The Collapse of Germany Democracy and the Rise of National Socialism (9/15/1940).

The first comprehensive draft of the ISR's Germany-project.

We intend to use the Weimar Republic like a corpse, dissecting it in the hope to find an answer to the question: why did it happen?

Editor’s Remarks: Reconstructing “Collapse.”

The document below is a partial transcription of “The Collapse of Germany Democracy and the Rise of National Socialism” (9/15/1940), sourced from the Max-Horkheimer-Archiv [MHA].1

Context: “Collapse” in the Decline.

“Collapse” is the most substantial of the numerous early drafts the Institute for Social Research (ISR) produced for its amorphous “Germany-project,” which originated in mid-1939 and was drafted in parallel to the earliest proposals for the anti-Semitism studies.2 Though “Collapse” was more polished than its immediate predecessor, “German Economy, Politics, and Culture, 1900-1933,”3 the authors include a disclaimer on the table of contents that the “Collapse” proposal was merely meant to delimit a series of problem-areas in German culture, and its social bases, to “be dealt with in the project” itself but that were not, therefore, necessarily “already discussed in the outline.”4 Much as “Collapse” would be a repurposing of its predecessor, “Collapse” itself was cannibalized for another iteration of the Germany-project, “Cultural Aspects of National Socialism” (CANS), which was itself subject to intensive (and theoretically compromising) revisions in consultation with American scholars. CANS was submitted for review by the Rockefeller foundation in early March, 1941. Horkheimer writes in a letter to William and Charlotte Dieterle:

These lines are just to express our thanks for the letter and the attached [script] on February 18th. In the last two weeks the Institute has worked literally day and night on the final draft of the big project [ed.: CANS]. A small miracle has happened. A young American professor ([Eugene] Anderson from the American University in Washington) has turned up who has followed our work for many years with the warmest sympathy, even with enthusiasm, without us ever having met in person. But now his path has led him to New York and we have decided that he should lead the great work together with me if it comes to fruition. First of all, we, the whole group with Anderson, completely reformulated the project and I can say that this strenuous time was extremely fruitful for both parties. Here there was a working community between American and European traditions as intensive as has probably never existed before in the Geisteswissenschaften. The whole [affair] seemed to us a kind of model: this is how things should proceed in such areas from now on. Yesterday we both handed the project over to Rockefeller. If it is accepted, perhaps some dreams will be realized. If it is rejected, which I think is likely given our manner and method of thinking, the struggle will continue.5

The struggle would indeed continue. For a period of nearly five years—beginning with Institute-in-exile’s first truly fatal financial crisis in fall 1938,6 ending when the severely reduced ISR managed to secure external funding from the American Jewish Committee (AJC) for the “Studies in Anti-Semitism” project in early 19437—the ISR underwent an almost total restructuring. In the mid-1930s, the focus of the ISR was primarily the publication of the Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung (ZfS) (1932-1939) and finishing the synthetic multidisciplinary research projects initiated prior to exile, particularly the Studien über Autorität und Familie (1936). Through the multilingual ZfS, the ISR presented itself as a defiantly independent organ for free thinking in the tradition of the internationally-oriented German Geisteswissenschaften that had since become impossible in Germany under Nazi rule. When World War II broke out in fall 1939, the ISR’s Parisian publisher could no longer print the ZfS. It was succeeded by the short-lived, English-language Studies in Philosophy and Social Science (SPSS) (1940-1942).8 In the 1940s, the ISR would become a different creature entirely. Contrary to interpretive convention, the ISR’s primary focus from 1940 through 1948 would be empirical social research.9 “Collapse” is a unique transitional document produced in the midst of the de- and re-composition of the ISR between 1938 and 1943: it is the ISR’s attempt to reconstitute itself mid-disintegration as the preeminent scientific organ for integrated research into the decline of liberal democracies into fascism.

Method of Presentation: Spiral of Spirals.

Regarding the methodological approach of the proposal, the hybrid structure of “Collapse” makes it unique, as the project is divided into a first section for “Synthesis” and a second for “Single Studies and Documentation.” The short ‘Preface’ on method at the beginning of “Collapse” was meant to answer the kinds of questions Horkheimer received when the ISR sent out a copy of the earlier shape of the Germany-project, “German Economy, Politics, and Culture, 1900-1933,” in the summer of 1940 to prospective advisers in American universities. In a pair of letters written in English and dated 7/30/1940 (included in full in the Appendix below), Adorno attempted to reassure two respondents of the project’s viability on Horkheimer’s behalf—James T. Shotwell and Charles E. Merriam. Both had been asked to serve as advisors for the project and both expressed serious reservations: aside from their confusion about what, precisely, they were expected to contribute, both were particularly concerned about the seemingly “encyclopaedic” ambitions of the project. Adorno’s defense of the project can be broken down into three methodological formulations. The first two have a general pattern of inquiry I would call (after Hegel’s “circle of circles”) a “spiral of spirals”: on the basis of a presumptive, underlying unity of investigations across various branches of social-scientific inquiry as well as their object of research, society itself, undertaking specialist studies as a collective with the aim of discovering what that presumed unity might consist in. Both the vagueness of the presumptive unity and the element of discovery in its articulation distinguish the approach from the practice of science a priori. This is the approach, as Horkheimer and Adorno write in their contemporaneous methodological text “Notes on Institute Activities” (1941), that is supposed to enable the social theorists to avoid both the unjustifiable hubris of dogmatic-metaphysical monism and the false humility of relativistic-epistemological pluralism. The three methodological formulations from Adorno’s letters to Shotwell and Merriam are:

Conducting divergent specialist studies in multidisciplinary coordination from an integrated and integrative social-theoretical perspective. Immediately after his assurances to Shotwell that the project does not aim to be “an encyclopaedic survey of German history from 1900 to 1933,” Adorno claims that, notwithstanding the limits placed on the project by available materials and the specializations or interests of participants, the outline “has been so drawn up as to allow an enlargement of the scope of the plan while the work is actually being undertaken” and “[t]he end result might, therefore, be much more comprehensive than the project suggests.” According to Adorno, a particular advantage of the project is the ISR’s practice of dividing scientific labor on a certain collective presumption of the underlying unity of their divergent investigations in a social-theoretical perspective. The investigations, Adorno continues, are both to be on the basis of this presumptive unity and to “elucidate” what exactly this unity might consist in. Two forms of ‘elucidation’ are provided. The first is more direct: connections between independent investigations may be expressly included within the investigations themselves. (The authors of “Collapse” tend to designate these connections with the term “cross section.”) The second is more indirect: a synthesis of the independent investigations is to be presented in an introduction written for the collection as a whole.

Double-contextualization of particular cultural tendencies (a) by respective counter-tendencies and (b) general social bases. Likewise with Merriam, Adorno insists that “[t]he project is not intended to result in an encyclopaedia,” but “has much more the object of throwing light on the tendencies in the specific sections of German culture.” Where in the letter to Shotwell, Adorno focused on the manner in which the division of scientific labor would be aimed at articulating a presumed unity of social-theoretical perspective, in the letter to Merriam Adorno focuses on the unity that is both presumed from the beginning and articulated as a result between the various spheres of German social life. The “tendencies” at which the project aims to cast light are not just any tendencies but “the most essential progressive tendencies of German culture since 1900.” These progressive cultural tendencies in German culture (A: philosophy, literature, music) “suppressed by National Socialism” are to be “saved” through a combination of empirical documentation and theoretical interpretation. The uniqueness of the ISR’s programmatic approach to ‘rescue’ particular cultural tendencies, however, is that this operation only be successful if these tendencies are comprehended in their total social context: (a) in their conflict with particular counter-tendencies, with which they are co-constitutive; (b) in being traced back to the roots they share with their respective counter-tendencies in general social bases (A: economy, political history, the labor movement).

The reciprocal correction of theory and research; the rejection of abstract theory and isolated fact. In a recapitulation of Horkheimer’s inaugural address to the ISR, “The Present Situation of Social Philosophy and the Task of an Institute for Social Research” (1931), and methodological foreword on the concept of social research to the first issue of the ZfS, Adorno opens his letter to Merriam with “a few words about our program”: the “continuous interplay between theoretical and empirical work” in which “problems and hypotheses are derived from our theoretical consideration” while “the empirical results of our research lead to substantial modifications of our theoretical formulations.” Adorno explains that this results in a double-edged critical procedure: measuring the “the ideological, speculative character of the German socio-philosophical tradition [against] concrete social reality” and criticizing “mere fact collecting” from the perspective of a social theory that is both the assumption and result of their social-scientific specialist studies.

Particularly in this last point, it becomes clear that the goal of the ISR’s multidisciplinary projects like “Collapse” is to develop a second-order theoretical perspective of the relationship between given social theory (or theories) and empirical social research, or to present an “integrated picture” of modern society through “a more comprehensive undertaking,” as we read in the ‘Preface’ to “Collapse,” that includes both theoretical and empirical moments. In “Collapse,” as in all of the ISR’s most ambitious research projects, the development of a critical theory of society is too big a task for any single researcher to take on alone.10

Problem: The Concept of Democracy.

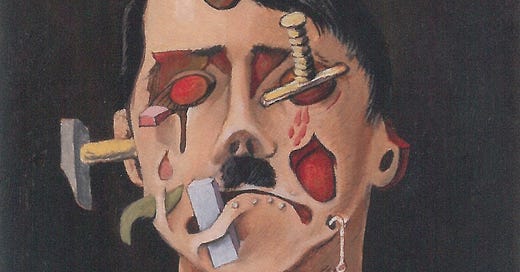

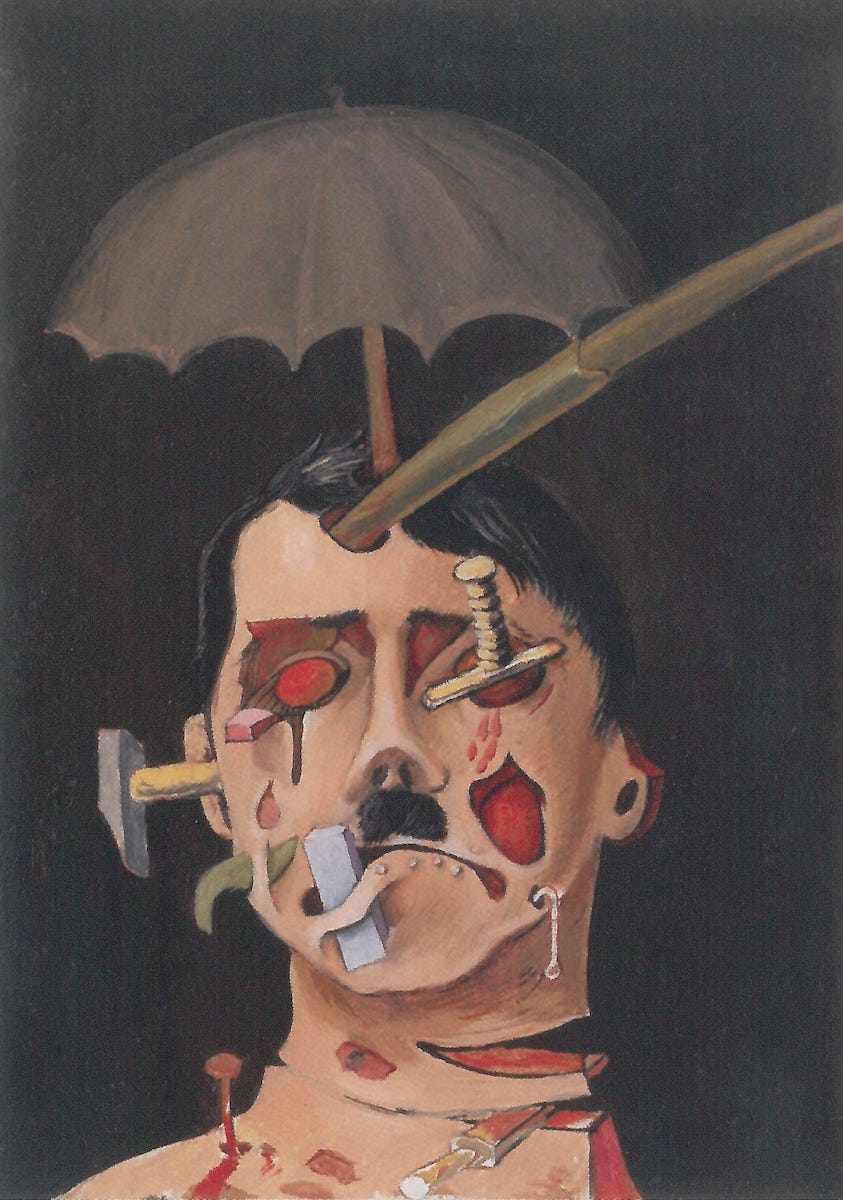

The ‘Preface’ to “Collapse” opens with the question of the reversal of German liberal (and social) democracy into National Socialism: What made it possible for Germany, a model of cultural and social progress, to be transformed into a ruthless and brutal dictatorship? The project is conceived as a kind of comparative cultural anatomy of “democratic societies”: we shall treat the Weimar Republic as an anatomical specimen to be dissected in search of an answer to the question: Why did it happen?

The point of departure for the project is a thoroughly ambivalent concept of democracy. According to the authors, it is not enough—or true—to say that Germany was simply never really democratic, or that Germany simply lacked the required number of democratic citizens, or that German democrats simply lacked the requisite will to fight for it. Any definition of democracy in the abstract that fails to account for the reversal of actual democracy into its opposite—whether it’s called totalitarianism, authoritarianism, or, in this case, fascism—is an utterly inadequate concept for any self-professed partisan of democracy, for “[d]emocracy will not live unless the people are willing to fight for it” but what the case study of Weimar Germany proves is sheer will is not enough: “It is not true that German democracy failed because there were no German democrats. For long periods, millions of Germans were willing to fight for democracy but their spirit was finally broken.” It is not enough to “know” (and teach) “the values of our democratic culture,” or even “the methods for retaining them,” but methods for fighting “the dangers [by] which [these values] are threatened.” The implication is that American democrats are as in much need of these methods in 1940 as the German democrats were in the events leading up to 1933.

The the central insight that unified each of the successive drafts of the Germany-project through the final version of CANS submitted to the Rockefeller Foundation in the Spring of 1941 was the internal connection between liberal-democratic capitalist societies and fascism. This did not go unnoticed. The American historian Eugene Anderson, the ISR’s chief consultant during the intensive revisions to CANS, was concerned that the ISR was presenting the outgrowth of National Socialism from the culture of the Weimar Republic as a necessary, even inevitable process, and encouraged them to both avoid explicit or implicit claims that the problem was “constitutional” and instead consider “alternatives which could have happened.”11 Despite the substantial revisions under Anderson’s guidance, CANS would be rejected by the Rockefeller Foundation so decisively that the ISR would abandon it and instead seek patrons for their anti-Semitism project more aggressively. John D. Rockefeller Jr. himself found the conclusion of the project “that the cultural trends leading to fascism in Weimar Germany were also present in America” so objectionable that an associate of the ISR described his reaction as so “absolutely hostile to [the] research project” that he was “not willing to finance it even if the Library of Congress should request it.”12 Even prospective sponsors who did not notice the radical implications of the project were suspicious of the ISR’s capacity to undertake such a study because of their reputation. In August 1941, Neumann writes to Horkheimer about his most recent failed effort to secure a new source of funding for CANS:

So yesterday I had the discussion with Carl Friedrich13—or rather the first part of it. I asked Friedrich for his opinion on our project “Cultural Aspects of National Socialism.” He replied that the project was excellent, provided that it was carried out by competent, unbiased and undogmatic scholars. After this explanation it was immediately clear to me that Friedrich considered the institute to be a purely Marxist affair and therefore did not trust us to be able to carry out such a project impartially. The only question was how I had to decide at that moment which tactic to adopt. I could have reacted indignantly to the veiled accusation, or I could have at least played with half of my cards on the table. I decided to go for the latter. So I asked him quite openly whether he meant that the institute was purely Marxist and, because of its dogmatic commitment, could not guarantee that it would carry out the project objectively. His answer was: yes. I then explained to him that, first of all, there is a distinction between Marxists and Marxists and, further, that it is incorrect to say that the Institute is made up of Marxists. Some are Marxists, others are not. In any case, none are directly or indirectly affiliated with the Communist Party. A conversation lasting nearly half an hour ensued in which I explained to him the theoretical foundations of the Institute and the tasks that we believe it is our obligation to fulfill. After this conversation, I asked him again whether he still maintained his original assumption. His answer was: no.14

Whenever one representative of the ISR managed to successfully convince a peer they were not too Marxist to be rigorously social-scientific in their approach, it was not uncommon for the interlocutor to respond with confused irritation: If you’re not Marxist, then what exactly are you? And if you are, then why be so confoundingly indirect?15

In at least one respect, however, “Collapse” went further than CANS. What is unique to it is the repeated appeal to a positive moment in the ambivalence that characterizes the ISR’s concept of democracy. It was almost certainly not the kind of hypothetical “alternative” of something that could have happened that Anderson had in mind. Instead, the ISR invoke a determinate kind of democracy that any self-professed partisan of democracy, whether German or American, must, on pain of destroying democracy itself, realize they are fighting for in the struggle against fascism: “a socialist order.” This is the democracy that would have demanded such “extraordinary concessions to the underprivileged,” the social-democratic government of the Weimar Republic could not stomach it. Appeal to this socialist social political order is made again and again: we are told that by the time “transformation into a socialist state… had become completely utopian in 1932,” there were no forces left to prevent the ascendancy of the National Socialists; that the identification of social democratic rule with the triumph of socialism and the suppression of revolutionary socialists by progressive social-democratic reformers was crucial for fostering proto-fascist forces of reaction and facilitating the ascent of National Socialism;16 that as soon as the social democrats ceased to consider, as the revolutionary socialists still did, the Republic a “temporary resting place and not their home,”17 was a compromise with the enemies of the radical edge of the labor movement, the only factor capable of introducing “democratic and socialist forces” into German culture,18 and initiated the process by which “[t]he socialist idea, the quasi-religious devotion, and the active solidarity were replaced by specific devices for mass domination, petty considerations[,] and passive discipline.”19 In “Collapse,” the closure of the revolutionary socialist horizon—”the impetus of the movement was no longer directed against these relations but against certain groups and conditions which most obviously hinder the functioning of the apparatus”—coincides with the emergence of a new ‘democratic’ machinery of social domination, Massenkultur and the disciplining of labor, that would train the masses for fascism.

The socialist aspect of the concept of democracy become adequate to itself in “Collapse” provides us with a key to the implied connection between the critical theorists’ continued reliance on the critical criterion of classless society and “the true idea of democracy—which even now leads a repressed, subterranean existence among the masses” in their fragmentary writings on the theory and sociology of the racket.20 To paraphrase a letter Adorno writes to his parents in 1943, throughout the ISR’s wartime research projects, all of their efforts to present themselves as social scientists investigating methods for the defense of democracy from fascist forces, they maintain a single assumption: that there is about as much similarity between the activities of the ‘National Socialist’ oppressors and socialism as there is between heaven and hell.21 The critical theorists argue that liberal-democratic capitalist societies have reached a crisis-point in which their democratic defenders are forced to decide between fighting for true democracy or endlessly engendering its opposite: socialism or barbarism.

“The spoils which fall to the fascist belong to him by right: he is the legitimate son and heir of liberalism. The wealthiest estates have nothing to reproach him with. Even the most extreme horrors of today have their origins not in 1933, but in 1919, in the shooting of workers and intellectuals by the feudal accomplices of the first republic. The socialist governments were essentially powerless; instead of advancing down to the very basis of these events, they preferred to remain on the loose topsoil of the facts. In secret, they held the theory to be a quirk. The government made freedom a matter of political philosophy instead of political practice. Even those who may privately have every reason to do so should not wish humanity to repeat this. It would run the very same course as the original.”

—Horkheimer, ”The Philosophy of Absolute Concentration” (1938).

On Reconstructing “Collapse” from the Archive.

The transcription below includes the “Preface” and “Introductory Survey”—with two significantly distinct variants (“1a)” and “1b)”) of the latter—and the six-part “Section One: Synthesis”: I. The Heritage of the Past; II. Friends and Enemies of the Republic; III. The Cultural Crisis; IV. The New Ideology; V. New Methods of Mass Domination; VI. The New Imperialism. Neither V. nor VI. are included in the polished copy of the final draft of the proposal—“1a)”—which is available in the archive. Both are, however, still listed on its table of contents (admittedly, with the proviso that just because something is listed in the ToC, “[t]hat does not necessarily mean that they are already discussed in the outline…”). Because I have been unable to locate the final drafts for V. and VI., I have transcribed their English abstracts from draft “1b).” The rest of subsections V. and VI. were drafted for “1b)” in German, and I have not yet had the opportunity to translate them.

Similarly for the contents of “Section Two: Single Studies and Documentation”: A. Economic Structure 1910-1939; B. Social Structure; C. Political and Legal Structure; D. Culture I: Philosophy, Literature, Music; E. Culture II: Education, etc. None of these special studies are included in the final revision of the project, “1a),” and the two sections on “Culture” (D. and E.) seem to have survived only as German drafts (by Adorno) with a number of handwritten corrections. Because A. and B. had already been typed out in full in English for “1b),” I have included my transcriptions for those below as well. In draft “1b),” there is no distinct sub-section C., so I was unable to supplement this gap in typescript “1a).” (Though I assume C., D., and E. were originally included in the “1a)” typescript as finalized English drafts, I haven’t been able to confirm this.)

While authorship of individual parts of “Section Two: Single Studies and Documentation” is relatively easy to determine—Friedrich Pollock was most likely the author of “A. Economic Structure 1910-1939” and “B. Social Structure,” whereas part “D. Culture I: Philosophy, Literature, Music” is explicitly attributed to Adorno in a handwritten comment on the typescript—it has been much more difficult to determine authorship of the whole. Though both Adorno and Horkheimer devoted more “libido,” to use a phrase of the latter’s, to the project on anti-Semisim, it is evident that they spent a significant amount of time and energy on the Germany project as well as it was revised again and again between Summer 1940 through Spring 1941. Aside from Leo Löwenthal, who likely performed his typical role as ISR’s in-house editor-in-chief for the duration, the bulk of the text for “Section One: Synthesis” transcribed below was most likely a result of the combined efforts of Franz Neumann and Pollock. (Neumann’s thematic area from CANS, “The Ideological Permeation of Labor and the New Middle Classes,” is effectively a condensation of the “Introductory Survey” below and the better part of the material from sub-sections I-VI.)

Future translation projects for “Collapse”:

Translation of the surviving German drafts for sub-sections “V. New Methods of Mass Domination” and “VI. The New Imperialism” from draft “1b)” of “Section One: Synthesis.”

Translation of Adorno’s German draft of parts “D. Culture I: Philosophy, Literature, Music” and the German draft of part “E. Culture II: Education, etc.,” both of which are also from draft “1b)” of “Section Two: Single Studies and Documentation.”

Contents.

Horkheimer—Letter: “… A kind of message in a bottle.”

The Collapse of Germany Democracy and the Rise of National Socialism (9/15/1940).

Preface.

Introductory Survey.

1a) variant of ‘Crucial Events’:

1b) Variant of ‘Crucial Events’:

Section One: Synthesis.

I. The Heritage of the Past.

II. Friends and Enemies of the Republic.

III. Cultural Crisis.

IV. The New Ideology.

V. New Methods of Mass Domination.

VI. The New Imperialism.

Section Two: Single Studies and Documentation.

A. Economic Structure 1910-1939.

B. Social Structure.

Appendix: Letters on the concept of the Germany-project (1940).

Adorno—Letter to Shotwell: Remembering what Germany Forgot.

Adorno—Letter to Merriam: From the studies on State Capitalism to the Germany-project and research on anti-Semitism.

Horkheimer—Letter: “… A kind of message in a bottle.” (1940)

[Excerpt from: Max Horkheimer to Salka Viertel, 6/29/1940.]22

The Institute is planning a major study of the history of Germany from 1900 to 1933, particularly of the cultural movements involving art, literature, film, etc. The material on this history will be lost if it is not evaluated now; the people themselves will be scattered and die off. The only country where such a study can be carried out is the United States, and one of the few places [here] where the people and the documents can be found together is our Institute. Our collection of material is probably one of the most complete, and we know where to get what’s missing. A significant portion of our members themselves participated in the movements in question; many other friends of the Institute, who might be open to interview, are in this country. It is impossible for us to finance the investigation entirely from our own resources. As with other projects of ours, we need funds “from outside.” We had the notion that some of the leading figures in Hollywood, whose history is inextricably linked to the period in question, might be interested in preserving this [historical period] from oblivion through scientific presentation. In any case, given what is now breaking out in Europe and perhaps the whole world, our work at present is essentially fated to be passed down through the night which has come upon us: a kind of message in a bottle. Is there anyone in Hollywood who I could persuade to support our project financially?

The reasons that, apart from those mentioned, could also animate this at the present time include the following: The Institute has been working for six years within the framework of Columbia University. Its Advisory Committee includes many of America's most distinguished scholars. The foreword to the draft of the project was written by a friend of the Institute’s, Charles Beard. Since an understanding of recent German history is imperative for the fight against National Socialism, both internally and externally, such work is in the interest of American democracy, and our group has been assured by many outstanding experts that the Institute is the right place to carry out the plan. The help we receive for our work from private sources would enable us to make a contribution to American science that is more desirable today than ever before.

The Collapse of Germany Democracy and the Rise of National Socialism (9/15/1940).

Preface.

Aims. Whatever the outcome of the present war, it is vital for Americans to obtain the clearest possible picture of the conditions in which the National Socialist regime grew, of its aims and inherent tendencies. The tensions under which we live, the rapidity of world developments, and the urgency of the decisions to be reached are not conducive to the writing of a history of Germany during the last four decades. Nor would such a history satisfy the need of the intelligent layman for an answer to the burning question: What made it possible for Germany, a model of cultural and social progress, to be transformed into a ruthless and brutal dictatorship?

Democracy will not live unless the people are willing to fight for it. In order to fight efficiently we must know not merely the values of our democratic culture and the best methods of retaining them, but also the dangers with which they are threatened. It is not true that German democracy failed because there were no German democrats. For long periods, millions of Germans were willing to fight for democracy but their spirit was finally broken.23 Our project should be regarded among other things as a contribution to the much-discussed problem of how to revitalize American democracy. For that reason we shall treat the Weimar Republic as an anatomical specimen to be dissected in search of an answer to the question: Why did it happen?24

We are not concerned solely with an anatomy of the past, however. It is the present National Socialist system which constitutes the external, and to some extent even the internal, threat to the existence of American democratic government and culture. [It is through the analysis of the National Socialist regime, its ideology, its system of mass domination, its new imperialism, that methods could be developed to defend American democracy.]25

Organization of the Project. The organization of the project is indicated by the aims. No systematic comprehensiveness is planned. The results will be presented in two sections, differing in length, method, and structure.

Section One (probably a large volume) will present the synthesis. It will open with a rapid survey of German political history from 1914 to 1939, centering around those crucial events which determined the ultimate path that Germany was to take. Six subsections will be devoted to various problems of the Republic ([I.] The Heritage of the Past, [II.] Friends and Enemies of the Republic, [III.] The Cultural Crisis), and to the structure and trends of the National Socialist regime as it developed from the conditions of the preceding periods ([IV.] The New Ideology, [V.] New Methods of Mass Domination, [VI.] The New Imperialism).26

Section one, standing by itself, should enable the intelligent layman to see the causes of the downfall of German democracy and the tendencies inherent in National Socialism. Though based on extensive research, this section will not be burdened with the scientific apparatus of tables, footnotes, and lengthy discussions of detailed questions.

Section Two (probably five volumes) has quite different aims. It will present the documentation for Section one and yet transcend it. Many of the specific problems will have been discussed in the first section, others merely intimated, and still others not mentioned at all. It will be divided into five parts: [A.] Economic Structure; [B.] Social Structure; [C.] Political and Legal System; [D.] Cultural Life I (philosophy, literature, music, etc.); [E.] Cultural Life II (mass culture, education, religion, press, and propaganda).27 Each volume will open with a brief survey of the field. [The discussed material will be selected and analyzed according to its relevance for our three major problems: why did it happen, what are the trends within National Socialism, what are the lessons for the USA?]28 They will not be textbooks, nor will they seek systematic completeness.

Method. Such a project is obviously beyond the competence of any single scholar. Nor would a mere collection of experts, producing some sort of symposium, achieve the desired result.

We hope to accomplish an integrated piece of research by the fact that the members of the Institute, each an expert in a different field of social science (philosophy, history, political science, economics, sociology, social psychology) have worked together for many years, striving to break down the boundaries between the academic disciplines and to study social phenomena not merely sociologically but also philosophically and historically.29 The very fact that most of the collaborators on this project are accustomed to working together closely and for a period of many years have developed techniques of cooperative research, should assure unity and balance. The total product would be different from the mere addition of separate pieces of research undertaken by isolated individuals. The outcome would be the best possible interpretation of the German experience.

The many books that have been written on the breakdown of Weimar democracy and the rise and history of National Socialism have contributed greatly to an understanding of these problems. However, they either deal with specific elements or approach the problems from specific angles and so they cannot present an integrated picture. The time is now ripe for the more comprehensive undertaking proposed.

The outline of this project is the product of long preparation. In part it is based on studies already completed or on research now in progress. For many years the Institute has centered part of its activities around these problems. It has assembled much of the relevant material and has completed a series of specific studies: Character structure of the German worker during the last years of the Weimar Republic. Conditions of the German middle class. Dynamics of dictatorship. National Socialist propaganda. Development of the rule of law. Penal administration and penal law. Structural changes in German post-war economics. Problems of German preparedness economy. Post-war trends of philosophy, literature, music, radio, movies, education, leisure time, etc.

Introductory Survey.

The Introduction provides a short survey of German history from 1914 to 1939, from the outbreak of the first world war to that of the second. The major emphasis rests on the crucial events of that period, those which are now revealed as the milestones in the process of the destruction of democracy and the establishment of the National Socialist dictatorship. Were there possibilities of avoiding the fate of the Republic, and what prevented the leadership from making the most of these possibilities?

Every social system must satisfy the primary needs of the people somehow. The Imperial System succeeded to the extent and so long as it was able to expand. Successful wars, a successful policy of imperialist expansion, had reconciled large sections of the people to its semi-absolutistic character. In the face of the material advantages gained, the anomalous character of the political structure was not decisive. The army and bureaucracy ruled. The Divine Right theory, the official political doctrine, merely veiled their rule. It was hardly taken seriously. The Imperial rule was in fact not absolutistic, for it was bound by law, proud of its Rechtsstaat theory. The system did not break down in a revolution. It was simply beaten in an exhausting world. It lost and abdicated when its expansionist policy was blocked.

The Weimar Democracy proceeded in a different direction. It had to rebuild an impoverished and exhausted country in which class antagonisms had become polarized. It attempted to merge three elements: the heritage of the past (especially the civil service), parliamentary democracy modeled after Western European and American patterns, and a pluralistic collectivism, that is by the incorporation of the powerful social and economic organizations directly into the political system.30 The idea was that traditional civil service would retain for the Republic the stable basis of the highly efficient and well-trained public servant and thus the continuity of life would not be disturbed. Parliamentary democracy would give Germany the most liberal and the most democratic constitution yet devised. The pluralistic element was to provide a stable socio-economic basis for the system. Social antagonisms would be transformed into social collaboration. The organizations of capital and labor, of industry and agriculture, of handicraft and trade, of producers and consumers, would settle their differences with the guidance, but not interference, of the state, and would arrive at a common policy. The threatened supremacy of the bureaucracy would be prevented by transforming private organizations into administrative bodies, and through his collective organization the individual would become part and parcel of the state.

But the system produced the exact opposite: sharpened social antagonisms, breakdown of voluntary collaboration, destruction of parliamentary institutions, suspension of political liberties, the growth of a ruling bureaucracy and the renaissance of the army as a decisive political factor.

Why did it happen?

In an impoverished, yet highly industrialized country, such a system could operate only under the following different conditions. [Rebuild a working society with voluntary foreign help; extraordinary concessions to the underprivileged; a socialist order.]31 On the one hand, it could rebuild Germany with foreign assistance, expanding its markets by peaceful means to the level of its high industrial capacity. The essence of the Weimar Republic’s foreign policy tended in this direction. By joining the concert of the Western European powers the Weimar Government hoped to obtain economic concessions. The attempt failed. It was supported neither by German industry and large land owners nor by the Western powers. The year 1932 found Germany in a catastrophic political, economic and social crisis.

The system could also operate if the ruling groups made concessions voluntarily or under compulsion by the state. That would have led to a better life for the mass of the German workers and security for the middle classes at the expense of the profits and the power of big business. Germany industry was decidedly not amenable, however, and the state sided with it more and more.

The third possibility was the transformation into a socialist state, and that had become completely utopian in 1932. The crisis of 1932 demonstrated that political democracy alone without a fuller utilization of the potentialities inherent in Germany’s industrial system, that is, without the abolition of unemployment and improvement in living standards, remained a hollow shell.32

The fourth choice was the return to imperialist expansion. Imperialist ventures could not be organized within the traditional democratic form, however, for there would be too serious opposition. Nor could it take the form of restoration of the monarchy. An industrial society which has passed through a democratic phase cannot exclude the masses from consideration. Expansionism therefore took the form of National Socialism, a totalitarian dictatorship which has been able to transform its victims into supporters and to organize the entire country into an armed camp under iron discipline.

National Socialism, notwithstanding its revolutionary characteristics, did not attain power by the violent overthrow of its constitution. The National Socialist Party had worked consistently since 1923 to seize power with the help of the existing coercive machinery of the state. Without the support of the army, bureaucracy and judiciary, without the disruption of the democratic forces, National Socialism would never have come to power. It is therefore imperative to analyze all those crucial events in the history of Germany during the past 25 years in which the anti-democratic forces showed their baleful significance and the democratic forces their inability to cope with them.33

[1a) variant of ‘Crucial Events’:]

These crucial events have a common basic structure. They reveal the growing loss of faith in the ability of democracy to make life livable, the gradual disappearance of liberalism, the emasculation of the Social Democratic Party and the trade unions, the numerical and political growth of the bureaucracy, the increasingly partisan role of the judiciary, and the politicization of the army as the focus of all anti-democratic trends. Today, we can see that the Weimar democracy owed its continued existence not to the intelligence and courage of its adherents but rather to the toleration of its enemies, who experienced the weakness of the democracy during those crucial events, and perfected the techniques of their own policy until the democracy was finally destroyed.

The following events require especially careful analysis:

Revolution 1918: The breakdown of the Imperial system was not turned into a democratic revolution. The undemocratic heritage of the past was retained in large parts.

The Weimar Constitution 1919: An admirable document on paper, it failed to create a reliable coercive machinery, to complete the unification of the Reich, to democratize the schools and universities. The Republic appeared to the masses as a merely transitory structure.

Kapp Putsch 1920: Although blocked by a general strike, the Kapp Putsch strengthened all reactionary tendencies which were responsible for it.

Murder of Rathenau 1922: The popular resentment against the murder did not crystallize into action. The Law for the Protection of the Republic was turned into a weapon against the democratic forces.

Inflation and Occupation of the Ruhr 1923: The profound economic transformations ruined the middle classes. The occupation of the Ruhr brought out an increasing nationalism organized into fascist groups supported by the Reichswehr. The Republic failed to cope with them.

Reich execution against Thuringia and Saxony 1923: The Reich Cabinet deposed the legally constituted governments in Thuringia and Saxony but did not institute action against the openly anti-constitutional Bavarian Cabinet.

Hitler’s Munich Putsch 1923: Hitler’s trial turned into a farce: after a short period of repression, the National Socialist Party was allowed to reorganize.

Stabilization 1925-1930: The New Deal of the Weimar Democracy seemed fully established. It concentrated, however, chiefly on the elaboration of its social legislation and failed to deal with the decisive problems of economic and political power.

The Policy of the Lesser Evil 1930-1932: Social Democracy accepted the emasculation of parliamentary sovereignty and the suspension of many civil rights.

The Papen Coup d’Etat 1932: The Social Democrats added ridicule to their weakness by countering the deposition of the Prussian Cabinet with nothing more than a law suit. The reliance upon legal and parliamentary action proved a complete failure.

Hitler’s Access to Power, January 1933: Social Democracy, trade unions and liberals, as well as democratic Catholicism, fatalistically accepted Hitler’s appointment because in form it was done in the usual constitutional way. The election of March 5, 1933 foreshadowed the terroristic character of the new regime.

The Submission of Labor, May 1933: The trade unions attempted to make their peace with National Socialism by dropping their political affiliation with the Social Democratic Party. They failed.

The analysis of these crucial events evokes the key questions which underline our whole project. They may be divided into six groups:

I. Economy.

Was the concentration of capital and the failure of antitrust policy instrumental in the collapse of the Weimar Democracy?

Why did heavy industry, in contrast to the light industries, join forces with National Socialism just as they had done in Italy?

Did the system of state interventionism (public ownership, currency control, public control of coal, potash, and other industries) have any bearing upon the strength of the democratic forces? Was it possible to organize the control of business (even economic planning) within democratic forms?

To what extent was the inflation responsible for undermining the economic strength of the middle classes?

Were the devices introduced to protect the economic status of the middle classes in the face of growing monopolization (credit facilities, cooperatives, political organization) adequate?

Was the retention of the traditional forms of agriculture inevitably bound up with inefficient obsolete methods of agricultural production?

Would more extensive resettlement projects have helped to solve the agricultural problem under German conditions?

Was the system of public works (with or without a resettlement policy) an adequate solution of the German unemployment problem?

II. Social Structure.

To what extent did the process of bureaucratization in key social organizations like the trade unions destroy their initiative and militancy?

What were the consequences of the direct affiliation of the trade unions with political parties?

Was the social legislation (social security, compulsory arbitration, etc.) a contributory factor in weakening the resistance of the trade unions against the incorporation of labor into a totalitarian system?

Why did the so-called “old middle classes” (handicraft, retail trade, free professions) join forces with the very groups who constituted the major threat to their existence, big business and the Junkers?

How did the increasing differentiation among the workers (supervisory workers, white collar workers, skilled, semi-skilled and unskilled laborers, women) affect their resistance to National Socialism?

Did the social composition of the bureaucracy contribute materially to its essentially anti-democratic character? Were the organizational forms incompatible with democracy?

III. Political System.

Why did the suspension of civil liberties in periods of emergency, intended to facilitate the fight against anti-democratic forces, actually strengthen reaction?

Was the concentration of political power in the hands of the Reich President a method of safeguarding democracy?

What were the merits and weaknesses of the Reich Economic Council, municipal self-government, and the pluralistic system as a device to check the growing power of the bureaucracy?

Did the system of proportional representation, with its protection of small minorities (splinter parties), facilitate the growth of National Socialism?

What effects did the federated structure of the Reich have on the attainment of a democratic consciousness?

What was the role of political Catholicism in the struggle for democracy?

Why did the most powerful democratic party, the Social Democrats, fail so completely?

Why have the liberal middle classes completely disappeared as a political force?

IV. The Army.

To what extent was the fact that the army was made up of professional soldiers under an officer caste decisive for its anti-democratic policy? Would universal conscription have helped to prevent the army from becoming a state within the state?

What were the relations between the army, high bureaucracy, big business and lard land owners?

Why did parliamentary control of the army fail?

V. The Legal System.

Why did the legal weapons against anti-democratic forces become tools for undermining democracy?

Was the system of career judges preferable to one of elected judges, and to the jury system which had been abolished in 1924?

Were the modern German schools of jurisprudence (sociological jurisprudence, rationalistic school, school of free discretion) instrumental in undermining the rational legal system?

VI. Culture.

Why did the progressive criticism of 19th century culture, as offered by Nietzsche, change into a retrogressive trend?

Were the anti-rational trends in philosophy (vitalism, Existenz-philosophy) intrinsically linked with the degeneration of democracy?

To what extent did the “mass-culture” of the Weimar period contain germs of totalitarianism?

Why did the German educational system fail to train militant democrats?

What were the National Socialist propaganda techniques and why did the democratic forces fail to utilize them?

[1b) Variant of ‘Crucial Events’:]

The experience of the past few years has shed new light on political, social and economic trends which hitherto have been neglected. Certain historical factors such as the changes in the form of state and government had previously been overemphasized, while others, such as the role of the bureaucracy, the army, certain economic groups and their interconnections, are not yet adequately analyzed.

1914/18: Political Truce.

The constellation of the social-political forces during the World War becomes decisive for Weimar Democracy. The war reveals two trends, the limit of the integrating power of the Imperial system, especially of its bureaucracy and army, and the profound transformation of Social Democracy and the socialist trade unions.

The war clearly demonstrates that a semi-absolutistic state of the old Prussian type cannot, in an industrialized society, continue in its existence unless it succeeds in its expansionist policy. The war brings the scope and the efficiency of the bureaucratic and the army machines to their highest technical perfection (War Economy). Yet, it proves incapable of providing the integrating ideology for the subsequent defeat. There is a chance for the Labor Movement, which aims at the establishment of a new society, to disrupt the magic circle. But Social Democracy has entered into a truce; it will stick to it in spite of internal dissensions and the betrayal of every promise by the Hindenburg-Ludendorff dictatorship. The trade unions have become administrative agencies of the state. The marriage between the state and the social organization of labor is being consummated. Labor is unable to liberate itself from the impact of the past.

The following questions arise:

What was the impact of the War Economy on the future economic structure of Germany?

Why have the Social Democrats and the trade unions, in spite of their pre-war revolutionary ideology, opted for defense, and actively collaborated?

1918: Missing the first chance.

The breakdown of the Imperial system opened the way for a social revolution. It did not materialize. The anti-revolutionary policy of the Social Democrats expresses the sentiment of the politically untrained masses: yearning for demobilization, peace, democracy. Already the First Congress of the Worker’s and Soldier’s Councils (December 16th, 1918) decides with a huge majority for the convocation of the National Assembly. All revolutionary attempts for a radical transformation of the political system are violently suppressed. The new authorities do little or nothing to occupy the vital positions for preventing the old powers to regain what they lost.

Far from overthrowing the old bureaucratic machine, the Social Democratic leaders in fact strengthen it. Outwardly, at least, the decisive political force, they prefer to rely far more on the old bureaucracy than on the masses. They do not seize the opportunity of engendering a system of active, mass-borne democracy.

The following problems arise:

Why has, in contrast to Soviet Russia, the revolutionary movement failed?

Was the transformation of Social Democracy and the trade unions into reformist organizations inevitable?

What was the role of leading personalities?

Have foreign powers contributed towards the defeat of socialist revolution by strengthening reaction?

1919: The Constitution of Illusions.

The constitution of August 11th, 1919, as it stands on paper, is an admirable work. But its deficient social basis threatens its successful operation from the very beginning. Due to its pluralistic origin, the constitution is the result of a set of covenants between powerful social groups, mainly the following:

The agreement Ebert-Hindenburg of November 9, 1918, with the understanding to fight bolshevism and restore peace and order.

The agreement between the employers and the trade unions (the Stinnes-Legien compact) of November 15, 1918, which promises the workers equality in the shop, recognizes collective bargaining, and denies the employers’ protection to yellow labor organization.

The understanding between the government and the Social Democrats (March 22, 1919) promising the incorporation of the worker’s council system into the constitutional framework.

The agreement between the “revolutionary” governments of the Reich and the State (January 26, 1919) maintaining the federative structure and securing the indivisibility of the Prussian territory in spite of the unitarian program of the Social Democratic Party, to which most of their members belong.

Finally, the understanding between the partners of the Weimar Coalitions (Social Democrats, Democrats, and Catholic “Center”) which comprises all previous agreements and recognizes and secures in the very text of the constitution the status of the civil service and of the judiciary, while at the same time it secures the recognition of the churches and political corporations.

The constitution thus tries to mold into a whole the old Prussian tradition, the Western democratic models, and the demands of the working classes. But a pluralistic system, far more than an individualistic democracy, can only operate if the contracting social partners are willing to compromise. The constitution that embodies this system rests on the assumption that society’s basic interests are fundamentally in harmony. No attempt is made by the Republicans to give their state weapons ensuring its functioning when compromises no longer work. Then either one social group will conquer power, or the old bureaucratic and military forces will arrogate it to themselves.

The following problems appear significant:

What fundamental features of German society were neglected by the constitution makers? Could they have acted otherwise?

What is the role of political Catholicism in the Weimar Democracy?

What is the cause for the disintegration of the Democratic Party?

How did the pluralistic system operate?

1920: The democrats lack “Will to Power.”

March 1920. The reactionary Putsch led by Kapp and General Luttwitz breaks out. A general strike sweeps the Kapp government away. Wide masses of the bourgeoisie, frightened by the oncoming reaction, are willing to submit to the leadership of the Social Democrats. But the attempts to form a worker’s government to replace the Cabinet of the Weimar Coalition fail. The Reichswehr is allowed to shoot those workers who refuse to lay down the arms they have taken up for the defense of the Republic. The Republicans miss the opportunity to ensure the protection of the Republic after they have shunned the danger of the Putsch. The Social Democratic and Democratic parties are beaten in the June elections, 1920. The majority of the Independent Social Democratic Party, despairing of success by democratic means, joins the Communist Party which thus becomes a mass organization. The split among the German workers deepens. Since June 1920, a bourgeois Cabinet rules in which the German People’s Party, the representation of industry, shares power. The chance which the defeat of the Kapp Putsch offered to exterminate the counter-revolutionary forces is completely wasted. It is turned into its opposite. The reaction is strengthened.

The following problems deserve attention:

Is the Putsch an adequate means of counter-revolutionary activity in industrial society? A typology of counter-revolutionary tactics will be attempted (Junta; restoration; dictatorship; Fascism and National Socialism).

What was the impact of the general strike? Did it merely succeed because it was sponsored by the legitimate government? Is the general strike an adequate weapon to fight reaction?

What is the role of the army? Does its role depend upon whether it is built on universal conscription or whether it is composed only of professional soldiers?

1922/23: the democrats yield their power.

Under the protection of the Cabinet and the Reichswer, anti-democratic reaction becomes more daring. Secret military organizations appear. They already have a fascist character. In June 1922 the Reich Foreign Minister Walter Rathenau is murdered. Enormous popular resentment rises. A Law for the Protection of the Republic is enacted, but, in the hands of a reactionary judiciary, it soon becomes a tool for fighting left opposition while the counter-revolution remains unmolested. Another opportunity is missed.

On January 11, 1923, France occupies German territory as a pawn for reparation payments. The government of Chancellor Cuno organizes passive resistance against France with the active collaboration of the Social Democrats and the trade unions. Nationalism becomes ripe. Communists and fascists vie with each other in nationalistic demagogy. The outcome of the Rhineland occupation is a sharpening of the inflation which ruins the middle-classes and upsets the German social and economic structure. The middle of 1923 sees a genuine revolutionary situation. There are no forces to exploit it but the inflation profiteers. The Communist Party misses its opportunity and merely attempts a locally isolated Putsch which is bloodily, yet easily, repressed.

The following problems appear decisive:

The role of the judiciary in a democracy. Professional or elected judges? Is the jury system a guarantee of freedom?

Why has the Communist Party failed to utilize the revolutionary situation?

What was the economic and social impact of the inflation on the concentration of capital, on agriculture, and on the middle-classes?

1923/24: The old ruling groups back again.

The Cuno Cabinet is overthrown by a spontaneous strike wave. But the first Stresemann Cabinet in which the Social Democrats enter to end Ruhr resistance orders the Reich Execution against Saxony and Thuringia (October 29, 1923), the first Reich Execution to be enacted against any legally constituted state. The governments composed of Social Democrats and Communists are deposed. The successful democratization they had carried out within the administrative and judicial machinery is reversed. The very same Stresemann government, however, fails to enforce the fundamental tenets of the Reich policy against the reactionary Bavarian Cabinet which daily violates the constitution.

The Stresemann Cabinet ends the passive resistance and undertakes the stabilization of the Mark. But to attain economic stability, it, for the first time, fully uses the dictatorial powers contained in Article 48 of the Constitution, for purposes by far exceeding the powers granted by this article (e.g., for measures regarding currency stabilization, for the abolishment of the 8-Hour-Day, for the introduction of compulsory arbitration of labor disputes). So strong has the government become that Hitler’s Munich Putsch (November 9, 1923) is easily defeated. Having done their duty, the Social Democratic ministers are sent home. A pure bourgeois Cabinet is instituted. Neither the government nor the victims of inflation try to change the profound consequences in the distribution of economic power and wealth resulting from the expropriation of the middle class.

Problems:

Did the federative structure of the Reich play any role in the rise of German counter-revolution? Did it facilitate or hinder it?

How has the failure of the Bierkeller-Putsch influence the future policy and ideology of the National Socialist Party?

How does the impoverishment of the middle classes and the workers affect the economic structure as a whole?

1924/28: Stabilizing the new social structure.

The new cabinet, where big business finally shares the responsibility of government, appears to the Western democracies as a worthy partner. The Dawes Plan is the result. Yet, Stresemann’s policy of reparation fulfillment needs the consent of the Social Democratic opposition. It is easily attained. The Social Democracy does not prevent the enactment of the new tariff policy which will enhance the economic and political power of the big landowners. Socialism has ceased to play a decisive political role.

Loans flow into Germany. Industry is reorganized. It is standardized, mechanized, and rationalized. It attains the highest technical efficiency and the highest productive capacity of all European industrial systems while, at the same time, the process of cartelization and trustification rapidly progresses. The death of President Ebert brings Hindenburg, the nominee of the agrarians, the industrial monopolies, and the monarchist middle-class leaders, into the presidency.

Meanwhile, Germany again appears to be a normal country. Prosperity reigns. Social legislation is continually improved (establishment of Labor Law Courts, Unemployment Insurance, protection against dismissal of old employees, and so on). At the same time, the trade union machinery and the state machinery become more and more intertwined. The Social Democratic Party wins back the confidence of its adherents. The election of May 20th, 1928, brings it huge success. Again there is a chance.

1928/30: The policy of the lesser evil.

Will to power is not the result of the Social Democratic victory. A Socialist led Cabinet is formed to carry out Stresemann’s foreign policy (Locarne, League of Nations, French-German understanding), but it compromises Stresemann’s People’s Party, increasingly dominated by industrial monopoly interests.

The start of the Mueller Cabinet is ominous. While the Social Democratic Party went into the elections against the building of the battle cruiserA, one of the first deeds of the Cabinet was its decision to continue the naval building program. The socialist masses sharply resent the betrayal of the traditional anti-naval policy of pre-war Socialism.

The final blow against the Cabinet is caused by the socialist trade unions, in 1930, at the onset of the economic depression. At this stage trade unions are not willing to make concessions to the bourgeois partners of the Cabinet on the question of the unemployment insurance contributions. Mueller has to resign. Breuning is appointed. His emergency legislation, issued under Article 48, is rejected by the Social Democrats. The President dissolves the Reichstag.

New elections are held on September the 14th, 1930, and 107 National Socialist Deputies, corresponding to more than 6 million votes, are returned. The Social Democratic Party is frightened and will now yield to Beuning’s deflationist policy in order to “prevent the worst.”

Problems:

Why has the middle-way of the Social Democrats with their program of an economic democracy, in short, the New Deal, failed?

Is the politicization of the trade unions and their close interrelationship with the state a sound development?

Have state interventionism and social reform facilitated the rise of authoritarianism?

Why have the middle classes, although their existence was primarily threatened by the trustification of industry, opted for reaction and not for progress?

1930/32: End of parliamentary government.

As early as 1929, at the occasion of the fight against the Young Plan, had the agrarian-industrial reaction joined forces with the National Socialists. With the exception of parts of his own (“Center”) party and the insignificant Democratic Party, Breuning’s political strength depends entirely upon the “toleration” by the Social Democrats. Yet, neither they nor the “Center” are able to determine the policy of the Cabinet. It is the agrarian-industrial reaction and Breuning’s hope to tame the National Socialists by bringing them into his Cabinet that solely guide him. The result is a rigid deflationist policy in order to counter the ever-deepening depression and the strengthening of the presidential power through the application of Article 48. Parliamentary government has ceased to function. Breuning’s overthrow is due to the growth of the reaction whose claims are increasing every day, whereas the Social Democrats and the trade unions merely occupy defensive positions and the Communists concentrate their attacks on the “social fascism” of the Social Democrats.

Problems:

Is it compatible with the principles of a liberal democracy to suspend the fundamental liberties in order to fight against anti-democratic forces?

Is the concentration of political power in the hands of the executive and the suspension of parliamentary institutions an adequate means of fighting reaction?

Why have the democratic political parties in Germany not perceived that anti-democratic mass movement cannot be fought merely by parliamentary means?

1932: the first coup d’etat.

In logical pursuance of their toleration policy, the Social Democrats decide to vote for Hindenburg against Hitler as President of the Reich. Hindenburg is reelected primarily through the efforts of Breuning whom he soon throws out and replaces by von Papen. Papen receives the power to depose by federal action the Prussian Coalition Cabinet led by the Social Democrat Otto Braun. On June 20th, 1932, the “coup d’etat” starts. Neither the Social Democrats not the trade unions nor the Communist Party offer the slightest resistance. Without a shot, without a strike, the Social Democracy abandons its most powerful positions: the Prussian Administration. It restricts to merely parliamentary means its opposition to the Papen Cabinet. It even adds ridicule to its inability – the deposed Prussian Cabinet sues von Papen before the Reich Constitutional Court. Yet, in taming the National Socialists, neither von Papen nor his successor, General von Schleicher, will succeed. Combined intrigues of the East-Elbian agrarians and of the heavy industries (Thyssen) induce Hindenburg to appoint Hitler Chancellor, in succession of von Schleicher, on January 30, 1933. No violation of formal “legality,” awfully respected by the Republicans, occurs. Therefore, Hitler meets with no resistance at all.

Problems:

How is the legalistic fanaticism of the Social Democrats to be explained which, in contrast to the National Socialist legality, was not merely a ruse but honestly believed?

Why has the Communist Party again failed to take the initiative in the fight of the workers against the Prussian coup d’etat?

Why has heavy industry (Coal, Iron, Steel), in contrast to the light industries, actively supported the National Socialist movement in Germany, as in Italy before?

1933: the second coup d’etat.

The first month of Hitler shows a more or less normal reactionary regime, still clothed in the veil of legality. Hitler seems to have been, at last, tamed by the majority of “old guard” Nationalists in his Cabinet. But the fear that the coming Reichstag elections of March 5, 1933, might not bring the National Socialists the desired majority, and the brake which his coalition partners apply to his attempts to physically exterminate the opposition, lead the National Socialists to the famous Reichstag fire. They thus create a legal pretext to imprison all Communist leaders and prohibit the whole Communist and Social Democratic press. The elections are held but the terror reigns. That is Hitler’s coup d’etat. 51.8% of the frightened electorate approve of the new government. The coup d’etat has ensured the legal continuation of the terror regime, but has not brought about its own majority for the National Socialist Party. The Workers’ Council Elections held shortly afterwards show again that Hitler has not got the majority and, especially, that the inroads which the National Socialist movement has made into the working classes are negligible. Still no resistance arises.

[1933:] Labor’s capitulation.

Immediately after Hitler’s appointment the socialist trade unions began secret negotiations with the National Socialist organizations. They openly divorced themselves from their long association with the Social Democratic Party, they declared their political neutrality and they even acclaimed the legislative designation of May-Day as a national holiday to be the fulfillment of trade union wishes. Their negotiations were of no avail. On May 2nd, 1933, Brownshirts occupied the trade union buildings, arrested the leaders, and appointed National Socialist commissars. That period of conquest was soon followed by the complete destruction of all labor organizations and their replacement by the German Labor Front.

The Communist Party had already been banned before the elections. The Social Democratic Party was dissolved on June 22, 1933. On July 14, 1933, a statute against the formation of political parties was enacted. The familiar process of the coordination of the whole political and social life of all autonomous organizations, whatever character they may have and whatever aims they may pursue, was in full swing.

It is not necessary to trace the further development of National Socialism at this time. That will be done in the subsections dealing with Mass Domination, the New Ideology, and the New Imperialism.

Problems:

How is the futile expectation of the socialist trade unions in Germany (as previously in Italy) to be explained?

Why has German National Socialism, in contrast to Italian Fascism, completely dissolved the syndicalist structure?

That leads to the question of the sociological principles underlying the National Socialist policy of coordinating every social organization. We have to analyze the principles of atomization and differentiation.

[1934:] Democratic abdication.

After the purge of June 30, 1934, in which the last remnants of inner National-Socialist and conservative opposition were bloodily exterminated, the German people is no longer capable of influencing the direction of National Socialist policy. The regime is total. The opposition is exiled, imprisoned, terrorized, dead, or has changed camps. National Socialism can only be opposed by the surrounding world. From now on, the growth of National Socialism is primarily due to the foreign policy of the Western Democracies. No comment is needed at this time. The analysis of the foreign policy will be undertaken in conjunction with the investigation of the New Imperialism.

Section One: Synthesis.

I. The Heritage of the Past.

It is much too superficial to label the phenomena of recent German history as characteristic products of the “German national character” or of the “Germanic race.” The heritage of the past undoubtedly has a certain weight in the present. This section will isolate National Socialism’s specific German traits which are rooted in the German socio-political structure. This isolation will enable us to find out to what extent National Socialism is merely a particular German phenomenon and to what extent a more universal trend. This heritage is complex, however. Its origin in the particular characteristics of the German political system cannot be grasped unless the complex “whole” is dissected into its historic components.

The historical residues that are still effective form several strata which overlay and interpenetrate each other. In a rough system of classification, we may distinguish the heritage of feudalism, of the mercantile, cameralist Prussian military state and of the imperial epoch.

Prussian tradition stretches into the present as the dual heritage of feudalism and the cameralistic state, transformed by the specific requirements of the period of capitalist growth. The originally feudal latifundia were transformed into capitalist grain factories because of the emancipation of the peasants in the first half of the nineteenth century. The large landowners, traditionally members of the socially and politically ruling stratum, merged with big industrialists to form an economic aggregate, which will be discussed in section II. The bureaucratization of the entire social organism during the early capitalist period became one of those basic structures from the past which the Weimar Republic was not capable of changing.

The bureaucratization of society and the ruling position of the large landowners are in turn components of an historical process which transformed the heritage of the middle classes. Progressive liberalism was defeated three times in a few decades: after the wars of liberation (1812-1815), during the revolution of 1848, and during the constitutional conflict with Bismarck (1861-1865).

The complete lack of a genuine liberal tradition was one of the decisive features characterizing the frustration of the Weimar Republic. In contrast to the Western European nations, the development of the modern German state took place in an economically backward country, which, for its growth, could not depend upon its strength in international competition. The Fascist slogan of the proletarian nation has a deep-rooted historical foundation. Germany had to look for other than economic means to win a place in the world market, means which, from the standpoint of the highly organized Western European countries, appeared terrifying and destructive. Since the German Reformation time and again there has arisen the cry for a movement “from below,” the appeal to the oppressed instincts of the masses, the demand that the people itself take the rights which other nations already possess. For more than four centuries, liberation and prosperity were associated in the consciousness of the Germans with violent and destructive action, with hatred of the “foreigner,” with expansion by war. German philosophy, literature, and theology are tinged with a militant chauvinism, with the glorification of irrationalism, and of the primeval entity of the Folk and its creative power. The fate of the Weimar Republic was determined by the fact that at the opposite pole of the society, within the labor movement, a reverse tendency had taken place. It is as if the forces of “law and order,” of peaceful legal stabilization and consolidation were diverted to those social groups which seemed destined to overthrow the social system. Since the turn of the century, large strata of the working population were slowly but systematically reconciled to the existing state. The Social Democratic Party was transformed from a revolutionary into a bureaucratic organization, and its economic, legal, and political apparatus became the guarantor of the functioning of the whole.

The bureaucratization of the Social Democratic Party gave birth to tendencies which prepared the workers for the reality of National Socialism. Eduard Bernstein’s famous statement that the movement is everything, the goal nothing, did not anticipate National Socialist slogans merely by accident. The goal of the establishment of a new society was abandoned because the movement was no longer directed against the existing society. The laws of the capitalist process were regarded as inevitably promoting socialism, and every step in the development of capitalism was interpreted as a step towards its transformation. A powerful organization was built up, and it complied in toto with those mechanisms and became increasingly detached from all aims transcending the existing order. Moreover, the abolition of this order became thought of as a “catastrophe,” as something that would frustrate the aim rather than fulfill it. The bulk of the members became the obedient tool of those who led and handled the apparatus, and the latter handled it so that the members might benefit from the given system.

The development gave large groups of people the idea that the complete rule of the social democratic apparatus was identical with the triumph of socialism, and that it could be achieved without a change in the fundamental labor and property relations. Accordingly, the impetus of the movement was no longer directed against these relations but against certain groups and conditions which most obviously hinder the functioning of the apparatus. The more this apparatus was officially recognized and incorporated into the legal and political system, the more it cooperated with, and later represented, the state itself, the more the members felt themselves to be parts of a whole which must be maintained and defended. Its enemy became their enemy as in 1914. The coordinated bureaucracy was suspicious of “destructive elements”; hatred of intellectuals was widespread. The revolutionary tendencies became an opposition within the “official” labor movement and remained its foe until the ascent of National Socialism.

The Social Democratic attitude received characteristic expression in the cultural activities of the party. They destroyed the original tendencies of Marxism and completed the reconciliation of the masses. The traditional culture must be saved and taken over by the masses. This meant ridding it of all those contents which transcend their horizon and do not appeal to them. The resulting Massenkultur merely adorned the life of the masses with some leftovers from a “better world.” Cultural education became part of the process of coordination.

One of the most spectacular features of cultural coordination was the reception of Marx by large Social Democratic strata. Marx became part and parcel of that same culture which his entire work repudiated. He was heralded as a great German, as a hero of science who discovered the basic laws of the social reality as Newton did of the physical reality. The revolution was dissolved into sociology and its theoretician was admitted into the ranks of the dead classics.

The ideological structures of nearly every section of the population were influenced by the bureaucracy and the army. The attitude of the civil servant was a composite of belief in incorruptibility, authority, monarchic tradition, and his personal living conditions. He considered himself superior to “the ordinary man” and his state, with the “best administration in the world,” far superior to its subjects and to the outside world. One result was a formalized concept of legality; it was directed towards the offices, the form, and red tape. The civil servant was not only free from parliamentary and other forms of public control and criticism, he was not merely respected as the incarnation of an education which grants social status. His permanent tenure made him a veritable rocher de bronze within the social whole. All this also applies to the army officer with slight differences. For him the concept of legality was replaced by that of subordination and the attributes of education by those of the uniform.