course, we do not wish to imply that authority is entirely free from coercion. What distinguishes the two is the fact that in authority, coercion is less direct and, above all, not physical. If the individual in Germany or in Italy recognizes the authority of his immediate superiors, and ultimately that of the national leader, it is not unreasonable to assume that the virtual omnipotence of the state bureaucracy and the threat of serious inconveniences if another attitude were exhibited, are not wholly inconsequential considerations. In the spontaneous respect of the labor an element of coercion is also present, although the individual is not always conscious of it. The feeling of this potential coercion, however, has been so completely incorporated in his psychological make-up that the awareness of coercion need not necessarily become effective. Elements of coercion underlie many phenomena of social life, for instance, our yielding to conventions, we are all mindful of the harmful consequences incurred by disregard of the customs of the milieu in which we live. In accepting the social order, laws, and customs, or obeying an exalted person invested with power, the individual is submitting to authority. In doing this, his action is not based entirely on reason or entirely on coercion. In the case referred to, the awareness of the high position of the feared personality has become part and parcel of the individual’s will; his fear is now enhanced by recognition and admiration. We all adjust our actions to the unconscious influence of innumerable ideas, habits, people and institutions. During the greater part of our lives we follow, without any visible coercion, the path marked out by the existing order. Our whole life is permeated by the influence of authorities. Observe yourselves, and you will discover that, on most occasions, your actions are based neither on coercion nor on your own deep convictions. In a much greater measure the same is true of the masses.

At this point you may have already realized that a thorough-going study of authority is indispensable for the understanding of society. Humanity is no longer at the state of direct coercion; but neither has humanity reached the state of a universal reasonableness which would extend to every phase of human life. Men accomplish their subordination to existing conditions mainly by letting these conditions become part of their will and then act accordingly. Neither coercion nor reason are exclusively responsible for the form of present-day societal life. It is rather the faculty of man to act in harmony with authority, which has determined the profile of history. If this faculty had been lacking in the make-up of human beings, it would have been absolutely impossible to give cohesion to society. Consequently, the study of how this faculty has been developed, how it has been modified in the course of time, together with the prediction of the future form of authority, constitutes an important chapter of sociology.

Having laid down the first conceptual differentiations, I shall proceed to my next task. I must outline to you those aspects of authority which are peculiar to authority of modern times compared with other historical epochs. This is a very difficult task, and I shall perhaps have to oversimplify the subject in order to be understood clearly.

In our days the concept of authority has a characteristic which it shares with all fundamental concepts. Authority does not appear as what it is, and we need therefore well-disciplined thinking to discover it among all other manifestations of everyday life. I shall make myself a little clearer yet. When I say that the individual has acted in accordance with authority not only after the 15th and 16th centuries, but even after the abolition of serfdom, a sociologist may reply: “Why, of course, this is quite obvious! We follow not only parents and teachers, but we conform ourselves to state and ecclesiastical authorities, just as we leave it to the architect to build our homes, and to the art expert to guide our aesthetic taste. We have experts in every phase of human activity, on whom we rely for the direction of affairs.” As this could be interpreted as “Sach-Autorität,” let me point to advertising: Our purchases depend on the ability of a skillful advertiser to impress us with a certain name or brand. When we buy something in a store, our selection may moreover be influenced by the clerk, and, even more easily, by a pretty sales girl. Not only in buying and selling, but also in higher cultural and social matters we are constantly under the influence of other persons and powers. Our views about the world situation as well as national affairs are to a great extent prejudged by newspapers. Whether we want it or not, we see events through the spectacles of the reporter. The radio and the movies also influence our taste and our judgments. It is unnecessary to continue this enumeration. We know that our will and our thoughts, and consequently our actions, are influenced by a great many external factors. Special branches of science, such as the psychologies of buying and selling, advertising, journalism, etc., deal with these types of influences. Now, if the subject is so well covered, what is the good of a special study of authority? Why these general discussions, since the subject before us is so clear?

Well, we think that as philosophers and sociologists, we cannot be satisfied with such easily gained clarity. A superficial study might lead us past the core of the problem and we would then fail to understand our times. We are of the opinion that we can reach an understanding of the dependence of modern man upon authorities, advertising, newspapers, political and religious prophets of all sorts, and so forth, only if we are able to demonstrate the extent of the far-reaching and specific dependence on authority of modern man, which inevitably makes him susceptible to such influences. Our present era has its particular forms of authority, just as the Middle Ages and antiquity had theirs. It would be a great error to assume that we submit to authority only when we wish to do so with our full will and knowledge, or when we invite another will to guide us.

In order to understand the problem we must inquire into what happened in society after the medieval conception of authority had given way. As you are trained in sociology, I shall not have to waste much time in explaining it. The peasant bound to the soil had to relinquish to his lord a certain portion of the product of his labor and could use for himself only the remainder. The relationship characteristic of feudalism was that of master and servant, and not of free men. In the cities, too, the relationship between craftsmen and consumers was strictly regulated. Although this latter relationship, even before the Middle Ages came to a close, had developed into one of free burghers among themselves, business life took place within relatively narrow limits, and thus the life of the individual, from the very start, was determined by very definite rules. Very little room was left to the expression of his own will. When the son of a burgher was apprenticed, he was unconditionally delivered into the hands of a harsh master and of still more brutal journeymen.

The historical process of the emancipation from feudalism, which continued through many centuries, ended in the abolition of serfdom and of the right of manorial lords to exact unpaid labor from their peasants. Concurrently with this development was the agglomeration of people in the cities, whom neither a master nor a guild could tell how to live. The old authorities of social and religious life began to crumble. But were these people actually free? Theoretically at least, they did not have to obey any person because of his inherited rights. They could do as they pleased. According to our sociologist interlocutor of a while ago, who is such an authority on authority, the roaming bands of peasants in England during the 16th and 17th centuries, and the masses of the Italian cities and in the French provinces, would have been much more independent, more “autonomous,” than modern man, for they had no newspapers, no radios, no movies, and no advertising, none of the specific instruments of authority, to influence and govern them. True enough, there were laws, but we have them today, too. Were these people after the overthrow of the feudal order, e.g., after the French Revolution, more independent than we? Or, if not, did at least no new authorities other than those which, as fundamental human phenomena had existed also during the Middle Ages, enter their lives? Did humanity from then on really organize life according to reason, or did a new authority replace the old relationship between master and servant as the foundation of social life?