Collection: Society and Reason (1943-1947)

Transcriptions and translations of previously unpublished materials from and around Horkheimer's 'Eclipse' (1947)

Table of Contents.

Editor’s Introduction: Eclipse as “Prolegomena” to the Dialectic.

I. Possible Topics. (Jan.-Feb. 1943).

II. Notes for Lectures I-III (Late 1943).

III. Letter to Pollock: “On problems of Scientific Style” (Nov. 1943).

IV. Lecture II: On the Domination of Nature [First Draft] (Late 1943).

V. The Revival of Dogmatism (1943).

VI. Society and Reason. Lectures I-V (Spring 1944).

VII. From Society and Reason to Eclipse (1944-1947).

VIII. Lectures on National Socialism and Philosophy (Spring 1945).

Editor’s Introduction: Eclipse as “Prolegomena” to the Dialectic.

§1. Revising Society and Reason.

This collection features original transcriptions of manuscripts from Horkheimer’s sequence of five lectures delivered at Columbia University in Spring 1944, between February 3rd and March 2nd, under the title of Society and Reason (hereafter: S&R). The manuscripts for these lectures would serve as the basis for Horkheimer’s Eclipse of Reason (hereafter: Eclipse), published in 1947 through Oxford University Press in New York.1 Eclipse was the result of nearly three years of extensive revisions by remaining members of the ISR. By the mid-1940s, the core had been reduced to five: Max Horkheimer, Theodor W. Adorno, Leo Löwenthal, Friedrich Pollock, and Felix J. Weil. These materials were sourced from the digitized portion of the Max Horkheimer Nachlass (hereafter: MHA, for Max-Horkheimer-Archiv),2 likely compiled around the time Alfred Schmidt began translating Eclipse under Horkheimer’s direction, published in 1967 through S. Fischer Verlag in Frankfurt, am Man, under the title Zur Kritik der instrumentellen Vernunft.3 With the exception of many of the letters included below—as well as the fragment “On problems of scientific style” (1943), excerpted from a letter written to Pollock in 19434—few if any of these texts have been published in part, and none, to my knowledge, in full. This is all the more surprising because most of the material was originally written (or dictated and typed) in English. This makes the composition of Eclipse unique.

In a letter to Gertrude Isch, 3/29/1946, Horkheimer distinguishes between Eclipse and his ongoing philosophical collaboration with Adorno, still named the Philosophische Fragmente (hereafter: Fragmente) at the time, by connecting the respective language in which each project was composed to its intended audience and to its systematic position within their joint ‘philosophy’ as a whole:

My external life is very monotonous. I mainly study philosophy, which, as you know, I have always considered to be my real reason for existing. Since the Institute is still affiliated with Columbia University in New York and I also maintain contacts with other universities and institutions, my work is occasionally interrupted by travel, the writing of long minutes and “memos,” and tedious correspondence. From time to time I give lectures at the university where I teach so as not to lose contact with the new generation. I have also written a little book for students, which is due to be published in the autumn! Nevertheless, my heart belongs to philosophy. What I write in this field is intended for a few readers and appears in mimeographed form or in very small editions. In doing so, I stick to the language of philosophy, German, even though Herr Hitler has degraded it to jargon and disfigured it beyond recognition. He himself perverted the German language in Germany, but since many emigrated intellectuals also betrayed it, this language has only been able to survive outside your beautiful country with a few loyal followers, some of whom work on the beautiful Pacific coast of California. My closest collaborator is Mr. Adorno. In him I was lucky to find a person who uses his universal education for the passionate pursuit of truth, something that has become rare today, since the two almost always occur separately. I do not know whether he was in Geneva when you worked for me. Now he lives not far from us in Los Angeles and shares my ideas and interests.5

At the time of the letter, the Fragmente had only received a limited printing of several hundred copies in the format of a mimeograph in 1944, and would not be published until 1947, by Querido Verlag in Amsterdam, under the title of the Dialektik der Aufklärung (Dialectic of Enlightenment, hereafter: Dialectic).6 Like the Dialectic, Eclipse was the work of a collective. Without the combined and sustained efforts of Löwenthal, Norbert Guterman,7 and, last but never least, Adorno, in editing and revising the text, it is doubtful that it would ever have been published in any form. In January 1945, Horkheimer wrote a letter to Adorno informing him that Guterman had already begun to oversee preparations of the manuscripts for publication. Horkheimer ends the letter by asking Adorno to send some revision notes at his leisure: “I think it would be a good idea for you to jot something down the additions you had in mind. Should you not have time to get around to it, however, we will just let the thing go to print as is.”8 Adorno’s response was anything but leisurely. Löwenthal and Guterman would soon be made responsible not only for translating and integrating drafts of Horkheimer’s later additions, but also doing the same for Adorno’s substantial ‘inserts.’ From March 1945 through January 1946, just weeks before the submission deadline for the manuscript, Adorno would send a number of lengthy memoranda to the editorial team with “countless formulations for minor additions and small changes” as well, the longest of which was 37 pages in length.9 As was typical for their writing process since the early 1940s, Adorno and Horkheimer would meet in person to discuss the manuscript intensively and generate new lists of changes and ideas each time to send to Löwenthal, who would then have to sort out the redundant suggestions and confirm whether he was supposed to countermand or ignore conflicting directions.10 A month before the manuscript was due, the book still had no title. Horkheimer provisionally christened it Twilight of Reason, which he considered ”too pessimistic” and too reminiscent of Wagner’s Götterdämmerung. Eclipse was first proposed as an alternative by an editor at Oxford University Press in March 1946 who needed to fill in a title on a form the publisher needed to begin the process of typesetting proofs.11 There were two peaks of last-minute panic in 1946: the first lasted the month of January, during which Horkheimer would rewrite the entire ‘Preface’ from scratch, express grave reservations about the structure, and send a “massive telegram to Löwenthal and Guterman with detailed instructions for the incorporation of large excerpts from Horkheimer’s unpublished essay “On the Sociology of Class Relations” [1942/43]; the second spanned the early fall months after Horkheimer received the proofs from the publisher, during which Horkheimer would ask Löwenthal if they could reset the entire book and express crippling anxiety over the deficiencies in its literary style. Löwenthal had to beg Horkheimer:“Please do me the favor and enjoy the completion of this work.”12 While Horkheimer’s anxiety was certainly compounded by the headaches of Anglo-American academic publishing, it had a much deeper source, one which accounts for why he found (and made) the publishing process so needlessly difficult.

§2. Task of the ‘Prolegomena.’

The process of readying Eclipse for publication was excruciating for nearly every party involved. (At one point, Löwenthal compared it to Hegel’s schlechte Unendlichkeit.)13 It’s not surprising Horkheimer mustered so little enthusiasm for it in the letter to Isch, even to the point of contrasting it, ‘a little book for students’ of lectures he gives ‘from time to time […] so as not to lose contact with the new generation,’ to his efforts in ‘philosophy’ proper, and to which his ‘heart belongs,’ in ‘the language of philosophy, German.’ A month prior to the letter to Isch, Horkheimer writes Löwenthal in early February that the purpose of book was largely pragmatic: on the one hand, “it would help to establish relations in Europe” as the ISR looked into establishing a new ‘branch’ in Frankfurt after the end of the war, and, on the other, it would relieve some of the pressure Adorno and Horkheimer had felt to rush the finalizing and “distribution of the Fragmente.”14 But it was clear that Horkheimer held Eclipse to a much higher standard. In another letter to Löwenthal later that August, Horkheimer passed his most balanced judgment on the book, describing it as “an almost satisfactory introduction to some of our ways of thinking.”15 In the summer of 1945, Adorno wrote the draft of a letter to Karl Mannheim on the ISR’s recent and ongoing publications, something after Pollock requested after Mannheim reached out to him to inquire:

First, a little book “Society and Reason” which is now in the last stage of editing. This is based on five lectures H[orkheimer] gave at Columbia University 1944 with a number of other studies, particularly a detailed critique of both logical positivism and Neo-Thomism added. This book which should have perhaps 150 to 200 pages in print may well be regarded as a kind of “Prolegomena” to our philosophy. It is a more popular formulation of some of the leading ideas contained in the German Philosophische Fragmente which H[orkheimer] wrote together with Adorno. It is not too difficult, but should give a clear idea of our specific approach. The whole thing is built around the difference and relationship of “subjective” and “objective” reason. It uses these concepts in order to provide an introduction into the problem of dialectics of enlightenment.16

This was the task assigned to Eclipse. The ‘little book’ was to be a ‘Prolegomena’ to the basic problematic of the Dialectic of Enlightenment: “Myth is already enlightenment, and enlightenment reverts to mythology.”17 Already, this reverses the received wisdom in the reception of ‘the Frankfurt School’ that considers Eclipse “as a postscript to the work now seen as the magnum opus of the Frankfurt School's American exile: Dialectic of Enlightenment,” or even as “Horkheimer’s Dialectic of Enlightenment.”18 In the ‘Preface’ to the Dialectic, Adorno and Horkheimer explain that the task of the book is to investigate the “aporia” of “the self-destruction of enlightenment” through essayistic fragments designed for a dual purpose: (1) to show how the enlightenment, as both philosophical movement and the tendencies of modern society it expresses (“not merely […] rational consciousness but equally to the form it takes in reality”), “already contains the germ of [its own] regression”; (2) to comprehend the self-destruction of the enlightenment by means its uncompromising self-critique—the reflexive appropriation of its “regressive moment” through reflection, as well as excoriation of the prevailing tendency in enlightenment thus far to “leav[e] consideration of the destructive side of progress to its enemies.”19 Using Adorno’s draft for Pollock, we can distinguish between the task of the Dialectic and the task of Eclipse as its ‘prolegomena.’ According to Adorno, Eclipse

Should be ‘a more popular formulation of some of the leading ideas contained in the German Philosophische Fragmente’ for an Anglo-American audience;

Should not be ‘too difficult,’ but ‘should give a clear idea of our specific approach’;

Should, through the dialectical construction of its core antithesis (‘difference and [inter-]relationship’) of objective and subjective reason, ‘use[] these concepts in order to provide an introduction into the problem of dialectics of enlightenment.’

Based on Adorno’s description here, Eclipse, like Kant’s own Prolegomena (1783), seems to be written not to “be serviceable for the systematic exposition of a ready-made science, but merely for the discovery of the science itself.”20 In making recommendations for the ‘Preface,’ Horkheimer writes Löwenthal, 12/28/1945: “It should be mentioned that the ideas in this book are derived from the more comprehensive and precise philosophical theories as they are contained in the FRAGMENTE, published by the Institute.”21 In a letter to Pollock, 12/18/1945, Horkheimer describes Eclipse as the “exoteric version of thoughts already formulated” in the Fragmente, and laments that his work on the manuscript for Eclipse (“these last weeks, during which I made myself an expert in American pragmatism…”) had prevented him from resuming his collaboration with Adorno on the Rettung, their long-planned, unwritten sequel to the Fragmente/Dialectic (“the development of a positive dialectical doctrine which has not yet been written…”).22

Yet, in a letter to Löwenthal dated 8/19/1946, Horkheimer writes “it is our duty to have our book [viz., Eclipse and Dialectic] published as soon as possible” and critiques the style of Jean-Paul Sartre’s L'Être et le néant (1943) precisely because it is “a kind of simplification” of thought with the power to “make people believe that here is the cupboard which holds the truth,” a condescension of the expert to a non-specialist audience which “gives a kind of authority to the poor and desolate vulgarities which will undoubtedly be presented as the exoteric summaries of the real treasure.”23 In fact, nearly every critique the co-editors of the S&R manuscript make of suggested additions and revisions, both those proposed by others and their own contributions, emphasizes the same danger in the concision and accessibility of the text: it threatens to give the impression of a false depth, an esoteric doctrine of which it is the vulgarization. Horkheimer and Adorno are particularly worried about this, as Eclipse was supposed to be something like an English-language précis of the Fragmente.

In a letter to Löwenthal dated 6/3/1945, both of Adorno’s ‘critical theses’ on the first revised manuscript begin from the comparison of the method of presentation in Eclipse with that of Hegel’s Phenomenology.24 (Horkheimer even calls Eclipse “my Hegel.”)25 Like Hegel does in his “Preface” to the Phenomenology,26 Horkheimer—along with Adorno, whose lengthy additions and inserts to Eclipse are largely devoted to addressing this issue—actively courts the paradox of making “science,” which “seems to be the esoteric possession of only a few individuals,” into something “exoteric, comprehensible, and capable of being learned and possessed by everybody” by constructing a path for “unscientific consciousness […] to enter into science,”27 as the reader “has the right to demand that science provide him at least with the ladder to reach this standpoint.”28 Eclipse, like the Phenomenology, should be the “coming-to-be of science itself” and “beget the element of science” that the un-initiated reader “must laboriously travel down a long path” to gain for themselves.29 The science Eclipse-as-prolegomena should initiate the reader into must accordingly incorporate the possibility of the reader’s initiation into the science and the obstacles which might block the reader from doing so into the science itself.30 This comes with significant risk for both of the parties involved—the ‘non-scientific’ reader must be willing to hazard their preconceptions and follow the development of the ‘element of science,’ while the ‘scientific’ author must find a way to recover the ‘scientific’ standpoint by abandoning it in the assumption of the standpoint of the ‘non-scientific’ reader as their point of departure. The method of presentation for this initiation can only be given theoretical justification from the perspective of the science it might very well fail to initiate the reader into; the ‘scientific’ author fails to the same extent they artificially restrict themselves to a stock of formal methodological procedures and ready-made examples which, from the author’s perspective within the science, must result in the discovery of the science itself as a matter of mechanical necessity.31

There is no royal road to science—not for Hegel, who concludes his “Preface” to the Phenomenology with a critique of the idea that a “Preface” could provide the readers with an external survey of the essentials of the science from above,32 nor for Marx, who prefaces the French publication of Capital by “forewarning and forearming” his readers, steeling them for the “fatiguing climb” of the “steep paths” of science against becoming “disheartened because they will be unable to move on at once” to the conclusion or at least to “the connexion between general principles and the immediate questions that have aroused their passions.”33 As with the Phenomenology, Eclipse is meant to be a “path of despair,”34 and the despair of its editors in the agonizing preparations for the manuscript reflects this acutely. If the method of presentation for both the Phenomenology and Eclipse requires that “the educator must himself be educated,”35 this applies even more so to Eclipse and the Fragmente, since, as Horkheimer distinguishes their thinking from Hegel’s in conversation with Adorno in 1946 about the long-planned sequel to the Dialectic, or the Rettung (‘Rescue’): “Hegel had absolute reason, fulfillment, as his guide (Leitfaden). What do we have as a guide?”36 Adorno’s proposed ‘solution’ to both the problems he raises on the method of presentation in Eclipse is to consciously and clearly incorporate them into the conclusion of Eclipse itself: “Speaking crudely, the last chapter must explicitly answer the questions which have been raised by the first, and it would by making their unanswerability truly clear.”37 From Horkheimer’s first attempts at composition of the lectures for Society and Reason in late 1943 through the last of Adorno’s in-depth modifications and insertions to the manuscript for Eclipse in January 1946, the text would be held to this theoretical criterion.

§3. Early Reception of Eclipse.

Despite, or perhaps because, of their painstaking efforts, the earliest readers of Eclipse in the ISR’s intellectual circles would struggle with this ‘unanswerability’ more than anything else in the book. The fear Adorno and Horkheimer repeatedly expressed in their letters through late January, 194638—namely, that the book would seem like a defense of ‘objective’ reason in static opposition to ‘subjective’ reason,39 rather than the ‘mutual critique’ of each concept of reason through its immanent reversal into the other—came true. (Eclipse is still largely read this way, an interpretation which derives its pedigree from Jürgen Habermas, among others.)40 In 1949, Ruth Nanda Anshen (1900-2003)—an American philosopher and publisher who was Horkheimer’s friend, and sometimes-publisher, from his time in NYC— published a double review of Horkheimer’s Eclipse and Erich Fromm’s Man For Himself (1947) through the Philosophical Review, in which she proposed an ‘analogy’ between her own Neo-Thomist philosophy, Fromm’s humanism, and Eclipse. Horkheimer was furious. He drafted a letter to the editorial board which, though he never sent, contains a concise refutation of the apparent defense of ‘objective reason’ in Eclipse:

[Dr. Anshen’s] article is filled with stereotyped attacks against dialectical philosophies of various shades. She leans heavily on pseudo-religious prestige values and she boldly proclaims her belief in some of the most commonplace, universally accepted ideals. My intentions are precisely the opposite. In spite of my critiques of “subjective reason” and its relapse into a second mythology—a critique bearing only a superficial resemblance to certain antipathies nourished by Dr. Anshen—I have never advocated a return to an even more mythological “objective reason” borrowed from history. Decisive elements of my own philosophy were derived from idealistic as well as materialistic schools of thought, and I have attacked enlightenment in the spirit of enlightenment, not of obscurantism. Much of my argument is devoted to the rejection of such “panaceas” as streamlined Thomism. Philosophically or, rather, pragmatically ordained religion, stripped of whatever substance it may once have derived from genuine tradition, has by now tilted over into untruth; it can be swallowed only with a bad conscience. Consequently, it becomes vindictive and repressive, fitting perfectly with sinister political purposes: the justification of irrational hierarchies everywhere. To make the slightest concession to this brand of perennial wisdom involves a betrayal of the millions who were murdered in the name of the authoritarian state which also called itself a “new order.”41

Of the earliest readers, Herbert Marcuse might be the most perceptive and insightful. In a letter to Horkheimer dated 7/18/1947, Marcuse identifies that ‘unanswerability’ Adorno hoped to foreground as the conclusion of the dialectical movement—through which, to adapt the chiasmus in the ‘Preface’ of the Dialectic, objective reason is already subjective, and subjective reason reverts to objective—at the core of Eclipse:

I have read your book. For now, I will just say: I agree completely. If only you would have a chance to develop all of the lines of thought you were only able to hint at here in the near future. Particularly the one which worries me most: that the reason which reverses into consummate manipulation and domination remains reason all the same; that the real horror of the system lies within rationality [Vernünftigkeit] rather than anti-reason [Widervernunft]. This, of course, has been said—but you must still provide the development for your reader—no one else can, or does. I would like to speak with you about this at much greater length. The German situation is already at an even more advanced stage than the development you analyzed: negative rationality becomes positive insanity.42

Despite being cited as a critique of Horkheimer’s (as well as Adorno’s) theoretical perspective at the time of Eclipse and the Dialectic,43 Marcuse’s letter is an expression of exactly that unity of opposites its author(s) hoped to find in their readers: a deep disquiet over the fate of reason it reconstructs and anticipates rivaled only by the force of the resolve to complete the thought that thinks it.

§4. A Voice in the Desert.

Thinking, the endeavor of an individual to discover by himself the ultimate truth and teach it, is discredited. Look around — is there a place for such a man?

—National Socialism and Philosophy. [Lecture I. Problem: Authority of the Epoch]

Out of all the early reviews, however, my favorite is Löwenthal’s, which he sends in a letter of 1/16/1946. This letter was one of many Löwenthal wrote trying to remind Horkheimer how incredible it was that a book like Eclipse, for all its flaws, was being published at all:

Above all I wish to express my admiration for the additional text. I have the definite feeling that now you have achieved a document which, for the first time in [the] English language, can give an adequate idea about the impression of one philosopher’s voice in the desert of streamlined society today. Since I believe in the presence of unknown spiritual friends even on this continent, I look forward to the time where people will contradict the smooth critics who see in Ernst Cassirer the non plus ultra of philosophical thinking in this epoch.44

As James Schmidt (2007) notes, the pointed aside about Ernst Cassirer (1874-1945) was prompted by the unexpected, posthumous success of Cassirer’s Essay on Man (1944) and Myth of the State (1946) among “educated readers” in the American public.45 The incompatibility between Cassirer’s distinct brand of neo-Kantianism and critical theory is less relevant for explaining the reference than the disparity between Cassirer’s reception in the American university system and the ISR’s. After settling in the United States in 1941, Cassirer taught at Yale until 1944 and, from 1944 through his sudden death in the spring of 1945, at Columbia University.46 In the course of a single year, Cassirer had a much more enthusiastic reception in and much greater impact upon the intellectual culture of Columbia and affiliated institutions than the ISR ever had or ever would. The ISR’s problems with Columbia started in the late 1930s when their financial situation significantly worsened. This set the stage for a series of events ultimately leading to the ISR’s official disaffiliation with Columbia in Summer 1946.47 In 1941/42, the ISR would be forced to effectively dissolve in all but name after the group failed to secure funding for any of the many ambitious, multidisciplinary project proposals they began drafting, revising, and submitting in fall 1938. Columbia’s sociology department had been instrumental in bringing the ISR to the US in 1934. Because the ISR’s financial crisis coincided with the outbreak of WWII, they began to apply for more courses, and even teaching appointments, at the same time the odds that Columbia would ever employ most members of the ISR full time reached new lows. The sociology department continued to turn down their proposed lecture courses through 1942.

Beyond financial constraints however, the sociology department was skeptical of the ISR’s ‘theoretical’ approach to social research and troubled by their lack of respectable social-scientific publications. Schmidt even suggests that the first impetus Horkheimer felt to revise the S&R lectures for publication was based on a comment made by Robert Lynd of the sociology department, which Löwenthal paraphrases in a letter of 9/25/1944 to the effect of: “University authorities feel that we have not ‘come through in a big way’ in the same sense as in Germany.”48 By the time Eclipse was published in 1947, however, it was too late for the book to have any impact on their relationship with Columbia. In a letter to Horkheimer dated 7/19/1947, the sociologist Paul Lazarsfeld (1901-1976), a fellow exile who, despite seemingly irreconcilable theoretical differences, had worked closely with the ISR on a variety of projects since the mid-1930s and was their primary contact with Columbia’s sociology department, where he’d been fully employed since 1940, writes approvingly of Eclipse:

I might add at this point that I also feel that your Eclipse of Reason is a real step forward toward the kind of institute’s policy I have always hoped you would follow. The book is written in such a way as to make it understandable to many people and will undoubtedly also influence many readers. As a matter of fact, I, myself, have never so clearly understood before some of your basic ideas. In a way, then, the last few years have brought about an intellectual situation which should make the role of the institute in this country a much more effective one, but that raises a question on which I would like very much to get some information from you. The first ten years the Institute was a concrete administrative unit but it spoke a language and had a policy which, in my opinion, defeated many of its purposes. Now, on the intellectual side, very great progress has been made, but at the moment, the Institute is no clear-cut administrative body. This again seems to me a real danger. Obviously, the effect of the new publications would be much greater if they were to emanate from a clearly defined administrative center. What plans have you in this respect? I would think that any affiliation, even with a small university, would be very desirable. I realize that would require considerable personal sacrifices for many of you, but the advantages would be very great.49

Here, Lazarsfeld is referring more or less directly to the offer he first made to Horkheimer in the summer of 1946 to integrate the ISR into the Columbia sociology department’s Bureau of Applied Social Research. He served as its first director after its founding in 1944.50 This was not a sacrifice the few remaining members of the ISR were willing to make. As Horkheimer writes Löwenthal just before Lazarsfeld would make the long-anticipated offer official: “One of our main tasks, the critique of culture, includes the critique of conceptions which underly the division of labor in the sciences and […] academic training. This demands as much independence as possible, theoretically and practically.”51 By 1943, the odds of Horkheimer securing a longer-term teaching position in Columbia’s philosophy department were virtually non-existent.52 In the summer after Horkheimer proposed the S&R series and was contracted to teach it the following spring, several members of the philosophy department publicly expressed doubts about the ISR (which they considered poorly managed and responsible for its own financial troubles), and the ISR core’s anxieties about the department’s hostility towards them were seemingly confirmed in two early reviews of Eclipse by Columbia philosophers—Glenn Negley (1947) and John R. Everett (in 1948)—who “appeared to be settling old scores.”53 In addition to misgivings about the ISR’s distinctively ‘theoretical’ approach to sociology and ‘European’ approach to philosophy, however, there was the fact that since 1940 the ISR had been suspected by both university officials and law enforcement of harboring Marxist and even communist sympathies.

Despite the fact that “[i]t was hardly ever possible to nail down suspicions of Marxism as a reason for difficulties that were being made for the Institute,” whatever“[m]inor successes” they had in momentarily allaying suspicion “were frustrated by the fact that Horkheimer's Institute was becoming […] more left-wing,” and explicitly so in a number of its publications, around 1940.54 In June 1943, someone who was previously suspicious of the ISR—whether at Columbia or another university in their NY academic orbit—apparently began to prepare to make a formal accusation. Pollock immediately notifies Horkheimer, and the charges were apparently serious enough for Horkheimer to draft a long response to Columbia university defending the scientific integrity of the ISR against the claims that they were a front for advancing a radical political agenda.55 In one sense, the accusation was baseless. Most members of the ISR observed a ban on overt political activities during their time in the US.56 In another sense, the accusations could have led to something much more serious if the ISR hadn’t been as careful as they were, even if some of their attempts “to avoid even the appearance of radicalism border on the comic,” like using ‘dog-ate-my-homework’ tactics to explain why certain (explicitly communist) essays were missing from a limited print of the ISR’s memorial volume for Walter Benjamin (Zum Gedächtnis [1942]).57 Like their other works through the 1940s, Eclipse was subjected to the ISR’s typical process of ‘tactical’ self-censorship. Notably, this resulted in the removal of Horkheimer’s ‘disclaimer’ to S&R which opened the series, in which Horkheimer identified the crisis of reason with the crisis of European socialism (see the ‘Editor’s Note’ to §VI, below). It also resulted in the elimination of Horkheimer’s profession of “dialectical materialism” in the course of his polemic against Neo-Positivism and Neo-Thomism in “The Revival of Dogmatism” (see §V, below) as the essay was repurposed for Chapter 2 of Eclipse, “Conflicting Panaceas.” Nevertheless, Horkheimer hoped that Eclipse would be enough of a success that it could give them the opportunity to publish more explicitly ‘materialistic thought’ in English.58 Horkheimer wasn’t always so guarded at Columbia either. In a series of lectures titled National Socialism and Philosophy delivered in the spring of 1945 through the sociology department (§VIII, below), Horkheimer reformulates the question of the role of philosophy in postwar European reconstruction by posing the problem of the relationship between scientific and utopian socialism anew in the world ‘after’ Nazism.

Löwenthal’s admiring comment on Eclipse is a ‘spiritual portrait’ of Max Horkheimer, circa 1944-1946: the philosopher as a voice in the desert of streamlined society, awaiting the time when people will contradict its smooth critics, seeking his unknown spiritual friends across a continent of the indifferent and suspicious. The portrait is generous because it presents Horkheimer in the integrity of his boundaries, but also testifies to his dogged resolve—keeping the afterimage of socialist enlightenment in the totality of its eclipse so it would not be forgotten before the light that might still break:

I am well aware that there are strong counter-tendencies at work to combat nihilism. However, I must admit that I do not feel justified in predicting that these destructive processes will be purged in the near future. Nevertheless, that there are forces in the making to assure that this purging will not be indefinitely postponed seems beyond dispute. One of these consists in the increasing awareness that the unbearable pressure which is today brought upon the individual is not derived from inescapable necessity. More and more men are coming to see that it does not even spring directly from the purely technical requirements of production, but from the social structure. To state it more precisely: Indeed, the recent intensifications of repression are themselves testimony to the fact that a better world is in its birth throes. All the forces which are opposed to this world are trying desperately to forestall its arrival. The very processes which have led to the destruction of old mythologies and ideologies, to which even the best available versions of individuality belong, threaten to issue in a new era which cannot yet be described by philosophy, even by a much better one than mine. The terror of fascism is maintained not only because fascism can cope more easily with social atoms that with conscious human beings, but because it was feared that ever-increasing disillusionment with all ideologies might leave men free to realize their own and society’s deepest potentialities. Indeed, in some cases, social pressure and political terror have tempered the profoundly human resistance to irrationality which has always been the core of true individuality. The real individuals of our time are not the inflated personalities of popular culture, the conventional dignitaries—the real individuals are the martyrs who go through infernos of suffering and degradation in their resistance to the “iron heel” of conquest and oppression. These unsung heroes sacrifice not only their lives but freely submit their personalities to the terroristic annihilation which others undergo unconsciously through the social process. The anonymous victims of the concentration camp and the dungeon are the symbols of the humanity that is striving to be born. It is our task to translate what they are doing into language which can be understood even when their voices have long been silenced by tyranny.

—Society and Reason, Lecture IV.

I. Possible Topics (Jan.-Feb. 1943).

[…] I thank you for your thoughtfulness with regard to the lecture on “American and German Philosophy.” You were right in saying that this lecture will perhaps cause me a little more work than the others. I think, however, that it adds considerably to the attractiveness of the whole list. If the Faculty should pick out this series, I would probably take advantage of the occasion and publish something on American philosophy that might well prove helpful to our practical plans. But, you know, that I am very doubtful about the whole matter anyhow. […]

—Horkheimer to Leo Löwenthal, 2/2/1943.59

Editorial Note. After seeking advice from Leo Löwenthal and Paul Tillich, who’d proposed on Horkheimer’s behalf that he return to teach a lecture series to Columbia, Horkheimer cut: “C. Theories on Philosophy and Society,” the most explicitly Marxian, and “F. Basic Concepts of Social Philosophy,” which roughly followed the pattern he’d previously set out (in approx. 1938) for a ‘dialectical logic’ that was to begin with a critique of dominant sociological categories.60 As James Schmidt (2007) explains, Löwenthal’s advice that Horkheimer focus on “A. Society and Reason” is indicative of the keen sense Löwenthal had for the direction of Horkheimer’s ongoing collaboration with Adorno.61 Having been cut down to four alternatives, the final proposal Tillich forwarded to the Columbia Department of Philosophy in late February, 1943, listed the following: “A. Society and Reason,” “B. Philosophy and the Division of Labor,” “C. Philosophy and Politics,” and “D. American and German Philosophy.”62 In the letter of hire dated 3/5/1943, Herbert W. Schneider, Executive Officer of the Columbia Department of Philosophy, would confirm Horkheimer’s temporary appointment as a visiting lecturer for “public addresses on social philosophy” for the Spring Session of 1944 and requests on behalf of the department that Horkheimer teach “A. Society and Reason” while incorporating as much of “D. American and German Philosophy” as feasible.63 While Horkheimer does not have a chance to develop an explicitly comparative approach to the histories of American and German philosophy in S&R or even Eclipse, they constitute Horkheimer’s single most sustained engagement with the traditions of American social theory from a perspective as critical of the German philosophical canon as shaped by it.

A. Society and Reason.

Reason as the basic theoretical concept of Western civilization.

Civilization as an attempt to control human and extra-human nature.

The rebellion of oppressed nature and its philosophical manifestations.

The rise and decline of the individual.

The present crisis of reason.

B. Philosophy and Division of Labor.

The bearing of social structures upon philosophical thinking.

How industrialization tends to transshape [sic] philosophy into an “exact science”.

Psychology as an example for the transformation of philosophical thinking into a science.

Sociology as an example for the transformation of philosophical thinking into a science.

Philosophical attempts to overcome scientific specialization.

C. Theories on Philosophy and Society.

The role of the philosopher in ancient and modern society.

Philosophical utopias (Morus, Campanella, Bacon).

Political theories of enlightenment and romanticism.

The Marxian doctrine of ideology.

Modern sociology of knowledge (Wissensoziologie).

D. Philosophy and Politics.

The dissolution of Feudal Society and the rise of modern philosophy.

Absolutism and Reason.

French Enlightenment as a political movement.

Philosophies of counterrevolution.

The Philosophy of modern democracy.

E. American and German Philosophy.

The different role of philosophy in both countries.

The concept of History in Western and German Philosophy.

The concepts of Western civilization and German “Kultur.”

The expression of American democracy and German traditionalism in divergent philosophical theories.

The function of philosophy in world reconstruction.

F. Basic Concepts of Social Philosophy.

Society and the individual.

Progression and retrogression.

Freedom and necessity.

Ideas and ideologies.

The idea of justice.

II. Notes for Lectures I-III (Late 1943).

Lecture I.

What is philosophy? In a certain sense, philosophy is not a science and in a certain sense it is all science. Science cannot simply be assumed to be the truth, but is first and foremost a branch of division of labor, the relationship of which to the truth is problematic.

What is reason? Difference between immediate life and reflection. Reason may have originated Darwinistically, but then it took on a life of its own. Dogs scratching at the door. Conversion from quantity to quality. Difference between humans and animals.

Are reason and philosophy identical? Different meanings of the concept of reason. The English word “reason” means understanding and reason in German. Hegel's philosophy as an explication of difference and unity. [Handwritten insert: Every concept is more than its definition: The words.]

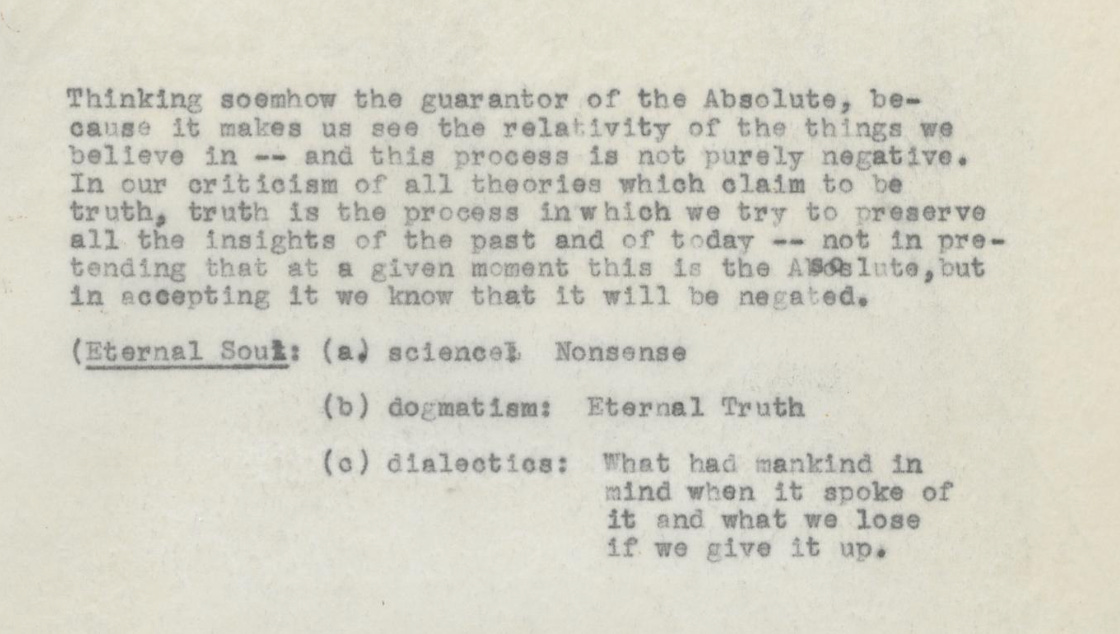

Society and reason. Can mean either: the prejudice-free society (subjective reason, self-preservation, reason as the opposite of prejudice, superstition) or objective reason = meaning, significance, the society that realizes reason, i.e. giving all things their due, not just arranging all things according to human purposes, not just controlling nature. Relationship between religion and reason. The entire history of the Enlightenment, indeed of Western civilization, is the attempt to fulfill the achievement of religion through reason.

Greek culture (definition of reason in Plato), medieval philosophy, enlightenment, Hegel.

[Handwritten marginal insert:] Western civilization came to formalize the concept of reason because it took the content [X] for granted. Its goal: self-preservation, mechanized civilization. Therefore, in instrumentalism, religion would become irrationalizing. —That precipitation of millennia-old experience means of perception. Example of the movement of the concept of peace as the "truth" of history as an element of their concepts. Differentiation from positivism and irrationalism. German and western concept of history and reason.

Lecture II.

The domination of nature in human society is implemented as class domination. It is impossible to say which comes first. Self-preservation rebounds on the self.

The boundary to radical control was originally set heteronomously by concepts such as love, justice, etc. These concepts proved untenable before the Enlightenment, and residues of the process of domination remained abstract selves and mere material.

Demythologization and positivism.

Our society as a monopoly society is the necessary result of the destruction of the myth.

Lecture III.

If the problem of the rebellion of oppressed nature is treated psychologically, as is done in monopoly society, the rebellion becomes a neurosis. Examples from “Civilization and Its Discontents” (Freud).

Romantic philosophy. The genuinely romantic philosophies, which assert the violated nature through the concept (Schelling, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche) and the deceitful modern ones, which evade the concept in favor of conceptless life and thus commit themselves to domination (Spengler, Klages, Revivals).65

[Handwritten Notes.]

Differentiation between positivism as an epistemological doctrine and as a public-intellectual attitude. Relation between the two.

Rationalism departs from empiricism because the objectivity of rational insight, the view of the real individual, is at risk. [X] Religion and empiricism emerge in the idea that insight is impossible; the one speaks of reason, [...] absoluteness [X] the dominating of life.

But there is no way that it would be possible for it to be conceived.

Developing comparison: pragmatism and its ambivalent relation to democratization. Structure: majority religion. Majority-pure work contradicts ideals.

III. Letter: “On problems of Scientific Style” (Nov. 1943).

Note: On Style. Written in response to two documents from Pollock titled “memoranda 21 and 22,” which contained proposals for formulating and experimentally testing hypotheses for ‘the practical defense against anti-Semitism’ in the United States. This excerpt was excerpted by either Pollock or Horkheimer himself, typed up in an independent 3-page manuscript, and filed alongside the S&R lectures in MHA Na [653].66 Horkheimer prefaces the following excerpt as follows:

I shall give you here the thoughts as they occurred to me while reading your notes. I won’t organize them at all; ideas which might be worthwhile considering may be preceded or followed by most superficial objections. It is the nature of critical remarks that they don’t show the points of assent. Therefore, I state that although maintaining my general question mark with regard to the wisdom of such a comprehensive presentation right now, I think your idea, how to organize it, is certainly useful.

After the excerpt below, Horkheimer returns to Pollock’s proposed program and gives line-by-line suggestions for revision. As Horkheimer indicates in the letter, the complex of problems with ‘scientific style’ includes:

The language barrier. Horkheimer was forced to confront this barrier repeatedly in his renewed efforts to become more fluent in English before his lecture series began. In January 1943, Horkheimer writes “[m]y own philosophical cogitating has terminated” given the efforts of “trying to accomplish the miracle of conquering the world’s most difficult language,” explaining that the goal of his lessons is to “kindle the fire of English thinking in me.”67 By January 1944, however, a month before the S&R lecture series is slated to begin, he writes to Pollock, expressing his despair over the discrepancy between his German writings and the lecture manuscripts dictated in English:

Ceterum censeo: it is a great pity, it is almost a catastrophe that I have to interrupt my work in order to deliver lectures in a language which I do not master. I am quite aware that it is I who insisted on getting this appointment. I did it because of the well known motives. Now I must bear the consequences. However, I want to state that the four months, one third of a year, which I sacrifice for this purpose, are a terrible investment. I could have devoted them to our philosophical work, which is now in a decisive state. Never in my life did I feel so deeply the victory of external life over our real duties. If I could only believe that the lectures in themselves were really worthwhile. But reading a page of these lectures as I now start to dictate them, and comparing it with a page of my own texts, I must say it is almost a crime. The world is winning, even in our own existence. This makes me almost desperate. Never mind, I shall be gai et courageux, and it will work out all right, because we are doing all we can.68

The divergence between American and German ‘scientific traditions.’ Horkheimer’s acute awareness of the problems this presented in communicating the ISR’s conception of social theory to American audiences is evident from his introductory lecture to the ISR’s 1936/37 Columbia seminar on “Authority and Society”—featuring lectures by Herbert Marcuse, Paul Lazarsfeld, Friedrich Pollock, Julian Gumperz, Erich Fromm, Franz L. Neumann, and Leo Löwenthal. This introduction is an extraordinary document. Opening with an apparent disclaimer about the difference between German and American scientific thought, Horkheimer presents this difference within the context of the shared horizon. The cliches about ‘metaphysical’ Germans and ‘rational-empirical’ French and Anglo-American traditions are grounded and relativized within the historical development of modern society—that is: capitalist society, and trans-Atlantic ‘bourgeois’ culture—in which the popular image and self-conceptions of scientific thinkers have converged and diverged since the enlightenment. Rather than moving on from his disclaimer, Horkheimer introduces the central categories of the lecture series as a whole, Authority and Society, through giving fuller articulation to the disclaimer itself. The introductory lecture ends with the argument that social-theoretical investigation of the problem of authority in contemporary society requires reflection on the social theorist as an authority in the society they investigate, something which is just as lost in the inward-facing ‘metaphysical’ approach of the Germans as it is in the outward-facing ‘rational-empirical’ approach of the French, English, and Americans.

The qualitative transformation of language in history. This last problem is in a certain sense the most difficult, as it encompasses the other two. It becomes all the more pressing the more progress Horkheimer makes in overcoming the language barrier and adapting his writing style to the standards of the American scientific tradition. The progress he’s made in both by late 1943 is manifest in the hybrid structure of the letter from which the excerpt is excerpted itself. The last three pages show Horkheimer applying ‘the standards of the American scientific tradition’ exhaustively to the syntax and semantics of Pollock’s memo; the first two pages, the excerpt itself, are a testament to Horkheimer’s progress in overcoming the language barrier which once ‘terminated’ his ‘philosophical cogitation.’ “On problems of scientific style” is as much a fragment of totality in absentia as many of the ‘Notes and Sketches’ Horkheimer had already written in German for and with Adorno. In addition to the mutual exclusivity of overcoming the language barrier (aphoristic form) and adapting to scientific convention (memoranda) the hybrid structure of the letter implies, Horkheimer experiences a kind of temporal displacement: having become more proficient in English, Horkheimer can now feel anachronistic in two languages instead of just one. One war, two fronts. It confirms the intuition Horkheimer once described in a letter to Löwenthal, dated 7/21/1940, when recounting what it was like to hear a speech of Hitler’s broadcast over car stereo as he drove across the American countryside between Kansas and Colorado:

I heard Hitler’s speech on the way here. His word reaches beyond the world’s plains and oceans; it penetrates the most distant mountain valleys. But I have never felt so strongly that it is not exactly a word but a force of nature. The word has to do with truth, but this is a means of war and is part of the gleaming armor of the inhabitants of Mars. But the determination of what is truth is our actual task. […] We have to rewrite our logic.69

“On problems of scientific style” is a hybrid of hybrids. In it, Horkheimer returns to the problem of integrating his more ‘academic’ mode of authorship and his more ‘literary’ one, a difficulty he’d consciously internalized in his German compositions since the mid-1920s, through the medium of the English language. In terms of the three distinct but interconnected problems we’ve developed above, Horkheimer’s letter opens with a reflection on the problem of the split between scientific and non-scientific style (2), amplified by a sense of estrangement from English Horkheimer shares with Pollock when writing in English (1), prompting a more synoptic reflection on the diremptions which arise in the historical transformation of ‘the linguistic medium’ itself (3).

The conclusion of the excerpt is rather bleak. With the loss of naive metaphysical belief in a transcendent signified, the seriousness of the signifier—or semblance (Schein)—is lost as well. As language is functionalized in what Horkheimer will call the “all-comprehensive psycho-technics” at the end of his draft of LII, even one’s acceptance, whether earnest and accommodating (“in order to believe them honestly once and for all…”) or ironic and critical (“… or to refute them as lies”), of the ‘surface value,’ or significance, of words under the conditions of the present would only prove that they fail to understand the transformations of the linguistic medium itself. This raises a final question—that of the standpoint of the critic himself. In other words, how is it possible for Horkheimer to write this letter in the first place if he’s right about the impossibility of either expressing truth (“the determination of what is truth is our actual task”) or even refuting lies in language with language anymore? Like so many of the seemingly ‘pessimistic’ texts authored by Adorno and Horkheimer throughout the early 1940s—including the Dialectic of Enlightenment itself—, “On problems of scientific style” performs a protest against ‘what exists’ precisely through articulating the impossibility of protest. As Horkheimer writes to Adorno in critical remarks on the latter’s draft of The Philosophy of New Music (not published until 1949) in a letter dated 8/21/1941:

The language we have to create for ourselves should be neither communicative nor exactly adapted to the content. […] Sade’s teaching is, in a unique way, the antithesis of the compulsion of what exists. Your essay proves that this is also precisely true of music. In the future I see our task as no longer being satisfied with critically demonstrating this function in cultural phenomena but taking it on ourselves. I see in your essay not merely a prolegomena to doing so, as you originally wanted, but already as the transition to doing so.70

And in a letter to Marcuse dated 12/19/1942, Horkheimer explains the ‘negativistic’ tone of his drafts for Ch. 1 of the ‘Dialectic’ as the performance of the positive function of critical reason:

During the last few weeks I have devoted every minute to those pages on mythology and enlightenment which will probably be concluded this week. I am afraid it is the most difficult text I ever wrote. Apart from that it sounds somewhat negativistic and I am now trying to overcome this. We should not appear as those who just deplore the effects of pragmatism. I am reluctant, however, to simply add a more positive paragraph with the melody: “But after all rationalism and pragmatism are not so bad.” The intransigent analysis as accomplished in the first chapter seems in itself to be a better assertion of the positive function of rational intelligence than anything one could say in order to play down the attack on traditional logics and the philosophies which are connected to it.71

Likewise, in a letter to Marcuse dated 10/11/1943 in response to the latter’s concern that Horkheimer’s essay on “The Sociology of Class Relations” [1842/43] advocated a kind of social pessimism, Horkheimer responds:

I have not the slightest inclination to advocate an attitude of social pessimism. On the other hand, however, you will agree with me that theory is critical. That means, among other things, that it concentrates on those social and political conditions which have to be overcome. The confidence that the possibility of such overcoming exists is a presupposition, so to speak, an a priori of theory as a whole as well as of each particular sentence.72

Though unspoken in “On problems of scientific style,” this is precisely the gesture Horkheimer will make at the conclusion of his draft of LII (§IV, below), “Revival” (§V, below), and LV of S&R itself (§VI, below). In his 1946 public lecture titled “Reason Against Itself,” which is meant to be a précis of both Eclipse and the Dialectic, Horkheimer gives what is perhaps his most explicit formulation of this task:

As far as, our situation today is concerned, there seems to be a kind of mortgage on any thinking, a self-imposed obligation to arrive at a cheerful conclusion. The compulsive effort to meet this obligation is one of the reasons why a positive conclusion is impossible. To free Reason from the fear of being called nihilistic might be one of the steps in its recovery. This secret fear might be at the bottom of Voltaire's inability to recognize the antagonism between the two concepts of philosophy, an inability contrary to the idea of Enlightenment itself. One might define the self-destructive tendency of Reason in its own conceptual realm as the positivistic dissolution of metaphysical concepts up to the concept of Reason itself. The philosophical task then is to insist on carrying the intellectual effort up to the full realization of the contradictions, resulting from this dissolution, between the various branches of culture and between culture and social reality, rather than to attempt to patch up the cracks in the edifice of our civilization by any falsely optimistic or harmonistic doctrine. Far from engaging in romanticism, as have so many eminent critics of Enlightenment, we should encourage Enlightenment to move forward even in the face of its most paradoxical consequences. Otherwise the intellectual decay of society’s most cherished ideals will take place confusedly in the undercurrents of the public mind. The course of history will be hazily experienced as inescapable fate. This experience will provide a new and dangerous myth to lurk behind the external assurances of official ideology. The hope of Reason lies in the emancipation from its own fear of despair.73

“On problems of scientific style” is a stylistic experiment in its own right, one through which Horkheimer seeks this kind of hope for himself in giving fuller expression to his despair at the prospect of mastering the English language through the medium of English prose itself.

On problems of scientific style.

[Excerpt from: Horkheimer to Pollock, 11/28/1943.]74

… When I am reading documents like the one in question, whether they emanate from us or from other sources, I become well aware why I am unable to do anything useful in that realm. I am simply at a loss to understand what people who have even superficially studied the problem can learn from such papers.

Since I cannot get rid of the impression that in addition to the usual dullness and naivety of such documents, our presentations express a certain perplexity due to our inability to master the English style of thinking and writing, I strongly advise to have a good American writer assist you in formulating and organizing the final edition of this text.

With regard to myself, I become more and more aware of my utter inability to do such things. This language has developed into a tool by which you can point to things you already know. It does not enter into an interaction with the object. Never is the word understood as reflecting the nature of the object, nor is the experience of the object shaped by the intellectual potentialities inherent in the particular word expressing the object. The relation of word and thing, of sentence and subject matter, is purely mechanical alone. Speech must be to the point. In our case this means that we must show in how far we have revealed new facts or organized old ones in such a way that the knowledge gained by them can be put to a new use. Wherever the tool of language and style has been adapted so well to reality, the scientific and business methods of speaking and writing are so highly developed that each empty promise to deliver new facts or new uses or to show new pragmatic possibilities is immediately noticed in how you express yourself. Once the linguistic medium has become the realm of sales talk, the ears have become most delicate instruments for discovering everything that sounds phony or empty in such talk.

One of the main reasons for the so-called crisis of our culture (but this does not belong here) is that each word which does not point to a tangible fact, good and bad ideals, true and false religions, pleas for humanity and for inhumanity, is not only interpreted but directly—i.e. by virtue of modern language—sounds like sales talk. Whoever is listening to it, rich or poor, dumb or intelligent, is well trained in scenting what kind of social or other forces are behind the sales talk, whether it represents a reliable firm, for instance an ecclesiastical organization with experience in mass guidance, diplomacy and other necessary functions, or whether it is the poor advertisement of a firm doomed to liquidation by the progress of modern economy. Even the private conversations of business men, intellectuals and other experts are understood as signs of what they are trying and able to sell, be it only their mental versatility. One cannot help thinking of those 19th century middle class daughters who were exclusively trained for catching a husband. Their modest artistical performances, their sentimentality and nostalgia were a product of planned education. But there is a difference between those days and ours. Many a young man who fell victim to the skillful achievements of his future mother-in-law awakened, too late, to reality. But despite those experiences, despite the fact being well-known to everybody, each young lover, male and female, took the phenomenon at face value and believed in it, not a few of them until the end of their lives. The appearance (der Schein)75 was taken seriously, in love as in art. That was the way how truth existed.

Industrial monopolism which has superseded the poor old, half-natural technique of buying and selling in all fields, has changed the character of language altogether. It has eliminated the last metaphysical elements. A man who would take ideological statements at their surface value, whether he would do so in order to believe them honestly once and for all, or to refute them as lies, would not be an idealist, but would simply misunderstand the meaning of the words. …

IV. Lecture II: On the Domination of Nature [First Draft] (Late 1943).

Editor’s Note: Critique of Pragmatism and Critical Marxism.

Critique of Pragmatism. Originally listed with the wordy title “Civilization as an attempt to control human and extra-human nature,” the lecture transcribed below was never delivered in this form. In a letter to Adorno dated 2/11/1944, Horkheimer explains that the change in focus was his attempt to address the objections raised by partisans of John Dewey in the discussion following LI. In response to their contention that Dewey’s ‘philosophy of experience’ already indicated a way out of the ‘impasse’ Horkheimer had developed in LI, Horkheimer abandoned his original draft and wrote a second manuscript.76 Horkheimer doubles down: approximately half of the second manuscript for LII is devoted to showing how Dewey’s own body of work—particularly the books Experience and Nature (1925), Philosophy and Civilization (1931), and Experience and Education (1938)—constitutes a case study uniquely suited to exemplifying precisely the pathology within reason itself Horkheimer diagnosed in LI, and for which Dewey’s philosophy of experience had been prescribed as a remedy:

So far, I had two lectures. The first one originated a sharp rencontre with Randall who presided. Since he felt hurt by what I said, but was unable to argue, he simply pretended that the problems were not American. The discussion was very lively and the interest of the audience very outspoken. That meant that I had to use the greater part of the second lecture for an analysis of Dewey’s philosophy, which is the credo of everybody, I think that the effect was not bad. Even Schneider, who presided (Randall stayed away), joined the discussion and tried in a feeble way to defend Dewey, whose picture is on the wall.77

Even Schmidt (2007), an atypically generous reader of Horkheimer, is critical of Horkheimer’s apparently transcendent critique of pragmatism ”in light of European philosophical traditions with which he had long been familiar,”78 going as far as accusing Horkheimer of simply repeating his critique of Bergson in the final manuscript for LII delivered on February 10th, 1944.79 Schmidt is inconsistent, however—as he observes himself, Horkheimer’s close criticism of Dewey, Sidney Hook, and Ernst Nagel for the “Revival” essay of 1943 was essential for Horkheimer’s approach to pragmatism in the lectures for S&R. (As little as Schmidt seems inclined to defend Dewey, it is hard not to sympathize with Schmidt’s evident sympathy for Benjamin Nelson, who was assigned the thankless task of preparing the manuscript of “Revival” for publication in 1944. Dissatisfied with Nelson’s performance, Horkheimer condescended that it was likely the result of Nelson’s sympathy for Sidney Hook.)80 Schmidt’s charge that Horkheimer’s approach to the critique of pragmatism in S&R and Eclipse fails to meet Horkheimer’s own criteria of immanent critique is a serious one, and one which, to my knowledge, has yet to be sufficiently answered. Unfortunately, Schmidt’s discussion of the problem breaks off precisely where a critical examination of Horkheimer’s critical engagement with pragmatism in S&R and Eclipse should begin. This would require a survey of Horkheimer’s more and less sympathetic references to Dewey throughout the book, as well as a closer look at Horkheimer’s evident sympathy for Ralph Waldo Emerson, who is mobilized for a critique of later American philosophy several times throughout the book. Emerson is even elevated in the middle of a critique of Dewey to the pantheon of Horkheimer’s favorite anti-empiricists: “What has been consistently maintained with regard to empiricism by thinkers so antagonistic in their opinions as Plato and Leibniz, De Maistre, Emerson, and Lenin, holds for [empiricism’s] modern followers.”81

Critical Marxism. If the received wisdom in the reception of early critical theory is that Adorno and Horkheimer’s more orthodox Marxist preoccupation with class domination in capitalism in the 1930s gives way in the 1940s to a generalized historical pessimism over the necessary connection between the domination of nature and civilization itself, then the first draft of LII—along with the 1942 schema, co-authored with Adorno, “On the Relation Between The Domination of Nature and Social Domination,” which the first draft of LII repeats almost verbatim—is one of the strongest pieces of evidence to the contrary. The conventional interpretation of Adorno and Horkheimer’s theoretical development in the 1940s as a ‘farewell to Marx’ is not only unsubstantiated by extant archival materials for Dialectic of Enlightenment and Eclipse of Reason but repeatedly contradicted. Even Adorno and Horkheimer’s emphasis on pre-history—as indicated here by Horkheimer’s opening thought experiment about the “group of primitive families, prior even to the crystallization of “tribes,” […] forced, by fear of wild animals, to cross a relatively deep creek with a strong current”—is indebted in part to their reception of the late ‘anthropological’ works of Marx and Engels (e.g., in: The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State [1884]). In a letter to Marcuse dated 10/14/1941, Horkheimer writes:

[O]ur intellectual ancestors [viz., Marx and Engels]82 [were] not so foolish with their lasting interest in prehistory. You might look out some useful books on ethnology and mythology. All we have here is Bachofen, Reinach and Frazer, as well as Rohde and Lévy-Bruhl; Malinowski and Lowie's Cultural Anthropology are the up-to-date literature we have. We don't have Morgan's Ancient Humanity. …83

Just as the “synthesis” in the 1942 schema locates Marx on both sides of the antithesis (thesis: “The domination of nature can be explained by social domination”; antithesis: “Social power-relations can be explained by natural ones”), Marx should be located on both sides of the dispute between the “utopian” and the “realist” in the following manuscript (the thesis and antithesis of the ‘42 schema, respectively).

The core idea of the first draft of LII is the unity of the domination of nature and of social domination—that is, of class domination. As Horkheimer condenses above (§II.), in the ‘Outline’ to LII:

The domination of nature in human society is implemented as class domination. It is impossible to say which comes first. Self-preservation rebounds on the self.

If taken seriously, this idea would require nothing less than a reinterpretation of Eclipse and the Dialectic against more than half a century of broad consensus about the development of critical theory in the 1940s.

Lecture II. [First Draft]

We have devoted our first lecture to the concept of reason and the basic relationship between reason and nature. Today, we shall attempt a first approach to the problem of reason and society, or more concretely, how self-preserving reason makes itself felt in social development and social structure.

(A) Our major hypothesis is that the social equivalent to reason’s domination over nature is [the] hierarchical order of society, up to now inseparably bound up with the principle of organization which alone makes it possible to cope successfully with nature. To give you a very simple example: let us imagine that a group of primitive families, prior even to the crystallization of “tribes,” if forced, by fear of wild animals, to cross a relatively deep creek with a strong current. There arises a divergence of opinion on how it best can be effected, though there is unanimity with regard to the final aim which is deemed reasonable by all and actually corresponds to the principle of self-preservation. Some of the younger people may advocate swimming through the river, others may suggest putting some trees and loose wood from bank to bank to form a makeshift bridge, others may assume that the current is too strong for such an attempt and therefore suggest the construction of some sort of hanging bridge from jungle to jungle, of the kind we still find today in places like Ceylon. Let us make some more assumptions which can hardly be regarded as arbitrary constructs; first, that the last method is the most reasonable one insofar as it promises the safest crossing to the greatest number of people; second, that it requires a rather strenuous effort from the whole group, much more than taking the chance of a swim would, and that the majority of the group are not used to hard labor, living only from moment to moment, as it were, and that they are therefore reluctant to undertake the building which appears to them a tremendous enterprise that they fear they could never finish. Let us further assume that the advice to build the bridge comes from some of the elders of the group, having accumulated a certain experience in similar cases—they are acquainted with the dangers of the easy way—dangers which may well be greater for the old and infirm than for the youth. However this may be, the plan to build the bridge is finally accepted. The purpose of domination of nature by reason, namely, the overcoming of the natural obstacle by planned action, immediately calls for some organization. The elders whose plan has been accepted are probably best acquainted with the system of bridge building, while they are unable to do the manual work as effectively as the younger people. As far as the youngest are concerned, they are prone to give up the work as soon as something else, such as some game, catches their attention. If the work is not sped up, however, the whole group is in danger of annihilation. Thus a hierarchical order of primitive managers, of “supervisors”, who might well terrorize their underlings, and of actual workers, seems to be almost a matter of course. If the plan succeeds and the organization proves to work out satisfactorily, it may be maintained in similar situations and eventually become an institution. As a matter of fact it is even more likely that it has become institutionalized automatically before such a “rational test” takes place. This may be due to magical reasons, or to certain indifference of the primitives, which makes them accept any state of affairs when it has once come into existence. Thus, reason, as the guiding principle of the group’s relationship to nature, has led more or less automatically to a rudimentary social order. Since the rank and file workers of the group are naturally reluctant to work but are forced to do so by this organization, we may regard it as an immediate continuation of the domination of nature within the human sphere: the “nature” of the members, namely their readiness to follow every stimulus that attracts them momentarily, is brought under control by the rationality of the whole plan, namely by the survival interests of the whole group. At the same time, it is easy to see that in this rational hierarchical order the necessary maintenance of privileges, the development of antagonisms within the group, and thus an “irrational” state of affairs is almost implicit. We should regard history in much too harmless and too rationalistic a light if we interpreted this process as a deviation or deterioration of the aboriginal free cooperation of the group. For the primary solidaristic action is bound up indissolubly with the element of non-solidarity and privilege, and we cannot brand these elements prima facie as unreasonable. Thus, for example, the interest of the elders in building the bridge is stronger than that of the youngsters who might swim or jump, and yet, it might also be safer in the interest of the latter to build the bridge in order to avoid greater losses. However, the sacrifices required by the work are unequal. The youngsters have to work much harder and some of them may even drown while the elders sit and whisper [] and control the whole process. Yet at this stage, when there is not the remotest idea of an all-comprising organization of society, when, as a matter of fact, there is not even a knowledge of the concepts of society or organization, the whole thing might fail without this archaic division of labor, with all the irrationalities and injustices it necessarily entails. It is open to discussion whether there actually is at such an early phase such an impasse as represented in our imaginary case, or whether the assumption of this impasse is due to later patterns of thought which strive to justify the hierarchical structure of society as being reasonably unavoidable. However, such a question easily induces us to assume that what was primary and aboriginal is also good and justified—a thesis to which we should be careful not to subscribe. I wanted only to show you how deeply the concepts of reason and unreason are logically interrelated, and to show you with a simple example whose elements are open to common-sense understanding, what has grown through actual history into gigantic proportions and is practically impervious to immediate understanding—namely, that the rational organization of society has terminated in an irrational state of affairs. This fact of the intrinsic contradictions involved in the relationship of reason and society is the problem on which our attention will be focused in these lectures. If philosophy is more than the idle spinning of thoughts and has any true bearing upon our actual existence, it consists of a consciousness of such difficulties instead of skipping them by easy formulas and prescriptions.

(1.) Our original thesis that domination of nature by reason is concomitant with a hierarchical organization of society calls, on the basis of our previous discussion, for a certain qualification. This qualification refers to the relationship of domination of nature to societal domination. We cannot simply say that the latter follows automatically from the former, but we must admit at least that we do not know which of these comes first, whether historically or logically. This may appear to you as mere hair-splitting, since the fact of the interrelationship between those types of domination remains undisputed. Yet on this question whole philosophies ultimately depend. We all know the famous statement of Hegel that everything [actual] is also reasonable. No matter how we evaluate the statement, it is based entirely on the assumption that intra-human domination, and with it, all the sufferings inflicted upon mankind by history, are unavoidable, since they follow from the essence of reason itself insofar as it means self-preservation and the domination of external nature. Unless you recognize the primary formation of class relationships as reasonable in the sense in which we characterized the division of labor in our example as reasonable, the whole assumption of the reasonableness of history with all the apologies for the [actual] world must collapse. But although we have been forced to recognize the deep inter-action of extra- and intra-human domination, we have not reached any definite conclusion with regard to priority. For example, we have suggested that the plan of that archaic bridge-building came from a group of more experienced elders. If we reformulate our example in accordance with anthropology instead of leaving it entirely arbitrary, we may well assume that the authority of these elders, [...] a kind of priesthood was established, in some way or other, before the critical stimulation of the creek arose. We have mentioned that these elders happened to be more experienced than the rest of the group. If this experience, however, refers to something like a precedent of bridge-building—and otherwise [a precedent] could hardly be helpful [for us to consider] right now—the hierarchical order itself must have been precedent to the technological requirements which have been justified in our example as being rational, that is to say as expressing an adequate relationship between means and ends. All this, of course, is merely speculative, but it at least shows how intricate the relationship between reason and social order is at its very root. I wish to summarize the problem in two contradictory theses without suggesting a decision:

(a) Organization of men and all hierarchical and therefore repressive social forms are immediately necessitated by the struggle of man against his natural environment. They are inevitable, stem from the very earliest cases, and consequently can be overcome only by a gradual process of necessary steps which may finally terminate in a truly rational order.

(b) Repressive hierarchical relationships between men are prior to the domination of nature and the latter in its radical form is merely a consequence of [the former] or, as the psychologists would call it, a “projection” of intra-human features upon extra-human reality.

If the latter thesis be true, the idea of the necessity and inevitability of class relationships is a myth. The formation of such relationships might be attributed to some mishap, bad fortune, or catastrophe, rather than to any intrinsic logic of historical development. Hence the idea that this type of relationship may be overcome only step by step, according to the objective conditions prevalent in each epoch, is untenable. If some inexplicable illness has befallen mankind at a very early phase, it might be remedied at any time if only mankind as a whole would take its fate into its own hands.