Revised Collection: The Materialist as Polemicist (1933-1939)

Horkheimer's essays on Oswald Spengler, Henri Bergson, Theodor Haecker, Karl Jaspers, and Siegfried Marck. + Postscript: Adorno on Jean Wahl.

Part of the series on Horkheimer’s 1930s Essais Matérialistes.

[Revised ‘Introduction,’ added letters to ‘Appendix I,’ and added Postscript—3/25/25]

Collection: The Materialist as Polemicist (1933-1938). Table of Contents.

Translator’s Note.

Translator’s Introduction.

I. Review: Oswald Spengler’s Jahre der Entscheidung [The Hour of Decision] (1933)

Letter—Horkheimer, Re: Spengler’s Philosophy of History. (1935)

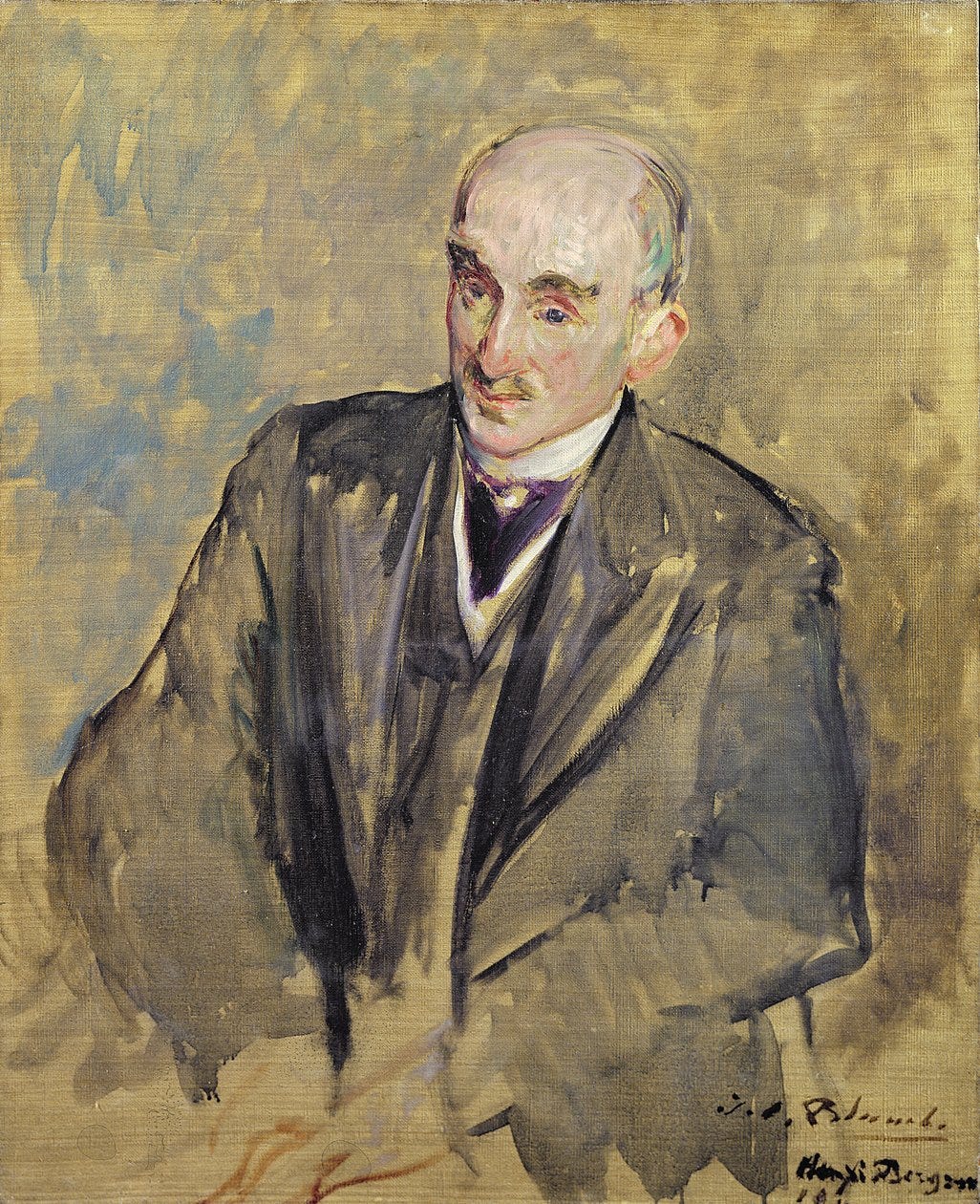

II. Review: Henri Bergson’s Les deux sources de la morale et de la religion [The Two Sources of Morality and Religion] (1933)

Letter—Horkheimer, Re: Bergson’s Principal Fault (1934)

Fragment—Horkheimer, Re: Irrationalist Philosophy and War (undated, ca. mid-30s)

Interlude: Between History and Theology (1935)

Letter—Adorno, Re: Theology for Atheists. (1935)

Letter—Adorno, Re: Fighters and Martyrs; Theory in Hell.

III. On Theodor Haecker’s Der Christ und die Geschichte [The Christian and History] (1936)

Interlude: Meditations on Metaphysical Sadness (1936/37)

Letter—Benjamin, Re: The Sadness of the Materialist (1936)

Letter—Adorno, Re: Justice to the Theological Motive (1937)

Letter—Horkheimer, Re: Injustice to the Theological Motive (1937)

Letter—Landauer, Re: The Future of an Illusion as Present (1937)

Letter—Horkheimer, Re: The Natural Subject of Reason. (1937)

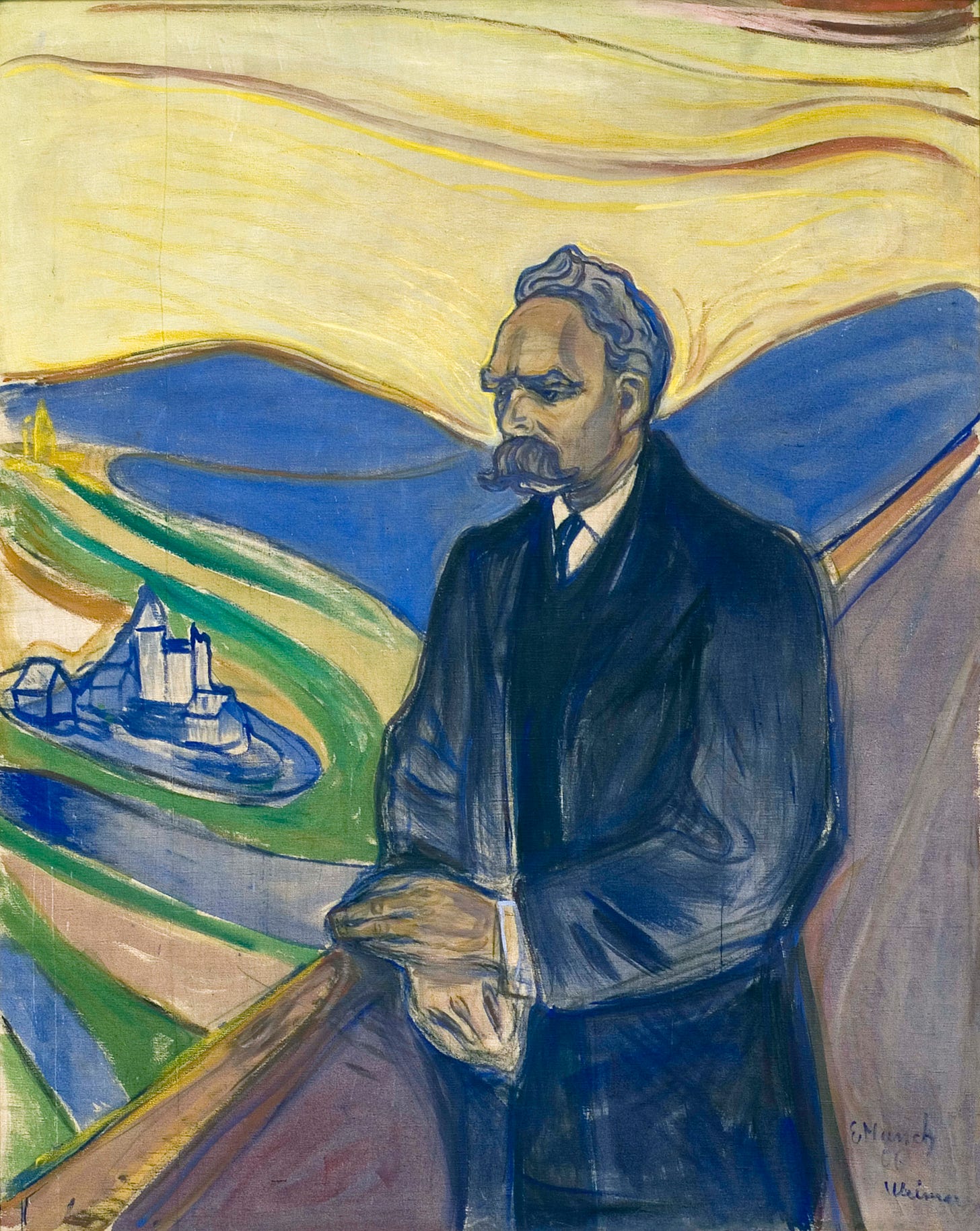

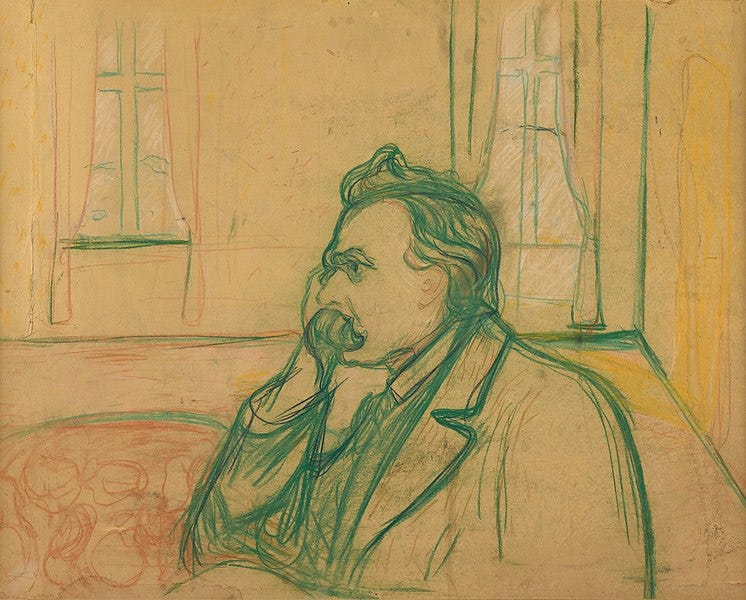

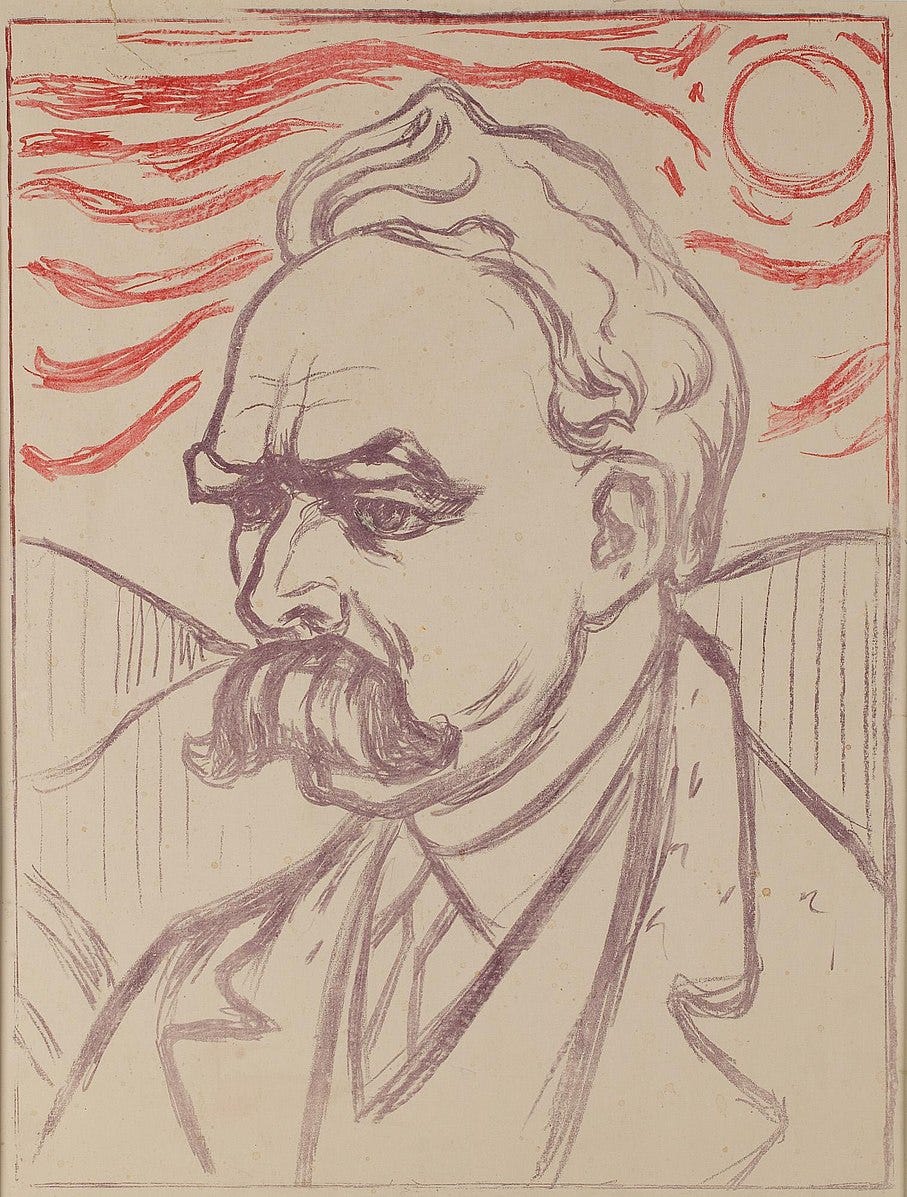

IV. Remarks on Jaspers’ Nietzsche (1937)

Translator’s note: The Spießbürger

Remarks on Jaspers’ Nietzsche

Letter—Horkheimer, Re: Nietzsche’s Critical Psychology (1936)

V. The Philosophy of Absolute Concentration (1938)

Appendix I: Dialectics of Decline (1937-1939)

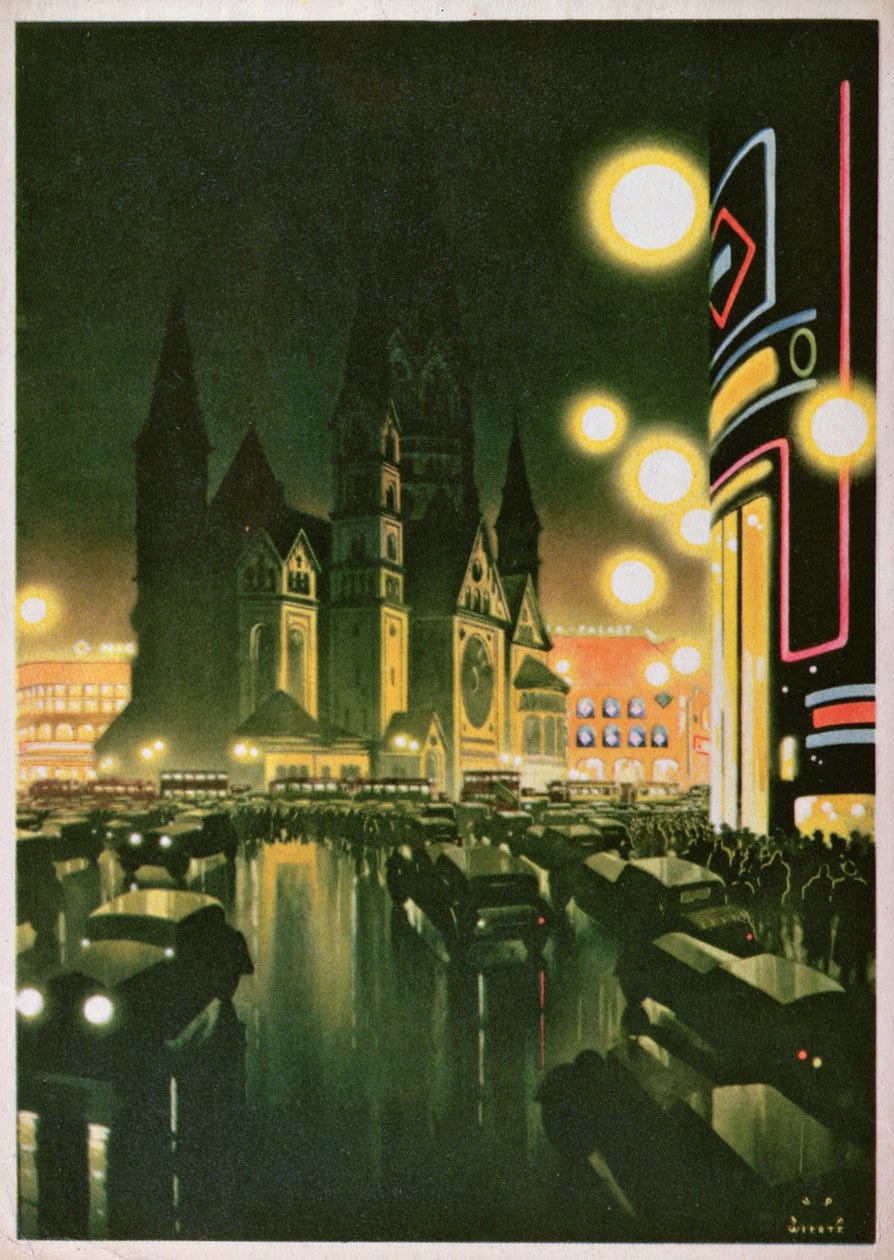

Letter—Horkheimer, Re: Exiting the Paris Exhibition (1937)

Letter—Horkheimer, Re: “Against Hitler” (1938)

Letter—Horkheimer, Re: Absolute Concentration and the Absent Grounds for War (1938)

Letter—Horkheimer, Re: “Chamberlain Wept” (1938)

Letter—Horkheimer, Re: Anti-Semitism and the Illusion of Happiness (1938)

Letter—Horkheimer, Re: Decomposition in Decline (1938)

Letter—Horkheimer, re: Theory and The Horrors of “In Deutschland, nichts Neues” (1938)

Letter—Horkheimer, Re: Semblance of Hope in the Time of Confusion (1938)

Letter—Horkheimer, Re: Method and Style in The Critique of Fascism (1939)

Letter—Horkheimer, Re: Atrocity as Social Principle (1939)

Letter—Horkheimer, Re: Theory Before the War (1939)

Letter—Horkheimer, Re: Dialectics of War and Peace (1939)

Appendix II: Horkheimer and Adorno’s Critique of Religious Socialism (1931)

[Horkheimer, Re: The Religious-Socialist Problematic]

[Adorno, Re: The Religious-Socialist Solution]

Postscript—Adorno avec Wahl

Review: Jean Wahl’s Études Kierkegaardiennes and Walter Lowrie’s The Journals of Søren Kierkegaard. (1939)

Adorno’s Letter to Jean Wahl, 4/30/1939

Translator’s Note.

The following collection consists of original translations of five previously untranslated polemics written by Max Horkheimer over the ‘first phase’ of the ISR’s exile, between the Nazi’s seizure of ISR assets in 1933 and the end of the ZfS in 1939 as the Nazis prepared for the invasion and occupation of France.

Max Horkheimer, “Besprechungen: Jahre der Entscheidung,” ZfS Vol. 2, No. 3 (1933), 421–424.

Max Horkheimer, “Besprechung: Les deux sources de la morale et de la religion.” In: ZfS Vol. 2, No. 1 (1933), 104-106.

Max Horkheimer, “Zu Theodor Haecker’s Der Christ und die Geschichte,” ZfS Vol. 5, No. 3 (1936), 372-383.

Max Horkheimer, “Bemerkungen zu Jaspers’ ‘Nietzsche.’” In: ZfS Vol. 6, No. 2 (1937), 407-414.

Max Horkheimer, “Der Philosophie der absoluten Konzentration.” ZfS Vol. 7, No. 3 (1938), 376-387.

A postscript has been added (3/25/25) with two original translations: first, of Adorno’s critical double review of Jean Wahl’s Études on (and Walter Lowrie’s edition of the Journals of) Søren Kierkegaard, which appeared in the final issue of the ZfS; second, of Adorno’s defense of the review in response to an objection from Wahl himself:

Theodor W. Adorno, “[Besprechungen. Wahl, Jean. Études Kierkegaardiennes.; Lowrie, Walter. The Journals of Søren Kierkegaard.]” in: ZfS, Vol. 8, No. 1/2 (1939), 232-235.

Adorno to Jean Wahl, 4/30/1939. Theodor W. Adorno and Max Horkheimer, Briefwechsel 1927-1969. Band II: 1938-1944. Edited by Christoph Gödde and Henri Lonitz. (Suhrkamp, 2004), 450-452.

Translator’s Introduction.

The basic idea of this collection is that the “double front” against which early critical theory defines itself in the 1930s is not, in the first or last instance, the philosophical front against metaphysics and positivism,1 but the political front against romantic, fascist reaction and rationalistic, liberal apologetic under ‘late capitalism.’ Following Horkheimer’s 1941 “Preface” to the penultimate issue of Studies in Philosophy and Social Science [SPSS] (~1939-1941), the ISR’s short-lived English-language successor to the Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung [ZfS] (~1932-1939), we can provisionally define ‘late capitalism’ as the fulfillment of the project of classical liberalism in authoritarian fascism, of the ideal of free market competition in the consolidation of monopoly.2 ‘Late capitalism’ designates the condition of the world in which Marx has been proven right:

Fascism feels itself the son, nay the savior, of the world that bore it. That world collapsed, as Marx had prophesied, because after it had reached a certain point in its development, it was unable to fulfill human needs. […] National Socialism attempts to maintain and strengthen the hegemony of privileged groups by abolishing economic liberties for the rest of society.3

To the extent that critical theory is defined by contrast to metaphysics and positivism, this is due to its reflexive appropriation of the ‘late capitalist’ historical problematic it shares with both, in opposition to their efforts to establish non-historical grounds, philosophical or scientific, for their respective theoretical standpoints.4 Early critical theorists confront metaphysicians and positivists not as combatants on the perennial Kampfplatz of philosophy but as participants in a shared field of social struggles which condition the entire process of theoretical and scientific production. In the introductory lecture to his 1926 course, Einführung in die Philosophie der Gegenwart, Horkheimer writes:

The Kampfplatz of philosophy [is] a part—and by no means the least important—of the actual social battlefront [sozialen Schlachtfeldes], upon which it [is] not merely illusorily, but actually, dangerous to make one’s appearance. […] [Mere] biographical information is, as a rule, just as abstract and idealistic as the history of ideas itself, in which the lives of philosophers are treated in large measure as independent and detached from the actual relationships with which one is concerned, such as those between thoughts, the notion of a real history of ideas is entirely untrue. Of course, the theories of any one philosopher are in no way independent in terms of content from theories they discovered about the same objects of inquiry, and which they followed. But such connections constitute only a minuscule part, often perhaps the least significant, of the relationships which must be considered in order to understand their thought. The philosopher lives in the actual world. Their philosophizing is part of their confrontation [Auseinandersetzung] with the actual world, as it has been formed in their given situation; moreover, philosophy itself fulfills an objective function, one which is in large part entirely independent of the philosopher. To lift ideas out of actual history and act as if one could adopt any propositions from one or other philosophy, however recent of an epoch they were written in, is inadmissible.5

The early critical theorists practiced a kind of ‘spiritual physiognomy’: interpretation as portraiture, each portrait the depiction of the conflicting social forces which animate the subject’s works from within, conflicts formed by the author’s continuous confrontation with their social context.6 The procedure reverses traditional physiognomy, which, for Horkheimer, is not just pseudo-science but a paradigm of reification. In a letter to Felix Weil in 1937, Horkheimer objects to Weil’s decision, made in desperation, to consult a graphologist about the erratic behavior of a romantic partner. Horkheimer’s response is a virtual rewriting of Hegel’s critique of physiognomy and phrenology in the Phenomenology of Spirit (§§309-346): the inference of certain character features from certain styles and strokes in handwriting, in graphology, or from certain facial features, in physiognomy, proves to be a confirmation of the prejudice of the graphologist or physiognomist; the arbitrary selection of certain observable features to serve as ‘symbols’ for certain non-observable character traits, as well as the wide variety of arbitrary ‘correlations’ between the former and the latter, derives a semblance of regularity from the fact that the graphologist and physiognomist have elevated common-sense platitudes, filtered through idiosyncrasies, into ‘scientific’ principles; the development of the subject of analysis is denied a priori; the social-psychological process through which the subject of analysis was formed becomes unintelligible as they are reduced to a partial impression of a temporary product of the same—caput mortuum; the trust in the ‘expertise’ of the graphologist and physiognomist as a guide to human relationships robs us in advance of the experience, let alone consciousness, of a kind of relationship in which our characters would be at stake in each renegotiation of a life in common.7

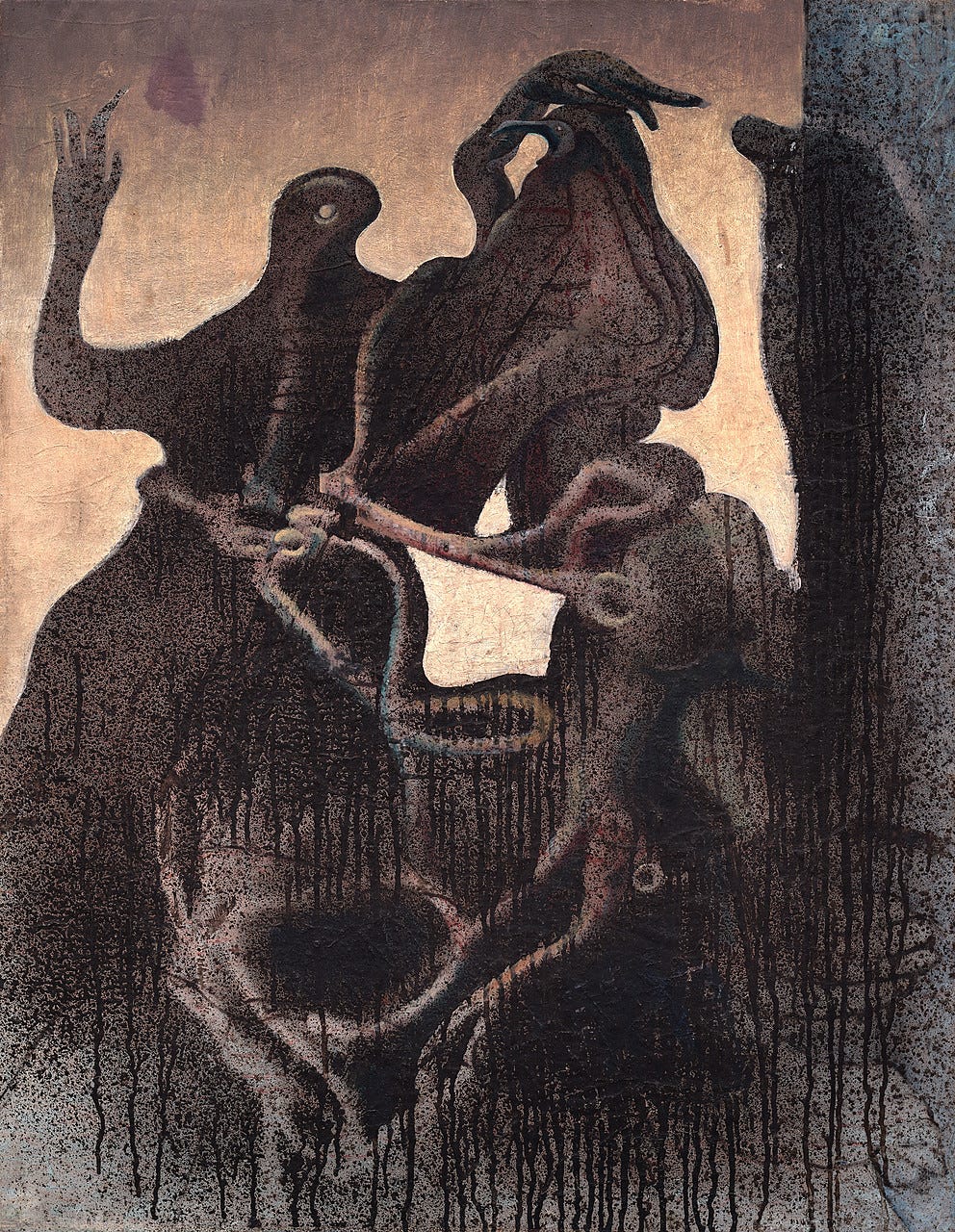

Graphology and physiognomy don’t just misunderstand human character, but mutilate it. They belong to the total social process which, Horkheimer says, judges individuals by those “external characteristics, which are connected to the bad side of current society,” at the expense of those “human traits that connect [them] to the future.”8 In “The Philosophy of Absolute Concentration” (1938), Horkheimer distinguishes the attitude critical theory takes towards human beings from Siegfried Marck’s ‘Neo-humanism’ by formulating the following task: “Philosophical anthropology must become a denunciatory physiognomy.” Denunciatory physiognomy denounces the society which seeks the advice of the physiognomist. The portraits of the spiritual, or denunciatory, physiognomist are only as optimistic as they are unforgiving. As Adorno and Horkheimer write in Dialectic of Enlightenment (1947):

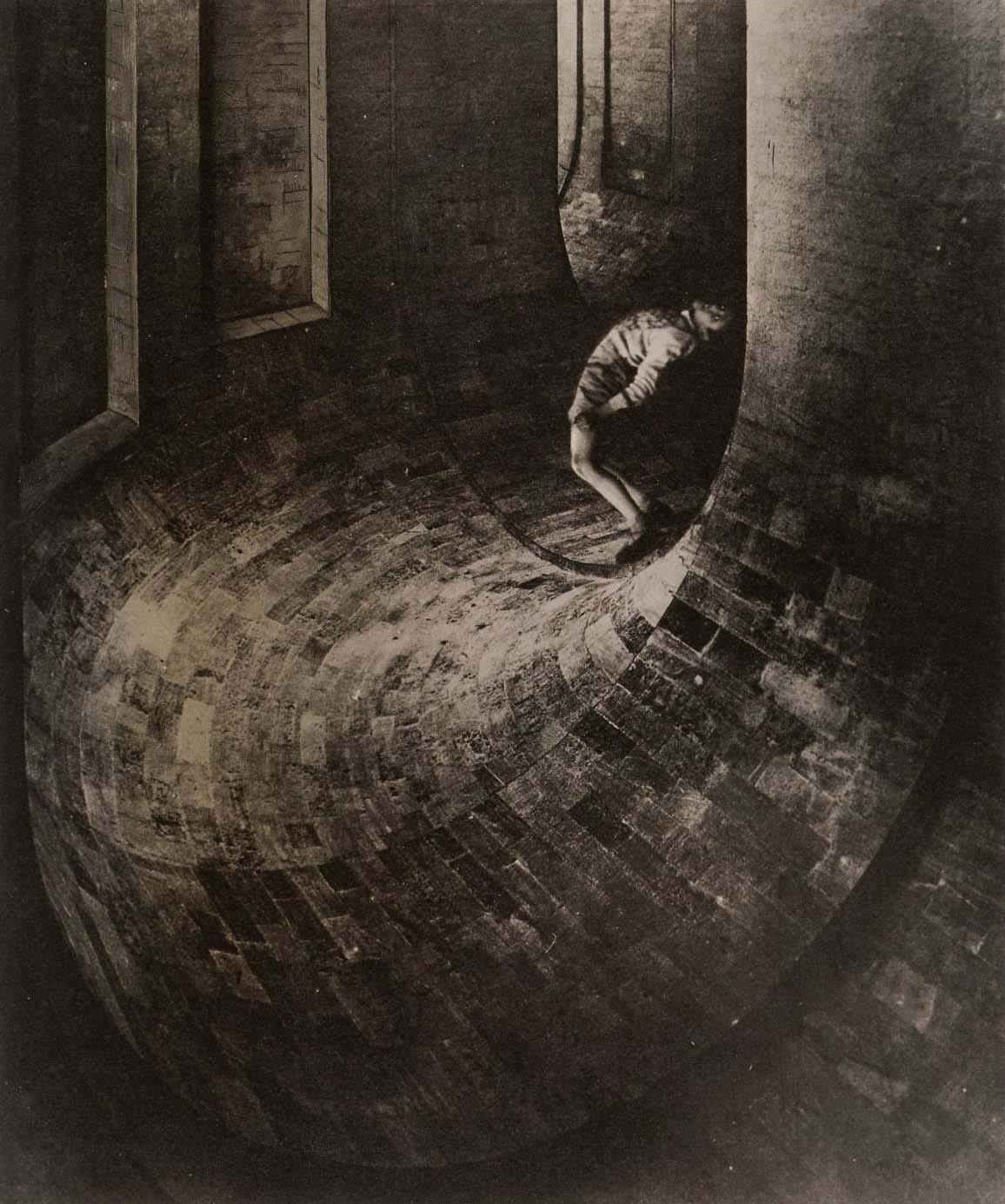

Stupidity is a scar. […] Every partial stupidity in a human being marks a spot where the awakening play of muscles has been inhibited instead of fostered. […] [T]he intellectual gradations within the human species, indeed, the blind spots within the same individual, mark the points where hope has come to a halt and in their ossification bear witness to what holds all living things in thrall.9

Neither misanthropic towards human potential nor philanthropic towards inhuman actuality, spiritual physiognomy offers negative images of betrayed humanity in the caricatures we’ve made of it—ourselves.

The following polemics are exemplary of this approach. Each portrait in this series has a central ‘dynamic motif’ of the same conflictual social forces frozen into another individuated expression.10 The primary tension is a unity of opposites between the extremes of, on the one hand, rationalistic or liberal apologetic for capitalist social domination—the reason which rationalizes ruling irrationality through appeal to unrealized moral or political principle, through the deferential formalization of the given in scientific procedure—and, on the other, romantic or fascist reaction to the same—the unreason which rises to enforce the order and restore the meaning the former can no longer guarantee, responding to the violence of liberalism’s unfulfilled promise of universality with the violence of its fulfillment for particularity.11 The tension between metaphysics and positivism in the crisis of the sciences is a mediated derivative of the social crisis tout court: “The contemporary insecurity in sociological judgments with respect to the future is only a mirror image [Spiegelbild] of contemporary social insecurity in general.”12 In the same 1926 introductory lecture quoted above, Horkheimer continues:

Philosophy and science in general are no longer the self-conscious expression of strong social forces which are certain of their power; rather, the exact converse is true: people have become insecure, people no longer know what to make of society, they need something to hold onto and they seek it with feverish haste whenever there might be a prospect of finding one. In the past, philosophy confronted a rotten traditional ideology with new, perhaps in a certain sense naive but in any case robust and magnificent, systems. Today, there is a lack of any generally recognized Weltanschauung, sanctified by tradition, which might help protect the status quo [das Bestehende], and the preeminent dangers to which this status quo is constantly exposed motivate the relentless search for ideologically solid ground. It is precisely the fragility of the wholly ideal character of the old Good which gives rise to the continuous attempts to produce the new, and which makes it appear so desirable. Therefore, in light of the enormous philosophical and semi-philosophical production of the present, it has never been so completely dangerless to express any ideological thoughts, however unusual they may be. […] And so, among its many achievements, we cannot expect exact science to produce a valid worldview, and one must, on one’s own initiative, seek one out, further and further—that is, one must ‘philosophize.’ […] This seeking and seeking-further, this discovery, systematizing and rejecting of theories, this unbroken endeavor to cobble together a tenable scaffolding for a worldview, this—as the saying goes—search for a spiritual content and intellectual meaning of life is the hallmark of the philosophical situation of the present. So far as there is an ideal ground for this state of affairs, it consists in the fact that the enlightenment, and all of those tendencies connected with the positive development of the exact sciences, have finally managed to not only dissolve the the sacred traditional contents of thought against which enlighteners fought in their heroic period before the great French revolution, but these same enlightened tendencies have also, and ultimately, directed their destructive force against the most indispensable ideological stock. When one considers the philosophical activity of the present and the ingress of philosophy into absolutely all areas of culture down to the last detail, one notices that all of these philosophical endeavors seem to be striving in one direction: towards the founding and validating of absolutely recognized values and truths, far above disputes of opinion. The famous resurrection of metaphysics in our day; all of the various attempts to renew positive religion; the great interest in extra-European philosophical, and especially religious, products of spirit; the reawakening of the scholastic dogmatists and their forefather, Aristotle; the apologetics for concepts such as personality, totality, unity, and so on; the entirety of phenomenology with its pretension to absolute essentialities [Wesenheiten] and essential laws [Wesensgesetze] in an eternally valid form—all of these currents are fundamentally motivated by the need to rescue or erect something absolutely valid in the midst of the universal destruction of everything which was believed and revered to date. It is the consequence of the science which arose from the enlightenment that no dogma or tradition was to be assumed valid, but to subject everything to examination, to dissolve it, to analyze it, down to its smallest elements and thereby destroy it. Today, as a result of the changed situation, many would like to reverse this course in many areas of life. There is an all-over aversion to mechanistic, rational methods; there is talk of turning back towards ideas and to seek these longed-for, unassailable ideal contents either in medieval or ancient history, or in other cultures (unlike in the past, primitive peoples are no longer considered undeveloped, but much more complex and of greater value than we poor Europeans)—or, they construct ideal and admiration-worthy entities on the ground of a new vision, a new perspective, a new belief. […]13

In the interwar ‘crisis of the sciences,’ the dispute between metaphysics and positivism is a refractory expression of generalized social crisis, recapitulating liberalism’s conflict with its unrecognized double in fascism within the sciences themselves. Using the device of analogy to introduce the explanation of a cycle, Horkheimer argues: just as liberalism provokes fascist reaction against it by the unreflected barbarism within it, positivism provokes metaphysical reaction by the unreflected metaphysics within it.

In the face of the flight of contemporary science, and the philosophy linked to it, to the opposed poles of research into all-embracing statistics and completely empty abstraction, metaphysics spoke out against this defect and kept a relationship, even if a problematic one, to the questions which science left behind. Like the situation in contemporary history, where the fascist opponents of liberalism took advantage of the fact that liberalism overlooked the estrangement between the uninhibited development of the capitalist economy and the real needs of humans, contemporary metaphysics grew stronger in the face of the failings of positivistic science and philosophy; it is their true heir, just as fascism is the legitimate heir of liberalism.14

Metaphysics, “dominated by the craving to bring an eternal meaning into a life which offers no way out,” turns to “philosophical practices such as the direct intellectual or intuitive apprehension of truth, and finally [to] blind submission to a personality,” and “as this form of social organization becomes increasingly crisis-prone and insecure, all those who regard its characteristics as eternal are sacrificed to the institutions which are intended as substitutes for the lost religion.”15 Positivism, “a pathetic rearguard action on the part of liberalism’s formalistic epistemology, which (…) turns into public obsequiousness in the service of fascism,”16 for “[t]he apparent rigor and precision of thought promoted” by it “fundamentally turns out to be the same objectivity that gives both workers and entrepreneurs their due in conflicts” and “testifies with sacred oaths to neutrality at the same moment when the victims are being annihilated by bombs of neutral provenance.”17 Early critical theory can no more be defined by reference to the ‘double front’ against metaphysics and positivism than metaphysics or positivism can define themselves in relative isolation from generalized social crisis without, in this very gesture of abdicating any reflexive appropriation of their genesis from it, handing themselves back over to it.

Understanding this structural dynamic of ‘late’ capitalist society gives early critical theory a singular, distinctive task. Formulated negatively, as Horkheimer does in several letters of the late 1930s, the successful liberal defense of capitalist society means the reproduction of the necessary conditions for the indefinite socialization of new Hitlers.18 For the early critical theorists, true anti-fascism is anti-capitalism, and true anti-capitalism is revolutionary socialism. In unpublished fragments written in the mid-30s, such as “Bourgeois World” [Bürgerliche Welt], Horkheimer is unequivocal:

The late bourgeois know that their ideals will either, and only, be realized through proletarian revolution, and within a socialist order, or will never be realized at all. If there can be any theoretical knowledge in the field of human, and social, life; if anything whatsoever has been manifestly proven by history—then it is this insight. […] Therefore, those who carry the bourgeois ideals not so much in their words but in their hearts find as little community with those miserable liberal and democratic reformers as they do with fascists themselves, and, conversely, both of these groups know very well that their enemy is simply uncompromising knowledge, and the attitude which corresponds to it.19

However, the conventional interpretation of the ‘Frankfurt School’ in this period is a highly de-politicized one, and consists of two theses: first, that the initial research phase of the ISR in exile (~1933-1939) is a continuation of the pre-1933 research program of study and criticism of bourgeois society, and seems largely unaffected by more pressing issues like anti-Semitism and fascism until WWII begins; second, that the ISR’s flight from Frankfurt in 1933 is supposed to have forced its core members and their close associates to reflect on their unexamined socialist sympathies for the first time just as it made their continued commitment to socialist politics impossible.20 The conventional interpretation (which I have elsewhere called the cliche of the “long farewell” to Marxism), in short, is that the ISR core’s work in the 1930s is untimely in the pejorative sense, and that their experience through the rest of the decade forces them to confront fascism and abandon socialism. My hope is that the essays in this collection will contribute to proving this interpretation untenable.

In these polemics, Horkheimer presents the “foundations” of early critical theory as open sites of contestation against liberal apologists for “the bloody and stupefying domination of capital” to the one side “and the fascist enforcers of its order” to the other.21 No other grounds are needed, nor sought. In his opening remarks for the “Discussion about the task of Protestantism in secular civilization” (1931), Horkheimer asks his interlocutors “accept the barbaric nature [das Barbarische] of my explanation in advance, for my reaction is relatively barbaric indeed,” insisting any theoretical diagnosis of the problems of the present refuse to pass judgment on ‘spiritual decay’ or ‘cultural decline’ before addressing itself to the ordinary brutalities of needless suffering from hunger or cold. As Horkheimer’s Regius writes in the Dämmerung:

There are people who will not be disturbed about the existence of evil because they have a theory that accounts for it. Here, I am also thinking of some Marxists who, in the face of wretchedness, quickly proceed to show why it exists. Even comprehension can be too quick.22

The rhetorical form of polemic is for the sleepwalking social theorists of late capitalism who, like the mourning father of Freud’s Traumdeutung, dream of deathless burning so as not to wake to the stench of the burning dead.

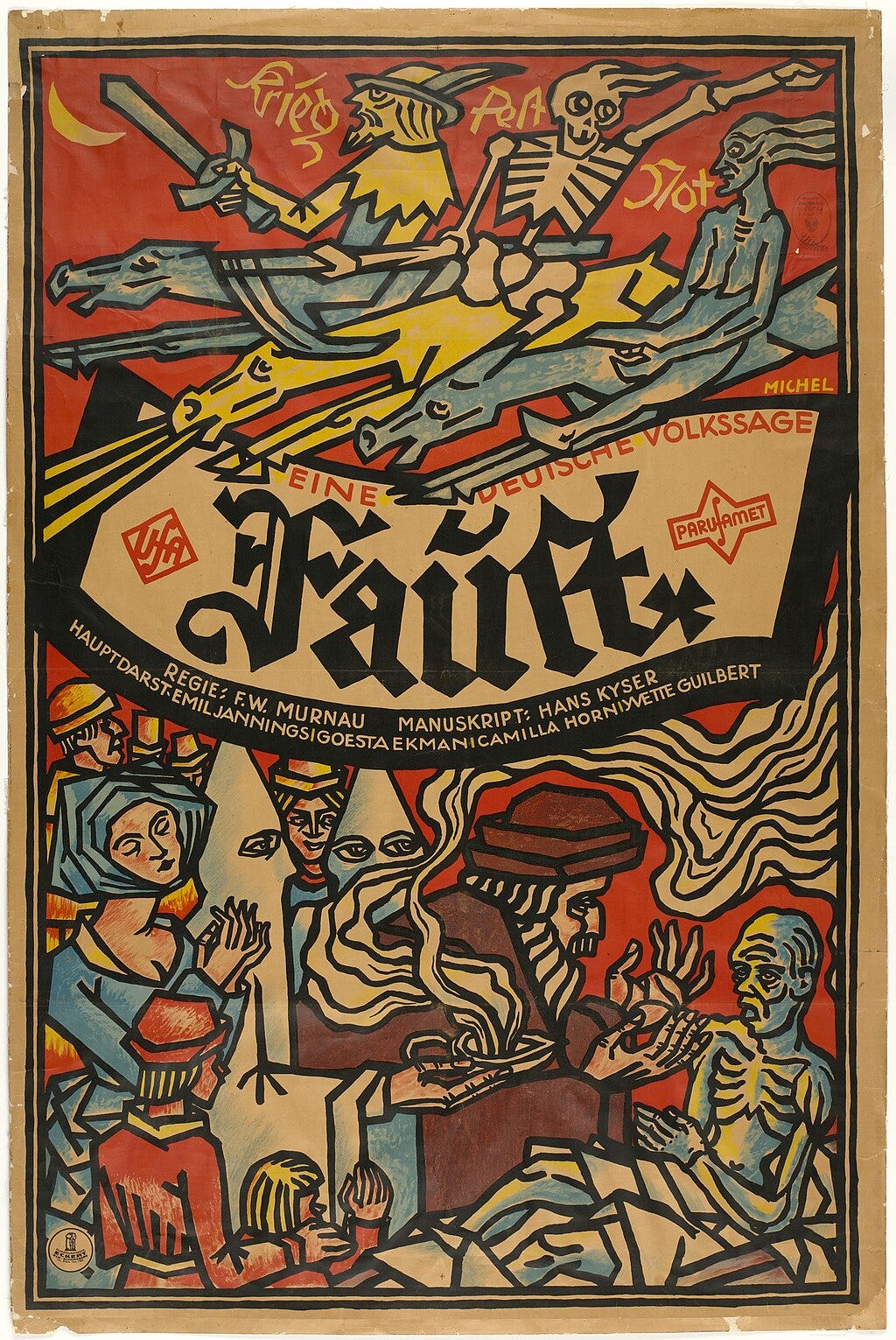

I. Review: Oswald Spengler’s Jahre der Entscheidung [The Hour of Decision] (1933)

Spengler, Oswald, Jahre der Entscheidung. Erster Teil: Deutschland und die weltgeschichtliche Entwicklung. C. H. Beck. München 1933. (XIV u. 165 S.; RM. 3.20)

The Faustian culture of Europe, says Spengler,23 is threatened by two terrible revolutions: the “revolution of the white world” in the struggle between classes [Klassenkampfes] and the “revolution of the colored world” in the struggle between races [Rassenkampfes].24 Spengler interprets the class struggle as the mob-revolt [Pöbel-aufstand] of all the most base and common instincts against the strong and noble race of the propertied (as for Spengler property is a matter of “race,” “a gift of which vanishingly few are capable,” the result of long breeding conducted by exalted dynasties). The economic-social forms and theories of class struggle are only a mask: just as it was not the economic misery, but merely “vocation-agitation” which capitalism brought down on the masses that drove the emergence of socialism, the goal of socialist movements is, accordingly, merely to overthrow “the brains and moneyed millionaires” to enjoy the latter’s wealth for themselves. The motives of class struggle are the greed, envy, and vengefulness of declassed intellectuals who use and abuse the worker as a suitable sell-sword for purposes of personal ambition. They have artificially cultivated the worker into a martyr of society, whereas, in actuality—at least since trade unions and worker’s parties have been the true rulers of the state, i.e., since about 1916—[the worker] is himself the exploiter of capitalist society. His wages are a purely political affair, violently fixed high above any need in order to reduce industry to ruins. Thus, the present world crisis was brought on knowingly and willingly by labor leadership, by the labor leadership which cannot grasp that there are “two kinds of labor”: “Labor which only a very few human beings of rank are bred for, and other [labors] whose whole value consists in their duration, their quantum. You are born into one as much as the other. Such is fate. This cannot be changed…”

Whereas the “interpretation” of this social development fills nearly the whole book, the “revolution of the colored world” is dismissed in just a few pages. The assault of the colored races (particularly Asians) against the white race, which has been deprived of its powers by the World War and degenerates even now into pacifism, is already underway. Rescue—if it still is possible at all—can only come from a new “Caesarism”: from the absolute dictatorship of a great individual, supported by the strength of a host from which the legions of Rome will be reborn. Germany is the soil best suited for this dictatorship which would come to the rescue, because here alone, in Prussiandom, is there a race strong and healthy enough for such a dictatorship. No scientific judgment may be passed on such a diagnosis. To the extent it departs from what is obvious, it gives expression to the personal feelings of the author and comprises his political confession. The negation of all which Spengler does not hold to be Prussian applies as well to those values which, at least since the time Christianity entered the world, have cast light on humanity. Goodness, justice, and humanity, which were, at any rate, the ideals of quite a few Prussians as well, appear to him mere weakness and lies. He rejects the idealism and materialism of modern philosophy in a single, sweeping condemnation, because he sees quite rightly that both are preoccupied with the betterment of human existence—whether freedom and happiness, or “the blossoming of art, poetry, and thinking.” The fate of history falls on the shoulders of more robust powers, and he thinks this good.

It is presumptuous “to want to master living history through bookish systems and ideals.” But all the objectives of the liberal bourgeoisie are bookish to him, and even Christian morality, to the extent it does not exclusively consist in mere resignation. “Christian theology is the grandmother of Bolshevism.” The history of the human being is the history of war, and will always remain so. Spengler sings its praises and calls this “valiant pessimism.” On the basis of such a spiritual attitude, he can even be enthusiastic about the present: “these are stupendous decades in which we live, stupendous—that is, terrifying and void of happiness.”25 It is evident he hates happiness; but not possessions, of course. The will to possession and property is only base among the working class, but not by any means among those already blessed with both. To him, rather, this [will] is “the Nordic meaning of life. It dominates and shapes our entire history, from the conquests of semi-mythical kings down to the form of the family in the present, which dies out when the idea of property does. Whoever wants for this instinct, they are not ‘of the race.’” There may be something right in this pseudo-materialistic conception of history. It is true that the fate of history does not depend upon intellectual forces, but “upon quite different, more robust powers.” It is true that no future deed can ever undo the blood and misery which compose the basic template [Grundtext] of history, past and present. It is true that despite all known and unknown heroes who exist in our “shallow” time, as they do in any other, existence for the greater part of humanity is a senseless struggle with poor results.

It is true that the lot of individuals in society is today determined, as in all chaotic periods, by the play of blind forces. But the hymn to meaninglessness, the delight in the fact that history is yet more natural history than human history, the triumphant gratification in thinking it will never become better and that all who believed it would were wrong, makes a mockery of any respect for the human being and its possibilities. This all-too-simple anthropology, that the human is evil from birth—as false in its exclusivity as is its opposite [Gegensatz]—today corresponds not to the “skepticism of the authentic connoisseur of history,” but only bitterness. Spengler’s work is a necromancy of Machiavelli, only without the latter’s belief in a happy future. Spengler is a realist; he stands on the firm ground of harrowing reality. What others brandished against the age as hideous accusation, he makes the guiding principle of the Nordic people he so reveres: property not for the sake of plenty and happiness (“whoever wills only contentment does not deserve to exist”), but for the acquisition of still great possession and still greater power, so on and so forth, for all eternity. This character has been depicted in literature—as Alberich, in Richard Wagner. “Schätze zu schaffen und Schätze zu bergen nützt mir Nibelheim's Nacht, doch mit dem Hort, in der Höhle gehäuft, denk' ich dann Wunder zu wirken: die ganze Welt gewinn ich mit ihm mir zu eigen!” The force which is embodied in Alberich is also the meaning of meaningless history which Spengler affirms. He speaks much of culture, but because this culture has neither the happiness of human beings nor even their betterment as its content, this culture becomes a hopeless mechanism of interlocking gears. Within it, joy is of no value: “Hagen, mein Sohn, hasse die Frohen!” The writing itself gives this barbaric frame of mind a consummate and grandiose expression.

Accordingly, the splendor of its language derives less from the depth or clarity of thought than from the imposing dimensions of its objects. Spengler finds it contemptible to concern himself with the small and glorifies the sublime—not, however, the moral sublime, which by no means escapes his contempt, but the mathematical sublime: the vastness of time, geographical expanse and distance, large numbers, the quantitatively immeasurable, in short, the concept of that which Spengler calls the Faustian, Hegel the bad infinite.26 His pathos is, therefore, especially shocking for those who are enthusiastic about pure ‘mass,’ not the ‘mass’ of workers about whom Spengler speaks with undisguised disgust, but the ‘mass’ which, whether serving as the form of the incarnation of years or kilometers, furnishes the ground for his scale of values. Even among the forces of politics, what impresses him, above all, is quantity. “Expansiveness is a power, politically and militarily, which has not yet been overcome…,” he says, referring to Russia, and repeats in reference to America.27 The changing content of politics only ever plays a minor role for him: politics is always about one and the same thing, sheer power! The superficiality of the book, which pretends to be a scourge of the shallowness of our time, is particularly evident in its fundamental categories.

Nietzsche’s hymn to man, beast of prey [das Raubtier Mensch] still had, despite everything, a social-critical undertone, which brought him into association with the impressionistic currents of his contemporaries.28 It was a protest against the growing inhibition of human forces through the ossification of the bourgeois order; within this hymn, solitary tendencies of the enlightenment still live. Spengler’s arrogant [bramarbasierende] elevation of the beast within man and states to heaven appears to be nothing more than a projection of the petty bourgeois philistine [spießbürgerlichen] experience of imperialist politics of the present into eternity.29 Because the little man sees the Völker are jealous of one another, but does not not know why, he makes the surface into its own ground and asserts mere robbery and lust for power is to blame; he confuses essence and appearance. Spengler’s enthusiasm for history, or how it appears in bad textbooks, as the sheer form of strength, conquering, punching-down, domination, for the ostentatious display of brutality both at home and abroad, for the elevation of barbaric contempt for law and justice into principle, by one who immediately breaks into tearful lamentations when he feels his own cause has been done wrong—all of these features of Spengler’s work render the exact outline of the caricature of the Prussian character unrivaled by those drawn by his declared enemies. This author has taken a legend seriously, and has modeled his inner self upon it.

His enmity towards the workers, indeed his misanthropy, is given such vociferous expression, as if he wanted to escape the accusation of possessing these qualities by making them into his very ideals. As the consummate document of a sensibility inclined towards sheer oppression, which has been petrified by concealed scruples into defiance and fabricates a theory out of the desire for domination [Herrschsucht], the book possesses some psychological and historical value. In no way, however, should it be regarded as characteristic for the authoritative, and in sociological terms extremely complicated, intellectual currents prevailing at present in Germany. Some features belong to the pre-war Junker spirit, the efficacy of which has today been severely impaired. A number in German criticism have already refused it even that.

Letter—Horkheimer, Re: Spengler’s Philosophy of History. (1935)

[Excerpt from: Horkheimer to J. Doppler, 5/2/1935.]30

Herr Doppler! Your letter of April 18th with the enclosed text31 has reached me at a time when the work before me is almost beyond me. While trying to secure the financial means for the continuation of our studies in a series of rather complicated negotiations, I have been able to finish a number of smaller works of my own and, in collaboration with other members of the Institute, have completed a manuscript of a large sociological anthology [viz., the Studien über Autorität und Familie]. Even now, however, I have barely a quarter of an hour left over for the most necessary correspondence. Therefore, I hope you’ll forgive me for only being able to skim through the draft of your dissertation on Spengler’s philosophy of history all too quickly. On the basis of this draft, naturally, it is hardly possible to see how exactly you mean to approach the matter. I am certain you will avoid a danger which some turns of your disposition might remind one of, namely—playing out a sociological doctrine of [social] situation [soziologischen Standortslehre] against cultural morphology. Relative to the efforts of the latest Wissenssoziologie to ascribe all cultural achievements in theoretical, artistic, political, or other domains to some so-called social situation, which is, moreover, very poorly defined,32 Spengler’s undertaking may still be called concrete. His attempt to bring what happens in spiritual domains into connection with the power politics of peoples and nations is certainly and highly inadequate. But the perspectives which he opens up in this way—and, above all, in a series of connections which he uncovers—may at the very least be of some limited service within the framework of a correct theory of history.33 As you yourself have mentioned in your exposé, Spengler has enriched historical research in many respects. Reading the Decline, for all of the indignation it arouses, at least expands the horizon of a thinking which has grown accustomed to the average histories. The Wissenssoziologie of the present cannot offer you this. But you know this as well as I do, and I am certain you will be careful not to make rushed classifications of ideologies and situations, or make all-too-sharp divisions between “objective” [objektiven] and “subjective” [subjektiven] conceptions of value in the Weberian sense.

Just as you are certainly not applying a static concept of a system in the attempt to “define the position of history within the system of sciences.” True, scientific cognition [Erkenntnis] has a determinate structure in any one historical instant. But both of the moments which condition this structure—the object of cognition and cognizing subject [Gegenstand und erkennende Subjekte]—are caught up in continuous transformation.34 Even if we were to call the theory of this transformation itself ‘History,’ there can be no doubt that history, grasped in such a way, is closely connected with certain practical interests. It is entirely conceivable that there comes a historical state of affairs in which cognition [Erkenntnis] centers not so much on that which transforms as on that which is relatively constant. Increased interest in history itself corresponds to the real struggles of the present, and this is no inducement to make history into metaphysics instead of natural science, as was previously the case. I will search for the critique35 you mentioned as soon as I find some time. You can imagine how difficult it is to find such manuscripts in my current situation. I hope it will come to light in the course of some of the clean-up operations I am currently planning, and, if so, I will send it to you immediately. [...]

II. Review: Henri Bergson’s Les deux sources de la morale et de la religion (1933)

Bergson, Henri, Les deux sources de la morale et de la religion. Félix Alcan. Paris 1932. (364 S.; Frcs. 25. —)

In his new book, Bergson does not merely restrict himself to the schematic application of his prior philosophical views to society, but instead provides a series of highly stimulating reflections on a number of social-philosophical questions. It is evident that he remains closer to the impressionistic origins of his philosophy than to the political function his basic thoughts [Grundgedanken] have since acquired by virtue of historical development. The intuitionism he helped to found now plays the role of diverting away from the theory of the tendencies of society as a whole; the new book shows that Bergson, in opposition to this, is concerned, albeit in a highly abstract way, with actual historical progress. In the spirit of French positivism, he explains morality and religion from the needs of society. The morale close is aimed at conserving existing social structures. As the natural tendency of every human individual to obey the system of customs which prevails in his group in perpetuity, it corresponds to ‘instinct’ in the rest of the world of the living.

This morality consists in the fact that the individual conducts himself as a member of those social units into which he was born. It binds him to his family and nation, and separates him from other families and nations. The universal love of humankind, or humanity [Humanität], is, according to Bergson, associated with the morale ouverte and must therefore not be considered an extension of more immediate feelings relating to instinct. The greater quantity of object corresponds to a difference in quality of affect. The morale ouverte appears to him as the momentary, unforeseeable incursion of the metaphysical stream of life into human history. The points of incursion are those great men, “certains hommes, dont chacun se trouve constituer une espèce composée d'un seul individu.” They give expression to a radically new feeling for the world, and this is imitated by many. The new is absorbed into the old circle of life and merges with it, at which point the circle closes once more.

Bergson does not recognize that the morale ouverte, on which, in his account, human progress depends, has, as much as the morale close, social conditions of its own. In accordance with the fundamental separation between intuition and analytical science in his philosophy, he separates the open, forward-facing, revolutionizing moral intuition from the system of customs which belongs to the self-preservation of a closed society. Thus, he fails to notice the fundamental dynamic of forward-driving and retarding moments within history, the dialectic of société close and ouverte. The distinction between open and closed morality corresponds to that between dynamic and static religion. In explaining static religion as a system of narratives, Bergson again demonstrates his affinity to positivist naturalism. [Static religion] is nature’s defensive reaction against the thought of the inevitability of death mediated by the human being’s ability to create fables, and is thus, so to speak, a purposive measure required by life which, in contrast to that of the animal, has has been endowed with intelligence. [Static religion] also promotes the subordination of egotistic goals to the general welfare, without, however, necessarily being identical with closed morality in development. The function of static morality is always directly intertwined with national needs. The tradition of religious narratives has a history all its own. Static religion, in contrast to closed morality, need only incorporate those social obligations without which every social bond would be torn apart.

Yet static religion is only the expression, the understanding-tempered formulation, so to speak, of the mystical certainty wherein the human being knows himself to be one with the stream of life, with the power of creation which transcends all individual life. Dynamic religion does not consist of the narratives which bind intellects to one another with regard to their continued existence, but in their identification with the life which each of us may discover within ourselves, the life which pulses through and beyond every fixed form. All legends, all gods are products of the creative striving from which the universe itself emerges unceasingly. The true mysticism does not stop at ecstasy: not only does it expound the contents of its ecstasies through its teaching, but itself becomes the power of creation in which the mystic immerses himself and expresses it through his life: “Sa direction est celle même de l'élan de la vie; il est cet élan même.” In connection with this doctrine of morality and religion, Bergson turns to consideration of future developments and says that “industrialisme et machinisme” has not brought humanity the happiness it once hoped they would bring.

Like the late Max Scheler, he believes Europe will succumb to overpopulation—indeed, that the whole world will, and will quickly—and so succumbs to the Malthusian way of thinking. A genuine Lebensphilosoph and metaphysician, he sees salvation as an inner conversion [inneren Umstellung]. He thinks “simple life” could replace the mechanism of the present if the material pleasures so sought after today were made to fade before a new mystical intuition. In one remark, however, Bergson says that the present needfulness [Not] of human beings comes from the fact “que, la production en général n'étant pas suffisamment organisée, les produits ne trouvent pas à s'échanger.” This thought could have led him beyond philosophy to science. “L'humanité ne se modifiera que si elle veut se modifier.” L'humanité, however, for the time being, is as little unified in will as it is rational in organization. The roots of this want can only be comprehended by means of a precise study of the most advanced economics and psychology. If simple life could help humanity, we would long since have been rescued; for the overwhelming majority of all human beings live in misery. As little as the finiteness of cognition [Erkenntnis] may be overcome by immersion in creative life without concern for rational science, social needfulness will just as little wither away through internalization [Verinnerlichung]. The intuition from which Bergson hopes for salvation in history as much as in knowledge has a unified object: life, centrifugal force, duration, creative development. In actuality, however, humanity is divided, and intuition, which penetrates through the contradictions towards unity, looks past what is historically vital, what lies right before its eyes.36

Letter—Horkheimer, Re: Bergson’s Principal Fault (1934)

[Excerpt from: Horkheimer to Hans Cornelius, 9/25/1934]37

At present, I am in the midst of completing a rather comprehensive critique of the latest book of Bergson’s, La Pensée et la Mouvant. He belongs, after all, to those few philosophers who deserve to be taken seriously. His principal fault seems to me to lie in the fact he does not successfully conceive the interaction of sensibility [Sinnlichkeit] and the understanding [Verstand] in actual science and therefore arrives at an unwarranted rejection of conceptual thinking. Such disregard leads him to create the myth of the Lebensstrom which flows through the world, a harmonizing fable in the most blatant contradiction with the actual course of the history of humanity.

Fragment—Horkheimer, Re: Irrationalist Philosophy and War (ca. mid-30s)

[On Irrationalism in Philosophy]38

The descendants of the old rationalism and empiricism have defended themselves against the increasing ostracism of thought, in part with very astute arguments. Some have even pointed out some of the social functions of irrationalism. Rickert, for example, describes Scheler's book on “The Genius of War,” which “serves to justify war as the climax of state effectiveness” (H. Rickert, Die Philosophie des Lebens, Tübingen [1922])39 as entirely consistent with the spirit of the Lebensphilosoph. “Anyone who not only sees that natural, vital life is growth, that it struggles against other life as check, but, at the same time, sees in this biological ‘law’ a norm for all cultural life, must indeed think like Scheler.”40

Interlude: Between History and Theology (1935)

Letter—Adorno, Re: Theology for Atheists.

[Excerpt from: Adorno to Horkheimer, 2/25/1935]41

I have read the new issue of the ZfS with great enthusiasm. I found the Bergson-essay42 quite extraordinary—the passage on the historian-as-rescuer [Historiker als Retter]43 moved me most profoundly. It is astonishing how completely here the consequences of your “atheism” (about which I believe you less and less the more fully you explicate it: for with every explication, its metaphysical force intensifies) run into those of my theological intentions, which, however uneasy they make you, nevertheless have consequences which are entirely indistinguishable from yours—I could even invoke the motive of the rescue of the hopeless as the central motive of all of my efforts without needing to say anything more; except, perhaps, to add to that the historical depiction of suffering and the non-emergence of the reader, [the reader] about whom you remain silent but is nevertheless the sole reader to whom such a history of creaturely suffering could be addressed. And, of course, I believe that just as not one of his thoughts would have a right to breathe if, when confronted by your atheism, it did not prove itself unconcealed and true, so too not one of your thoughts could be thought without this “what for?” as a source of strength through death, which burrows more forcefully into your cognitions [Erkenntnisse] the more tightly you seal them off from it; just as that ray of light which is not blocked by any wall but even possesses the power to reveal the innermost composition of the wall itself. I do not believe it would be a pointless and ideologically bourgeois [bürgerlich-weltanschauliches] beginning if we finally, instead of leaving this question unresolved (not as though it could be solved—yet we can renounce its solution even less!), talked this matter through to the end and unraveled it in full; and, for my own part, I could imagine all manner of social-theoretical consequences could stem from this, which would therefore also justify such a beginning when considered under the aspect of your present anti-metaphysic.

Letter—Adorno, Re: Fighters and Martyrs; Theory in Hell.

[Excerpt from: Adorno to Horkheimer, 8/21/1935.]44

Germany was more horrific than ever before, the country has truly become hell, down to the smallest details of daily life. As for the fates of those closest to us, we only know so much: Liesel Paxmann is dead.45 Official reports say she died of pneumonia at her relatives’; in reality, from more reliable sources, she died a political prisoner in Düsseldorf. No one even knows whether she committed suicide, as they reported, or she was murdered. Perhaps the Institute can make inquiries. —[Willi] Dörter has been sentenced to many years in prison for dissemination of communist propaganda.46 —[Heinz] Langerhans has disappeared; no one even knows if he’s still alive.47 —Even Günther Stern’s [viz., Günther Anders’] sister is in prison, serving a year-long sentence for harboring communists.48 —You’ve surely heard of the Dubislav case.49 It has nothing directly to do with political matters, but is only conceivable against the background of all the horrors of Germany: after his wife mysteriously committed suicide, he gouged out his girlfriend’s eye with a corkscrew. He’s in custody, now in a clinic where they are keeping close observation of his mental state, writing his autobiography under the title “Love makes you blind” [“Liebe macht blind”] (in this case, at any rate, it did the other). —This is the horizon in which I have had to exist for four months now. You can imagine, then, how I’m feeling.

I have doggedly applied myself to [a study of] your work, and have found some happiness in this. I have just made the connection between two of your insights: first, your theory of the dependence of prédiction on its object [Gegenstand] (against Husserl’s belief in “predetermined objects [Gegenstände] as such,” without consideration of whether their structure can or even must be changed); second, your critique of Bergson, who undialectically dissolves conceptual solidifications without at the same time assuming their cognitive functions [Erkenntnisfunktion], in other words against his undialectical dynamics. I regard this analysis a decisive achievement.

III. On Theodor Haecker’s Der Christ und die Geschichte [The Christian and History] (1936)

Lao Tse writes:

‘For compassion

In war brings victory,

In defense brings invulnerability.

Whomsoever heaven would establish,

It surrounds with a bulwark of compassion.’

The old Chinese man was already aware of this seven hundred years before our era. (…) I believe that the ancient Chinese were not at all stupid; doubtless, they had fewer prejudices; doubtless, they dragged around fewer ideas from German philosophy professors. Lao Tse says of the one who knows him:

‘Neither can one attain intimacy with him,

Nor can one remain distant from him;

Neither can one profit from him,

Nor can one be harmed by him;

Neither can one achieve honor through him,

Nor can one be debased by him.

He is, therefore, the noblest person on earth.’

And about the exercise of power:

‘Ruling a big kingdom is like cooking a small fish.’

He also asserts:

‘Where armies have been stationed, briars and brambles will grow.’

Further:

‘He (the good general) does not use force to seize for himself.

He places placidity above all and refuses to prettify weapons;

If one prettifies weapons, this is to delight in the killing of others.’

Further:

‘Weapons are instruments of evil omen,’

and,

‘Victory in battle, we commemorate with mourning ritual.’

I have indiscriminately chosen these words, words that he gives as advice to the rulers of his time. It is claimed that the rulers followed them. This was seven hundred years before Christ. We now live two thousand years after the birth of Christ. Progress indeed! For the sake of progress we now fly in airplanes, and a few years ago the civilized world danced at the sight of the first airship, just like an Indian tribe before its medicine man. The sad thing is that many are suffering, and the danger is that this era will devour us. We are prepared. We are laughing.

— Horkheimer to Rosa Riekher and Fritz Pollock, 8/22/1918.50

[English Abstract] If Haecker's book on History and the Attitude of the Christian [can] be considered as an index, there seems to be a strong humanistic current in present day Catholicism. Haecker develops in his book the Christian belief that history manifests the will of God, and that all wars, upheavals and revolutions really occur for the salvation of the soul of the individual. He opposes the modern trend to deify nation and race, and presents the elevation of man from his fall, and his return to God, as the eternal goal of all that ever happens. Because Haecker insists upon the intrinsic value of each single man, because he refuses to accept the ruling totalitarian ideology of the day, even the non-Catholic can go a long way with him in his humanism. Horkheimer, however, demonstrates that the connection between this kind of humanism and Catholicism is a very loose one. The deep understanding of human misery that is evident in Haecker's pages fits other convictions and persuasions just as well as it does a Catholic philosophy. Haecker's contention that to reject a sense and a meaning transcending the temporal world is to drive man to despair, does not invalidate the rejection of a supernatural significance. Despair is no argument against truth. Grief over the present is well justified; nevertheless an attitude is possible which permits of a positive cooperation in the historical tasks of the day.

For the true Christian, there is one, single, real goal in the finite: death, “the quiet of the grave.” Whether the work of human beings endures for seconds, years, centuries, millions of years: “That wind or storm, which will blot and wipe out the traces of all finite goals, will come. An intellect which does not realize this has yet to reach its own natural heights. But just because he has, this does not mean he can withstand it.” Madness is a mercy for him, lies and false doctrines, like that of the eternal return of all things, are his refuge. (30) Deliverance [Rettung] from such sinking is given solely through the Christian outlook and faith. The final goals are posited in the service of God, in the service of a return to God. God himself is the infinite goal. Though the world seems a hell, God alone is Lord of history, (117) his will all-powerful; he uses the wills of men and devils “for His unchanging purposes and goals.” (91) The role of peoples in the tragedy, or comedy, of history “is assigned to them by their Creator, the divine dramaturg and judge himself.” (129)

Haecker’s book51 was not written with the intention of establishing a new theory of history in mind. He seeks only to outline the Christian, or rather the Catholic, conception. Through clarity of thought and language, through limiting it to essentials, this short work, meant for a broad readership, is to demonstrate the vitality of Catholic thought. For all his knowledge of the complexity of historical-philosophical problems, Haecker never flees from the most decisive questions into the sheltered domains of specialist facility which, as a consequence of isolation, have only secured their irrelevance. He develops the Christian point of view as a whole.

All which has beginning and end, which exists, also has its history: all particular histories coalesce into Universalhistorie, which, once begun, will someday come to an end. Particular histories have an order of rank: “The history of a hero or saint is itself hierarchically higher and fuller” than that of the average human being (47); those of animals, plants, and things refer themselves “to the history of the human being as the center and purpose of creation” (43). God himself is just as historyless as are values and ideas. The fact that [God, values, and ideas] are realized or “embodied” constitutes the course of history and determines its meaning, which, according to the Catholic conception, consists in the elevation and exaltation of the human being from out of his fallen condition. Each individual must carry out this ascent for and by himself alone. Even when it is not individuals, but social groups which are the primary bearers of history (50-52), [history] is ultimately about the salvation of each particular soul. In connection with the salvation of persons, all events in human and extra-human history acquire order and meaning. Historical trajectories are, of course, subject as much to the specialized scientific methods of geologists, biologists, political economists, and psychologists as they are to the critical scrutiny of historians; nevertheless, they remain a meaningless multiplicity, a chaos, in the absence of the light cast by the Christian belief that, through the incarnation of Christ, the divine-human process is woven into the profane, whereby the latter acquires its true reality and infinite significance.

God, human, and devil are the active forces in this process. Though external events may play an important role in deciding whether the human falls prey to the temptation of the devil or entrusts himself to divine grace, the decision ultimately transpires in the innermost recesses of the subject for itself. The subject is located between two unequal powers. The evil one, within the boundaries assigned to it in the plan for the world, tries to seduce the human being to misuse the freedom awarded to him by the Creator; God himself, on the other hand, shows the human being the path to salvation through his Church. Whereas peoples [Völker] win their dominions and disappear one after the other, the Church will endure until the end of days. Even if, “as is evident,” many of her representatives abandon the path marked out in advance by the Gospel and flout the precept to conquer without weapons but by means of the Spirit alone, and to bless “those who curse you” (134), at least [the Church] still proclaims this principle in her preaching, and many of her servants have time and time again sealed it through their lives. The people of God, however, who will adhere to the Gospel to the end and pass into eternity, will not be that of a natural community, race, or nation which forcibly spreads itself across the world today, but rather—so we may believe—will be that of individuals who have come together from out of all peoples.

In opposition to the writings of a number of modern philosophers of religion, who spiritualize, dissipate, or even put to the side the content of their faith to the degree that the reader can only guess from the theological coloring of their style what, precisely, the author is gesturing towards, Haecker actually proclaim a faith. By virtue of its independence from the successful currents in our time, its fidelity to determinate ideas and, above all, through its indwelling longing for universal justice, Haecker’s word evokes our respect, even if it is deceptive. The ground of Haecker’s thinking—unlike that of many appointed functionaries of the Church—is the tension between the events of the present and the faith. In many passages, contempt for the contemporary worldview, which glorifies the mere powers of nature or nation or leader, is evident. The content of the mass delusion [Massenwahns] which enslaves entire peoples, which, it seems to us, consists less in the fact that someone may earnestly hang onto marketable follies than in the fact that everyone, given the custom of displaying whichever conviction [Gesinnung] happens to be in the lead at the time, is forgetting the possibility of an actual one—such content is revealed in language alone: “Eternal heroes, eternal peoples”—temporal eternities, contradictiones in adjecto! Haecker knows all too well that there is no judgment too false, no obsession too tasteless and subaltern it cannot be just the right thing for the consolation and pacification of the degraded human being. As if their subsumption and subordination to that which pretends to be the highest nation or race, the contemporary abdication of independence in thinking and acting, this self-misunderstood idealistic abandon, were synonymous with true humility! A world in which the obedient mass, as false collectivity, has become an idol, would do well to remember that, within the Völker themselves, history is originally and always driven further by individuals opposed to the inertial drag of that which exists. The condition of progress is “the at times often tragic dissociation [Loslösung] of the individual from his community” (79)—that is, the struggle within the national group [nationalen Gruppe]. And if “the participation of free human beings in the shaping of this world is, as a rule, overestimated by non-Christians, at least those in Europe” (128), as this Catholic declares, Christians, for their part, should not imagine that history is made by God or the devil alone, and that the human can change nothing essential. Change and progress lie, to a great extent, in the hands of human beings. It is given to us to enforce the politics of the good against the politics of the bad. Without naming it explicitly, Haecker characterizes the latter as the totalitarian state. This second meaning of the political—which “unfortunately prevails” (56)—is “the usage and manipulation of human beings as means, on the grounds of psychological know-how [Erkenntnis] or oneness in feeling [Einfühlung], for the achievement of some purpose or goal, whether just or unjust.” This is precisely the definition of modern mass domination [Massenbeherrschung]; the substance of true politics aims at the goal of “a just order among human beings.”

The book challenges the reader to decide on its content, to adopt a mode of behavior that has fallen out of touch with the spirit of the times when it comes to religious intuitions. Haecker rightly castigates that vague thinking which confuses the fact that, throughout history, contradictory doctrines have been defended which have the same degree of truthfulness with the [idea] of the existence of contradictory truths (13-14). He does not elaborate on the social ground for this laxity. The relativism which was characteristic of the bourgeoisie during its liberal phase is still characteristic of the bourgeoisie in its totalitarian phase, despite its unconditional manner of speaking and regimentation of thinking at present. The religion which dwells within its social practice is ever and always the vulgar, narrow-minded materialism of profit and power. By closing themselves off to all materialism in response, significant social groups have alienated themselves from the truth altogether: the idea of materialism itself has been displaced into a “higher” realm by classical idealism, evaporated into mere fiction by positivism, and disparaged as a mere means of domination by the heroic realism of our day. When today a demagogue rejects the principles and deeds of his clientele on the grounds of foreign policy, his words are sometimes accompanied by a wink of the eye to the seduced masses, which cannot be noticed from the outside. This wink, which says that only the bad intentions are honest, relativizes the determinate content of his words; it is the barren truth of his speech. So-called authentic culture already bears this physiognomic sign of the völkisch mass orator to come. Where religion is concerned, the facts of the matter have long been obvious: the bourgeois [the Bürger] believes passionately in its necessity, not so much in its truth. However, for Haecker, though he refrains from such an analysis, the word is no mere means to another end which accomplices or ultimately even enemies might divine—rather, the word is a serious matter for him. The humanistic Catholic is free of the spiritual alienation [Geistfremdheit] of the relativistic bourgeoisie.

The decision demanded by his way of thinking is somewhat tempered by the internal contingency between its two constitutive features: humanism and Catholic dogma. His proclamation of the infinite value of the person, fidelity to the innate rights of the individual (78), struggle against the ideologies of race, nation, and Führerdom—these moments of his thinking form the properties of a conviction and civilization in retreat before the breaking darkness and connect Haecker with those who struggle for a better future for humanity. This humanistic structure can indeed be drawn to the fore from out of the complex of the Catholic world of thought; Haecker’s conviction finds its footing in this great tradition.52 However, this Catholic philosophy is similar to the idealistic philosophy Haecker rejects in that its theses can ultimately justify any mode of behavior towards existing society, be it critical or apologetic, reactionary or rebellious, without contradiction—indeed, without any violence needing to be done to it at all. With the historical-philosophical theses of God as the Lord of History and the salvation of the soul as history’s goal can be combined with conceptions which run directly counter to Haecker’s progressive critique of the spirit of the times.

The determinate connection between these dogmas and their real historical problems is not fully and explicitly articulated within the dogmas themselves, but is in equal measure funded by those interests which dominate the church. The Catholic preachers of the World War and their successors, who appeal to the Gospel just as much as as the author of the “Afterword,” testify against the humanity which resounds in Haecker’s language.53 Nor are the great cultural achievements of the Catholic Church—the teaching in social politics of the Middle Ages, the all-encompassing rationality of the Thomistic Summas, and Christian art—any more characteristic of the Church than the bloody history of its landlordship and the Holy Inquisition. The terror which the Church, in alliance with the nobility, has fostered at various times in the course of its existence, is completely without the rational elements which motivated the use of bloody deterrence against the enemies of a more rational form of society in many progressive movements. But if revelation—whether in itself or on the ground of the intelligent arts of interpretation and separation—is so ambiguous in relation to the historical struggle between a better future for humanity and humanity’s ruin, then those who are concerned with this struggle will, with all due respect for Haecker’s humanism, maintain their equanimity in the face of his dogmatic legend, from out of which Haecker’s independence to the darker tendencies of the present only seems to emerge.

Notwithstanding their venerable age, the doctrines dredged up by Haecker are no truer than the opinions of any other religion or sect. Duration of tradition and degree of truth have no direct correlation. It is said that the Lord our God employs devil and human being alike for his eternal purposes, that no sparrow may fall from its roost without him having willed it (84), let alone a head under the axe of the executioner; it is said that angels, i.e., spirits without body, help or hinder the preservation of the world, that murder and manslaughter are to be passed along as inheritance until God prevails in triumph eternal: this whole mythos—partly comforting, partly gruesome—becomes no more rational by virtue of Haecker’s commendable truthfulness. Such belief may indeed confer meaning to actuality, but not actuality to meaning; it is disclaimed by history. The beautiful prophecy that “whoever dashes against the cornerstone shall sooner or later be slain by it” (62) [Matthew 21:44] is not one degree more trustworthy than its opposite: that even the righteous shall be slain [Ezekiel 21:4]. There is an old Chinese narrative which is far superior to the Christian legend in this respect. It tells of the fate of several princes, four good and two bad. The bad, tyrants and exploiters of the people, lead rich and happy lives until their end. The terror which they spread stifles any disobedience. After their death, one may speak evil of them, but:

“Whether we revile or praise them they do not know it; does it mean any more to them than to stumps of trees and clods of earth?”

The good, friends to their subjects, servants to their country, suffer failure and famine, invasion by enemies and uprisings within. They die in misery and exile. After their death, they reap the fame of ten thousand generations, but:

“Though we praise them they do not know it; though we value them they do not know it. It matters no more to them than to stumps of trees and clods of earth.”54

The narrative dispenses with practical application.

Haecker refrains from seeking evidence in the present of God’s triumph, which “aims for eternity, not for time” (84); but at the very least, “signs” of divine success can be discovered in history. The modest claim to credibility made by this Christian conception of history arises in the course interpreting such signs, which stands in sharp contrast to the dimension of other historical claims which have been made by the Church. The opinion, for example, that Napoleon’s retreat from Russia was connected with his excommunication and should be interpreted as “the consequence of the anathema of a pope” without regard for all other explanations of this military event, calls for the consideration of whether there are other heads of state who would be more agreeable to the Eternal than those who, instead of excommunication and the curse of unhappy peoples, have earned the blessing of a pope. Even if the meaning of all world-historical events, crises, wars, and revolutions were actually determined by their significance for the salvation of the soul, as Haecker imagines, the friendship of the Church has nevertheless provided a truly poor model for how this standard ought to be applied. The decent, human mode of behavior that Haecker’s book may encourage in some passages is, in any event, no more closely related to the Christianity which has been operative in history than are the worst heresies. The objection that one’s orientation towards human beings is not as important as one’s orientation towards God—this thought, which may seem obvious to the decent, human believer, fares no better than the opinions it impugns, and among which it belongs.

The point of view which is objectively opposite Haecker’s conception of history—a view which denies the supernatural meaning of history, without thereby losing the understanding of “the indissoluble connections of the whole and all its parts” (92) as the positivist pseudophilosopher does—is barely taken into consideration by Haecker. The “pure atheist,” he says, is “a thoroughly aristocratic phenomenon” (15), but this conviction “naturally” belongs to an “aftertype [Afterart] of theology” (89). According to this claim—which Haecker shares with Max Scheler, whom he otherwise fought ardently against—any struggle against the religious point of view is in vain, because then it is necessary that some temporal good (power, fame, money, pleasure) is posited in the stead of the highest, in place of God.

Despite the ingenuity theologians have always employed in making this argument, it may very well apply historically to the bourgeois who is, at base, indifferent towards religion and the spirit in general—and also to the “modern man of action,” a specimen Haecker especially hates—but in any case remains an empty assurance before the self-conscious materialist. The state of affairs for which the latter strives, in opposition to the Church, does not have to be reified and eternalized: community with the actual interests of captive humanity and the sharpness of dialectical thinking safeguard us from idolatry more thoroughly than obedience to the Church, though the latter may be infinitely superior to obedience to the so-called leader-personalities which is today so widespread. Haecker’s charge of ‘Aftertheologie’ seems to us to apply far more to theology itself, insofar it cheapens the ideas of highest wisdom, love, and justice by ascribing them to the Lord of History. The impossible service of making this absurdity credible is expected from theodicy, of which Haecker says God not only allows but wants from us (85)—yet even Leibniz only won a sad infamy for himself in this commission.

There is a possibility of comprehending history without taking on the futile attempt of transforming it into a process of salvation through mere interpretation. The good, justice, and wisdom, which appear possible on the grounds of theory, are not yet realized so long as they remain a mere image in the heads of human beings. Those who would actualize the image have no need to make a God of it; rather, they know that this good too, when actualized, will still have a history and will still pass away. The finite goals for which the fighters and enlighteners of all times have faced death are yet nothing like death, despite what Haecker imagines them to be, for they are not eternal. They are distinguished from death precisely because of the mortal measures of happiness for which these fighters died.55 They did not bow before the higher religious mathematics according to which a life of agony and a life of enjoyment are equivalent to one another and null in relation to infinity. It was rather the objectives of the prevailing injustice which they considered to be equivalently null, and so gave themselves up that others might live otherwise.

In contrast, the materialist of everyday bourgeois life and the devout Catholic, prepared even for martyrdom, have always had this in common: that their actions were essentially related to the well-being of their own person.56 The vision of eternal bliss among the early Christians, as well as the majority of those who came after them, is distinguished by duration, but not so much content, from the earthly purposes of the children of the world. Therefore, every now and then, both of these stances [Haltungen] enter into a singular combination in one and the same person; on balance, the Church tends to take the side of the greater property. The childlike faith which Haecker promulgates has not seldom formed the naive superstructure of an inhuman actuality in the course of world history. It belongs to the greatness and wisdom of Catholicism that it does not completely dilute the idea of eternity and detach it from material desires, as is the rule in Protestant movements. However, if the materialism of bourgeois practice in a certain way presents the truth of theology, the materialistic theory rejected by Haecker, which holds up a mirror before such practice, ensures the motives of theology are not simply forgotten, but rather sublated [aufgehoben].57 This critique of religion, in fact, revokes the theological hypostasis of the abstract human being by developing the concept of God from out of determinate historical relations. Such a critique understands this abstraction, animated and sanctified by faith, as a result of social dynamics.

In that human beings, it teaches, no longer confront one another principally as masters and slaves, but as free beings, and the life of the whole is renewed by means of exchange, they equate their activities, the products of their labor, and themselves, and thus arrive at the notion [Vorstellung] of the human being in general, i.e., the human being without determined time, place, and fate, which is consummated in the concept of God in the modern age. What is real are the historically determined human beings who are connected to this form of social life—namely, the subjects of that abstraction which reflects social existence only imprecisely and abstractly—rather than their content, hypostasized and eternalized. This is not to say that every thought-structure, every context of knowledge, is a socially conditioned illusion [Schein]; nevertheless, the concept of God in the last centuries proves itself to be bound to a transient form of social existence. But the theory which has been suggested here—along with all of the hypotheses, psychological and otherwise, it encompasses—does not prevent us in the least from considering Christian ideology to be a decisive cultural progression beyond certain pagan forms of religion, nor does it diminish or conceal the truth and scope of of the thoughts which are associated with Christianity. To the contrary. By negating the ideas of the resurrection of the dead, the last judgment, and eternal life as dogmatic posits, the human being’s need for infinite bliss is fully revealed and takes up opposition to the poor conditions of the earth.

It is not the case that the theoretical materialist, like the bourgeois materialist, must posit perishable goods as absolute: he knows only that the desire for an eternity of happiness, this religious dream of humanity, cannot be fulfilled.58 The thought that the prayers of the persecuted in their greatest need, that the prayers of the innocent who must die without their case being resolved, that their last hopes for a superhuman authority do not reach their destination, and that the night which no human light can illuminate will not be penetrated by the light of the divine either, is monstrous. Without God, eternal truth has no more ground or footing than infinite love; indeed, it becomes an unthinkable concept. But has monstrousness [Ungeheurlichkeit] ever been a valid argument against the assertion or denial of a fact? Does any logic include the law that a judgment is false just because consequence is despair? The error of imagining that “this small earth is set in a predetermined space next to a select and privileged star among the starry host,” this pious belief, which Haecker sees confirmed again by statements of “modern astronomers” and again “on the grounds of experience” (138), corresponds to a longing even atheists have long understood.