[Excerpt from Horkheimer’s Letter to Adorno, 9/11/1938]1

Today, on your birthday, my thoughts are with you more than ever. Your words, “If we don't make this happen…” now sound like a program to me; whether blindly or with all due caution, it must be pursued. We must struggle harder than ever for the joys of our work, for external circumstances are gloomier than ever. (...)2 You will need all your wit and energy, and should have your—truly—well-deserved rest. I cannot tell you how comforting the thought of us is for me in these often exciting days. Although I am warier than ever, my thoughts are still circling around our ‘Dialectic’. “For the sake of our morals,” as we are wont to say, I would like to make at least one comment.

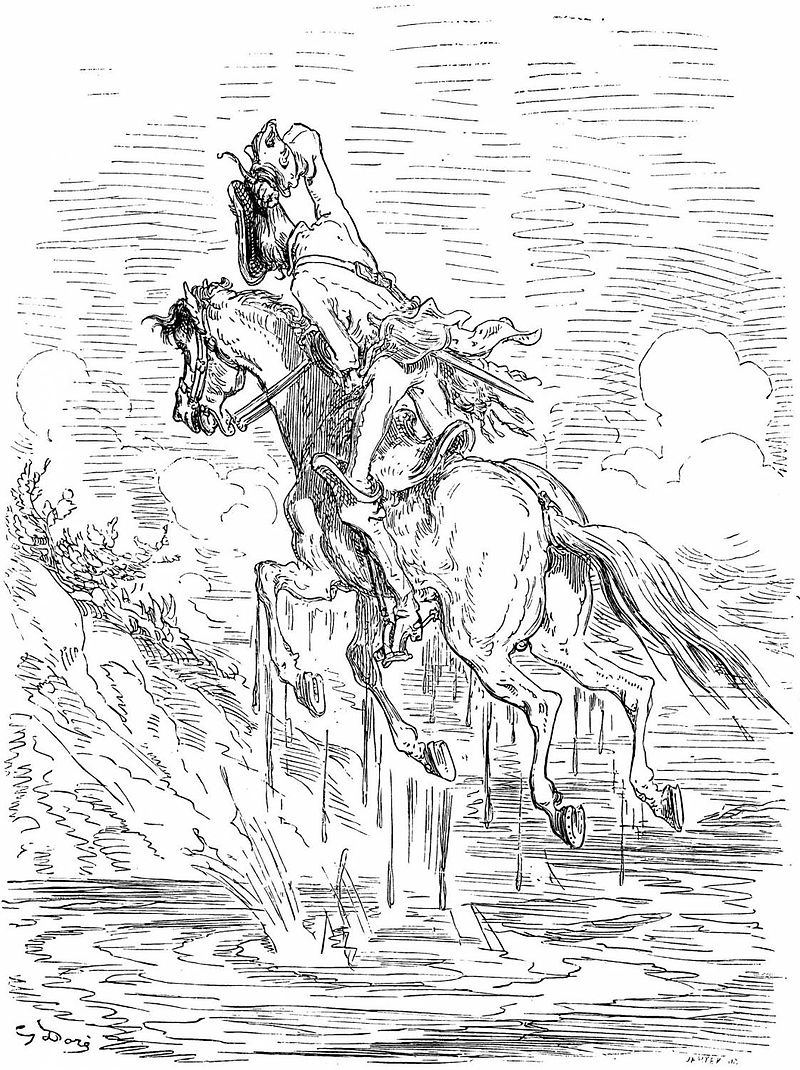

The dialectical method seems to me to have a basis in the fact that philosophizing takes place within the division of labor, and is, in essence, a product of the division of labor. However, the tendency of thought to reach beyond itself and towards the better is universal, and the possibility of reflecting on this tendency is at least as universal. Both are expressed in actions and gestures, in everything spiritual. Words and propositions are an abstract moment of this expression, albeit an exceptionally significant one. In “philosophy,” words and propositions are immediately identified with the above-mentioned tendency of thought coming into its own; and every philosophy—if it is not mystical—contains this idealism. Thus, these abstract features of language acquire bombastic function, wholly disproportionate to their actual capacity. The attempt made by language to pull itself out of the water by its own pigtails, as you would say, consists in the effort of reversing the process of abstraction by reconstruction of its individual stages.

This is the meaning of the introduction of dialogue as a philosophical method, which, at least in its origins, is characterized by demonstration of the untruth of the first assertion—namely that which arose from mere, monological thinking. The earliest philosophical texts are always and only reports of such dialogue. The character of the ‘report’ [Bericht] was soon stripped from them; philosophizing became a profession, and the author as author made himself out to be the subject of truth. When Fichte and Hegel took up dialectics again, they necessarily considered their writings processions through the absolute, though an element of the report seems to have been preserved in them too: reports of positing [Setzung], identification or equation [Gleichsetzung], non-positing [nicht Setzung], and counter-positing [Gegensetzung]. Recent philosophy has abandoned this completely. It reconstructs the process of abstraction solely in what are, so to speak, autonomous, self-sufficient words, and tries to generate concretion entirely within a sphere of its own. Whether philosophers use the concept of real history, as does historicism, or the congealing of the life-process, as does Bergson, or the transcendental reduction, as does Husserl, is of no importance. In each case, the untruth of conceptual thinking is to be overcome by indicating its derivation from actuality.

It is precisely by virtue of this activity, which remains within the framework of philosophical specialization, that philosophers are now in the awkward and ridiculous situation of having to behave towards actuality as a whole, the unconditional, the truth proper, as chemists do towards acetic acid—namely, as if it were a matter of finding the right formula. They are Einstein's quackier competitors, with a little more or a little less culture. My father's remark after visiting Husserl: “What can he say, he’s just a philosopher…”—really means: it is precisely in relation to humanity, to that tendency of thought towards the better and its reflection, that the philosopher proves to be corrupted. The philosopher has made humanity the object of his profession, and so must incessantly speak and write about it—as if speaking and writing had not long ago acquired a much narrower significance. This is why the philosopher is so impoverished—his interests, his pride, his happiness assume a false direction. Dialectics is the desperate attempt to escape the danger of stupidity which is inherent to philosophizing and contained in its reduction to words. Whether dialectics does not, by necessity, lead only to the discovery of one’s own inadequacy, as it happened to for the Hegelian school, I do not know. This we must experience through and with each other. —

Horkheimer to Adorno, 9/11/1938. In: Max Horkheimer, Gesammelte Schriften. Band 16 (Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, 1995), 478-480. Original translation.

Re: those ‘external circumstances’: “When I set out on this vacation trip, I believed that at least our financial situation was reassuring, given the circumstances. When the catastrophic news arrived from the stock market, I learned that my ideas about the extent and solidity of our investments were highly inaccurate. I had lulled myself into a false sense of security; we lost part of our assets, the amount of which I am afraid to even give you an estimate of. My first impulse was to return immediately, not so much because I could have done something so quickly, but because relaxation was now hardly an option. Then, however, I decided not to give up these long-awaited weeks with Maidon quite so quickly. We will try to complete the trip as planned and to gain as much strength as we can. And then the Pachyderms will sit together and discuss what should happen.” In: Ibid.