Dämmerung III: Aphorisms From Dämmerung (1934)

Dispatches in communist counterintelligence from and for times of reaction.

Part III of a series of translations of texts for, from, or contemporaneous with Horkheimer’s Dämmerung. Notizen in Deutschland (1934).

Dämmerung I: Horkheimer's Weimar Journals (ca. 1920-1928)

Dämmerung II: Notes For Dämmerung (1926-1931)

Dämmerung Appendix I: Sketches for a Negative Metaphysics. Herbert Marcuse (ca. 1933)

Translator’s Note.

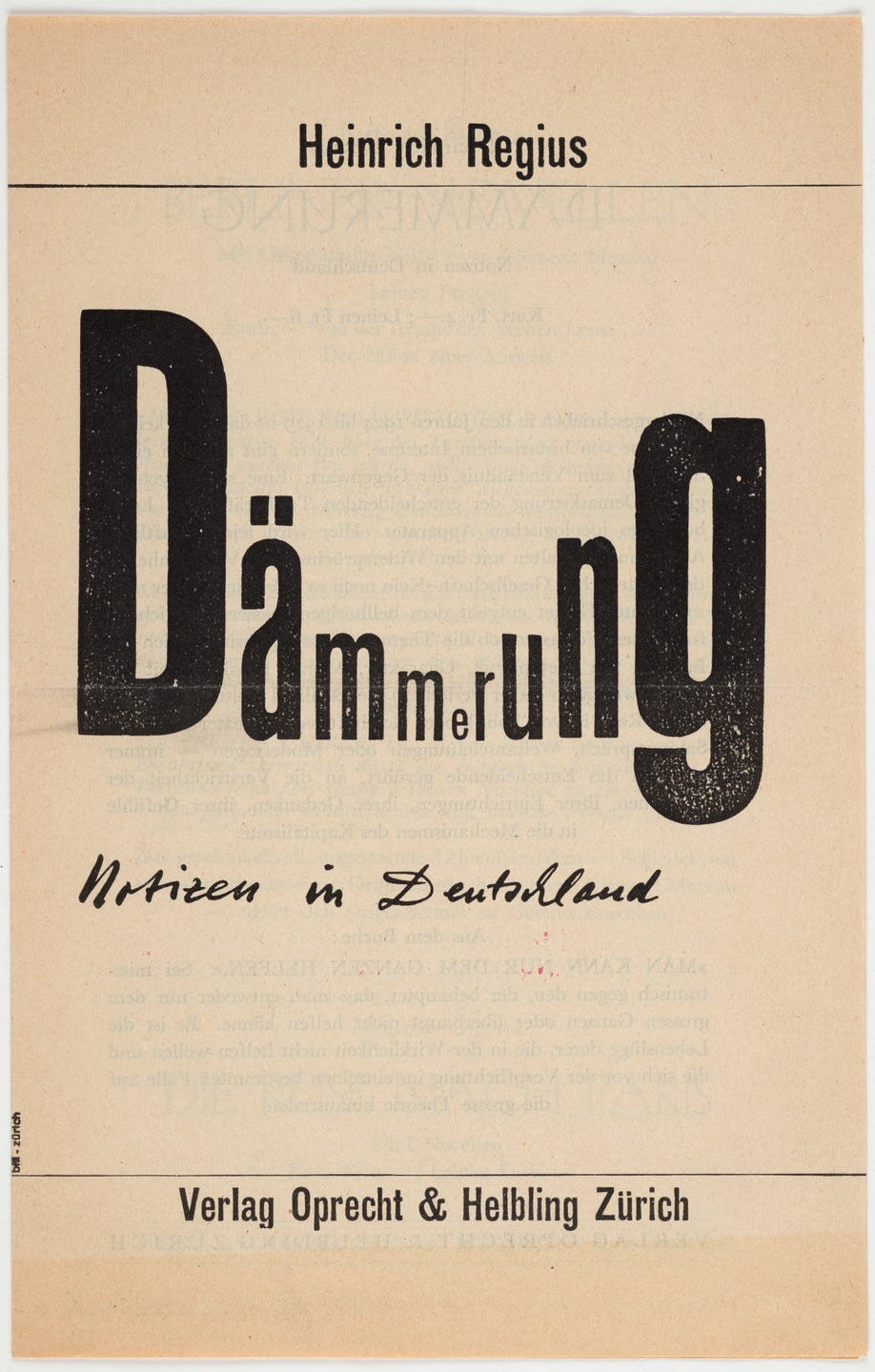

The only book Max Horkheimer (1895-1973) ever wrote—in full, and as a book—was published under the pseudonym of Heinrich Regius through Verlag Oprecht & Helbling in Zurich, Switzerland, in 1934. Dämmerung: Notizen in Deutschland is a collection of aphorisms composed between the years of 1926 and 1931, dispatches in communist counterintelligence from and for times of reaction. Of the 136 aphorisms contained in the original 1934 printing of Dämmerung (and its re-publication in 1974, 1987), only 108 were selected for the sole extant English translation of the text: Dawn and Decline: Notes 1926–1931 and 1950–1969, translated by Michael Shaw (1978). The following collection consists of original translations of the remaining 28 aphorisms, sourced from Horkheimer’s Gesammelte Schriften. Band 2: Philosophische Frühschriften. 1922-1932 (1987), in addition to re-translations (marked with an asterisk) of the two aphorisms which open the text (‘Twilight’ [Dämmerung] and ‘Monadology’) given their significance for an orientation to the text as a whole.

[Any additional re-translations in the future will also be marked with an asterisk. — 4/16/25.]

Contents.

Prefatory Note.

Twilight (Dämmerung).*

Monadology.*

Telltale Hands.

The Partiality of Logic.*

All Beginnings are Difficult.

From the Inside, Out.

The Hotel Porter.

“The work-reddened hand that swings the broom Saturday / On Sunday knows how to give the softest caresses.”

Value-Blindness.

Twofold Rebuke.

Tact.

Metaphysics.*

Degrees of Culture (Bildung).

A Category of the Big Bourgeoisie.

The Perception of a Person.

The Cares of the Philosopher.

Gratitude.

Person as Dowry.

Lies and the Human Sciences.

Peculiarities of the Age.

Character.

Serious Living.

Horror over Child-Murder.

Interests of Profit.

Make Way For The Capable (Freie Bahn dem Tüchtigen).

Human Relations.

On the Distinctions of Age.

‘Suffering Teaches Wisdom’ (Durch Schaden wird man klug).

Double Standard.

On the Relativity of Character.

Waiting.

To Forget.

Note: Three Keys for Reading Dämmerung.

[Excerpts from Gunzelin Schmid Noerr’s “Editorial Afterword” to MHGS, Bd. 2.]1

(1) Marxism as the critique of prevailing forms of consciousness and the objective social relations to which they correspond.

[In these writings,] Horkheimer understands Marxism neither as a new type of philosophy, nor as a new economics, nor even as a new conception of history, but as critique of these forms of consciousness and the objective social relations to which they correspond. It is this conception of Marxism which, among other considerations, is the reason for Horkheimer’s abstinence from “Marxist”-immanent writing. In this, he unmistakably follows the Marxian conceptual figure of abolition through actualization. As a consequence, the critique remains, in a certain respect, consciously external to that which is criticized. Characteristic of this is an aphorism from Dämmerung, [“Metaphysics,”] in which Horkheimer takes issue not so much with the purported truth-content of metaphysics but instead reveals its social function, which he sees as the justification of real misery by looking to the eternal: “I do not know the extent to which the metaphysicians are right—perhaps there is some particularly poignant metaphysical system or fragment out there somewhere. What I do know, however, is that ordinarily metaphysicians are not much impressed by what torments human beings.” Philosophy, as the most developed form of bourgeois consciousness, appears to materialistic critique as aporetic, insofar as it consists largely of mere conceptual exposition or reconstruction of what has actually won out in the course of history thus far. In each case, theoretical problems are shown to have historical-practical origins and, therefore, can only have historical-practical solutions. The critique of ideology recognizes it as a socially anchored power, one in the face of which any adherence to the traditional value-positing claims of philosophy, any purely theoretical or moral objection, can only appear as another weak or over-exaggerated renaissance of metaphysics. Yet, materialistic critique does not dispense with the careful study of both the history and structure of its object. To the contrary—any truly explanatory understanding must not reduce thought to its objective conditions, but delve into each philosophical problematic of substance in detail, in order to develop an interpretation of it against the background of its socio-historical context without surrendering its content. Critique must avoid both: the history of ideas in the manner of the Geisteswissenschaft and vulgar-materialistic reductionism. [...]

(2) Style as method: patterns for the presentation of the universal in the particular.

[…] Horkheimer’s works on the philosophical tradition and the philosophy of his contemporaries which were published during the 1920s and the early 1930s retain a form, despite their relatedness to social-practical interests which serve as a guide for his theory, well within the framework of scholastic, philosophical treatises. This is what Horkheimer escapes, however, in his notes of 1926 through 1931, many of which would appear under the pseudonym of ‘Heinrich Regius’ and the title Dämmerung. Notizen in Deutschland, published in Zurich in 1934. With their aphoristic form they are, as much as the form of the essay, emblematic of Horkheimer’s authorship as a whole; they point forward to the ‘Aufzeichnungen und Entwürfe’ [“Notes and Sketches”] of the Dialektik der Aufklärung […]. In the notes for Dämmerung, Horkheimer presents the universal within the particular. Analysis of the false indirectly renders visible the outline of the true. The primary stylistic elements of this procedure are the metaphor, the example, the concise narrative, the differentiation of things which are alike, and the exhibition of likeness between things which are farthest apart. These stylistic patterns are opposed to systems-thinking, definition, and deduction. The selection of form is grounded in the intention of the critique, which, in addition to bourgeois thinking, is also concerned with the enterprise of conventional philosophy and science as a whole. In their content, the notes for Dämmerung already anticipate the full range of central categories and figures of argumentation found in later critical theory. These notes contain a historically determinate, anthropologically deepened, and culturally broadened analysis of capitalism, bourgeois society, and the forms of consciousness which belong to it. The Notizen, Horkheimer writes in the prefatory note to Dämmerung, “refer repeatedly, [and] critically, to concepts of metaphysics, character, morals, personality, and human value as they were valid for this period of capitalism.” In these notes, he deciphers the ideas of the time and their contradictions as an expression of class society. […]

(3) The historical-materialist perspective: socialism as criterion; illusionless composure.

[…] In adopting such a historical-materialistic perspective, the timelessness of scientific and philosophical claims vanishes, as does the illusory semblance [Schein] of an unchanging human nature and the cultural-universalistic consecration of social values. The criterion of critique is the idea of a rationally organized society wrested from the philosophical tradition. The transition to socialism appears not only historically possible, but even overdue and morally incontestable, yet has no guarantee from any logic immanent to history. Horkheimer is illusionless with respect to any form of quasi-salvation-historical expectation. He is conscious of the “sad discovery” that not even the claim to absoluteness of such illusionlessness permits the derivation of any objective meaningfulness whatsoever. Even this claim is, in the end, as finite as those who advance it. In view of the historical-philosophical skepticism this demands, Horkheimer is all the more insistent that what matters is resolve for the realization of a condition in which hardship and injustice would be eliminated, the organization and the struggle of “human beings resolved for the better.” […]

Woher der düstre Unmut unsrer Zeit,

Der Groll, die Eile, die Zerrissenheit? —

Das Sterben in der Dämmerung ist schuld

An dieser freudenarmen Ungeduld;

Herb ist's, das langersehnte Licht nicht schauen,

Zu Grabe gehn in seinem Morgengrauen.

— Lenau, “Schlußgesang.” Die Albigensier (1842)

Prefatory Note.

This book is out of date. The thoughts it contains are occasional notes made over the years from 1926 to 1931, in Germany. They were recorded during pauses in strenuous work without the author taking the time to polish them. As a result, they are entirely disordered. They contain many repetitions, and even some contradictions. The range of their themes is not without uniformity, however. They refer repeatedly, and critically, to concepts of metaphysics, character, morals, personality, and human value as they were valid for this period of capitalism.

Since they belonged to the time before the final victory of National Socialism, these notes concern a world that is already anachronistic. Problems such as social-democratic cultural politics, bourgeois literature in sympathy with the revolution, and the academic reformation of Marxism formed a spiritual atmosphere which has now disappeared. Nevertheless, the ideas of the author, individualistic in his way of life, may not be wholly without significance for a later time.

Germany, February 1933. — Heinrich Regius

Twilight (Dämmerung).

The more storm-shaken necessary ideologies become, the crueler the means that must be used to protect them. The degree of zeal and terror with which faltering idols are defended shows just how far the twilight has already spread. The intellect [Verstand] of the masses in Europe has grown so great with the expansion of large-scale industry that the most sacred of goods must now be sheltered from it. Whoever defends the latter well will surely secure a career for themselves; woe to the one who speaks the truth in simple words: alongside the general, systematically driven stultification of the mind, the threat of economic ruin, social ostracism, imprisonment, and death prevent the intellect from attacking the highest conceptual means of domination. The imperialism of the great European states has no need to envy the Middle Ages for its woodpiles and witch-pyres; its symbols are protected by a more refined apparatus and more terribly armed guards than the saints of the medieval church. The enemies of the Inquisition turned that twilight into the dawning of a new day; even the twilight of capitalism need not usher in the night of humanity, though it certainly seems to threaten to today.

Monadology.

A philosopher once compared the soul to a house with no windows. Human beings become involved with one another, speak with one another, do business with one another, persecute one another, yet without ever seeing one another. The philosopher then explained these representations human beings have of one another by saying that God has placed an image of others within the soul of each individual, which, in the absence of any external impressions whatsoever, develops over the course of one’s life into consciousness of man and world. But this theory is questionable. The knowledge human beings have of one another does not seem to me to stem from God; rather, these houses do seem to have windows, but such which allow only a small and distorted glimpse of outside events to bleed through. The moment of distortion lies less in the particularities of the sense-organs than in the psychic attitude [seelischen Einstellung]—worried or cheerful, anxious or eager to conquer, cowering or superior, sated or yearning, languid or vigilant—which forms the ground of our lives and against which all our experiences stand out and which gives them their character. Aside from the immediate effects of the compulsion of external fate, this is the ground on which any possibility of understanding one another depends.2

Two images which might serve as emblems [Wahrzeichen] of the general degree of understanding within capitalist society: annoyed at having been called away from playing with his comrades, the child pays a visit to his sick uncle; at the wheel of his new convertible, the Prince of Wales drives past an old woman. I know only one kind of gust which might blow the windows of the houses open wider: shared suffering.

Telltale Hands.

At New Year’s Eve celebrations held in upscale wine bars and the better hotels, a feeling of togetherness, intimacy, and camaraderie prevails among the guests. Despite the ordinariness of such occasions, they recall the harmonious atmosphere which accompanies natural disasters, national holidays, misfortunes, the outbreak of world wars, record-breaking achievements in sport, and so on. The beginning of the New Year is considered a universal human affair, one of those majestic events during which it becomes apparent once again that the distinctions between human beings—above all, that between rich and poor—are in actual fact inconsequential. The intermixing, already tempered on this night by the price differences between various places of entertainment, is, of course, further restricted by the presence of the waiting staff; on the whole, however, a spirit of congeniality prevails, and, by twelve o’clock, all are united in momentous exuberance. At precisely this hour, when the jubilation was at its height, the little clerk, invited by her distinguished friend, spilled wine on her dress. While her face beamed with enthusiasm, reflecting the general frivolity, her hands carried on removing the stain with unconscious zeal. These isolated hands betrayed the whole festive company.

The Partiality of Logic.

When someone drily makes note of an evil, injustice, or cruelty inherent to this social order, they often hear: ‘one must not generalize.’ Counterexamples are provided.

But it is precisely here that the method of counterexample is logically inadmissible. Indeed, the assertion that justice exists somewhere may be rendered invalid through the demonstration of a single counterexample, but the reverse is not true. Accusations raised against a prison made hell under a tyrannical warden can never be deprived of their force by a few examples of decency, but the administration of a good warden is belied by a single case of cruelty.

Logic is not independent of its content. In light of the fact that, in actuality, what comes cheap for the privileged part of humanity remains out of reach for the rest, an ‘impartial’ logic would be just as partial as the code of law which is the same for all.

All Beginnings are Difficult.

All beginnings are difficult, and because most only get a chance to begin once, because most are only offered the prospect of a better station in life once, if at all, they make out poorly and remain set in their misery. Anyone who enters a salon without familiarity behaves unseemly, and woe betide anyone who is noticeably eager to be there. The freedom, matter-of-factness, “naturalness” which make someone sympathetic in high social circles are an effect of a certain self-consciousness, usually reserved only for those who have always belonged there and can be sure of remaining. The haute-bourgeoisie identify those with whom they prefer to be around, “nice” people, by their every word. All beginnings are difficult. If one gives an apprentice a job he has seen their assistant accomplish a hundred times, he will do it wrong anyway unless identification with the skilled tradesperson is in his blood, just as identification with good society is in the blood of a gifted con man. One need only hold the lower to the accomplishments of the higher to see him fail. Thus, the established hierarchy is confirmed again and again. The dependent is untalented. This becomes yet more complicated by the fact that beginning is more difficult for everyone as they grow older, and those who were not born into a happier situation or who slid into one young are tainted for life. The self-made-men only prove the rule—but even they are rarer than ever, for the beginning is more difficult than it ever was before.

From the Inside, Out.

The child in the bourgeois family experiences nothing of its conditionality and alterability. It accepts the relations as natural, necessary, eternal; it “fetishizes” the form of the family within and into which it grows. It therefore misses that which is essential about its own existence. Something similar applies to those who have fixed relationships within society. Though certain sections of the working class—there are not nearly as many as one tends to believe—might see through the conditionality of their relations to their employers by virtue of socialist theory, they nevertheless take the relationships within their own class to be natural and self-evident. But these too are co-constituted by transient social categories, something which only becomes apparent when one actually steps back from them. In order to accomplish this, of course, neither one’s own decision, nor mere reflection, is sufficient. Rather, what is required is a pivotal turn for the worse in one’s social situation, their plummet from all manner of social and human security, in order to make one consciousness a relative outside to fundamental social-economic relationships. Only then can the being [Dasein] actually lose its faith in the naturalness of its conditions and uncover just how many socially conditioned elements were still enclosed within the love, friendship, respect, and solidarity they have enjoyed. In other words, what is required are certain incidents which alter someone’s life to such an extent that the change cannot be made up for. The worker caught stealing from his comrades, the notable official found guilty of embezzlement, the beauty stricken with smallpox and without even the dowry which would render the scarring invisible, the magnate of a trust suddenly bankrupt or in the throes of death may, perhaps, for the first time catch an unclouded glimpse of what they previously considered self-evident. They are about to cross the border.

The Hotel Porter.

The young man and his girlfriend took up residence in a luxury hotel in the big city. They were both excellently dressed, and they had a car of the premier brand at their disposal. Upon checking in, the young man announced that he’d be staying three weeks, and handed the porter a bill [Schein] for his large luggage. The first eight days went swimmingly. The couple often remained in their room, made a few excursions into the surrounding area, and were hardly noticed. But then the young man made a mistake: he gave the porter an excessively large tip for running a minor errand. The porter grew suspicious, looked into the matter, and discovered the facts: the young man was wanted for embezzlement. That very evening, he was arrested. The hotel was frequented by heirs and millionaires; the porter had held his post for many years. It was a perfect match. The young man did not take the porter’s friendly, skilled service—which was, in truth, routine—for granted, as a genuine member of the ruling class would. He had not yet grown accustomed to the abundance of obeisance, courtesy, solicitude which the one who is privileged experiences in all of his dealings in this otherwise terrible society. The young man betrayed himself through impulsive gratitude, and the lack of respect for loose change shown by even the most generous of the hotel’s richer clients. Psychology has yet to shed light on how this comes about in the course of an individual’s life. What is certain, however, is that it shows a wiseness to objective Geist. It seems a secret convention of the rulers to prove the justice of their system, wherein the smallest sum of no consequence to them is often enough to decide the life of the poor, by holding their loose change sacred. This convention had not yet made its way into the young man’s blood. “Something is off here…,” thought the porter. And he was right. The course of the capitalist economy is difficult to predict with respect to share prices. Its effect upon the human soul, however, can be calculated with great precision. A hotel porter seldom errs. With his keen eyes, he exposes less the dishonesty of the guests than the honesty of the hotel.

Note. In Monte Carlo, the rich gambler’s deliberation of whether he should linger a minute longer decides whether he will win or lose several thousand francs. They need not mean anything to him. It’s all the same whether he lays a few more gold-painted chips on the table; what matters is that he has little time before dinner. As he leaves, he may perhaps place one last chip or note on one last card table for one last round. It makes no difference to him if it’s lost—it is, so to speak, surplus. But the lackey who stoops down when the last player to leave drops their last chip is very gratified for one more franc. Would he politely thank him for the franc if the true significance of those spare thousands were demonstrated to by receiving the same in tips just as often as they’re thrown à fond perdu onto the tables? Now that would be unthinkable! In any case, such automatized precaution is far from the mind of the lackey in the gambling hall. He still judges capitalism today by the behavior of the players, and believes, in the end, everyone must gamble away all of their money eventually. But the gentleman, who would rather take the trouble of fumbling around in his pocket for another franc later than leave the lackey the chip as a tip, considers the latter a representative of the underclass and, accordingly, is careful not to corrupt him. Those who aren’t careful are unsteady Cantonists. Their desert is mistrust.

“The work-reddened hand that swings the broom Saturday / On Sunday knows how to give the softest caresses.”

[“Die Hand, die samstags ihren Besen führt, / wird sonntags dich am besten karessieren.”]3

Oh, how far we’ve come from those times! So far, in fact, that according to our psychologically-schooled consciousness, the motive of the lord who marries the chambermaid consists less in nobility than neurotic guilt. Such acts are only pure in bad movies. Today, however, neither marriage nor caressing is left to the maidservant. The bourgeoisie have become fussy, and demand the women they sleep with have become total—in the exact sense of the word: down to skin and hair—luxury commodities. The declassing of the lower social strata also has an impact on erotic valuation. Correspondingly, the economic standing of a man is part of his erotic potency. — One who is nothing in this society, has nothing, becomes nothing, and manifests no real chance of doing so, also has no erotic value. Economic forces can in fact replace sexual ones. The beautiful maiden in the company of an old man is only embarrassed if he has nothing. With the consolidation of the labor aristocracy and the uniformity of society, this boundary may perhaps drop further down, but it will be all the more fateful for those on the wrong side of it.

Value-Blindness.

What I learned about the innate sense of aesthetic value-differences, I learned through champagne. As a child, I was given half a glass, on festive occasions, which was to be drunk in a respectful manner. I didn’t find anything special about it—nor did the maidservant, who was usually asked to join the toast. I did not understand until one day, during a long meal, I quenched my thirst with champagne without paying any particular attention to it; only then was I surprised to discover its special charm. The maidservant, off to the side, certainly remained blind to its value.

Twofold Rebuke.

The child and the grey-haired [Greis]—both clumsy, both rebuked. To their opposite, the woman positions herself within society and represents decency. The secret to this identification lies in the power of that which exists. The woman, at least unconsciously, always signs herself over to the powerful, and the man, albeit silently, recognizes this evaluation as well. While the child is permitted some rebellion against the mother’s admonition, the grey-haired submits to the rebuke of the younger woman in shame. In both cases, clumsiness arises from physical weakness. In the former, however, clumsiness announces a strength still to come; in the latter, only utter powerlessness, death. The child may read some hope off of the woman’s rebuke, but the grey-haired would be right to gather mainly contempt from it.

Tact.

There is an infallible means for recognizing a man’s tact. There are women at every social event who don’t quite measure up to the others in influence, power, security in their manners or beauty. For such inferior feminine participants, the event tends to be a martyrdom, particularly if their man, boyfriend, or girlfriend is preoccupied with the festivities for economic or erotic reasons. They have the feeling of being excluded, and they emit it so strongly that anyone entering or saying goodbye easily forgets to reach for their hand. The tact of the most sought-after and wittiest man-of-the-world proves itself to be a vain illusion if he actually commits this omission; whoever grants a word to such women and draws them into the conversation proves themselves superior to him in his own department. This assessment applies, with corresponding nuances, to sociabilities across the most diverse levels of society, so far as ‘tact’ is understood as something which includes not only what is customary or what is imitated, but also understanding and goodness.

Metaphysics.

What doesn’t one understand by the word ‘metaphysics’ today! It is very difficult to find a formulation pleasing to all the learned gentlemen with all their views on ultimate things. As soon as you’ve tackled any one pompous “metaphysics” with some degree of success, all the others will surely explain that they have always understood metaphysics to be something else entirely.

Yet, it seems to me that metaphysics, in one way or another, signifies cognition of the true essence of things. Judging by the example of all significant and insignificant philosophical and unphilosophical professors, the essence of things is such that one may investigate it, and even live in contemplation of it, without ever falling into indignation with the existing system of society. The wise man who intuits the core of things may indeed draw all manner of philosophical, scientific, and ethical consequences from this vision; he may even sketch out an image of an ideal “community” from it, but his eye for class relations will be little sharpened by this. What’s more, the fact that, under extant class relations, this turn upwards towards the eternal can be taken at all furnishes a certain justification of these relations to the degree the metaphysician assigns absolute value to it. A society in which a man may satisfy his higher calling in such important respects cannot be so bad; at least, its betterment does not appear particularly pressing.

I do not know the extent to which the metaphysicians are right—perhaps there is some particularly poignant metaphysical system or fragment out there somewhere. What I do know, however, is that ordinarily metaphysicians are not much impressed by what torments human beings.

Degrees of Culture (Bildung).

Whenever someone in a bad suit enters a shop, a residential building, a hotel, or even an office, he will experience, as he does in life in general, infinitely less friendliness than someone well-dressed. The world of his betters recognizes him as an outsider on sight from the clothes they’ve dressed him up in. There is something similar in the sphere of “culture” [Kultur]. Whoever has no money to purchase books and no time to study them, whoever has not grown up in the more elevated cultural milieu and does not speak its language, can be found out with a few words. And just as there’s a continuum of transitional stages between the beggar in whose face the little housewife shuts the door and the intimate who is received by the finest society unannounced, there is a continuum of external signs by which the degree with which they belong among the cultured may be recognized. For the worker and the bourgeois autodidact, it goes without saying that every word they utter bears the stamp of their incompetence. But the hierarchy of the cultured is itself finely structured from within. Those who are compelled to borrow their books from libraries only ever receive them long after publication and must promptly return them. They are the inferiors of those who can purchase them, and those who can purchase them are, in turn, the inferiors of those who regularly discuss them. The few who are actually well-oriented are those who associate with the authors themselves, travel a great deal, stopping from time to time in the intellectual centers of the world, and discover which problems and points of view are the most important of the day. How is someone not already an expert in the narrowest domain of specialization supposed to know what particularity of style and conception is what matters in a literary, scientific, or philosophical work! The accidental, obscure grounds on which this depends are, in large part, only to be gleaned from conversations with the augurs themselves. The distinguishing marks which reveal a lack of culture [Bildung] are unmistakable. At higher levels, the use of a single word, precisely because it is in fashion everywhere else, will seem as banal as an expression already out-of-date at lower levels. To the cultivated [Kultivierten], these signs of a lack of culture [Unbildung] make as embarrassing an impression as an ill-fitting suit does to a sensitive lady. When bourgeois intellectuality was still progressive, these secrets of social intercourse may even have been a sign of progress. Today, when the content of cultured conversations, as in capitalist sociability in general, is so far removed from the cares and concerns of humanity, these peculiarities take on an grotesque and embittering character. The degrees of contemporary culture have completely ceased to be stages of enlightenment [Stufen der Erkenntnis], they indicate only vain distinctions in the routine with the semblance [Anschein] of philosophical depth. To be so well-versed in what plays out in the so-called intellectual world, to wear the outfits of contemporary culture, to betray such an affinity with it—today this means a greater, more final distance from the cause of freedom than a well-fitting suit made of the right material. The latter can always be removed at the end of the day; the former only denied.

A Category of the Big Bourgeoisie.

In dealings with the big bourgeoisie [Großbürgern], at least those of a certain category, one should never ask for anything whatever. You must rather always conduct yourself as if you belong among them in every respect. By treating them badly, you will achieve much more than you would by treating them well, for this only reminds them of the manner of underlings and dependents, towards whom they feel contempt, or at least the need for refusal, in their very blood. From early on, they have been habituated to drowning out their bad conscience towards the dominated classes through brutality, and as soon as they adopt such an attitude towards you in the slightest, you are lost. If you would achieve something in their company, you must find it in you to pat them on the back as one of their own might. Once they’ve granted you what you wanted from them, it would be dangerous to thank them—that is, if you value the further development of your relationship with them. Complete mastery of the art of moving freely and naturally through the circles of the big bourgeoisie is one of the few paths still open for the hardworking to advance.

Note. For many of the big agrarians [Großagrariern], especially the German and those still further to the East, the brutality does not start with bad conscience, but rather from the fact they have acutely felt their human inferiority in their dealings with the more civilized. Lurking behind their consciousness is the dawning thought of just how little they know, they can be, and are. This they refute by ruling at home with the whip.

The Perception of a Person.

If an old beggar comes to the door and declares that he discovered radium or the pathogen which causes cholera in his youth, but has since fallen on hard times by circumstances beyond his control, then it is a question of whether we are scientifically literate enough to immediately put his statements to the test. Suppose we believe him, but find in the course of a short conversation that no trace of his former intellect remains. Then it all just seems a tragic matter of fate. If we later consult an encyclopedia and find the beggar only had an idée fixe, the case loses its significance. But dear God, what has changed! There is something there in an encyclopedia, and some experts might be able to connect radium in their memory with certain dates in the lives of the Curies. Otherwise, particularly if the old man only had a small rut—nothing has changed as far as he’s concerned. Perhaps he did not make the discovery in his youth, but had a number of other equally ingenious and learned considerations of merit. He could very well be a failed physics student whose investigations never attained fame for reasons of sheer coincidence. Don’t most human beings have the stuff to make great discoveries in their youth? What remains of that if there are no external conditions which keep them from becoming old beggars? Nothing but a memory of which a beggar might boast and which—if nothing is recorded in the fable convenue of the encyclopedia—cannot even be tested for its truth. Whether the beggar spoke truth or fell victim to delusion need not amount to any difference in the present. Everything before you, in person, now could coincide with either. Conscious memories, indeed the conscious ego of the individual as a whole, is but a thin veil over his stock of current drives and strivings. Whether this happens to coincide with some parts of the larger tapestry woven by recorded history makes little difference for the existence of the living human being either. He may be as poor in spirit and body as the old beggar, regardless of whether he once conquered kingdoms, as he believes, or actually only herded pigs. The vanity of the skeletons in Lucian’s Dialogues of the Dead about their erstwhile beauty and rank in the world is comical because they happen to be in Hades. But why shouldn’t the boundary which separates old age from youth, or even the new day from the one just run its course, be of the same kind as death? Certainly the experience that someone has once achieved something might allow us to conclude he still might be put to some use in the present; but even this is only probability, and the conclusion could be just as deceptive as the inference of a person’s decency today from their decency the day before. As much someone’s drives and talents, the disposition [Gesinnung] of a human being is even more subject to change; so far as none of these remain the same, the thought that the individual has remained the same ‘in itself,’ that is, the idea of the unity of the person as such, is shaky grounds for attributing someone’s past deeds to their present person. Or, to express my meaning positively: the beggar in error may have as much a right to be credited with the discovery as the privy councilor upon whose breast the medals for it shine.

The Cares of the Philosopher.

Care (Sorge): (Faust II, Act 5): “Have you never known care?" German philosopher 1929: “Just a second! Yes. ‘Care’—that’s the name for the unity of the transcendental structure of the innermost neediness of Dasein in man.”

Gratitude.

In the capitalist system, the most effective of good deeds can only be performed by those with great money or power at their disposal. Consciously or unconsciously, they have an interest in the maintenance of this order of property, and they find gratitude a particularly attractive property for those without any to have. It just doesn’t sit right with them when you disappoint the one who has helped you. If one considers that the vast majority of cases in which promotion, aid, patronage are awarded by the rich themselves, or their functionaries entrusted with the maintenance of such a system, it is easy to understand why a forward-looking orientation, the attack on and critique of the ruling form of society appears not only hurtful to the world but also morally repugnant. In order to fully appreciate this, one must always remember that the critical and revolutionary attitude is expressed not only by participation in certain actions, but also in the adoption and profession of certain theories, typically unpopular, in the most diverse areas of life, down to the details of personal interactions, customs, and countless smaller aspects of one’s lifestyle. Everywhere, those who are concerned with the betterment of human social relations diverge from the desired average; everywhere, they offend. All who show them kindness and accommodation are disappointed again and again. Anyone who would offer them help must expect to get into just as much trouble, so long as they don’t break every rule alongside them as well.

The Person as Dowry.

The share of any one human being in the material and intellectual goods of culture is, in the present, by no means determined by their participation in the social life-process. For those who have nothing, the only condition is this: they must work, for otherwise they may not be allowed to live. When the millionaire works, this occurs voluntarily, out of “higher” motivations, for “nobler” and more differentiated reasons, on the basis of character. Whether someone finds themselves in one situation or the other is not determined by any sensible law, but pure fact, as much a fact as who happens to be hit by live rounds fired in an assault and who is allowed to live. There are innumerable degrees of separation between the one who is without a single skill, the “unlearned,” and the Trustherrn. The higher the level of skill, the lesser the compulsion to work as a presupposition for any entitlement, and, moreover, the more pleasant, satisfying, and educationally valuable one’s work has the possibility of being. This composition of society has the consequence that personal relationships differ remarkably in composition as well. A rich man carries himself into a friendship or tryst as a full and free human being. A poor man must over and over win the award of his bare life, the recognition he is an upright member of human society and not a scoundrel, by participation in the social life-process—which, moreover, is often impossible. He is bound; he belongs much less to himself than to (or do) the rich. The value of the gift which someone might make of their own person, their own being, to a loved one, differs accordingly. It differs according to the social position of the giver, but also according to the position of the recipient. For the little man, every human relationship he might have with his equals contains the danger of further deprivation and double the work. If he makes a gift of his love to a woman of his own class, his already modest life is threatened by further restrictions; a relationship with the same woman affords the capitalist the opportunity to exercise magnanimity and open-mindedness. The most he risks is his vanity: associating with people of the underclass, they may end up valuing him for his position instead of his soul. This tends to be quite embarrassing for him. Unrecognized, the class-foundation of society falsifies even love.

Lies and the Human Sciences.

Who would accuse the human sciences [Geisteswissenschaften] of untruth and hypocrisy today? From the infinite realm of truth, they extract only those theorems which are compatible with the prevailing system of exploitation and oppression. Yes indeed, there is still so much to further “insight” which is, at the same time, not inconvenient in the least!

Peculiarities of the Age.

Among the features of the present age which may appear particularly exotic and peculiar to some future epoch is the manner in which the image of our public and private existence is moulded by the organization of one’s love-life. They will find it most unusual that one of the most important details about a human being was their marital status, i.e., the obligation to love another, specific person indefinitely; that the most significant dates in the life of the individual were connected with the sexual sphere; that a certain man was to appear with a certain woman at each social gathering, festivity, and public occasion; that they would even be buried next to one another—just because they slept together. The moulding of the entire image of social intercourse by a specific physiological necessity won’t exactly be considered “indecent,” since this concept will long have belonged only to the past, but may nevertheless be experienced as some compulsive mannerism or other from this or that tribe of primitives; human beings may be tempted to feel as embarrassed about this as they now do about so many other features of their past.

Character.

You have to be lucky when choosing your parents—not just because of the money, but also the character one stands to inherit. Even if character is not so innate as you might think, it is nevertheless acquired in the course of childhood. Just as you stand to possess certain things and connections, you might also stand to inherit a psychological structure which will enable you to have an illustrious career, while others are excluded from any advancement, even happiness, for their entire lives because of work-related inhibitions [Arbeitshemmungen]. These psychic distinctions so decisive for the outcome of one’s life need not necessarily be traced back to distinctions of equal significance in childhood development. Little causes, big effects—and vice versa! Childhoods which seem utterly different might have similar results, and imperceptible differences can produce utterly opposite characters. Insignificant experiences could have decided that A lives out his aggressive drive in brawls, B in the construction of machinery. Until a short while ago, the development of personality seemed to be determined by some serendipitous inner necessity. Belief in the imprinted form which develops in the course of one’s life has been replaced by knowledge [Wissen] of slight coincidences. As this progresses, human beings will be able to put an end to the handiwork of Fortuna, the counterfeiter, and determine the image of humanity for themselves. Through their education in a rational society, children will be able to unlearn the need to be so cautious in the choice of their parents. Until that time, of course, the distribution of characters will remain almost as unjust and non-purposive as that of fortune.

Serious Living.

The more immeasurable the distance between the lives of the lord of capital and their workers, the less the distinctions between them will come to light. While simultaneously elevating the dress and physical appearance of the upper strata of the proletariat, members of the ruling class are expected not to be too conspicuous in showing just how much better off they are, or just how little a raise in the weekly wages of their workers or white-collar employees factors into the total budget of even a lesser magnate. So far as the lord’s enjoyment does not consist in the direct exertion of power, it blossoms in hidden places. Whereas fifty years ago, the house of the entrepreneur was often built right next to the factory, the worker hardly catches a glimpse of the garage with the Rolls Royce that ferries his director back to the suburban villa. The lives of their wives and daughters, their golf courses and tennis courts, skiing vacations and excursions to Egypt, are so well hidden from the eyes of the exploited that the lord can preach the virtue of hard work in person and the newspapers unmolested. The deepening distinction of existence in Trustkapitalismus corresponds to the uniformization of public life. According to the ideology which is valid today, the open enjoyment of a workless life is nearly as frowned upon as the resolute will to radically better the joyless life of the proletariat. When the worried seriousness on the face of a Trustherrn is replaced by a smile, this smile is not the triumphant smile of the former Herrenklasse, but rather an example of that trust in God a man who performs particularly hard work presents to the public. This is the smile which says: we are all born to work alike, not to enjoy, but what right would anyone have to complain. Any member of this Herrenklasse who unthinkingly lets others in on what a marvelous life is possible in the midst of all the misery, or rather at its very foundation, is like the soldier in a platoon who, as they pass behind enemy lines, clears his throat and betrays the whole company. He is a man without discipline.

Horror over Child-Murder.

Whenever one experiences the horror of today’s world over sexually motivated murders [Lustmorde], particularly attacks on children, they might be led to believe that human life and the healthy development of the individual were held sacred in it. But apart from the fact that the great revulsion over these crimes most often has its own particular psychic sources, under today’s social relations children are blown to pieces in the hundreds of thousands, and for the majority of survivors life means living hell—at this, no revulsion stirs in those hearts which are so easily inflamed. In times of peace, the children of the poor are material for future exploitation; in times of war, target practice for explosives and poison gas. The rulers of this world are rather unjust to be so horrified.

Interests of Profit.

The doctrine that the subjects of the present economic order always act according to their interests is certainly false. Not all who undertake new business ventures act according to their interests; it’s just that those who don’t tend to be taken under themselves.4

Make Way For The Capable (Freie Bahn dem Tüchtigen)

The social order of the present really does lift the most capable [Tüchtigsten] to the top. The demand to ‘make way for the capable’ is long out-of-date.5 Where is the genius of industry among the salaried employees of a large factory who would not have immediately left his colleagues behind? The factory owners would have to be so blind not to notice they would be destined for bankruptcy. The law of value asserts itself with respect to “personalities” as well; when it comes to principles of selection for people, capitalism is brilliant. This doesn’t only apply to business. Go through the ranks of directors of clinics and laboratories and consider whether they aren’t excellently suited to their profession—and this is just one of the more poorly developed branches of industry. There is in fact a capitalist justice, which, like any other system of its kind, of course has its holes; in time, however, these too will be repaired. The capable are—accounting for minor exceptions—rewarded. But one may well ask just what this capableness consists of: it is the possession of those abilities which society in its present form requires for its own reproduction. This includes the skillfulness and staunchness [Gesinnungstüchtigkeit] of the manual laborer, the organizational talent of the manager of operations, and the experience of the leader in the party of reaction. Though their function in the life-process is highly derivative, the good novelist and the great composer are, as a rule, recognized and rewarded accordingly as well. As long as one overlooks the fact that the majority of all human beings today are inhibited in the development and implementation of their productive forces, one can surely say that the figure of the unrecognized genius is all in all a figure of times past. Of course there are more talents out there than good positions. But the latter are at least occupied by the “deserving,” and there is always some room at the top. The capable are accounted for as best as possible. From the standpoint of its reproduction, little can be said against the principle for selection among persons in capitalism. In this respect, a relative order prevails, whatever impact the difficulties of the present may have on the younger generation. But this relative order favors the terrible. One cannot deny that this system places the right people in the right positions. The general directors do their job rather well, and perhaps there are some who even owe their posting to their capableness alone; in any case, it would not be so easy to replace them with those who might be more skilled. But this is just who the “capable” are according to today’s capitalism! Those who are most useful in present industry, science, politics, and art are not those who are most advanced, but elements who are to a large extent backwards in the quality of their consciousness and humanity. This difference is only one of the symptoms for just how anachronistic this form of society has become. Justification for the abolition [Abschaffung] of capitalism by appealing to the need for a principle of selection that would be more favorable to productivity is wrong, because this would mean taking the categories of the ruling economic system as the norm. Anyone who does believes a few repairs will do the trick. We must change society not so that the capable come first, that is, such that they would rule us instead, but, on the contrary, because the rule of the “capable” is itself an evil.

Human Relations.

The economic situation of a specific human being determines his friendships as well. The use of one’s wealth and income for oneself and one’s own family means providing the amenities of life for one’s own and not for others. Genuine, direct relationships cannot be established where the most fundamental of interests of one party are so opposed to those of the other, and such is the case wherever disparity of living standards denies any commonality of wealth or income between them. In bourgeois society, the family thus delineates the circle of direct relationships. Only within the healthy family do the joys and sorrows of one really impact the others. Without identical material interests between individuals, they must at the very least repress jealousy, envy, and Schadenfreude. Therefore, social development destroys the healthy family within broad social strata, above all among the petty-bourgeoisie and the white-collar workers, the sole place in society where they might have direct relationships with other human beings. On the other hand, within certain groups of the proletariat, social development forms new, conscious, communities based on the recognition of common interests, in the place of the naturally occurring, largely unconscious groups, the latest product of whose decomposition is the now-perishing nuclear family. These new communities are not glorified as god-given institutions as was once the case with those naturally occurring associations, from the horde to the nuclear family. The greatest and clearest unity of this type is formed out of the solidarity of the class strata interested in the construction of a new society. The emergence of this proletarian solidarity depends upon the same process which destroys the family. In the past, it was blood, love, friendship, and enthusiasm which seemed to lead to common interest; today, it is common revolutionary interest which leads to love, friendship, and enthusiasm. What stands in the way of the solidarity of all those who would displace present injustice with new justice is not an opposing solidarity to theirs at all, but the common power held and kept by those who rule over them. Not even the relationships between these rulers themselves are direct. The holders of the large capitals may indeed maintain their good manners in the salon and even call themselves “friends,” but their capitals are organized colossi become autonomous from the persons and relationships of their owners. The handshake which passes between two magnates means so little that one cannot tell whether in that very instant blood is spilling elsewhere over the opposing interests of their capitals. Their relationships as persons have evidently become so immaterial to the real consonances or contradictions of their capitals that the warning “I’ll ruin you if I have to” no longer need follow their warmest greetings to one another—that much is self-evident. This fact forms the general presupposition on the grounds of which rather friendly, and other altogether unreserved relationships are possible. The ruling order of today, which is inextricably linked to the wealth and income of each member of the big bourgeoisie [Großbourgeoisie], rests upon such great need and misery that the idea of hesitating before ruining a dozen of their friends to save a greater part of their wealth would never occur to them. Their private community is subject to this slight restriction; their social community consists essentially in the suppression of the proletariat.

On the Distinctions of Age.

When an unemployed worker or salary man is over forty, it becomes difficult for him to find any employment nowadays; if he is already employed, he has to fear being let go. The younger competition works more efficiently for less. The elder becomes a valueless, clumsy elder, a burden to all. When a distinguished businessman, a Councilor of Commerce [Kommerzienrat], turns sixty or seventy, his company throws a party in his honor. The speeches delivered over dinner testify to how much the labor-power and experience of the esteemed senior has meant and still means to the firm and, what’s more, to the entire branch of industry. Even the qualities of age vary according to class position.

‘Suffering Teaches Wisdom’ (Durch Schaden wird man klug).

… That may be, but the surest path to wisdom is that of success, and, if it must pass through suffering at all, then let it be the suffering of others! The presupposition of so-called capable men in the most diverse fields is, in part, that they have rapidly come into a social situation which gives them the right overview of the apparatus of their chosen profession and the self-confidence to take advantage of it. Failures, suffering, on the other hand, only make one fearful, and as is well-known there is no greater check [Hemmnis] to learning than fear.6

Double Standard.

Motto for the friends of the existing order: “Woe to he who lies.” He may live by, with, or from his conviction. Motto for those who are horrified by it: “Woe to he who lies not.” He may founder by, with, or from his conviction.7

On the Relativity of Character.

Whether Genghis Khan composed sonnets, I cannot be certain; but he may well have been a charming entertainer. Whatever the case might be, his confidants surely had a different experience of him than defeated princes and prisoners of war. Conversely, the poets and scholars who occupy an honorable place in the history of cultural progress participated in the most up-to-date methods of domination, under the patronage of their own respective Genghis Khans, and, accordingly, were counted among the dominated of their epoch as one of the devil’s company. The moral qualities of human beings are relative; they depend on the situation, above all the class situation, of the one who has first-hand experience of them. It is not just that they appear different according to the relationship one has with them; they are different. The relativity of which we speak is not the same as, for instance, the phenomenon in which an image appears to be larger or smaller depending on the position of the viewer, though in actuality it remains the same size. The seemingly fixed dimensions of the human being are not quite as far removed from us as those of the things in our immediate environment, though even physics has come to hold that the dimensions of things do, in fact, depend to some extent on the movement of the observer. The patron who is refined and generous to the artist may in reality be an exploiter to his workers, the enchanting lady a real tormenter to her chambermaid, the devoted civil servant often a true tyrant to his family—the various human qualities are not merely ‘aspects’ in which they appear to various persons, but realities which exist in the relationships themselves. The experience that this or that person is better or worse than I previously considered them to be typically depends on some change in my own social situation; such a change disposes the other to behave with greater friendliness or hostility towards me. You need only to win the big lotto ticket to discover the majority of human beings have suddenly improved. A few of your former friends may be petty and “immediately offended” afterwards. Have you ever had occasion to notice a change in the tone of their voice when an acquaintance discovers you are not, as they had previously imagined you to be, well-off, but poor, and realizes you might end up wanting something from them? Have you ever observed the distinction between the manner in which everyone does favors for their poorer and richer acquaintances? When they come face to face with one who has acquired power, the majority of human beings transform into such helpful, friendly creatures. When they come face to face with the absolute powerlessness, as with that of animals, they transform into cattle-dealers and butchers.

Waiting.

Having to wait stands in exact proportion to one’s position in the social hierarchy. The higher one’s standing, the shorter they wait. The poor wait in front of the factory office, the government office, the doctor’s office, on the train platform. They even take the slower train. Waiting is aggravated by having to stand; the last-class train car is typically overfull, and many must stand to ride in it. The unemployed wait all day. That every minute more a general director must wait at the banker’s is an indication of his poor credit rating is widely discussed; such knowledge is a concern of the philosophy of the capitalist businessman. That waiting which has been a constant feature of the life of the dominated class through all epochs is less often discussed in bourgeois society; such knowledge does is of no concern to the business of capitalist philosophy. The majority of human beings wait for a letter every morning. That it does not arrive, or holds a rejection notice, applies as a rule for those who are sad anyway. The richer the addressee, on the other hand, the more pleasant surprises the morning post brings—unless, that is, the economic crisis has shaken this up as well and draws them into the process of social restructuring too.

To Forget.

When one has sunk their deepest, exposed to an eternity of torment inflicted by other human beings, he nurtures the thought that another will come, one in the light, and dispense truth and justice, as if this wishful image would redeem. It need not even happen in his lifetime, nor in the lifetimes of those torturing him to death, but only one day, at some point, everything should be set aright. The lies, the false image of him spread through the world without him being able to defend himself against it, should one day wither before the truth, and his actual life, his thoughts and goals, as much as the suffering and injustice inflicted upon him, should be revealed. It is bitter to die misunderstood, and in the dark. Illuminating such darkness is the honor of historical research. Seldom have historians forgotten this as decisively as in the effort of the present to dispense historical “understanding” to the former ruling classes and their henchmen. The dreams of heretics and witches that a better, more human century might look back upon them have, in fact, been so well fulfilled that our scholars and poets today dream of turning back to that darkness—not out of youthful longing to liberate the victims, but in order to hold up those blessed times as a pattern for the present.

Excerpts from: Gunzelin Schmid Noerr, “Nachwort des Herausgebers. Die philosophischen Frühschriften. Grundzüge der Entwicklung des Horkheimerschen Denkens von der Dissertation bis zur ‘Dämmerung,’” in: Max Horkheimer, Gesammelte Schriften. Band 2: Philosophische Frühschriften 1922-1932. Edited by Gunzelin Schmid Noerr (Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, 1987), 455-469. Author’s translation.

For some reason, this sentence is missing from the Shaw translation of “Monadology,” but not from the 1974 republication nor the later MHGS edition of Dämmerung.

Faust: Part One. In: Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Faust: A Tragedy. Parts One & Two. (Fully Revised), Translated by Martin Greenberg (Yale University Press, 2014), 32. (lines 868-869)

[Nicht alle Unternehmer handeln nach ihren Interessen, es pflegen nur die, welche es nicht tun, zugrunde zu gehen.]

Translation attempting to capture Horkheimer’s wordplay with “Unternehmer,” literally ‘undertaker’ (in the original sense of entrepreneur), and “zugrunde zu gehen,” which is colloquially translated as ‘perishing’ but literally means foundering—going or returning to the ground. Goethe makes use of the term “zugrundegehen” in Faust (“denn alles was entsteht / ist wert, dass es zugrunde geht” [“For whate’er to light is brought / Deserves again to be reduced to naught…”]), and Hegel often plays on the words “zugrunde gehen” (foundering, perishing) and “Grund” (foundation, ground).

For an examination of Hegel’s appropriation of Goethe’s “zugrundegehen,” see: Jeffrey Champlin. "Hegel’s Faust" In Goethe Yearbook 18 edited by Daniel Purdy. (Boydell and Brewer, 2011), 115-126.

Horkheimer’s aphorism can be read as a repudiation of ‘the conservative revolutionary’ Paul Ernst’s “Freie Bahn jedem Tüchtigen” [1919] [In: Tagebuch Eines Dichters. Edited by Karl August Kutzbach (München : Albert Langen/Georg Müller, 1934) [link]], written in the same year as Ernst’s repudiation of Marxism in Der Zusammenbruch des Marxismus [(G. Müller, 1919) [link]].

“check”: Hemmnis—both something that inhibits [hemmend] and aggravates [erschwerend]; as both ‘resistance’ and ‘stimulus’ for overcoming in Nietzsche’s Will to Power, see: Andrea Rehberg, “The Overcoming of Physiology.” The Journal of Nietzsche Studies, Issue 23, (Spring 2002), 46-47.

Much like the aphorism “Interests of profit” [Profitinteressen] (see note 25 above), “Double Standard” [Doppelte Moral] is a play on the phrase ‘zugrunde gehen’:

Leitspruch für den Freund der bestehenden Ordnung: »Weh dem, der lügt.« Er kann nach, mit, von seiner Gesinnung leben. Leitspruch für den, der über die bestehende Ordnung erschrickt: »Weh dem, der nicht lügt.« Er kann nach, mit, an seiner Gesinnung zugrunde gehen.

Or: the horrified whose motto is “woe to he who lies not” [“Weh dem, der nicht lügt”] might very well lie still—having foundered or perished or ‘run aground’ [zugrunde gehen] because of their conviction [Gesinnung], that is their basic attitude [Grundeinstellung], towards the existing order. The aphorism turns on this wordplay: those whose motto is “woe to he who lies” lie not (for they do not perish by their conviction); those whose motto is is “woe to he who lies not” lie still (for they do perish by their conviction). The existing order [der bestehenden Ordnung] makes each of these mottos into a self-fulfilling prophecy.