Dämmerung I: Horkheimer's Weimar Journals (ca. 1920-1928)

I. Philosophical Journals (ca. 1920-1923); II. Philosophical Journals (1925-1928)

Prologue to a series of translations of texts for, from, or contemporaneous with Horkheimer’s Dämmerung. Notizen in Deutschland (1934).

Dämmerung II: Notes For Dämmerung (1926-1931)

Dämmerung III: Aphorisms from Dämmerung (1934) (forthcoming)

Dämmerung Appendix I: Sketches for a Negative Metaphysics. Herbert Marcuse (ca. 1933)

Dämmerung I. Table of Contents.

Translator’s Note.

Translator’s Remark.

I. Philosophical Journals (ca. 1920-1923)

A. Twofold Equality (ca. 1920?)

B. Two Entries on the Wager (July 5th-6th, 1923)

II. Philosophical Journals (1925-1928)

Entry No. 1 (8/21/1925)

Entry No. 2 (9/6/1925)

Entry No. 3 (9/12/1925)

Entry No. 4 (9/16/1925)

Entry No. 5 (9/19/1925)

Entry No. 6 (9/25/1925t)

Entry No. 7 (9/27/1925)

Entry No. 8 (10/10/1925)

Entry No. 9 (10/20/1925)

Entry No. 11 (11/13/1925)

Entry No. 12 (3/13/1926)

Entry No. 13 (3/17/1926)

Entry No. 14 (5/20/1926)

Entry No. 15 (6/3/1926)

Entry No. 16 (7/1/1926)

Entry No. 17 (7/9/1926)

Entry No. 18 (7/10/1926)

Entry No. 19 (7/21/1926)

Entry No. 20 (7/26/1926)

Entry No. 21 (7/30/1926)

Entry No. 22 (11/18/1926)

Entry No. 23 (11/26/1926)

Entry No. 24 (12/10/1926)

Entry No. 25 (12/18/1926)

Entry No. 26 (2/2/1927)

Entry No. 27 (7/26/1928)

Entry No. 28 (11/22/1928)

“The spoils which fall to the fascist belong to him by right: he is the legitimate son and heir of liberalism. The wealthiest estates have nothing to reproach him with. Even the most extreme horrors of today have their origins not in 1933, but in 1919, in the shooting of workers and intellectuals by the feudal accomplices of the first republic. The socialist governments were essentially powerless; instead of advancing down to the very basis of these events, they preferred to remain on the loose topsoil of the facts. In secret, they held the theory to be a quirk. The government made freedom a matter of political philosophy instead of political practice. Even those who may privately have every reason to do so should not wish humanity to repeat this. It would run the very same course as the original.”

—Horkheimer, ”The Philosophy of Absolute Concentration” (1938).

Translator’s Note.

The following collection consists of original translations of two short series of journal entries written by Horkheimer in the course of the 1920s, originally published in Horkheimer’s Gesammelte Schriften, Band 11 (1987):

The “[Verstreute Notizen] [1920-1923]”:

The first, “[Zweierlei Gleichheit],” tentatively dated by the editors of the MHGS: [ca. 1920].

The second, “[Zwei Tagebuchblätter],” dated individually by composition: [5. Juli 1923]; [6. Juli 1923].1

The “[Philosophisches Tagebuch],” 28 entries dated individually by composition—the first, 8/21/1925; the last, 11/22/1928.2

Translator’s Remark

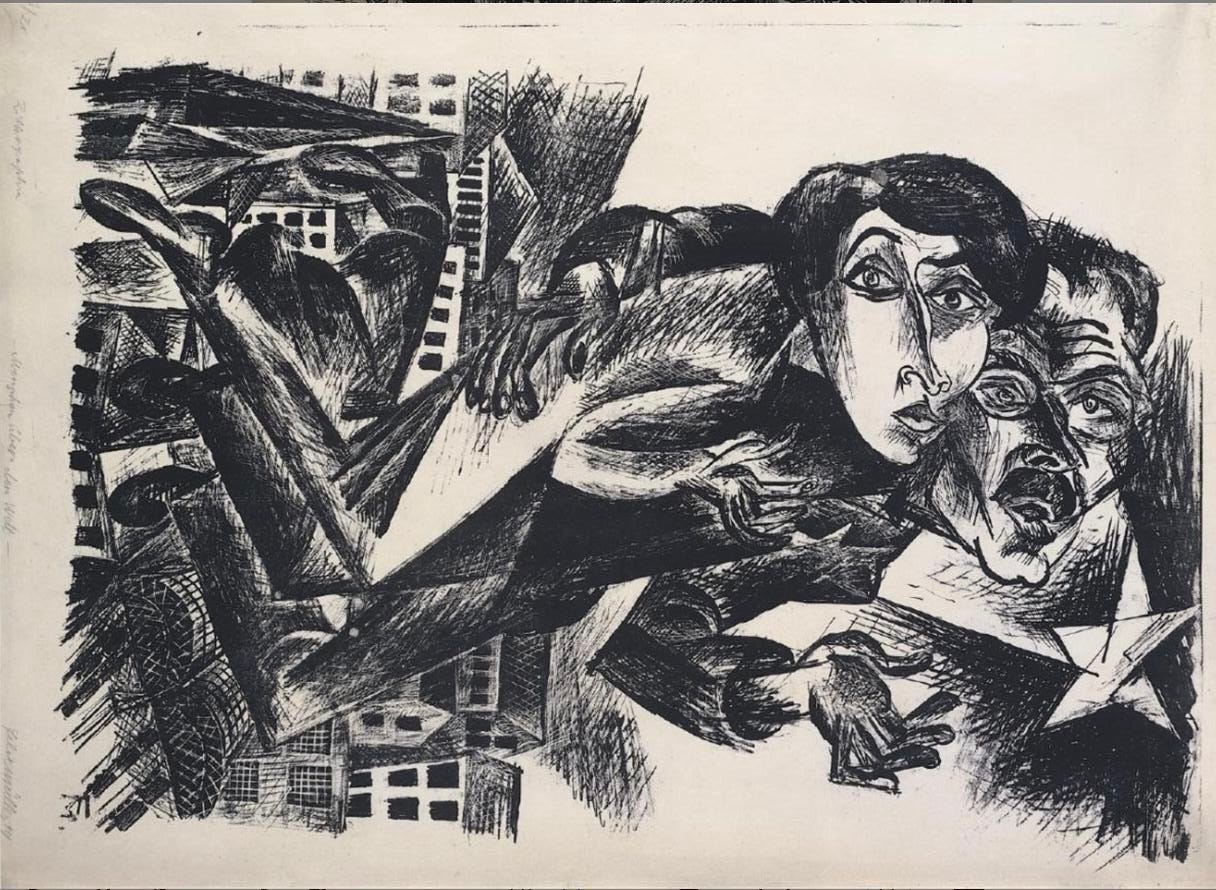

Horkheimer’s early philosophical journals serve as a kind of prologue to his book of aphorisms: Dämmerung: Notizen im Deutschland, written 1926-1931, published 1934 under the pseudonym ‘Heinrich Regius.’ In the following journal entries—the first three entries from approximately 1920 through 1923; then the twenty-eight entries of the ‘philosophical journals’ dated 1925 through 1928—we see Horkheimer somewhere between Kierkegaard and Marx, as much a critic of vicious immanence as false transcendence. On the one hand, Horkheimer adopts the “paradoxical bearing” (see: Entry No. 16 [7/1/1926]) of Kierkegaard, as we find in Johannes de Silentio’s Fear and Trembling [1843], revealing the absurdity of the universal ethical norm of the existing world order—of ethical life, the family, the state—by forcing it to betray its abstractness and particularity in dramatizing the violence it brings down upon the existing individuality of those who are subject to and of it. On the other, Horkheimer echoes the class-critical rancor of the young Marx’s reading of Eugène Sue’s Les Mystères de Paris [1842/43] in The Holy Family [1844], demonstrating how the humanistic philanthropy of the ruling class and its intellectuals towards the ideal ‘man as such’ is in fact misanthropy, an ideological substitute for the “real humanism” of solidarity with the corporeal miseries and joys of individual human beings as they are.3 In Horkheimer’s non-academic writings of the 1920s, figures like Kierkegaard and Marx appear and reappear in the company of social critics outside of the ‘critical philosophy,’ Kantian and Neo-Kantian, which dominated Horkheimer’s academic environment. For Horkheimer, the anti-rationalist partisan of the one Logos (see: Entry No. 7 [9/27/1925]), the critique of the abstract universal in Kierkegaard and Marx is a model for a kind of concept-formation that begins precisely where others have given or closed their concepts up—wherever the concept conflicts with its motive and object.

While The Holy Family itself wouldn’t be published until 1932,4 Horkheimer’s rapid incorporation of Marx’s ‘early’ polemics in his essays of the 1930s—for instance, in his use of Marx’s review of Peuchet’s On Suicide [1845/46] to define a central dynamic of class-mediated reconstitution of patriarchy in “Authority and The Family” [1935/36]5—is undoubtedly due to the fact that Horkheimer had long since developed not only a socialist critique of ‘the philanthropic bourgeois,’ but an immanent one. Marx’s methodological note at the beginning of “Peuchet: On Suicide” could have been penned by the Horkheimer of ~1920 himself:

It is by no means only to the French “socialist” writers proper that one must look for the critical presentation of social conditions; but to writers in every sphere of literature, and in particular of novels and memoirs. […] It may […] show what grounds there are for the idea of the philanthropic bourgeois that it is only a question of providing a little bread and a little education for the proletarians, and that only the worker is stunted by the present state of society, but otherwise the existing world is the best of all possible worlds. With Jacques Peuchet, as with many of the older, now almost extinct, French professional men, who have lived through the numerous upheavals since 1789, the numerous disappointments, enthusiasms, constitutions, rulers, defeats and victories, criticism of the existing property, family, and other private relations, in a word of private life, appears as the necessary outcome of their political experiences.6

For Horkheimer as much as for Marx, immanent critique cannot adhere exclusively to either the perspective of the author’s intention or the perspective of the sociologist who later passes judgment on the social significance of the work:

From the vantage point of their creator, the aesthetic creations, in which the sociologist later sees the reflections of a particular society and its epoch, appear as innovative, thoroughly “originary” products. There exists no prestabilized harmony between the potential of creative works to express something of society and the individual intentions that give rise to such works. Works of art attain their transparency only in the course of history.7

Immanent critique is therefore neither an ‘internalist’ nor an ‘externalist’ method, but poses the problem of the changing relationship of the artwork to society which encompasses—both grounds and relativizes—the ‘first-person’ perspective of the creator and the ‘third-person’ perspective of the sociologist.

§2. Dialectical Problemata—From Equality to Solidarity.

In his editorial remark to the ‘stray notes’ (here: ‘Philosophical Journals (ca. 1920-1923)’) Noerr writes that the first, (A.) “Twofold Equality” [Zweierlei Gleichheit] [ca. 1920?], is motivated by the same impulse as Horkheimer’s earlier—primarily literary, later collected in Novellen und Tagebuchblätter [1918]—sketches, namely: “the experience of the World War, the revolution, and the uprisings of the immediate post-war period”; the second (B.) “Two Entries on the Wager” (July 1923), Noerr continues, “serve Horkheimer’s [desire for] self-understanding [Selbstverständigung] with regard to his own motive, which is to philosophize.”8 While they lack any strict form, they follow a pattern which, to take a cue from Horkheimer’s later journals, resembles the dialectical problemata as constructed by Kierkegaard’s Johannes de Silentio, author of Fear and Trembling [F&T] (1843). In a first step, theoretical reflection begins by assuming the perspective of a universal—in (A.) equality; in (B.) philosophy itself—and by deriving from it at least one rule which must be followed for its concept to be fulfilled. In a second step, a conflict is introduced between fidelity to the universal and obedience to the rule derived from it, in what Kierkegaard’s de Silentio calls a “dialectical consequence” or “paradox,” which “is capable of transforming a murder into a holy act well-pleasing to God” (F&T),9 of transforming a poet who gives voice to the hungry into a propagandist for the state feeding them to war (A. ‘Equality’), or of transforming an uncompromising philosophical insight into an insight into the compromise of philosophy itself (B. ‘Wager’).

Noerr makes a connection between (A.), ‘Twofold Equality,’ to Horkheimer’s later entry “Entry No. 4 (9/16/1925)” from the Philosophical Journals of 1925-28, where Horkheimer’s reflections on the problem of solidarity result in a unique twist on the ‘dirty hands’ thesis. Horkheimer refuses the temptation to identify with the proletariat to which he considers himself, and other ‘sons of rich parents,’ particularly susceptible. This identification has too much in common with that of the entrepreneur who hides their enjoyment in the midst of the misery that enables it “from the eyes of the exploited [so] that [they] can preach the virtue of hard work in person and the newspapers unmolested.”10 The rich kid ‘slumming it’ in revolutionary garb gets their edge by seeking out the company of those whom, to use Horkheimer’s scatological idiom of the time, their own class has smeared in the shit [Kotige: fecal matter, excrement] of the vast digestive apparatus [Verdauungsmaschine] of capitalist class domination. By ‘dirtying their hands’ in this way, they clean their conscience. To “love the poor as such for this reason” (viz., that they are poor) “would mean preferring the proximity of an animal deliberately and maliciously smeared with filth by others to the proximity of an animal those others have kept clean.”11 Whichever the case may be, the poor loved as such, or loved for their poverty, are loved on the condition of their enduring animality.

In “Twofold Equality,” Horkheimer compares the way the “Volksfreunde” type of intellectual—the Narodnik, following Lenin (as Horkheimer does)—relates to the poor, whose ‘authenticity’ they romanticize and whose ‘backwardness’ they embrace, with the way one would “feed their chained hound with sugar.” The volksfreundlich intellectual has their precursor in Eugène Sue’s Rodolphe, Grand Duke of Gerolstein in Les Mystères de Paris (1842/43)—having disguised himself in the costume of a Parisian worker, Rodolphe takes an extended vacation from his duchy for excursions into urban hovels of ill-repute to save the wayward lumpens and proles not from their poverty in fact but their poverty in spirit. Rodolphe teaches the butcher’s-son-turned-murderer, Le Chourineur, a thing or two about honour in a tavern-brawl-turned-sermon, bringing the brute to heel, and even sicking him on other reprobates.12 There is no more perfect misanthropist than the philanthropic bourgeois.13

In “Twofold Equality,” Horkheimer’s example of the “reversal of the bourgeois-gentilhomme” is Gerhart Hauptmann (1862-1946), erstwhile ‘leftist’ author and social-democratic critic of the empire who, on both sides of WWI, in 1914 and again in 1919, proved himself volksfreundlich enough to set aside the divisive Klassenbewußtsein he appealed to as popular writer for the unified Nationalbewußtsein he rallied to as state poet in his people’s great hour of need.14 In both “Twofold Equality” and “Entry No. 4 (9/16/1925),” we see first steps in a rearticulation of solidarity through the mediation of its impossibility, its impossibility under the very same conditions of class domination which make it necessary. It is in this sense that Horkheimer says there is a kind of internal equality of the proletarian and intellectual in that each “may fight their own struggle”—namely, a struggle against the society defined by class struggle itself and the calcifications of ‘intellectual’ and ‘proletarian’ we’ve secreted to protect ourselves within it.

§3. Selbstbesinnung—The Problem of Professional Philosophy.

The entries from Horkheimer’s ‘Philosophical Journals’ are individually dated by composition, from 1925 through 1928. This partly overlaps with the period of time in which the aphorisms for Dämmerung were written (1926-1931), and some entries read like they were torn right from its pages. (For instance: Entry No. 28 '[11/11/1928], in which Horkheimer expresses concern over the depoliticization of revolutionary workers as a result of their integration into the labor aristocracy, management, and civil service.)

In his “Prefatory Remark” to the entries in MHGS, Bd. 11 (1987), Gunzelin Schmid Noerr writes:

These journalistic entries were in part produced in parallel to those for Dämmerung, but, unlike them, not meant for publication from the outset, but rather only for self-understanding [Selbstverständigung]. With regard to form and content, the common points of reference with Dämmerung are obvious; Ideologiekritik of bourgeois society is still the common theme. In contrast to the notes for Dämmerung, however, the center of gravity here is above all the problems of contemporary philosophy on the one hand, and on the question of Selbstbesinnung [self-reflection] on the other. In the winter semester of 1925/26, Horkheimer began teaching as a Privatdozent and found himself confronted with neo-Kantianism, phenomenology, Lebensphilosophie, and other academic currents, against which he attempted to stake out a position of his own. Above all, it is this end the diaristic entries serve. Motifs which will, at a later time, be so important for critical theory—such as the relationship to the enlightenment, as well as the critique of an objectivistic, reductive and reduced Marxism, “which foregoes the reality of the individual under the concept of class”—are already present here in nuce. The notes can be read as a continuation of the earlier, literary experiments on a new, theoretical level. This is demonstrated by things like the sudden, private confrontation with the normative demands of his parents, but above all the reflection [Besinnung] of a philosophical commitment to truthfulness beyond academic self-sufficiency, or the ongoing consideration of the decision for socialism as a moral problem.15

There seems to be a deeper coherence to these entries, however. As Horkheimer continues to add entries to these journals, an internal system of references begins to develop. The most explicit internal reference is made explicit by Horkheimer himself, as he concludes ‘Entry No. 15 (7/1/1926),’ on the topic of the Immanenzphilosophie (philosophy of consciousness), by referring back to ‘Entry No. 4 (9/11/1925).’ The latter is one of the most dizzying in the whole series: beginning with two paragraphs on the Immanenz-philosophical error of solipsism in theory, Horkheimer seems to suddenly pivot in the last sentence of the second paragraph to the problem of solidarity, the focus of the third. The cohesion of the entry lies in this seemingly abrupt shift of registers: the theoretical solipsism of Immanenzphilosophie is rearticulated in light of the social solipsism of the philosopher. Through this rearticulation, the illusion of solipsism is shown to have a social reality of its own, and theoretical criticism ends by reorientation to problems of historical praxis.

In other words, for the error of philosophical solipsism to be solved, the social solipsism of the philosopher, their position in bourgeois culture and the capitalist system of class domination, must be challenged in practice. But in one final turn of the dialectical screw, Horkheimer critiques the appeal to historical praxis itself—since, as in the case of the philanthropic bourgeois who loves the poor ‘as such,’ the uncritical appeal to historical praxis as a magic bullet reproduces the social solipsism of the philosopher. There is nothing sadder than the philosopher whose ‘praxis’ consists in parroting revolutionary slogans about the importance of praxis to other social theorists. It is not sufficient to oppose philosophical solipsism to ‘love of the proletariat, the poor, the masses.’ Only self-perficient solipsism can coincide with true solidarity, since only this can do justice to the reality of the solipsistic illusion while simultaneously refusing to accept it as an ultimate truth.

By connecting ‘Entry No. 15 (7/1/1926),’ which seems politically innocuous by comparison, to ‘Entry No. 4 (9/11/1925),’ Horkheimer makes the connection between the more political entries and the more academic entries explicit. There is an essential connection between the theoretical topos—problems in contemporary philosophy and the question of Selbstbesinnung—and biographical occasion—Horkheimer’s first semester of teaching as a Privatdozent—that becomes increasingly apparent in the journal entries: the problem of the social theorist as a professional academic. The later ‘Philosophical Journals (1925-1928)’ provide a unique relay between Horkheimer’s ‘non-academic’ and ‘academic’ writings of the late 1920s and early 1930s—not because they reconcile the tension between these two modes of authorship, but because they dramatize it. In Horkheimer’s search for self-understanding, we see the germs of the self-reflexive approach that characterizes critical theory: “[W]e expect the philosopher of history and the sociologist to be able to show how their individual theories and concept formations and, in general, every step they take are grounded in the problematic of their own time.”16 The critical theory of society requires a social critique of its theorists.

Lastly, there is a deeper unity between what Noerr calls the ‘motifs’ of later critical theory—a relationship to the enlightenment, a critique of reductive/reduced Marxism—and what Noerr over-qualifies as ‘the ongoing consideration of the decision for socialism as a moral problem.’ The influence of the enlightenment—particularly the French enlightenment tradition—is evident from the beginning, since the notebook opens with epigraphs from comte de Mirabeau and Voltaire on the virtues of enlightening thought. In several entries—particularly ‘Entry No. 3 (9/12/1925)’ and ‘Entry No. 13 (3/17/1926)’—the intimate connection between avant-garde bourgeois philosophy and Marxist social critique is implied, anticipating the self-stated project of the Rettung in Adorno and Horkheimer’s discussions of the planned but unwritten sequel to the Dialectic of Enlightenment in 1946: “holding fast to the radical impulses of Marxism and, in fact, of the entire Enlightenment—for the rescue of the Enlightenment is our concern.” In the lecture courses on the history of modern philosophy he delivers through the late 1920s, Horkheimer is even more explicit that the true heir of the radical impulses of the French enlightenment tradition is the socialist critique of society.17 In ‘Entry No. 3 (9/12/1925),’ we see Horkheimer celebrate Voltaire’s outspoken refusal to entertain the rationality of torture in the justice system (in contrast with Diderot) and his advocacy on behalf those martyred by it, quoting from Voltaire’s defense of the Chevalier de La Barre, a young man who was tortured to death in 1776 for blasphemy in his conduct at religious services and his admiration of irreligious texts, including Voltaire’s own Dictionnaire philosophique [1764]. Before the sanguis innocens of the martyr La Barre, Voltaire formulates his mission as a critic as follows: “Je veux crier la vérité à plein gosier; je veux faire retentir le nom du chevalier de La Barre à Paris et à Moscou; je veux ramener les hommes à l’amour de l’humanité par l’horreur de la barbarie.“18 So for Horkheimer before the bodies of Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht, Kurt Eisner, Gustav Landauer, and Eugen Leviné in the summer of 1919.

I. Philosophical Journals (ca. 1920-1923)

A. Twofold Equality (ca. 1920?)

Let’s finally denounce the barbaric, totally ridiculous (reversal [Umkehrung] of the bourgeois-gentilhomme) social inebriation of the bourgeoisie.19 Man has—God damn it!—one, single task: to live according to his personality, disposition, or whatever you wish to call it; that is, whatever is synonymous with being efficacious, creative, honest. The Volk, the raw masses, are the natural enemy of the refined, intellectual human being. Each may fight their own struggle—in this sense, there is an equality—internally, certainly not externally—of the proletarian and the intellectual, namely that equality of all for whom struggle is necessary. The other equality, of the pack of “Volksfreunde”(*), swindlers of the general public and con artists, either feed their chained hound with sugar, or—reversal of the bourgeois-gentilhomme: Gerhart Hauptmann.

[MHGS Ed. Note] (*) Name for the Russian Narodnik movement, which, especially in the 1870s, preached for intellectuals to “Ins-Volk-Gehen.” These “Volksfreunde” or “Volkstümler” regarded the peasant village community as the germ-cell of socialism [die Keimzelle des Sozialismus]. Lenin criticized them in his text, “What the ‘Friends of the People’ Are and How they Fight the Social-Democrats” [“Was sind die Volksfreunde und wie kämpfen sie gegen die Sozialdemokratie?”] (1894).

B. Two Entries on the Wager (July 1923)

Entry No. 1 (7/5/1923)

“This drive to seek out knowledge of the stuff of life, its trials and tribulations, the goal of which you always hope to win as ‘truth’ in a future period of your life, and cannot even really envisage in the present—what does this truly afford you in your life, without beating around the bush: how are these strivings rooted in the concrete core of your person, from and for which you live out your life; these things which, as you move in the rhythm of the real cares of the day, bear such distinguished names?”

This is a thought which has often disturbed my comfortable satisfaction with theoretical lessons. The answer is always rather abstract; roughly, in the style of: first weigh, then wager [erst wäge, dann wage]—in connection to humanity in general and to myself, i.e., our community in particular. When I subject this reply to more thorough examination, I note a suspect relationship between it and the notion of a division of labor, the principle of which could spoil my taste for theory as a whole. The essence of the relations: Truth—Life, Consciousness—Being, Philosophy—Praxis, this is obscure to me too, yet I’ve already spent countless hours doing so, what I call philosophizing. Was I supposed to have thought about it beforehand? How—to justify the way I’ve used all these hours, was I supposed to have reflected on it? And I wagered anyway? How to bear this?

Entry No. 2 (7/6/1923)

The wager [Wagnis] doesn’t spring from consciousless drive alone, lurking behind the back of one’s thought. Somehow, something known, an express “ground,” plays some role in the motivating situation, if only a supporting one. The conceptual—such that we can get a grasp on it later—reversal [Verkehrung] of what enters the situation in the form of judgments into its opposite would change it—even if only superficially, as if from the outside. Apart from the fact that essential situations are continuously influenced, even interwoven, to a high degree by concepts, prior experiences, habitual interpretations, only the so-called “ground,” the conviction that there’s a relationship between the present situation and the one to be realized through the wager, really matters. It is, after all, a co-determining moment. Modifications of the conviction may reconfigure the situation and reorient the action within it. This—the conviction—is subject to logical laws; we believe it, and, alongside natural attempts to “look ahead,” to broaden the situation overall by means of the methodical conduct of experience, to enrich it, to extend it spatio-temporally, not only does the concern arise, and increase to the degree this endeavor succeeds, to draw everything into it, to put these riches to use—but also the fear of the autonomous right [Eigengesetzlichkeit] of its logic, above all the horror of falling prey to the law of contradiction, the suspicion that it’s not just the knowledge of purely experiential elements which might have an affect the effect; one no longer just seeks one correctness after another, but brings “philosophy” into it. What does this mean for the situation itself—and for the wager?

II. Journal Entries before the Dämmerung (1925-1928)

“L'ignorance a fait et fera à jamais les tyrans et les esclaves.”20

“... toutes les vérités sont nécessaires et utiles aux hommes; toute erreur leur est funeste.”21

— comte de Mirabeau.

“En un mot, moins de superstitions, moins de fanatisme; et moins de fanatisme, moins de malheurs.”22

— Voltaire.

Entry No. 1 (8/21/1925)

The history of philosophy from Kant through Hegel is to be presented in such a way that what appears as a single thread of thought, tied to a sole, concrete hook and spun out by means of sheer stubbornness (Fichte), does not hold out, regardless of how many more connecting segments one smuggles in (Hegel). Actual cognition [Erkenntnis] is not yet such a rock of truth that one could lower oneself from it with the class-rope of non-contradiction into the ocean of (“systematically derived”) assertions.

Entry No. 2 (9/6/1925)

It is easier converting to a completely modest, ascetic life from all of the enjoyments of extravagance than it is from a conventional, bourgeois household [Ménage]. At the very least, if youth, together with Bildung—above all, the first stirrings of love—actually played out atop the heights of uncommon abundance. It is infinitely easier to avoid the overestimation and the danger of possessions if one has had the opportunity to question the value of their fortune than if one has had to learn “to honor the penny.” At present, it is easy to see a reluctant grimace on the faces of highly intelligent people when one suspects them of considering compassion to be a particularly high moral criterion. The aversion to such a disposition [Gesinnung] extends so far that the object of suspicion feels as if he has been caught in the act of doing something indecent, unclean, a secret vice. He feels that if his partner sees their suspicions reinforced, sympathy will be at an end. —As for the ground of this peculiar phenomena? Anyone who sees his most valuable purpose in some highly questionable, and, in the most banal sense, needy creatures, thereby reveals a completely impoverished, disenchanted world of values. He is a skeptic towards everything one is required to recognize in good society—he is above all not a good socialist, because, to be one he would have to be the exact antithesis [Gegenteil] of the skeptic. But there are no skeptics today—every day, newer, higher values are discovered. One who appears to be a sated skeptic could, nevertheless, have just withdrawn into the last of these ultimate, concrete purposes—neither is he a dogmatist nor does he wish to become a skeptic. (Aren’t both of the same spirit? Isn’t the skeptic so unbearable precisely because he dogmatizes skepticism, just as the dogmatist does with one-day experiences?) One should seriously examine whether the authentic possibilities of a value-oriented life today are or are not just as poor for any one grimace-maker as the object of suspicion suspects they are for himself.

Entry No. 3 (9/12/1925)

In the midst of all the contempt one must show for enlightenment today under penalty of sinking low enough to join its good company, it is often admitted, rather condescendingly, that enlightenment has brought about some good for the justice system [Justiz]:

“Mais, aujourd'hui, si la philanthropie a fait à la société des maux incalculables, elle a produit un peu de bien pour les individus.”

“In our day, though philanthropy has brought incalculable mischief on society, it has produced some good for the individual.”

— Balzac, Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes. (1838-1847)

In the same breath, Diderot is praised as the greater at Voltaire’s expense. There are good reasons for this. Diderot may be artistically more or less significant than Voltaire, but, in a time of reaction, he is in any event more presentable. With reference to that “peu de bien,” however, some passages of their work should be mentioned without comment:

“(...) si donc le crime est de nature à supposer des complices, comme les vols, les assassinats commis par attroupements, et que, ni les témoins ni les preuves ne suffisent pour démêler le fil de la complicité, la question sera juste comme une autre peine, et pour la même raison.”

“Pensez que quelques minutes de tourments dans un scélérat (convaincu), peuvent sauver la vie à cent innocents que vont égorger ses complices, et la question vous paraîtra (alors) un acte d'humanité.”

— Diderot, Des Délits et des Peines (1798)23

“J’ai toujours présumé que la question, la torture avait été inventée par des voleurs, qui étant entrés chez un avare, et ne trouvant point son trésor, lui firent souffrir mille tourments jusqu'à ce qu'il le découvrît. Que le tribunal abominable de l'Inquisition renouvela ce supplice, et que par conséquent il doit être en horreur à toute la terre; [...] j'ose presque dire que cette horreur perpétrée dans un temps de lumières et de paix est pire que les massacres de la Saint-Barthélemy commis dans les ténèbres du fanatisme.”

— Voltaire, QUESTION, TORTURE. Dictionnaire philosophique. (1764)24

And how worthy of adoration his combination of goodness and spirit when he states (not defends!) in the same article that when the “Question” was posed to Ravaillac, Pamiens, and others, none complained, as the life of a king and the welfare of an entire state were at stake—but adds the following comment:

“Lorsque l'impératricereine demanda sur cet objet l'avis des jurisconsultes les plus éclairés de ses Etats, celui qui proposa d'abolir la torture, crut devoir soutenir que le seul cas pour lequel elle pût être conservée était le crime de lèsemajesté. L'impératrice lut son livre, et abolit la torture sans aucune réserve. Une souveraine a osé faire plus qu'un philosophe n'avait osé dire.”

— Voltaire, Ibid.25

And, one might add, qu'un autre philosophe n'avait osé penser.—Diderot once said of Voltaire:

“Il aura beau faire, beau dégrader; je vois une douzaine d'hommes chez la nation qui, sans s'élever sur la pointe du pied, le passeront toujours de la tête. Cet homme n'est que le second dans tous les genres.”

— Denis Diderot, Lettres à Sophie Volland [1762]26

Only, there is nevertheless one “genre” in which Voltaire is not second, and in which he stands a good head and shoulders above Diderot. This “genre,” moreover, is not unimportant for me in the least. Malgré tout!

Entry No. 4 (9/16/1925)

Immanence-philosophy [Immanenzphilosophie], any kind of “world”-view which equates “world” with phenomena of consciousness, or with the relationships between and functions of phenomena of consciousness, must have the courage to be solipsistic. Because whenever it takes for granted—and dares not deny—a pre-established harmony between you and me, or even just you and me as independent facticities, it has, at the most crucial point, declared its “world”-view to be a professional matter rather than the truth. One must not in any case resort to those underhanded and pathetic excuses of analogical reasoning, hypotheses, “necessary” conceptual-formations, by means of which they would spare themselves the risk. When one’s own consciousness appears as creator mundi, as creator of God and World and Heaven and Hell, it is no longer an object from which one might draw “analogical conclusions.” If this really were the case, there would be no need. Only when what is to be recognized as being [Sein]—or rather, what cannot be theoretically conjured away so easily—is already established before any philosophizing has begun; only then can the now-wiser “philosopher” draw up an analogy between his “naive,” world-constituting pre-philosophical consciousness… —or devil knows what magical operations the “naive” demiurgos reaches all his other poor, free-floating colleagues. Separately and privately, our philosopher feels, of course, that he is no world-creator, but simply another human being in the world; he imputes the idea of his essential being [Idee seines Wesens] to his own construction, which he calls transcendental consciousness; without this presupposition, analogy and all operations of its kind would be unthinkable. One must have experienced oneself as a human being among human beings before the conception of one’s own individual can emerge, and on the ground of which the existence of another, “similar” individual could first be inferred. In truth, however, not even the experience of being a human being among human beings is enough; rather, this itself presupposes the experience of being a human being in the world.

An immanence-philosopher [Immanenzphilosoph] will never come to see this. He is prevented from doing so by virtue of his scientific personality as a whole. Above all, the strange fallacy that because I must be capable of breaking the world down in analysis into sensory components, the world is nothing more than their composite formation, a patchwork of fragments of consciousness.27 But firstly, the word ‘consciousness’ loses all concrete sense when it no longer signifies the perception, the knowledge [Wissen] of a given world by a being [Wesen] living within it, but is instead inflated into the world itself and, further still, its creator—and secondly, the fact that in rational analysis we penetrate down into the substratum of sensory datum, or to what we know of them, says truly nothing about the construction of the real world! An analysis of consciousness, any kind of phenomenology, will always remain an affair of psychological specialist science, in the best of cases teaching us something about the composition of a tiny subsection of the world, namely, a part of our psyche, but cannot determine anything in particular about the being, sense, or content of their actuality. Wherever immanence-philosophy has truly philosophical aspirations, wherever it passes the slightest judgment on existence or non-existence, on our relationship to actuality, there is fraudulent acquisition [Erschleichungen].28 Lacking even the courage to declare the world, actuality (with the exception of itself), to be a mere phenomenon, the courage to be solipsistic—how could one love the proletariat, the poor, the masses!

I understand well enough that one might be a socialist because the existence of a petty-bourgeois and a proletarian class is unbearable, because it is unbearable that one must exist among such brutality, stupidity, meanness, and because bourgeois society necessarily involves the perpetual reproduction of this brutality, stupidity, and meanness, a necessity by virtue of its essence [Wesensnotwendigkeit], for without this it could not exist.29 But how one could prefer all this ugliness—even if it is conditioned more than ten times over by other factors than by its bearers—how one could prefer this ugliness to a single cultivated, civilized, refined, intellectual existence, to a single lovable woman: this is impenetrable to me; what’s more, in most cases, this preference is likely inauthentic, affectation. Where there is no spirit [Geist], no inspired life—there can, of course, be no will to change! Indeed, it is a fact that today the higher individuals stand on the left side of politics; that the right, at least in Germany, bears the aspects of spiritlessness, limitedness, and brutality upon its brow, that one can make no pact with it. It is also a fact that the right has the eternalization of social relations, and thus of their brutality, stupidity, and meanness, inscribed into its very program. But to love the masses for that reason! To give preference to the poor as such for this reason would mean preferring the proximity of an animal deliberately and maliciously smeared with filth by others to the proximity of an animal those others have kept clean. The little people are smeared with the filth of the digestive machinery of the bourgeois system of society, passed on in unbroken inheritance through education by the family, the school, and the press. With respect to ‘spirit,’ there are no class antagonisms, but only the antagonisms of the Volk, on the one hand, and antagonisms between the Volk and the person, on the other. Considered as a moral problem, the task is posed quite differently. For all that has been said here, still nothing has been asserted about what is to be done, but only a confession of what is felt. Under certain circumstances, it might very well be that one “should” clean up the excrement—but that does not mean it smells pleasant.

Entry No. 5 (9/19/1925)

A. Anyone who has experienced even once the variable weight, indeed variable meaning, of all sorts of basic principles [Grundsätzen] under a variety of different living situations will be wary of making prognoses about the possessor of certain basic principles solely on the basis of knowing something about some of the principles they possess.

B. Steady now, dear friend, you judge a bit too rashly. Would you entrust your life to an individual who declared the basic principle that human life is sacred to be absurd with as much ease as you would a member of Christian Science?

A. We have been speaking of basic principles. But by characterizing someone with reference to their membership to Christian Science, you have pointed to something much more central than those basic principles: namely, to the type of human being they are. And as far as their foil in your contrast is concerned, you apparently wanted to characterize him with greater clarity through your derogatory predicate “individual” than you could have by reference to his denial the aforementioned, philanthropic basic principle. To this I can only respond: it depends on who this “individual” is apart from his denial. I can come up with more than enough cases in which someone with such denial would appear to me a thousand times more sympathetic and trustworthy than an “individual” who not only does not deny the beauty of such a basic principle but even feels adamantly convinced by it.

B. You mean to say one would have to know whether he remains true to his other basic principles?

A. “Remains true”? According to our presupposition, we cannot know this, for otherwise there would be no prognosis to posit. Did you mean to say: “may remain true”?

B. Sure, you could express it in those terms.

A. Then my original claim was right: one must be wary of making prognoses about the possessor of certain basic principles solely on the basis you know something of some of the principles they possess. Knowing nothing but the basic principles of your “individual,” I would not know at all to whom he should be preferred.

B. But suppose that someone has the basic principle: to kill another for the slightest of advantages, if only he is safe from the danger of discovery!

A. Now you’re starting to get boring! —I know only to repeat what I said to your last example: It depends on who the concerned party is apart from that basic principle! —Your fallacy likely rests on the fact that, on the basis of experience in other cases, wherever certain basic principles come up, determinate types of human beings are assumed to be their bearers. Therefore, we often judge quite rightly in matters of practice. Besides, your last example is so unreal that I could even devise a story just as unreal to make a perfect lamb out of the man who has such bloodthirsty thoughts.

B. So basic principles have no significance whatsoever for the worth of a human being?

A. That, my dear, never even occurred to me to say. It depends what kind of human being he is. Yes, yes, I only repeat myself. For one the basic principles have significance, for another they don’t, i.e., for one they dissolve into the situation itself, for another they have a relatively heavy weight of their own, a fixed structure which holds up through the various situations and stations of life. And perhaps it is even possible that basic principles have a power of their own, and the capacity to shape human beings to a certain extent, depending on who they are and what they are like. But that’s for another occasion!

B. I have the feeling that somehow or other, you’re about to make another concession to me.

A. Possibly! One should never take another at their word in such things. And that is what I wanted to say at the beginning! Good night, dear B.

B. Until next time!30

Entry No. 6 (9/25/1925)

The epistemological question about the reality of the external world necessarily results in a circle. For even in the more cautious framing: “First, we want only to show what we mean by ‘reality,’” existence—and indeed the enduring, uniform significance of that which exists—is already presupposed as material evidence. What’s more, I say to Cornelius: If one treats reality as a concept to be clarified and discussed in connection to the doctrine of things, one may not afterwards speak (with an aftertaste of metaphysics) of the (unconditioned) reality of consciousness. So far so good: in the instant I have a sensation, what gives me the right to ascribe “being” to it? A confusion by virtue of the use of language: “I sense something.” This “something” can never signify anything! What is meant is: I sense, and the distinctions of sensations, their qualities, are first introduced by us ourselves; they do not inhere within this sensation at all, but are merely relationships to other sensations. Thus with regard to the phenomenal, what is said is not: “I know of something,” but at most only: “I know” [“ich weiß”]. It is an equivocation to apply transitive knowledge to both spheres, to that of things and that of phenomena, and to believe that one can “reduce” the former to the latter—it concerns something completely different. —This error then draws out Cornelius’ central error, that of the circular justification of synthetic a priori judgments. Where no fixed objects are given, no synthetic a priori judgments can be given either. —Our consciousness is a problem, it has yet to be unravelled—conversely, cognition [Erkenntnis] cannot be “clarified” by indiscriminate reference to the data of consciousness.

Entry No. 7 (9/27/1925)

There is one fact I cannot get past, and it seems to me the most dangerous one of all to trust in the existence of absolute truth: that all evaluation, all interest, all affirmation and negation seem to be in so great a measure dependent upon situation. Beyond the question of whether the sight of life-threatening dangers may in fact entirely recreate the world around you; beyond the fact that in fever, in drunkenness, in every kind of ‘exaltation’ a view of the world creeps in which, afterwards, “normal” consciousness tacitly, self-evidently, and immediately corrects and forgets—someone might doubt whether madness does not have a method of its own, just as legitimate or illegitimate as that of “soundness” of mind. Primitive peoples seem to live in remarkably similar environments to those of the mad. Therefore, it all comes down to knowing whether the holy devotion of martyrs, or rather the strength to safeguard one value until the soul’s last flicker, letting nothing displace it—whether this is truly an example which triumphs over our doubt, or over any particular kind of narrowness, stubbornness, madness, remains to be seen. I am no skeptic, and I am decidedly on the side of belief in the one Logos, but it is quite unnerving that even the partial inactivity of the brain in a dream can stand everything on its head.

Entry No. 8 (10/10/1925)

Where are the feelings, the actions, the entirety of one’s life tucked away when they have fallen away and not a human soul knows any more than this? One day, all there is might be no more—nothing at all—as if it never had been at all. Just people laugh when old inmates of a poorhouse tell and outdo each other in telling stories of how well they once ate, which princesses they loved, how beautiful they once were themselves! And so every single instant, chance encounter, the joys and sorrows of the days of one’s youth and one’s strength shall fade, be totally extinguished, with the passing of youth and the passing of strength! —Look to the eternal—so your night needs no light borrowed from days past! But where is the eternal, wherein I am not in vain, wherein I rest from my weariness and fear of the truth, wherein I no longer deceive myself, as one does a crying child, out of pity. Pity for oneself, weariness at thinking, longing for a halt, weakness—and the bourgeois pseudo-security in everything spiritual which results from this. May it never be so! —Problem of the eternal in the concrete, of the “fulfilled” life.

Entry No. 9 (10/20/1925)

Kant ties our relationship with the absolute to action and our knowledge [Wissen] of being the conscience [Gewissen] which accompanies our action. But conscience “speaks,” it has the capacity for logic, it can be comprehended by the ethical maxim. Even our relationship to the absolute granted through our actions, through our life, i.e., the “meaning” of this life, can be expressed—albeit indirectly, in analogies. This is an ontology. In the pure, epistemological philosophy, this falls away, hence the dissolution of all and each into nothingness. The theoretical precondition [Vorbedingung] for this lies in overlooking the function of the doctrine of ideas [Ideenlehre]. The deduction of the concepts of the understanding [Verstandesbegriffe] is accepted, but not in the case of the ideas. Thus, reason [Vernunft] is simply equated with the understanding [Verstand] and all becomes meaningless apparatus. For only the concepts of reason [Vernunftbegriffe] can give meaning, they alone connect science and life. To accept Kant without the doctrine of ideas means to give everything over to mere appearance; at best, to suspend the sole in-itself, an apparatus senselessly clattering away, in total nothingness—what a beautiful philosophy!

Entry No. 11 (11/13/1925)

University business, official function, takes me prisoner. Beware, beware, beware! There is nothing more ridiculous than the sense of importance such business would impose upon you and enforce through you. Unveiling the threadbareness of this gravitas may be the sole task philosophy can fulfill—or is, in any case, the presupposition for all further instruction in philosophy. Most proudly declare their official function a “mere concession;” but this only shows you the extent of what is, at the very least, their self-delusion [Selbsttäuschung]. To ensure your own official function does not remain mere concession but ceases to be one entirely, it must be performed one each occasion as the object of a still more alert irony. The means is always and everywhere the transition from fetishism to more concrete, anxious concern, from seeming to being [vom Schein zum Sein]—starting, most often, from reflection on semblance itself.31 But being is everywhere too, only difficult to grasp because it has disguised itself a thousand times over: not out of social interests, but within social interests themselves. This is, however, not merely a regrettable accident, a mishap, but necessary. Semblance can never be overcome by simply “seeing through” it; indeed, one might question whether it should be overcome at all. In truth, releasing the disguised from its disguise, unmasking it, is not always of value, not even necessarily for theory; rather, becoming more, better becoming, becoming more decent, becoming more truthful, is what matters—and it is only in this sense that unmasking, that unveiling make sense. In so assuming one’s official function, it may even become pedagogically relevant—but again, only in teaching attention to grounds, not for the sake of the grounds themselves, but for the sake of their development, for the sake of their objective connection to life. But wherever official importance does not brutally annihilate itself through reflection upon itself, it is not so repulsive because it is a veil over some being of little importance, over this being’s truth, its true unimportance, but because the veil of importance is itself a repulsive being. Philosophy does not concern itself with concepts alone, but with what they mean. “Truth for the sake of truth”: nonsense!

Entry No. 12 (3/13/1926)

In order to comprehend a human being correctly, one must view their life as an arrival, as an emergence into light from out of an eternally and terribly dark journey, which infinitely many beings from infinitely many places have undertaken, but of these only this one, singular, individual human being, born in that place on that day in particular, washed ashore into the light, only to be caught and washed away by the same dark waves in the near future. The life of every individual, determinate, here-and-there existing human being with this determinate name must be viewed in this way, and not in view of some philosophical fiction of an abstract human being “in general,” but before anything else in view of one’s own life through each waking instant—the present, the next, and all thereafter. In light of this, everyone appears as the heir of endless, dull, errant, inscrutably motivated efforts, as an incomprehensible success amongst numberless failures. Waking each morning is a symbolic repetition and exhibition of the miracle—and not only a symbolic one. But it is precisely because of the enormous responsibility which seems to weigh down our existence as a heavy load as a result of such insight, the burden of which threatens to outweigh the insight itself—or, rather, despite this semblance [Scheines] which accompanies it—we must not accept any superstitious-mystical consequences as valid. The proposition that we are responsible, that we owe the balance of this account, stems from the darkest church morality, is delusion—a fetish intended for the stupid who have been led around by the nose with it for centuries, diverted from their actual interests—is pure ideology.

All that is superstitious-mystical, dogmatic, ecclesiastical, all which would burden us through authority and mysterious intonation, every sort of sentence which demands a “vision,” a “grace,” an “inspiration,” we must chase them away with laughter, because our arrival into light, our life, is such an incomprehensible, one-off affair, such a perplexing success, an arrival at such an indescribably desirable station. We would not be among those fools who let their stay go to waste by lingering in the “house of worship,” that world of semblance [Scheinwelt] which becomes all the more dissembling [scheinhafter], all the more ideological, aggravated, zealous and gullible by those who imagine it the “actual” one. It is an old trick of the enemy and in particular of the tradition of the power-greedy to seize and reappropriate the weapons of the heretic. Since the beginning of the world-historical process when the philosophy of the heretic became ancilla theologiae to the Czarist’s cry for freedom of the press, superstition has always stolen from its mortal enemy, reason, and so there’s nothing out of the ordinary when the “religious” steps enters the field of battle against our “dogmatism.” The religious will triumphantly unveil our concept of the dark wandering—the grand endeavor, the perplexing success, the human being as such an “heir”—as a superstitious clubfoot [Pferdefuß] and sneeringly ask about the “actual” interests we so forcefully defend. But we should not allow ourselves to be taken aback by this. Every individual human being stands before us, or ought to, not only as “heir” but also as “proxy” [Anwalt] of those numberless efforts and grand endeavors; the eyes of animals and, moreover, the eyes of all those throughout the class strata of human beings whose humanity is so forcibly atrophied today (prisoners in both the literal and figurative sense) are more than just a theoretical reminder of this. We are happy to argue the details of this, to discuss the affinity between our concepts—Schelling’s “Odyssey,” Schopenhauer’s “Will,” and, for my part, death and apocalypse.

But when it comes to the “actual interests” we are intolerant and we make it “personal.” So long as the lives of animals are so forcibly cut short, so long as the unfolding of the most real and most fundamental possibilities of human development is so violently cut off, so long as the “grand endeavors” and “numberless efforts” are thwarted not in the nether regions of metaphysics but here in the immediate present, so long as a philosophy of the motto man does not live by bread alone spreads in a world which yet denies bread to human beings and animals alike, we will ask the philosopher who spreads it about his own hunger, or at least about his apprenticeship in the mines. And this is materialism, insofar as our perspective divides hunger, love, health as actualities from all values whose validity rests on social convenience. Indeed, this is even idealism, as its bearer feels solidarity without individual need to, appearing as “heir,” as “proxy.” In this idealism, it is not so unmaterialistic as the Marxist who foregoes the reality of the individual under the concept of class, and propagates the class morality [Klassenmoral] that the individual must be prepared to sacrifice all for a future one will not live to see, but without having any intimation of its Christian fundamentals. On the other hand, of course, our metaphysical “clubfoot” is a model of self-consciousness. —Though it bestows no responsibility to speak of (for to speak of it would be ideology), what tremendous significance each fleeting day assumes! And, in tandem, the feeling of being an heir, a careless heir who squanders their inheritance without knowing what it is they do! Therefore, confront within oneself and others all ideological hiding places, for these make fools of us in the most pathetic sense. You are—through the happiness of your life, and freedom, or the possibility of it, in your reason—the hope of every creature, those you know and those you don’t; everything has waited and still waits for you, you yourself have longed for this very instant from eternity—and do nothing; and dream it away. But what is to be done?

Entry No. 13 (3/17/1926)

This is perhaps the most distinctive feature of the products of modern ideological reaction: they wish to bring “consciousness,” “reason,” “thinking,” “sense,” into disrepute; in short, all that is clear, which lies in the open, freely available, the sphere of possible understanding, of belonging. And this is what they all share in common: they ground their assertions on a vision, an intuition, a revelation which is not subject to any criteria; these grounds, the critic lacks, while the man of reaction has been granted them one and for all by special dispensation of “grace.” This spectacle is not just the grotesque mirror image [Widerspiegelung] of an imperialist world in which real privileges are really seized and really serve to harm humanity, but in fact presents the apologetic of this very state of affairs. Though in itself merely comical, the procedure through which each of these beloved “philosophers” (Rudolf Steiner, Scheler, Sombart, e tutti quanti have all professed to!) is supposed to envision the true “essentialities” [Wesenheiten] in actuality means: everywhere there are chosen ones, the select. Ford is eternal. Scheler and Spengler in philosophy, Ford in automobiles, the latter as material basis of the former. In the discrediting of intellect, the youth are prevented from illuminating not only this connection, but also other, much more crucial and much more sinister ones. The old idols, “belief” in the sacredness of a whole range of “ideal” contents which have been dissolved by analysis—“vision” is supposed to rescue even them. In theory, all of these undertakings live off the morsels they snatch from the table of their enemy, the “Enlightenment”: that ultimately all concepts must prove themselves in intuition, which is evident in itself, and, furthermore, that the values according to which our lives are directed are pregiven in (or as used to be said: residing in) reason; that there are authentic and inauthentic values—the old doctrine of natural law in cramped, garbled, romanticized form.32 They are irrationalists to the extent they emphasize the sheer givenness of values, rationalists to the extent they wish to impose their reactionary “insight” on us as universally binding, and pathetic enough to know nothing of the history of their own “ideas”—not to mention their own concrete history! —One must restore honor to “consciousness,” “thinking,” “reason,” and whatever else illuminates!

Entry No. 14 (5/20/1926)

Shortness of memory—especially when it comes to the ephemeral security of everyday life—is at the root of the intricacy of life. There, in the light of your sheer existence, it’s all there, all in hand, the one great, singular opportunity like an island in eternity, and you no longer even recall your childhood. And if you do happen to think about the future, it’s in the most petty bourgeois philistine [spießbürgerlichsten], limited way. Sociology, psychology, philosophy—as sciences for unmasking one’s own conditionality, one’s own petty bourgeois philistinism [Spießbürgertums]! Lose the blinders of everyday life—you must overcome shortness of memory! (If this is achieved, I doubt the theistic categories will reappear.)

Entry No. 15 (6/3/1926)

The error of all psychologism in all immanence-philosophy can be expressed most clearly as follows: First, the immediate given, the phenomena (however one may conceive them), are determined to be the sole legitimate source of conceptual meanings. But then—after the concept of “reality” has also been determined in such a manner—the whole world of phenomena (viz., absolutely everything) is unexpectedly snuck into a rather small corner of itself, “one’s own consciousness”; which, for example, is confronted by strangers, and a mechanism must therefore be devised by means of which this impoverished “consciousness,” which might possibly still be equated with the sum total of sensations and their relations, should be able to spin all of this out of itself. And suddenly, this non-concept [Unbegriff] of “one’s own consciousness” appears to be the sole thing which is endowed with absolute “reality,” a “reality” which no longer has anything whatsoever to do with what has previously been so beautifully established. Epistemology (or rather a part of it: the analysis of meaning) becomes psychology, and psychology becomes metaphysics. Yet, according to this approach, the reality of one’s own consciousness must not have the slightest advantage over things or even other consciousnesses (see also September 16th, 1925).

Entry No. 16 (7/1/1926)

The kernel of truth in Husserl’s critique of relativism: if there is to be judgment-like truth, then there must be intelligible contexts of justification which subsist between all of the laws of logic as much as between “truths” in general. As soon as the laws of logic themselves are justified by judgment-like determinations about any facts whatsoever—that is, by other sciences—a circle thus arises: either the validity of logic is absolute and self-enclosed, or there is no measure of truth in judgment at all. —So much for the “kernel of truth,” but what of this determination itself? Is logic truly so comprehensive? One must reflect on the one who reflects in this way! Then, however, it becomes clear that one’s faith is everywhere at risk, and do I not, in the end, prefer the paradoxical bearing of Kierkegaard to the ridiculous metaphysical tricks of the metaphysical “minimums” of our otherworldly philosophers and physicists! I would rather—malgré tout—believe in the existence of God and the devil than in the “mass of sensations.”33

Entry No. 17 (7/9/1926)

To the extent the talk of “bonds of blood” is supposed to have normative character, and even one-sidedly backgrounds the old patriarchal idea of “obedience,” it belongs among the darkest idols of ideology. A false shame, repeating the self-evident, all-too-often stops those who know from even mentioning a topic which has, at the very least since Montaigne, become unproblematic in modern times, and which Democritus had already treated with sufficient clarity. This, and the fact that the remnants of petty peasant production still seem (erroneously, and only to those on the outside) to lay material foundations for such a patriarchal ideology, as well as the tastelessness of some younger playwrights, shuts up within closed mouths the insight which could already be considered ‘historic’ by Ibsen. —But one should not let the self-evident, that is, what has become fully ripe, rot on the branch; ideologies endure for hundreds of years after they have lost the breadth of their former foundations! —I, too, might take all-too-much to be “self-evident,” but I cannot let myself forget the dark, malicious egoism of my mother and the petty, cowardly egoism of my father would have ruined a thousand others, not just me. I cannot let myself forget that there is no stupidity or meanness which these people would not have mobilized against me—that they would have murdered wife and friend of mine alike a thousand times over out of the most ridiculous and “outdated” fanaticism in the world, if fear over legislation in a society socially progressive enough had not bound their hands; my mother: active and evil; my father: the cowardly, docile attitude of the petty sinner and henpecked husband. —The thought that what I write here is exaggerated by affect, and that psychoanalysis along with individual psychology are to be applied to it; the thought that any fourteen-year-old boy could talk just so—none of this should hold me back from being clear. Perhaps the fourteen-year-old is nearer to the truth; only those completely lacking in orientation could believe psychoanalysis would blur the objectivity of this judgment. —I cannot allow myself to take the self-evident as too self-evident. I cannot allow the traditional atmosphere to smuggle in the mood there could be anything other between my parents and I than an unbridgeable, yawning gulf which cannot, in fact, be filled.

Entry No. 18 (7/10/1926)

Quantitative expansion of one’s reservoir of memories available for recollection is not itself the same as learning and making progress. Filling those old drawers—in this respect Bergson is entirely correct—is no increase in cognition.34 Never growing old—always seeing totally anew—always formulating another question—ability to marvel at one’s own position—is the attitude of the learner.

Entry No. 19 (7/21/1926)

How unreal and lost to us the most decisive holdovers from lives past can be in a change of situation—for example, in a hospital room, in total isolation. In contemplating that which is “actual,” one ought at least investigate its actual contents for such a possibility; though not a remotely reliable criterion, it is, perhaps, not entirely fruitless; unreliable, that is, because neither the fluctuations of consciousness nor the diseases of memory and imagination constitute a yardstick for measuring the order of things.

Entry No. 20 (7/26/1926)

Imagine you, yourself, nod off, never to be seen again, and, at the same instant, wake up as some other inhabitant of earth, with gifts corresponding to yours but without any recollection of your only just concluded life. But then someone comes along and relates to you, down to the smallest detail, the thoughts, cares, deeds, and intentions of the deceased. How terribly little all of this would interest you then! —How little we do has a significance extending beyond our incidental and petty sphere! —Not just sub specie aeternitatis, but even sub specie the slightest transformation or change in aspect, our life tends towards utter insignificance. (Is there anything that could be more paradoxical, more rebellious, than human love, which consciously takes this upon itself?)

Entry No. 21 (7/30/1926)

In order to see how difficult it is to “understand” our fellow human beings, we need only recollect how pale and abstract the joys and sorrows of our own daily lives appear to us after only a short time. A mere two hours after having painstakingly achieved some result, the exertion it took to get there might already seem negligible and unreal. How much more true this is when someone recounts to us theirs!

Entry No. 22 (11/18/1926)

The bearing of the individual depends entirely upon certain articles of faith; even science falls back on them. There are no guarantees to be given in the manner of insurance agencies; rather, one actually takes this risk upon themselves. Hence, universal validity is always a dubious affair. But one ought not overlook that we have been given a relative universal validity and capacity for understanding, especially with respect to more “tangible” things. Wherever judgments lose their relationship to the sphere of tangibility—the sphere of terror and of death, as much as happiness—or are only “applied to it,” there ideology and idealism arise, and one becomes “Märtyrer am Stoff” (Husserl), i.e., to nothingness.

Entry No. 23 (11/26/1926)

No doubt about it: Freud was right to make the whole of civilization dependent on the fact of repression. We find confirmation of this—in a certain sense retroactively—in two places: in the indifference of all interests relative to the libido in its (after the original repression) relatively primary form of the sexual drive—and in the qualitative affinity of every kind of “spiritual” satisfaction with that relative primary and particularly pregnant one. Anyone who has sufficient consciousness will have felt in such an instant that all “highest” satisfactions are but a pale reflection of this “most natural” one. —But one must not forget all this is to be understood only in an allegorical and figurative sense, for the truly original situation may only ever be “repeated” in second editions.35 In this transference [Übertragung], in this second edition, the social plays a greater role than Freud and his school have noticed to date. Even the identity of the one who gains certain insights and the one who later maintains and conducts themselves in accord with those insights is more a matter of convention than reality. The legitimate pride of the old scholar who can boast: “I discovered this!” and his narration the following evening which recounts the circumstances of that discovery are all-too-similar to those photographs of her youth according to which our old aunt was once the most beautiful maiden. —Even better than stacking up one’s discoveries, the photographs of one’s youth, is physical training. That way, at least, you have the prospect of staying alive as long as possible to look forward to. Alba writes different numbers with six fingers at the same time, Diebel sweats blood, Pavlovna dances: this is conscious, energetically pursued training. Intellectual production is no exception. Of course, without content there can be no thoughts, but the extent to which the givenness of content, the extent to which “Intuition”—that is, not just the formal moments of intellectual production—can be brought about through systematic training, still has yet to be investigated. In composing, tightrope walking, and thinking, practice does more than you might assume.

Entry No. 24 (12/10/1926)

One must never take theories absolutely. Theory in general is a historical entity, conditioned in manifold ways. Wherever theory does not serve, but rules, wherever it does not serve human beings—there is distance from life, close-heartedness, close-mindedness. Perhaps the whole scientific crisis of the present results from the fact that, on the one hand, natural-scientific calculations are considered to be absolute propositions and, on the other, natural-scientific theses are considered to approximate actual insights. In the concept of theory itself, everything has been intermixed and muddled. The theory of kinetic gases and the theory of redemption—this “and” is the reverse side of our science. — But here, there are only two possibilities: Either Hegel is right, and there is a system of reason and this is the truth, the whole of truth, and the truth of any one proposition is legitimized solely by its position in the context of that whole, in which case there is a truth in theories, and in which case theories are true in general. Or, there is no such “whole,” in which case science makes its calculations and it is up to God—or, as far as we’re concerned, the devil—whether they are fulfilled—and authentic insight belongs only to concrete personal life and can be propagated, but not taught. Theory, that grand word of the age for 150 years now. Theory, just as the machine, is infinitely precious as a handmaiden (but then it could not really be called theory in today’s exaggerated sense of the word!), and an evil demon as an end-in-itself. — Hence the trickiness of all who “swear by a theory.” Above all, the religious and political sects. Christian Science, National socialists, Anthrosophists, Marxists, Psychoanalysts, Cultural morphologists, Phenomenologists—in this respect you are all alike, you who lead a life which can be summed up into such a word: it is not you that has the theory, but the theory that has you—and you don’t even rightly know what has you: namely, what a theory is!

Entry No. 25 (12/18/1926)

Graphology, characterology, psycho-physiological constitutional research, etc., need not be consciously deterministic. In order not to be, they must be made to agree to put before each of their bloviations:

The essential [Wesentliche] eludes us. We ignore it. What follows is valid only insofar as what is crucial in human beings does not make itself known. That which is decisive, that which is most evident, appears to us a miracle—even as coincidence.

If they cannot agree with this presupposition, they must be Hegelians or naive. Perhaps they derive their significance and influence from the fact that what eludes them as “miracle” is rare enough in our time to appear as one.

Entry No. 26 (2/2/1927)

If I were asked what quality I am most attracted to in a person, I would immediately have a clear notion of it, but find myself at a loss as to how I would describe it. Concepts such as unconditionality, inner resolve, honesty, consciousness, dependability are all much too formal. There is something highly determinate in between such moments—or rather, when I attempt to analyze this determinateness, I confront such generalities. Essential above all is the unambiguous and unmediated relation between an authentic feeling and all acts of judgment and will of the person I am supposed to value. The more conventional evaluations, legitimized only by tradition, insert themselves between original striving on the one hand and thinking and acting on the other, the more unsympathetic this thinking and acting is to me. Of course, the concept of this “original striving” has yet to be clarified. If I, at first, put down that its true goal is truth in the intellectual sphere, it becomes clearer that the objection that this “original striving” is, as with Schopenhauer’s blind will, always oriented towards the crudest material, must at least be qualified. Rather, I believe that striving for greater possessions in property, social prestige, and power are not original, but conditioned by purely conventional, inexperienced, clichéd judgments, as their bearers arouse only disgust. It becomes painfully apparent: they are just that dumb. In an entirely determinate sense, the person whom I am to respect must be intelligent; in the questions which are decisive for his character, he must not be ideologically duped. This is not to be confused with a demand for breadth of knowledge (definitely not that!), nor with general worldly wisdom, nor even with any kind of education; quite the contrary, as all of this under the present circumstances—that is, if it does not become a means, a weapon, of the kind of intelligence I mean—only acts as inhibiting. This may be illustrated, perhaps, in a sentence such as: authentic interest must have the power to unmask all mere ideology. And perhaps this is even the criterion for distinguishing true passion and fanaticism: that in the case of fanaticism, the pure truth becomes as powerless as ideology. The distinction between a truly loving woman and a pitiable fool of one is nowhere better proven than in the fact that the latter spurns her true friend to run after some windbag, whereas the former sticks with their true friend in the face of a thousand windbags. To side with truth against the world, and thereby to thine own self be true, is the highest virtue, and for this intelligence is required; to side with untruth, to serve it, against that same world, is the worst of all sins, and for this obsession is required. Whether you are true or untrue to the world—from this alone, nothing can be concluded.

But here is the kind of intelligence I admire! In objective terms, in what does it consist, what does it achieve? Some wrongly call it “instinct,” which they flatly oppose to flattened science, while this distinction between instinct and science obtains just as much within what I call intelligence as it does within the bourgeois sphere. But while in the case of the latter I relate both instinct and science to the mere establishment of facts (facts which science in this sphere fixes conceptually, orders, arranges in relationships), intelligence, in instinctual as much as in scientific form, consists in the comprehension of essential connections through the facts themselves. Whether a child judges “instinctively”—for example, my mother tells me God wants be to be obedient because she herself does not want any more trouble out of me—or whether a researcher seeks to get to the bottom of the laws of emergence of Totem and Taboo in primitive peoples, in at least this respect it is fundamentally irrelevant: for, in both cases, the focus is not on the facts, but rather, in a certain sense, through them. This “intelligence” is, in fact, based upon “knowledge” [Wissen] overall, but the degree of the former is in no way dependent on the mere breadth of the latter. No matter how much one ‘knows,’ they may still be terribly stupid, and vice versa. The simplest maid and the most uncultured proletarian may demonstrate the highest intelligence where it matters to them, without thereby becoming a single ounce more “cultured.” Whether formal education may awaken intelligence and how—is a highly important question. But even more important is the question of how genuine interests can be awakened, for these are the most powerful motor of intelligence, and vice versa, in their reciprocity. In any case, all of those qualities mentioned at the beginning—unconditionality, inner resolve, etc.—are meant only in the most intimate connection—perhaps as much ground as consequence—of this intelligence. The antithesis of what I respect: Lucien de Rubempré in Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes—in large measure corresponds to what has been said; also, Esther and Mme. de Sérizy (although naturally not to the same measure as Esther).36

Entry No. 27 (7/26/1928)

Morally inferior human beings have protection in being equally inferior in all of their expressions, down to the smallest. The critic who confronts the sneer in every expression of life then immediately appears as the resentful, petty one, who looks suspiciously at even the most “harmless” of statements. So, in the face of the bad, even that which is most decent becomes so bad it finally falls silent, whether for its alleged “injustice” or for want of that which is good.

Entry No. 28 (11/22/1928)

I would like to know whether there are those among the poor who actually evade the capitalist spiritual order. By this, I understand human beings who, even in the event they came into success, would remain, in their actions and evaluations, capable of the honestly revolutionary mentality of the declassé. Thereby I would know whether success is, in the end, truly omnipotent.

Horkheimer, “[Verstreute Notizen] [1920-1923],” in: Max Horkheimer, Gesammelte Schriften. Band 11. Nachgelassene Schriften: 1914-1931, ed. Gunzelin Schmid Noerr (Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, 1987), 233-236.

Horkheimer, “[Philosophisches Tagebuch] (1925-1928),” in: Ibid., 237-261.

Marx, “Foreword”: “Real humanism has no more dangerous enemy in Germany than spiritualism or speculative idealism, which substitutes speculative “self-consciousness” or the “spirit” for the real individual man and with the evangelist teaches: “It is the spirit that quickeneth; the flesh profiteth nothing.” Needless to say, this incorporeal spirit is spiritual only in its imagination. What we are combating in Bauer's criticism is precisely speculation reproducing itself as a caricature. We see in it the most complete expression of the Christian-Germanic principle, which makes its last effort by transforming ‘criticism’ itself into a transcendent power.” In: Marx & Engels, Collected Works. Volume 4. Marx and Engels: 1844-45. Translated by: Richard Dixon and Clemens Dutt. (Lawrence & Wishart [Electric Book]; 2010), 7.

The Holy Family was only published in full in 1932, in MEGA(1), which Horkheimer cites throughout the 1930s: Marx-Engels-Gesamtausgabe. Abt. 1, Sämtliche Werke und Schriften mit Ausnahme des Kapital, Bd. 3: Die heilige Familie und Schriften von Marx von Anfang 1844 bis Anfang 1845. Marx-Engels-Verlag, Berlin 1932 (Reprint Auvermann, Glashütten im Taunus 1970)