Note: Horkheimer's "Science and Social Need" (1934)

Critical Theory in the Broken Middle. (Postscript: Texts from the '36 'Studien')

Contents.

Note: Horkheimer’s “Science and Social Need” (1934).

Postscript: Texts from the Studien (1936).

A. [Excerpts] International Institute of Social Research: A Short Description of its History and Aims (1935).

B. Foreword (1935)—Max Horkheimer.

C. Communique from an Expert (1936)—Karl Landauer.

D. Sketch of a Resumé for the Authority Volume (1937?)—Julian Gumperz.

Note: Horkheimer’s “Science and Social Need” (1934).

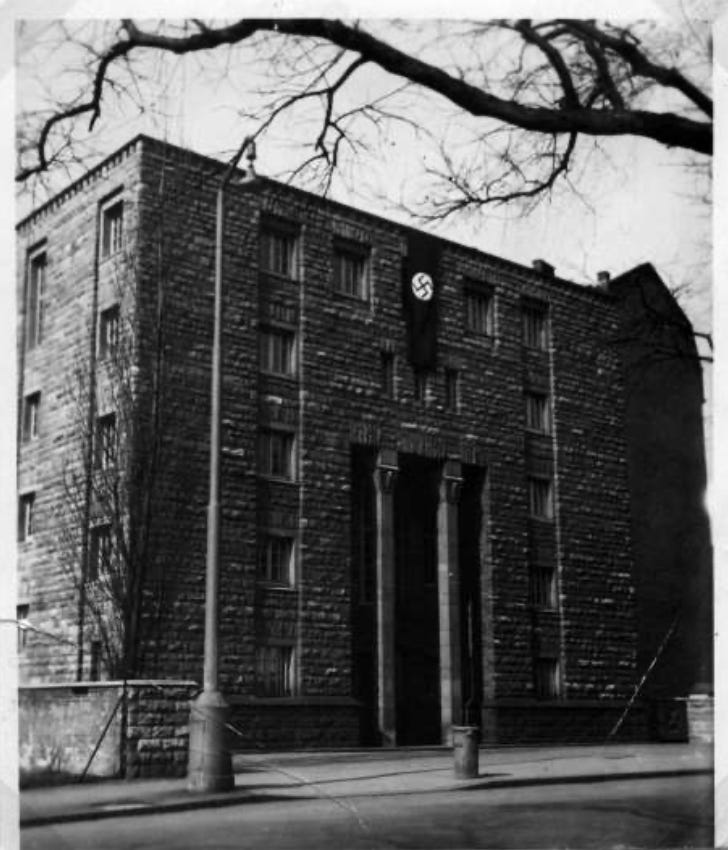

In the spring of 1933, the premises of the Institute for Social Research (ISR) at Frankfurt University, only just vacated by its fellows and staff, were raided by state police and shuttered.1 The ground floors were put at the disposal of the Nazi Student League. In short order, the ISR’s building was confiscated under new legislation for the seizure of communist assets—on the pretext of promotion of activities hostile to the Prussian state—and those members and sponsors of the ISR in the employ of Frankfurt University were officially dismissed under the act for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service, which provisioned for the mass dismissal of Jewish, communist, and social democratic civil servants in an attempt “to tackle the Jewish Question.”2 From its temporary administrative headquarters in Geneva, the ISR distributed two versions of a multilingual questionnaire to, on the one hand, a number of youth organizations with members aged 18-25, and, on the other, various experts (academics, social workers, and local authorities) in Switzerland, Austria, France, Belgium, and Holland. The questionnaires were ambitious in scope, soliciting reports on changes in authority relations within the family structure given variations in its financial support relative to differences in class position3—a continuation, under conditions of dispersal and exile, of the research project that would be published as Studien über Autorität und Familie [Studies on Authority and the Family] (1936).

One respondent in Switzerland, Reverend E. Burri, replied in the spring of 1934, initiating a brief correspondence with Horkheimer. Burri objected to the request itself: the time for collecting social-scientific research and refining the methods of social analysis had passed; it was time for action. Horkheimer answered in two letters, later published in a newspaper under the title “Science and Social Need” (1934), with commentary, by Burri.4 In this exchange, Horkheimer adopted a tactic he would describe nearly a decade later as a “hidden attack”: one which the recipient may not even feel, and which, if it does not offend them, may even please them.5 In a first letter, dated March 12th, 1934,6 Horkheimer answered:

If you will permit it, I would make my standpoint regarding your letter of March 6th known to you. I do not do so to compel you to answer for your opposition to science, which, by the way, I understand very well, but simply so as not to leave your accusations against science and its representatives unanswered. When you say scholars are not suited for promoting breakthroughs in justice and morals, I cannot but agree. But it seems to me that you draw a false conclusion from this. According to you, they should abandon their work and no longer conduct any research, no longer gather any data, and above all not write any dissertations, these having primarily provoked your disfavor. You want “action” now. It seems to me that you forget that it is precisely action not guided by reason that has led to the greatest disasters in the course of history. Aren’t the wars, the firefights breaking out within states, the economic crisis, the unemployment, and the other disastrous realities that you justifiably lament precisely the consequence of too little reflection, that is, the consequence of a will to change that is unsupported by the requisite thinking? There is certainly no lack of rationalistic and useless thinking in the science of the last decades;7 but what is needed today is good sense, an uninhibited striving for truth. If people do not use the results of scientific investigations, it is not the fault of science, as one cannot ascribe their failure to a deficiency in a machine they don’t use. The authorities who have no scruples and whom you accuse of sinning against all humanity would certainly be in agreement if people, instead of improving defective science, were to abandon all systematic reflection and spare the intellectual effort. It is not because a number of scientists have written books that they failed to fulfill their task, but because they have written bad books!8 People of goodwill like you, and those with such pointed criticism, should inspire and stimulate science rather than condemn it. Forgive me if I do not leave your opinion, to which I am thoroughly sympathetic, uncontradicted, in order to defend my profession. I am certain that you will agree with me when I remind you that common sense and the willingness to act alone are not enough to lead humanity out of the present crisis. As you try to do your best it seems to me that the task for us, other scholars, is not to neglect the work we have already begun but to continue in a spirit that tries to better adapt it to the true needs of humanity than has been the case in sociology in recent times.9

We can infer from Horkheimer’s second letter, dated March 19th, 1934,10 that Burri’s response to the first letter was, though not an apology, a significant qualification of the original charge:

My utmost thanks for your kind words. They have proven I was not wrong in the assumption that you do not condemn science in itself, but rather a science which is not conscious of its duty towards humanity. The charge you raise against the decay of science into purely descriptive work accords with my innermost conviction. I have always struggled against this superficial conception of scientific efforts, which must not be satisfied with the compilation of facts, but arrive at theories with practical implementation. As you have so aptly said, the aim of eliminating a wrong ought to guide every scientific investigation from the outset if one does not wish to add another to the list of superfluous books. Description is only a natural condition of science, but it remains without value if it does not advance to the explanation of causes.11 Perhaps we will someday have the pleasure of discussing the economic theory you mentioned in your last letter. If so, I will be able to explain in greater detail the meaning of our institute’s investigations, and you will surely see that we do not have another new dissertation as our goal.

In these open letters, Horkheimer provides a decidedly more popular reformulation of the crisis-theoretical core of early critical theory. This core was first introduced in the theses that opened the first issue of the first volume of the ISR’s Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung (ZfS), titled “Notes on Science and the Crisis” (1932), which open with the words “In the Marxist theory of society, …” and contextualizes the crisis internal to the sciences in the universal crisis of capitalist social production and reproduction;12 it was subsequently developed in a speech Horkheimer delivered at a sociological congress that had also published in the ZfS, titled “On the Problem of Prediction in the Social Sciences” (1933), which includes an explicit defense of Marx’s crisis theory in addressing the problem of the particular crisis in the social sciences.13 It would, however, be a mistake to dismiss these letters as an ‘exoteric,’ and therefore vulgarized, representation of an ‘esoteric’ doctrine of social and scientific crisis.

“Science and Social Need” is a threefold concretization of the crisis as it unfolds in “the triune relation which is our predicament”—namely, through the dynamic reconfiguration of the three moments of the dialectical concept: universality, particularity, individuality.14 In the conclusion to his contribution to the ‘theoretical’ section of the Studien (1936), Horkheimer refers to Hegel’s ‘Doctrine of the Concept’ of the Encyclopedia Logic in order to exhibit the crisis of the form of the bourgeois family within the general economic crisis of capitalist society:

The education of authoritarian characters, which it [i.e. the family of bourgeois society] is capable of due to its own authority structure, is not a temporary phenomenon, but one of relatively permanent duration. It is obvious that the more this society falls into a state of crisis by virtue of its immanent laws, the less the family is able to fulfill its task in this respect. The resultant need for the state to take care of the education for authority itself to a greater extent than before, and at the very least curtail the time allotted to family and church for this, has been indicated above. This new state of affairs, however, like the type of authoritarian state which introduces it, reckons into a deeper, and patently unstoppable, movement. It is the tendency, arising from the economy itself, to the dissolution of all cultural values and institutions which the bourgeoisie created and kept alive. The means of protecting and furthering the development of this cultural whole are increasingly coming into contradiction with this culture’s true content. Even if the form of the family itself is ultimately stabilized through new measures, it will nevertheless lose its self-activating force, which is based on the free professional labor of the man, as the significance of the entire middle class of the bourgeoisie decreases. In the end, all of this will have to be supported and held together more and more artificially. Before this will to preservation, the cultural powers themselves will ultimately appear as resisting counter-forces to be regulated. While in the period of bourgeois prosperity there was a fruitful reciprocity between family and society, whereby the authority of the father was established by his role in society and society was renewed as an authority with the help of patriarchal education, the family, though obviously indispensable, now becomes just a problem of the technology of governance. The totality of relations of the present, this universal, was strengthened and stabilized by a particular within it, authority, and this process was played out essentially in the individual and on the concrete level of the family. It formed the “germ-cell” [Keimzelle] of bourgeois culture, which lived on through it as much as authority did. This dialectical whole of universality, particularity, and individuality proves now to be a unity of antagonistic forces.15 The explosive moment of culture now stands out more than the cohesive.16

In the passage of the Logic Horkheimer cites, §164, Hegel defines the concept as “what is utterly concrete since the negative unity with itself (...) itself makes up its relation to itself,” since the ‘abstraction’ (for Hegel, always an ‘isolation’) of any of its three moments from one another—universality as simple identity, particularity as difference, and individuality as ground—leads only to rediscovering the “inseparability of the moments in their difference”: “Since, however, their identity is posited in the concept, each of its moments can immediately be grasped only on the basis of and with the others.”17 The universal is ‘identical’ with itself, but only because it is identical with itself whether instantiated in particular or individual; the particular is the differentiated, but only has determinacy as an individual that is universal in itself as a distinct ‘kind’ or ‘type’; the individual as subject is the ground which, as substantial, exemplifies the universal and particular (genus and species). Understood as the negative unity of these three moments, “the concept” for Hegel is what enables us to identify the abstract representations we ordinarily call “concepts”—e.g., “human being, house, animal, and so forth”—as abstractions, precisely because they isolate the moment of universality (simple identity) from the moments of particularity (differentiation) and individuality (ground of realization).18 The ‘movement’ of the concept only begins, in short, when the thinker experiences the lack of identity between an abstract concept and its object, resulting in the effort to develop a concrete concept capable of comprehending the discrepancy of the initial, abstract concept and its object,19 which implicates the thinker herself, and her contribution to the process of concept-formation, as well: “as soon as science bears in mind the subject's share in the construction of concepts, it incorporates into itself a consciousness of its own dialectic.”20

In a certain sense, this problem is inherent to any science of society in the double sense of the genitive: the identity and difference of the object of inquiry and the inquiring subject in the social sciences. Crucially, “the subject-object relation is not accurately described by the picture of two fixed realities which are conceptually fully transparent and move towards each other (...), in what we call objective, subjective factors are at work; and in what we call subjective, objective factors are at work.”21 Particularly in the case of social science, given “the direction of the process of abstraction or discovery, by which knowledge of the underlying structure is obtained, itself belongs to a particular historical situation; that is, it is the product of a dialectical process which can never be broken down into neatly separable subjective and objective elements.”22 This is the basic determination of a dialectical process as such:

A dialectical process is negatively characterized by the fact that it is not to be conceived as the result of individual unchanging factors. To put it positively, its elements continuously change in relation to each other within the process, so that they are not even to be radically distinguished from each other.23

As Adorno explains in his late Hegel excursus, Hegel: Three Studies (1963), this experience of the lack of identity between concept and object which underlies concept-formation proper is the historical experience of a historical subject—namely, the experience of an antagonistic social totality (“divided but nevertheless united… society becomes a totality only by virtue of its contradictions”)24 which gives concept-formation a unique character of discontinuous development through contradiction, “a kind of permanent explosion ignited by the contact of extremes,” as dialectic “links the general concept and the a-conceptual (...) each in itself, to its opposite.”25 The concept is formed dialectically, in the movement whereby the unity of opposites can be comprehended by determining the process by which they transform into one another, and capitalist society is nothing if not dialectical:

In its mystified form, the dialectic became the fashion in Germany, because it seemed to transfigure and glorify what exists. In its rational form it is a scandal and an abomination to the bourgeoisie and its doctrinaire spokesmen, because it includes in its positive understanding of what exists a simultaneous recognition of its negation, its inevitable destruction; because it regards every historically developed form as being in a fluid state, in motion, and therefore grasps its transient aspect as well; and because it does not let itself be impressed by anything, being in its very essence critical and revolutionary. The fact that the movement of capitalist society is full of contradictions impresses itself most strikingly on the practical bourgeois in the changes of the periodic cycle through which modern industry passes, the summit of which is the general crisis. That crisis is once again approaching, although as yet it is only in its preliminary stages, and by the universality of its field of action and the intensity of its impact it will drum dialectics even into the heads of the upstarts in charge of the new Holy Prussian-German Empire.

—Marx “Postface to the Second Edition” [1/24/1873].26

Horkheimer’s letters on “Science and Social Need” individuate the crisis internal to the sciences by conscious exploration of the “agon of the middle where individuals confront themselves and each other as particular and as universal”;27 the dispute between Horkheimer and Burri is staged in the middle of the “contradiction (...) between human beings with their needs and capacities and the society that they bring forth” and can only be overcome “in the real historical struggle between the individuals who represent those needs and capacities, i.e., the universality, and those others who represent their ossified forms, i.e., particular interests.”28 In the first moment, the crisis is concretized on the level of universality: a crisis of modern society as a whole. ‘The present crisis’—what the ISR core will later call ‘The Collapse of German Democracy and the Rise of National Socialism’—is singled out as a qualitative break in modern society which has put humanity and social science to the test, but is also only intelligible as a repetition of ‘the greatest disasters in the course of history,’ as unique of a danger as each of the unaddressed crises in the sequence before it. In the second moment, the crisis is concretized on the level of particularity: a crisis of social science as an institution. Social science is singled out among the other “institutions of the middle,”29 struggling against other social powers for more social power, but also against the struggle itself, since social science risks its scientific legitimacy to the extent it serves social authority, and risks its social value to the extent it claims apolitical, scientific purity.

This is “‘the double danger’ of what it is to succumb either to worldly or to otherworldly authority,” appealing to a relatively transcendent, a-political authority for science would only be to “liberate [oneself] from one dominion (…) to submit to another.”30 In the act of “bearing a rational ideal aloft,” the scientist is “at the same time isolated from ideological reconfiguration which may be legitimized, ex silentio, (...) in unassuming legal and social identifications.”31 Like any other institution of the middle, social science stages and restages the conflict of interest between universal ‘social need’, the particular interests of ‘science’, and the intentions of the individual scientist: the ars politica of negotiating the aporetic “and” in “Science and Social Need,” institutional politics of a-political social-scientific inquiry.32 Unlike any other institution of the middle, however, social science is also supposed to understand the predicament it shares with the other institutions it contests: “Classic sociological authorship is not ultimately nervous about its scientific credentials but about its circularity, its foundations: how to gain a perspective on, to criticize, the law which bestows its own form (...) without collusion in that rationality (...) yet without ontologizing irrationality—violence.”33 Horkheimer demonstrates with the case of Auguste Comte:

The reason why Auguste Comte's theory of the three stages through which every society of its nature passes must today be rejected is not that the attempt to comprehend great ages of mankind in as unitary a way as possible was a mistaken one. The reason is that the yardstick applied to history was rather extrinsic and derived from an unsatisfactory philosophy. Comte's procedure suffers especially from the absolutizing of a particular stage in natural science or rather from a questionable interpretation of the natural science of his day. His static and formalistic conception of law makes his whole theory appear relatively arbitrary and unconstructive. The physicist in his researches may justly prescind from the historical process. But we expect the philosopher of history and the sociologist to be able to show how their individual theories and concept formations and, in general, every step they take are grounded in the problematic of their own time. Comte, Spencer, and many of their successors are unconscious of these connections and even deny them in their conscious views of science. It is this that makes their periodizations rigid and inconsistent.34

In the third moment, the crisis is concretized on the level of individuality: a crisis of authority in authorship.35 The crisis is presented as a process of inversion in which each of the author’s intentions or meanings “is equally implicated in the meaning against which it is defined; infected with institutions it seeks to eschew: individual inwardness inverted into the ruthlessness of social institutions, or lack of inwardness colluding in new tyrannies.”36 In Horkheimer’s own words: “Whatever seeks to extend itself under domination runs the danger of reproducing it.”37 As he elaborates in “The Social Function of Philosophy” (1940):

Rationalism in details can readily go with a general irrationalism. Actions of individuals, correctly regarded as reasonable and useful in daily life, may spell waste and even destruction for society. That is why in periods like ours, we must remember that the best will to create something useful may result in its opposite, simply because it is blind to what lies beyond the limits of its scientific specialty or profession, because it focuses on what is nearest at hand and misconstrues its true nature, for the latter can be revealed only in the larger context. In the New Testament, “They know not what they do” refers only to evildoers. If these words are not to apply to all mankind, thought must not be merely confined within the special sciences and to the practical learning of the professions, thought which investigates the material and intellectual presuppositions that are usually taken for granted, thought which infuses with human purpose those relationships of daily life that are almost blindly created and maintained.38

In The Broken Middle (1992), Gillian Rose calls this the agon of authorship. By reflexively assuming the ‘agon of the middle’ (“where individuals confront themselves and each other as particular and as universal”), the author’s method of presentation [Darstellungsweise] is transformed: in form and content, style and method, the composition becomes a demonstration that the author “knows [their work] to be prone to the historical inversions it explores, when authority is object and subject of authorship.”39 This assumption of the agon is evident in Horkheimer’s inaugural address as director of the ISR, “The Present Situation of Social Philosophy and the Tasks of an Institute for Social Research” (1931), a speech devoted to introducing the programmatic “idea of a continuous, dialectical penetration and development of philosophical theory and specialized scientific praxis”—viz., “to do what all true researchers have always done: namely, to pursue their larger philosophical questions on the basis of the most precise scientific methods, to revise and refine their questions in the course of their substantive work, and to develop new methods without losing sight of the larger context”—which concludes with the remark: “This lecture has thus become symbolic of the peculiar difficulty of social philosophy—the difficulty concerning the interpenetration of general and particular, of theoretical design and individual experience.”40

In Horkheimer’s own writing, then, the self-reflexivity characteristic of the agon of authorship is shown by the tendency for each text to ‘become symbolic of the particular difficulty’ it seeks to comprehend, but to do so in a way that, if successful, proves essential for the problem’s comprehension. This is true of the letters to Burri as well, which are communiques of a “crisis of communication” in which “the form and drama” of Horkheimer’s response is “shown to yield a reflexivity which knows that it is bound” to each term of the problem “witnessed and investigated.”41 The integrity of Horkheimer’s response is not in his ambivalence—in classical dialectical idiom, the unity of opposites—but in his equivocation: “‘Mediation’ is equivocal, for it suggests simultaneously the relation between the two and the result of the relation, that in which the two relate themselves to each other as well as the two that related themselves to each other.”42 When unreflected, ambivalence—or the dialectical reversal of opposites into one another—is often vicious and makes vicious those who are caught in its reversals.43 The viciousness of ambivalence lies in failing to appreciate the “dialectical character of the self-interpretation of contemporary humanity,”44 one which is required by the dialectical structural dynamic of capitalist social production and reproduction. This is the sense in which the critique of political economy remains a ‘philosophical’ practice: its content is the reversal of concepts of economic phenomena into their opposites in the course of their fulfillment—fair exchange becomes an intensification of social injustice, free economy becomes monopolistic control, labor which produces social wealth becomes a relation which arrests production, the reproduction of society itself becomes the immiseration of the people who comprise it—and the “dynamic motif” of the critique of political economy is supplied by its comprehension of these reversals, focusing less on the refinement of its predictions of recurrent social events than on reflecting “the historical course of society as a whole.”45 As long as dialectical ambivalence remains uncomprehended—that is, as long as the dualisms, antinomies, oppositions, contradictions, or diremptions in our thinking have not been restored to their context in the antagonisms of our shared political history—it “demands the gratuity of being mended in origin and in perpetuity” in a “cyclical repetition” of attempted overcomings which, because they are forced, reproduce the ambivalence we were driven to overcome by our confusion.46 In the uncomprehended ambivalence of authority, Horkheimer writes, asserts itself in the attitude towards theoretical ideas in which “matter-of-factness” in the dismissal of theory as such provokes a “fetishism of ideas” whenever theory is approached:

Today ideas are approached with a sullen seriousness; each as soon as it appears is regarded as either a ready-made prescription that will cure society or as a poison that will destroy it. All the ambivalent traits of obedience assert themselves in the attitude to ideas. People desire to submit to them or to rebel against them, as if they were gods. Ideas begin by playing the role of professional guides, and end as authorities and Führers. Whoever articulates them is regarded as a prophet or a heretic, as an object to be adored by the masses or as a prey to be hunted by the Gestapo. This taking of ideas only as verdicts, directives, signals, characterizes the enfeebled man of today. Long before the era of the Gestapo, his intellectual function had been reduced to statements of fact. The movement of thought stops short at slogans, diagnoses and prognoses. Every man is classified: bourgeois, communist, fascist, Jew, alien or “one of us.” And this determines the attitude once and for all. According to such patterns, dependent masses and dependable sages throughout world history have always thought. They have been united under “ideas,” mental products that have become fetishes. Thinking, faithful to itself, in contrast to this, knows itself at any moment to be a whole and to be uncompleted. It is less like a sentence spoken by a judge than like the prematurely interrupted last words of a condemned man. The latter looks upon things under a different impulsion than that of dominating them.47

‘Thinking faithful to itself’ is even defined equivocally, as ‘what knows itself at any moment to be a whole and to be uncompleted.’ This is what Rose calls “alertness to implication,”48 or the “unsettled and unsettling approach, which is not a ‘position’ because it will not posit anything, and refuses any beginning or end, (...) without offering any new security, neither individual nor collective.”49 Sustaining the ‘agon’ requires a vigilant, self-conscious practice of refusing oneself the temptations of escape into individual inwardness (authenticity of the singular or outsider), local community (organic communitarianism or total identification with a political faction), and easy universality (empty humanism, formal equality).50 For the social theorist in particular, this means refusing oneself the temptations of false transcendence and false immediacy, of demanding denial of the world or forcing an identification with it: “Agon of authorship here means in argument both to recommend struggle and to struggle daily against this culture, and discursively to comprehend it: to oppose it and to let it be.”51 In “The Philosophy of Absolute Concentration” (1938), Horkheimer responds to the criticism that his work reductively denies the transcendent power of self-immanent thought that ought to elevate thinking above its historical-material presuppositions:

Against the Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung, [Siegfried] Marck levels the accusation that, according to its conception, all philosophical and scientific categories are "defined by their interconnection with the human labor- and production-process. However one’s search for justifications for this demand in the subject matter itself [die Sache selbst] in Horkheimer’s work—that is, for the immanent laws of philosophizing and the analysis of temporal categories—will end in vain.” Even if this does not quite hit on our intention, we still think that philosophy which calls itself political has long since turned into the critique of political economy. [Philosophy] either unmasks the historical situation or falls to its aesthetic epigones. In the immanence of the social relations of monopoly capitalism, the immanent-transcendent treatment of freedom cannot be held onto: it is too transcendent to them. Philosophical anthropology must become a denunciatory physiognomy.

‘Thinking faithful to itself’ renounces its claim to autonomy from the social dynamics from which it arose; ‘thinking faithful to itself’ demands the refusal of transcendence—even into self-immanent thought—beyond this society for the sake of the integrity of its opposition to the same, setting the theorists faithful to thinking itself into conscious opposition with themselves.

The unity of the social forces from which liberation is expected is—in Hegel’s sense—at the same time their distinction; this unity exists only as a conflict which constantly threatens the subjects caught up in it. This is particularly evident in the person of the theorist; his critique is aggressive not only to the conscious apologists of that which exists, but just as much towards diversionary, conformist, or utopian tendencies within his own ranks.52

Postscript: Texts from the Studien (1936).

The core members of the ISR have often been criticized for their refusal to abandon the Studien in exile: “They merely intensified [the scientific] activity they had practiced even in ‘normal’ times.”53 Yet, the Studien itself is a document of exile in both form and content. In a letter to Paul L. Landsberg—student of Max Scheler’s ‘philosophical anthropology,’ former colleague, and fellow exile—dated November 22nd, 1934, Horkheimer explains the project, hoping to recruit Landsberg after the latter expressed interest from exile in Spain:

You will see from these questionnaires that we are primarily interested in two sets of problems:

Which influences are decisive for the maintenance or the loss of paternal authority; in what way is the moment that absolutely establishes the authority that the father (or the mother) deserves weakened or overcome by other factors such as genetic disposition, custom, religion, the number of children, and so on; and how are these relationships modified in terms of social group, country, social class?

What effect does family upbringing rigidly focused on paternal authority have versus character development influenced more by the mother or by other factors?

I don’t have to tell you that the questionnaires are only one small part of our research methodology. At least as important are monographs about already extant scholarship, specific sociological studies in situ, and various kinds of psychological studies. And what you could do in terms of an investigation of the Spanish conditions you mentioned would be valuable to us. …54

Condensing the results of preliminary research on relevant materials collected in the Erich Fromm archive, J.E. Morain (2024) demonstrates that the Studien project, though frustrated in execution and compromised in form by these same conditions, was originally conceived as “a synthetic work which [would] not merely report on the research of the Institute but forge this research into a systematic whole structured and presented on the basis of certain fundamental categories from Marxism.”55 Though the discrepancy between the conception and publication of the Studien is emblematic of both the conditions under which it was produced and the “esoteric form of communication”56 the early critical theorists adopted in response to these conditions, it was a singular achievement: both because it was the single report (besides some ‘reports’ in the ZfS) the ISR would publish on its collaborative research activities for several decades and because it was intended to serve as a preliminary model of the kind of interdisciplinary inquiry the ISR had sought since Horkheimer first assumed directorship.57 Yet, Horkheimer opens his 1935 “Foreword” to the Studien with the confession: “the results […] are incomplete in more than one respect.” (Postscript [B.]) The letters to Burri on “Science and Social Need” (1934) enable us to situate the research program of the ISR as a whole within the unfolding of the crisis—but one that, according to the content of the Studien themselves, long preceded the events of 1933 that finally forced its members into exile. Horkheimer’s reply to Burri amounts to the refusal under fascism ascendant to forego scientific analysis and critical reflection on the society from which fascism ascended. It shouldn’t be surprising that Horkheimer is able to, with minor revisions, revise his theoretical essay for the Studien a decade later under the title “The Crisis of the Family (ca. 1947)”—there’s no school like that of the bourgeois family “for inculcating the authoritarian behavior characteristics of this society.”

Contents.

A. [Excerpts] International Institute of Social Research: A Short Description of its History and Aims (1935).

B. Foreword (1935)—Max Horkheimer.

C. Communique from an Expert (1936)—Karl Landauer.

D. Sketch of a Resumé for the Authority Volume (1937?)—Julian Gumperz.

A. [Excerpts] International Institute of Social Research: A Short Description of its History and Aims (1935).

[International Institute of Social Research: A short Description of Its History and Aims, New York 1935.]58

INTRODUCTORY NOTE.

As social and economic crises recur and become more gripping, the social sciences are assuming greater importance for the reorganization of modern society in the sense of an adaptation of the social processes to the growing needs of humanity. To contribute to this task, the social sciences must examine the general tendencies of these processes in conjunction with the practical problems. For this purpose, not only far reaching empirical knowledge is essential, but also the application of the correct theoretical and methodological principles. The Institute considers therefore the European philosophy of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as important for the theory of society as are political economy and statistics. The economic and technical factors of social processes interact inextricably with cultural and psychological factors. It is important to be able to understand this reciprocity and in keeping with this need, the social sciences try to comprehend, for instance, how economic development affects the cultural aspects of life and further how the economic foundations themselves are in turn affected. It is, therefore, necessary to combine economics, sociology, philosophy and psychology for a fruitful approach to the problems of the social sciences. This combination of the various scientific disciplines is accomplished in the Institute, not merely by the simultaneous work of independent scholars, but also by means of a staff of experts who are in continuous cooperation and whose work is based upon common theoretic principles. By means of this type of cooperation, the Institute hopes to contribute to the solution of the problems which face the social sciences today. However, it does not attempt to cover numerous isolated sociological problems nor to develop a new system of sociology, but is concerned primarily with studying a few problems of particular importance for contemporary social thought. […]

§2. COOPERATION OF SCHOLARS OF DIFFERENT SCIENTIFIC DEPARTMENTS IN ORDER TO INVESTIGATE SPECIAL SOCIOLOGICAL PROBLEMS

The problem actually chosen for this collective work (Kollektivarbeit) concerns the structure and functions of authority in the family in present day society. This problem seems to afford a useful approach to one of the central problems of the Institute, the interaction between economic and psychological forces in the social process. Obedience to authority, which is not only embodied in persons, but also in tradition, in mores, in law, in ideas, etc., is looked upon as one of the key attitudes in the functioning of society and one of the most important character traits produced in the family. The degree and quality of authority in the family are of decisive importance in the structure of society. Here, the Institute has felt, collective work may be fruitful, provided the problem be attacked empirically with methodological thoroughness. The problem is approached from the economic, sociological, philosophical and psychological angles by various collaborators of the Institute who try by frequent discussions to gain further insight on this process into interacting forces. A number of investigations concerning this problem have been conducted in Europe (Switzerland, Austria, France and England). Among the major ones were those concerning the influence of the depression on family life, the attitude of European youth towards authority and the family, the opinions of teachers, clergymen, judges, etc., concerning the attitude of youth towards authority, and other problems. A number of special studies concerning such questions as that of sexual freedom in the youth movement, the history of authority in the family in connection with different types of society, the legal relations of the members of families in different countries, and others have been completed. This collective work was planned two years ago, but because of the closing of the Institute the practical organization had been delayed until the middle of 1933. The New York Branch of the Institute will devote itself for the present especially to the problem of authority in the American family, utilizing existing research and supplementing it when necessary by new research and experimentation.

B. Foreword (1935)—Max Horkheimer.

The publication of these studies serves the purpose of providing insight into the progress of a common project, the results of which are incomplete in more than one respect.59 On the one hand, the true significance of the complex of questions to which the investigations refer can only be unlocked in the comprehensive theory of social life with which they are interwoven; on the other, some of the research is still ongoing, or, indeed, even just beginning. The report before you on the activities of the ISR in this area bears, therefore, an essentially programmatic character. Above all, it is meant to mark out the field that our social-scientific working group is to explore in the next few years. The Institute’s other undertakings include studies on planned economy, research by individual members on special problems, such as the theory of economic cycles and crises, the economy and society of China, questions of social-philosophical principles, and, finally, the publication of a journal covering the whole expanse of social research. As with these endeavors, the Institute’s investigations into authority and the family have suffered under the conditions of our time. The provisional and fragmentary shape of this project, to which this book bears witness, is to a large extent due to these same circumstances. During the last few years of research, the members of our group who contributed to the project have only been able to devote a part of their time to it. That the project has been realized to this extent is due not only to the far-sightedness of our patrons, but also to a number of scientific institutions which have shown us cultural solidarity. To the Centre de Documentation of the Ecole Normale Supérieure in Paris and to Columbia University in New York, we owe the deepest thanks; their hospitality has made it possible for the Institute to realize its work to such a great extent.

The choice of the theme “Authority and Family” is grounded in certain theoretical notions. For several years now, one of the tasks of the Institute has been researching the connection between the various areas of material and intellectual culture.60 It is not merely a matter of investigating how changes in one of these areas of social life affects the others, but, on an even more fundamental level, one of investigating how the various spheres of culture are continuously renewed and related to one another in a way that is vital to society. The more we analyzed the significance of political, moral, and religious views in modern times, the more clearly “authority” emerged as the decisive factor. One of the most important functions of culture to date is the strengthening of the belief that there must always be someone on top and someone at the bottom, and that the latter’s obedience to the former is necessary. An understanding of the interplay between the individual spheres of culture without in-depth consideration of this moment appears to us out of the question. Among all the social institutions which make individuals receptive to authority, the family ranks first. Not only does the individual first experience the influence of the powers of cultural life within its circumference, such that their conception of the spiritual content of culture and its role in their psychic life is essentially determined through the family as a medium, but the patriarchal structure of the family in modern times itself acts as a decisive preparation for the recognition the individual is supposed to offer social authority later in life. The great civilizing works of the bourgeois age are products of a specific form of human cooperation, to which the constant renewal of the family has made an important contribution by education into authority. Of course, the family does not present a final and independent dimension of social life; rather it is integrated with the development of society as a whole and changes continuously. It is perpetually generated from the same social relations it helps to continue and consolidate. These studies serve as an attempt to comprehend and present this process of social interaction. They essentially relate to the European family as it has developed in the course of the last few centuries. Future studies from the Institute will be devoted to the American family; the family in the Soviet Union belongs to a different historical and social structure. Here, the topic is the bourgeois family and its relationship to authority.

The problem itself, as well as the mode in which we pursued it, arose from seminar-style discussions at the Institute and, therefore, do not belong to any one member of our group alone. After our preliminary studies had shown that this theme was both theoretically significant and could be addressed using certain promising empirical methods, we made a group effort to “re-fashion the questions in the course of working on the object, to make them more precise, to devise new methods, and yet never lose sight of the bigger picture.”61 The constant participants in the discussions, in addition to the editor, were the psychologist Erich Fromm, the pedagogue Leo Löwenthal, the philosopher Herbert Marcuse, and the economic historian Karl August Wittfogel. Andreas Sternheim, the head of the Geneva office, played an outstanding role in the preparation of the entire Enquêtenarbeit. Though the first section of this study was edited primarily by the editor, the second by E. Fromm, and the third by L. Löwenthal, the individual articles within the volume were collected on the basis of a common plan; the principles of selection and editorial decisions were also the result of group discussions.

The presentation of the problem, as it arises in connection with the research still in progress, forms the content of the first section. The orienting thoughts for this section were developed through continuous engagement with the materials contained in the second and third sections of the study, and on the grounds of a thorough survey of the available literature on the topic. The first section is divided into three studies. The first, the general division (der allgemeine Teil), attempts to provide an overview of the problem as a whole as it presents itself to us today; in connection with this, the psychological study deals with the psychic mechanisms that work towards the formation of the authoritarian character.62 The historical study essay which follows does not strive for a complete intellectual history of any of the religious and philosophical authors under discussion, but only discusses their theories with regard to our substantive interests. Though the first two contributions do not expressly refer to them, the reader will nevertheless discern how much they owe to these historical studies. A reproduction of our work as a whole in this area would have required a second, separate volume of its own. The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries had to be set aside completely, which is a serious shortcoming, particularly with regard to the work of Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau. —Friedrich Pollock drafted an essay on fundamental economic principles for the first section, but due to his leadership and administrative responsibilities in Institute affairs—not to mention his active participation work on the scientific preliminaries for this volume—this article is not yet completed.

The second section reports on the Enquêten conducted by the Institute insofar as they are linked with the Studien über Autorität und Familie. As indicated in the text above, American social research has served us as a model to a large extent in this section.63 However, since we have little scientific experience in this this area, in addition to many the difficulties encountered in responding to such questionnaires in Europe, the surveys we have undertaken thus far are to a particularly high degree of an experimental character. Nowhere have we drawn generalized conclusions from the results; the surveys were not thought of as means of obtaining conclusive statistics; [rather,] they were meant to keep us in touch with the facts of daily life and, in any event, prevent us from making hypotheses alien to this world. Above all, however, they have been specified for the sake of making fruitful type-formation possible; the characterological attitude towards authority in the state and society, the forms of disruption of familial authority in crisis, the conditions and consequences of more strict or more lenient authority at home, the prevailing public views of the meaning of education, and many other phenomena are to be typologically characterized on the basis of general Enquêten and researched further through individual surveys. The preliminary results have not yet been documented enough empirically for us to attempt to communicate them in a separate, summary essay. However, our assumption that a report on the history, the present state, and the preliminary results of our Enquêtenarbeit, as it is now presented in the second section of this volume, could offer some stimulus for further research on this theme and, more crucially, further developments in the methodology of such investigations—as well as the hope for positive critique—encouraged an initial presentation of our experiments. The Enquêten concerning the middle class and transformations in sexual morality were another consideration in favor of our making a brief report. A portion of the material yielded in this research is not accessible to us under present conditions, and may even have been lost forever. On the other hand, however, these initial experiments with questionnaires determined our later undertakings in many respects, and, in some places, influenced the explanations provided in the first section. — Through our branch in New York, it will be possible for us to learn and apply the methods of inquiry which are practiced in America, and which are more developed than those in Europe.

The disproportion between the space available in the publication as a whole and the scientific material available to us was particularly disconcerting with regard to the third section. This section brings together individual studies which the Institute had commissioned scholars in various branches of science to undertake in connection with the problem of Autorität und Familie. Having to choose to print only a few particularly important contributions in full, we nevertheless opted for a middle path and have shortened many of the essays or presented them in abstracts, so that most of them could be mentioned. The third section—the content of which, despite the intrinsic significance of its individual accomplishments will be of essential benefit to us in the course of our work as a whole, especially in the future—is primarily intended to provide an overview of this aspect of our collective [scientific] activities. The research assignments of the Institute, on the basis of which the majority of these contributions were written, were issued when Institute members considered it necessary to address certain individual questions during their ongoing discussions. Therefore, most of these reports on the literature of various subjects and countries, the monographs on seemingly remote problems, were not originally destined for publication. They were supposed to provide expert instruction and rapid orientation for members of the Institute and, without any explicit reference being made to them, constitute aids, evidence, and explanations of the essays in the first section. A number of these scientific enquiries are the result of extensive correspondence between the respective specialist and the Institute; after an initial report on the theme had been received, the report was expanded and more precisely determined on the basis of new requests. There are, therefore, two or three different versions of some of the contributions. Some works meant for this section have not been mentioned because they have already been published in the Institute’s journal;64 others will appear there in the future.

This volume is regarded as a preliminary communication, to be followed by others at a later stage of the investigation; for this reason, the bibliographical materials collected by the Institute have not at present been included as an appendix. While it was more important here to make the problem apparent to its widest extent, the Institute will in future principally concentrate on the collection and analysis of empirical materials which are as comprehensive as possible. But we remain convinced that the direction in which we have started, i.e. continuous collaboration between representatives of various disciplines, and a fusion of constructive and empirical procedures, is justified by the present state of scientific knowledge.The problem of authority and the family is not the center of the theory of society, but it may deserve greater attention than it has received thus far. As far as the family’s significance for authority in present-day society is concerned, it has formed a mediating factor between material and intellectual culture and has played an indispensable role in the regular course and renewal of life in general in its given historical form.

New York, April 1935. — Max Horkheimer.

C. Communique from an Expert (1936)—Karl Landauer.

The following report65 by the psychoanalyst Dr. Karl Landauer (Amsterdam) is but one of a whole series of statements that have been sent to us by doctors and sociologists who, having been made aware of the Institute's investigations into authority and family, expressed interest in this investigation through active collaboration. We include this interesting statement here because it deals primarily with the problem of sexual morality.

My experiences relate to a number of Holländer, residing at present in and around Amsterdam or The Hague, but originating from various parts of the country. All of them belong to well-educated social circles. Only a very few come from the proletariat or lower middle class, a few of them are nearly haute bourgeoisie; the overwhelming majority are upper middle class (intellectuals, merchants, members of the liberal professions or senior civil servants). In Holland, this class strata is still characterized by a relatively high level of security. It is only through the ever-intensifying crisis that such secure standing has begun to falter here as well. In the main, we encounter a very similar relation within social relationships to that in Germany around the turn of the century, and, in accordance with similar external relations, certain far-reaching analogues of a psychological nature, such that in some respects one feels as if one has been transported back in time. On the other hand, however, there is an admirable openness to the most advanced technology, characterized in schools by a strong emphasis on arithmetic and mathematics, in transport by extensive motorization and generous construction of roads and especially bridges, and in the medical practice, for example, by the most refined development of methods of investigation.

The first thing that struck me was, in contrast to my German experience, the completely different attitude towards the problem of premarital chastity, both for the women and, particularly, for men. I could hardly believe my own ears when a colleague told me shortly after my arrival that around half of all medical practitioners are still chaste when they marry. This is, in any case, a much greater number than one might find in contemporary Germany, Austria, England, America, France, Italy, and Scandinavia. Of course, medical practitioners—we cannot say doctors, because a large portion are still students—often marry around the age of 22 or 23. The fact they tend to marry so early is therefore a very important phenomenon. The young people are still thoroughly socially dependent personalities when they marry. In material terms, they are still part of the parental family, and often remain so for a long time, which accounts for the very close connection within these extended Dutch families: authorities in the extended family have a say in all essential external decisions, such as housing and furnishings, questions of further professional education, settling down and becoming fully independent, and, in recent years, even the question of offspring. It is not rare for this dependence to last a lifetime, as doctors often remain connected to hospitals, counseling centers, and similar non-profit organizations, from which they do receive a salary—which is often very small—but, above all, prestige in the eyes of their clientele. However, they owe these positions not only to their own abilities, but very often also to the influence of their family over boards of trustees, or to a given church or religious denomination. Psychologically, where the experience of the individual is concerned, their influence derives from family authority.

This material power of the family is expressed in a rather characteristic fact: anyone in Holland who wants to marry before the age of thirty, must, in addition to the usual documentation, also provide a declaration from their parents that the latter approve of the marriage. Admittedly, it is not difficult (or so I have heard) to replace this declaration with a court order if the declaration is refused. But the very fact that such a declaration must be obtained by flattery or fought for heightens the significance of the parents, even for 20-30 year olds. That this legal requirement has not long since been buried shows how deeply the authority of parents is anchored among the general population. On the other hand, the declaration creates a moral obligation on the part of the parents to provide for the young couple. In the event one side of the family cannot provide sufficient capital to guarantee material security once and for all, it becomes necessary for the heads of the two families to negotiate a set monthly amount to be paid by each. Thus, not only the two spouses, but also the two families, must come to an agreement. The declaration of consent does not have the significance of a one-time laissez-faire understanding, but a relatively permanent commitment.

The best illustration of this relation is by means of a few examples which I have not seldom encountered myself and which have also been confirmed as typical by a number of my colleagues. A 21-year-old man falls in love with a 20-year-old student at a school ball. On the way home, they kiss and embrace. Then the girl asks: “Are you still pure?” He then confesses guiltily that he was seduced by a married relative when he was 17. To this, the girl replies: well, we must try to get over that. And, since they are now engaged, she asks him to meet her parents the very next day. There, the mother greets him: it is very unfortunate he has not remained chaste, but there is nothing to be done about it—they are engaged. “You did kiss after all.” And the father (a Puritan merchant) demands an interview with the boy’s father. So the boy, with fear and trepidation, must confess to his father (a senior Catholic official). And the fear is not unfounded, for the answer to the marriage-candidate’s message sounds something like: “You rascal, make something of yourself first!” There is nothing the poor sinner can do but relay to the father of the bride the attitude of his own. The family council decides it is best to wait for a while; in the meantime, the bridegroom may dine with the family once a week. Following the meal, the bride and groom may retire to the adjacent room for a cup of tea and some predetermined topics of conversation. It is hardly surprising that such a situation is not exactly love-enhancing. The young man does not know how to break off the unintended engagement. But what can be done about it? In the end, some friends advise the bridegroom to take some life-saving action against his will: the young man strolls through the church fair with two, locally infamous prostitutes on his arm! Thus the engagement comes to an end. Engagement vows are often broken. The number of twice or thrice-engaged people is much, much higher than it was in Germany, for example, where, in the corresponding pre-war social circles, breaking off an engagement was perceived as social degradation. This was grounded on the stronger ideal of chastity for men; such severity on the one side must correspond with greater leniency on the other.

To be seen in public not just with a prostitute, but with a girl in general, and to be seen with her often if she is not one’s fiancee, is still considered unsightly in many social circles today—not so long ago, in the majority of social circles—given the power of family authority, not only among the older generation, but even amongst young people themselves. And thus in Amsterdam student circles, albeit only between friends, serious discussions are held about the possibility of non-purely Platonic relationships with girls. Since getting to know girls directly has been made so difficult, and indeed almost impossible, the imagination is all the more preoccupied with the qualities of the opposite sex. On the one side, love and women are mediated and intellectualized; on the reverse side, the grapes must be soured.

It is clear that when it comes to such difficulties in becoming acquainted, chance plays a large role. When this chance does appear, it often occurs through the figure of one’s friend. For example, a 22-year-old law student became acquainted with his colleague’s sister through the colleague himself. Both were musically inclined, and so, a duet (Quatre-mains) under the supervision of her conservator of the same age arose quite naturally. A shared love of music, but also—and what was of true psychological significance—a shared love of brother and friend, generated an atmosphere of mutual infatuation. The girl’s father, a very wealthy Calvinist factory owner, can afford a poor son-in-law, especially since he is considered to be so talented. And the young man’s father, a Calvinist commercial clerk, happily sends his blessings from the West Indies, which releases him from any further obligation to support his son. While the first case came to a happy, early end thanks to the father’s stubbornness, the second had to be lived through in all of its sad consequences for all parties involved: the two youths were now supposed to live together, not just play the piano together; but that required a rather different kind of match in personalities and facilities. Thus, the woman had to fill the initially small household with love and, as the children came one after the other, show them motherly affection. In this she was lacking, both towards the children and towards the husband. And the man, for his part, had to be not only a capable scholar, but also someone with a great ability to love. When the trifles of the day create endless tensions and difficulties, a sensitive lover of an unpleasant lover could have made up for much that was lacking. But the inhibitions of childhood continued to take their effect on sexual relations after they had married. In matters of love, too, one has to learn from others, from experience, from stories. But this was not possible: no one had lifted the taboo that burdened their sexuality, not even for certain periods of time, as is the case with so-called primitive peoples or what remains for us during Karneval. And thus, for a few short hours of happiness, in which the young pair sought to escape their isolation as sexual beings, they were punished with many years of excruciating marriage. And then came the divorce. This was another impression of great import that my transfer to the Dutch milieu has left me with: the relatively frequent premarital chastity of both partners was offset by a relative frequency of divorces.

In many cases, however, there is no force of equal strength to tear apart the safety net of marriage into which one has stumbled once this situation has been recognized. Frequently, after the first few years of marriage, which is a time of intellectual and often economic dependence, a period of rebellion will follow. Since both partners are lacking in sexual experience, being together is often anything but pleasurable. This cannot be love—the love of which, as a result of congestion, one fashioned an exaggerated representation as a factor of pleasure. No! People murder each other for that kind of love! Such love must first be sought out. Since one cannot do so openly, it is done surreptitiously. And now, after three or four years of a joyless marriage, a secret hunt for pleasure begins. The man suspects it is to be had everywhere: with the wife of a friend, who is also seeking it in her own joyless marriage, with one’s married relatives, with young artists, shopgirls, and prostitutes.

Very often, I have encountered men and women in the second half of their twenties or the first of their thirties who, out of disappointment with a certain love-object, passed through a seemingly objectless period of time in which they consciously sought only pleasure as such—by which one might imagine auto-erotic pleasure. But, in actuality, it is a period of time characterized by hostility to objects. The essential, positive object is one’s own ego. The “successes,” the potency, the craftiness with which an often unconscious revenge is exacted upon one’s partner in pleasure through the release of pent-up aggression—satisfy narcissism.

On multiple occasions I have observed formations reminiscent of small groups: several married couples live together in a tangled ball of yarn. This seems to be due to the impossibility of premarital relations. This is how unconscious homosexual and incestuous longings find their expression. Such longings increase the already powerful feeling of guilt through strong, unconscious contributions. In the above-mentioned case, in which the friend’s sister was married, a frowned-upon exhaust of unconscious feelings of hatred was released against the brother-friend, the instigator of the marriage, whose (homosexual) shadow hung inhibitingly over the whole marriage.

In this connection, I would like to make a remark, with all due reserve, on the frequency with which I came across more or less open or secret prostitution here in the same circles where I’d hardly encountered it in post-war Germany: in addition to the unconscious significance of homosexuality (in young men’s extensive same-sex sociality before marriage), the intellectualization of love and of the romantic partner play an essential part in this. The sanctity of the family and the mother of the children prohibits love-play, the extragenital foreplay and substitute satisfactions which are socially without value; they are only bearable as things of inferior value, and only in secrecy. In Holland, even today, it is not uncommon for there to be 3 or 4 children in one of the social circles described here. It is only very recently the case that children are not always born in the very first years of marriage. Of course, in general, the conscious regulation of fertility only begins after several years of marriage, and only then does marriage begin to not only satisfy the social demand to bring children into the world, but also that of pure sexual pleasure.

What I have described thus far is the background against which the life of those in the so-called educated class strata seems to take place here, and which intrudes unconsciously but decisively even after the last few years and decades have brought changes to the foreground, to consciousness. The economic crisis has shaken the foundational pillars of this view. It has reduced capital. And it was on this very basis, on which the security the older generation offered to the younger once rested, that the morality through which the younger assimilated to the older generation was grounded. Thus, it is no wonder that in student social circles in Amsterdam today, the oft-discussed possibility—as I mentioned above—of erotic relationships with so-called respectable girls has not only changed in character, but even realized. Admittedly, however, this only occurs in secret, such as a student having an affair with the sister of his colleague, but indignantly rejects any suspicion of this suggested by the office secretary. This heightens the inner struggles of the girl, who is caught in a thousand internal conflicts because her brother’s friend and colleague is courting her, although he, like her, is still hampered by his upbringing. How much the times have really changed can be discerned in a statement made by the father, a Protestant senior civil servant, of the young man in this story. Although he doesn’t doubt the innocence of his 23-year-old son, he need not even suspect it would have long since disappeared if the friend could at least be honest with his sister who is almost the same age he is. And so, the father says to his son: “In my youth, I had it better than you. We didn’t even have the same temptations.”

My impression is that the still relatively strict sexual morality I have observed (on an admittedly limited sociological scope) in Dutch group-formations may be seen as a symptom of the continued stability of social authority in most, or all, traditional social institutions. In other countries where sexual morality has become more relaxed, the traditional structure of culture as a whole is also under attack.

D. Sketch of a Resumé for the Authority Volume (1937?)—Julian Gumperz.

Resume-Entwurf zum Autoritätsband (Gumperz) [IX136.a]66

Society and social institutions, whatever metaphysics [has]67 to say about them, imply for any rational investigation of the laws that govern them the conception of a whole, of a unit. In speaking of society we assume, therefore, the existence of certain centripetal forces, the operation of which assures cohesion among the different social institutions and elements. No integrated social body would be able to function were it not for such forces of unification and integration, any more than this earth of ours, with its myriads of component elements, could rotate around the sun as a solid body without the forces of gravitation. Through all times down the ages, within the different social organizations of the various peoples and nations, there have been in operation certain forces that have served as centers of gravity, and that in their ever-changing historical aspects preserved such an essential identity as to make them recognizable in their various manifestations.

Among them, the fact that there always has been a superior and an inferior, and the resultant belief that obedience is a necessity, appears to be one of the most important. Authority and the various social relationships that spring from it are phenomena that can be traced as far back as human history goes. And wherever they are discovered as a ligament in social institutions, they are not restricted to some narrowly delimited field, or to one particular social subdivision, but related to the entire social framework of which they form so important an element.

Now obviously, authority, as well as other social forces, does not remain in continual operation in the same way as gravitation. It has to be produced and reproduced within the living organism of a society that transmits its behavior patterns from one generation to another through well established paths and channels of social action and reaction. Many institutions contribute towards establishing such a web of transmission lines, and among these the family occupies a pivotal place. In it and through it society produces and reproduces the relationships of authority that are essential to its smooth and uninterrupted functioning.

The tools of science are fitted to the particular task that confronts them. Wherever the social sciences during the last few decades applied themselves to particular delimited fields of inquiry, or subdivisions of the social whole, they developed tools of research especially adapted to this task, and there can be no doubt that through their statistical and empirical investigations they have enriched our knowledge on a tremendous scale. These social scientists, however, who during this period occupied themselves with the clarification of the sociological conceptions and principles employed in empirical work, could hardly hope to move into the focal point of scientific interest. The preoccupation with matters of immediate statistical applicability during the past thirty or forty years of development in the social sciences also relegated to the background the work of those men who in the earlier days, through their encyclopedic vision, had established systems of social thought which permitted the comprehension of society as an integrated entity.

At the present juncture the need for assembling into a well-ordered whole the disjointed elements of research in the social sciences is felt everywhere, and it is, therefore, understandable that the International Institute of Social Research, which has made such an attempt one of its prime objectives, has selected for its first major undertaking of this kind the problem of authority and the family, which, by its very nature, requires the coordination of the various departments of the social sciences.

The Institute presents its first findings in this field in a volume of approximately 950 pages, published in Paris by the Librairie Félix Alcan. The volume is subdivided into three major sections, the first presenting in three separate essays a theoretical treatment of the subject from the standpoint of social philosophy, psychology, and history. It appears from these contributions that with the emergence of modern society there developed a certain attitude and conception of authority that is characteristic of this particular historical form of society. It is obvious, consequently, that the strengthening of authority relationships at the present time, as evidenced particularly in the totalitarian states that have come into existence, does not signify a decisive break with tradition, and it is pointed out in these essays that this transition has its roots in earlier established authority relationships. This is not contradicted by the fact that earlier periods, especially the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, regarded the belief in authority, the subjection to a superior will, the submergence of independence in thought and action, as contrary to the ideals of their time. Closer inspection shows that these ideals, that the love for liberty and reason, were inextricably intertwined from their very beginnings with their opposites in the realities of life as it existed.

The universal empiricism that made facts the court of last appeal has been a characteristic of this particular attitude towards authority in modern times, The Middle Ages presented relationships of authority in the immediate form of superiority of ruling persons. In modern times they manifest themselves in the belief in unalterable facts as, for instance, the inevitable inequality of wealth.

The psychological chapter deals with these relationships by critically examining Freudian psychology. It attempts to show that modern man in his mental make-up has accepted authority and authority relationships as they exist, from the very beginning, without question and as a matter of course. The historical chapter traces the main currents of thought in regard to this problem as they arose in connection with economic and social change during modern times, and gives a presentation as well as critical analysis of the views of the outstanding representatives of modern thought on this problem. After a perusal of the pages on the theories of the Counter-Revolution in France, or of Pareto, the present emphasis on authority and authoritarian regimes, we find, does not appear to be a retrogression into times preceding modern capitalism, but results from the dynamics of modern society. The role that the specific form of the family in modern times plays in the shaping and forming of authority, and the attitude towards it, is clearly shown in these first essays.

The second major section reports on the results of the empirical researches which were undertaken to determine in this way the influence of the family on the prevailing structure of authority. Two different investigations were undertaken and carried on in Belgium, France, Austria and Switzerland. The first one dealt chiefly with adolescents. The second one canvassed experts who, on account of their practical connection with the problem, were able to render an opinion on it. Physicians, social workers, churchmen, teachers, judges, etc., in different countries replied to the question whether, within the cross-section of families with which they were familiar, the authority of father, mother or other members of the immediate family was decisive for the children, whether the role of woman within the family changed if she worked outside the home, whether strict or lenient discipline in education and training, or training within or without the family, affected the adaptability of the individual to his surroundings, etc.

These investigations on a bigger scale were supplemented by others with less ambitious intentions. For instance, questionnaires were mailed out to physicians asking them about their observations of changes in sexual morality in the post-war period, certain selected homogeneous groups of workers and employees were studied in regard to the problem, and a somewhat larger investigation was initiated in the attempt to establish the influence of unemployment on authority relationships within the family.

The third major section brings together separate studies undertaken by specialists in different branches of learning, in the attempt to throw light upon the problem studied from the viewpoints of the various social sciences. Biological, anthropological, and historical studies, monographs on the legal questions involved, and especially on social insurance laws as they affect the family and the authority relationships in the various countries, contribute to the illumination of the wide implications of the problem under investigation. Bibliographical surveys analyze to what extent and under what auspices the problem has found attention in the sociological literatures of Germany, England, France, Italy and the United States.

The present volume represents only the beginnings of an investigation, and therefore does not present definitive results and recommendations. The International Institute of Social Research publishes this report of its activities as evidence of the work in progress since the organization was compelled to leave its headquarters at the University of Frankfurt in Germany, and to organize a branch office in Geneva, with the assistance of Mr. Albert Thomas, then the director of the International Labor Office. Owing to the fact that the Institute, a privately endowed organization, held most of its funds abroad, and to the hospitality offered by the Sorbonne in Paris and Columbia University in New York, the Institute has been able to continue the work that had been interrupted by political events, and to present the first results in this volume, to a larger audience.

For a more detailed account of the ISR’s first phase of exile, between Geneva-Paris and New York, see Rolf Wiggershaus, The Frankfurt School. Its History, Theories, and Political Significance. Trans. M. Robertson. (Polity 1994), 127-148. For the official communications from state and university authorities notifying Horkheimer of the closure and seizure of the ISR, as well as his personal dismissal, in MHGS Bd. 15 (1995), 101; 111-114.

Quotation from a newspaper clipping cited in Wiggershaus, The Frankfurt School (1994), 128-129.