Translation: "Report on Professor Schmid’s Pasigraphic Experiment in Dilligen," by F.W.J. Schelling (1811)

Translation draft by James/Crane (Winter 2024/25)

Translator’s Note.

The following translation draft is an excerpt from a report by Schelling to the Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften [BAdW] (Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities) in Munich, through which he’d helped found the Akademie der Bildenden Künste (Academy of the Plastic Arts) in 1808; he served as its first general secretary from the time of its founding through 1820.1 Schelling delivered several of his most notable post-Jena lectures to the BAdW, including Über das Verhältnis der bildenden Künste zur Natur (On the Relationship of the Plastic Arts to Nature) in 18072 and Über die Gottheiten von Samothrake (On the Deities of Samothrace) in 1815.3 Like the latter text, which was meant to be a historical supplement to the first book—“Die Vergangenheit” (“The Past”)—of Schelling’s Weltalter (begun in 1810, revised through 1833),4 the “Report” is a presentation of the same from within the problematic of the philosophy of language. The connections between this “Report” and the Weltalter are manifold—not the least of which is Schelling’s defense of his infamous quasi-algebraic notational system for the Potenzlehre from its vulgarization by Schmid. This is the connection that drew me to the “Report” in the first place, and one I plan to explore in the second chapter of my dissertation on the Weltalter-project (and, time permitting, a future post here). In the rest of this note, I want to highlight only one connection in particular: the philosophical identity of philology and geology.

Already in the Vorlesungen über die Methode des akademischen Studium [Lectures on the Method of Academic Study; translated (1966) as: On University Studies] of 1802, Schelling juxtaposes philology and geology such that the perfection of each science becomes a model for the perfection of the other:

Nothing forms the intellect so effectively as learning to recognize the living spirit of a language dead to us. To be able to do this is no whit different from what the natural philosopher does when he addresses himself to nature. Nature is like some very ancient author whose message is written in hieroglyphics on colossal pages, as the Artist says in Goethe's poem. Even those who investigate nature only empirically need to know her language in order to understand utterances which have become unintelligible to us. The same is true of philology in the higher sense of the term. The earth is a book made up of miscellaneous fragments dating from very different ages. Each mineral is a real philological problem. In geology we still await the genius who will analyze the earth and show its composition as Wolf analyzed Homer.5

Focusing on the implications of this juxtaposition for the study of language, Ramey and Whistler (2014) call Schelling’s project a “geological etymology,” in the execution of which “Schelling establishes a geological model for linguistics based on language's capacity to make present the depths”—namely, of meaning or sense itself.6 As Whistler (2010) argues elsewhere, the 1811 “Report”—specifically, Schelling’s instruction to ‘cognize that which is physical in language’ to discover not merely an ‘analogy’ but a ‘connection’ between the history of peoples and their languages with geological history—justifies the reciprocal modeling of philology and geology by referring each to an identical ground from which they diverge: the (natural) history of catastrophes which originates and potentiates the self-recapitulating series of forms in nature (inorganic or organic) and spiritual formations in human history (such as language, art, and religion).7

Schelling writes in the ‘Introduction’ to the so-called ‘second version’ of the Ages of the World (1813) (hereafter: WA2):

Science [Wissenschaft], according to the very meaning of the word, is history [Historie] (ἱστορία). It was not able to be [history] as long as it was intended as a mere succession or development of one’s own thoughts or ideas. It is a merit of our times that the essence [Wesen] has been returned to science; indeed, this essence has been returned in such a manner as to assure us that science will not easily be able to lose it again. From now on, science will present the development of an actual, living essence. In the highest science what is living can only be what is primordially alive: the essence preceded by no other, which is thus the first or oldest of essences.8

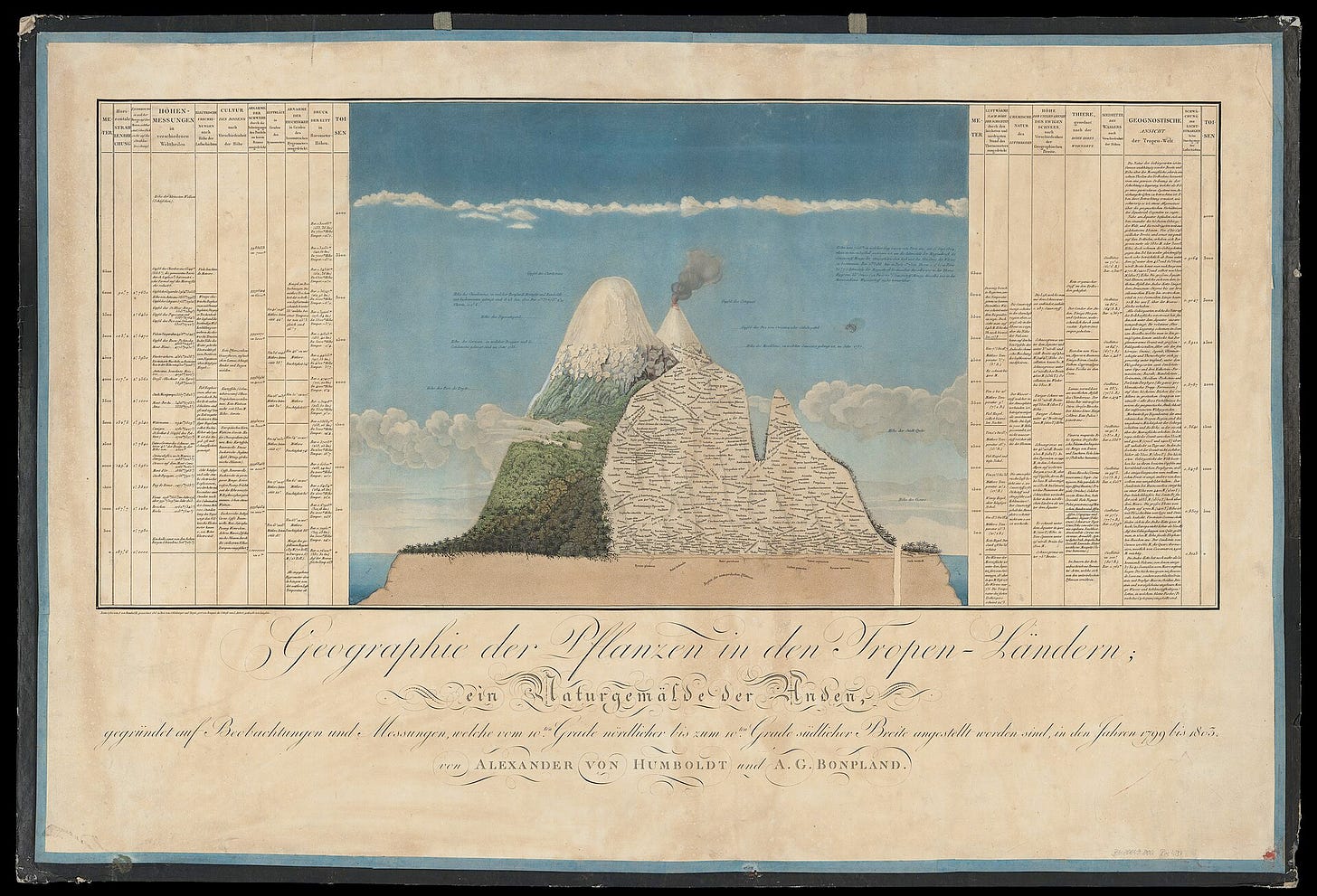

In the Ages, philology and geology, ‘in the higher sense’ of each, are mobilized as indispensable auxiliaries to ‘the highest science’ itself: the anamnesis of ontological genesis, or ontogeny, as such.9 For Schelling, the divergent series of natural forms and spiritual formations are nevertheless parallel. In the 1811 “Report,” Schelling proposes a homology between homologous mountain formations and homologous linguistic formations, positing a tertium comparationis between the comparative geology (or: geography, geognosy) and comparative ethnography in the work of Alexander von Humboldt.10 This homology (of homologies) is not just formal, but form-genetic: in the course of both human and natural history, there are catastrophic events which leave behind “monuments” which must be interpreted or “deciphered” to be understood; unless they are ‘lived’ from their origin through their end by the researcher, they will remain the caput mortuum of creation, even if, as is the case with so many monuments of natural history, they lie out in the open, well-explored and well-observed.11 These monuments are ruins: monuments to the destruction of monuments, traces of the erasure of traces. In WA2 (1813), Schelling elaborates:

Everything that surrounds us points back to a past of incredible grandeur. The oldest formations of the earth bear such a foreign aspect that we are hardly in a position to form a concept of their time of origin or of the forces that were then at work. We find the greatest part of them collapsed in ruins, witnesses to a savage devastation. More tranquil areas followed, but they were interrupted by storms as well, and lie buried with their creations beneath those of a new era. In a series from time immemorial, each era has always obscured its predecessor, so that it hardly betrays any sign of an origin; an abundance of strata—the work of thousands of years—must be stripped away to come at last to the foundation, to the ground. If the world that lies before us has come down through so many intervening eras to finally become our own, how will we even be able to recognize the present era without a science of the past? Even the particularities of a distinguished human individuality are often unintelligible to us before we learn about the distinctive circumstances under which the individual developed and formed. And yet we think that we can so easily discern the grounds of nature! A great work of the ancient world stands before us as an incomprehensible whole until we find traces of its manner of growth and gradual development. How much more must this be the case with such a multifariously assembled individual as the earth! What entirely different intricacies and folds must take place here! Even the smallest grain of sand must contain determinations within itself that we cannot exhaust until we have laid out the entire course of creative nature leading up to it.12

In short: the present is only legible in the context of a past it renders illegible by becoming present in the first place; formations which lie in the open lie buried by the formations they bury. This problem repeats at each excavated layer of stratification, unfolding a regressive sequence of without limit, each stage of which enfolds another regressive sequence without limit. In his late Monotheismus lecture sequence (1828/29-), Schelling will once again invoke Humboldt’s studies of homologous mountain formations in ‘connection’ with homologous mythological formations. The succession of mythological representations in the history of world religion, he argues, does not consist in ‘personifications’ of objects or forces of nature—rather, these representations are nature, or nature revenging itself ‘beyond nature’ on human beings for their separation from the natural world through the real repetition of natural process (cosmogony/geogony) in human consciousness (theogony/psychogony).13 Through the late lectures in the Historical-Critical Introduction to the Philosophy of Mythology (1941-), Schelling maintains:

The powers arising again inside of consciousness (…) and showing themselves as theogonic can for this reason be none other than the world-generating powers themselves (…) which take on once more, over and against consciousness, the quality of external, cosmic powers[.] (…) Not that mythology would have emerged under an influence of nature, of which the interior of man is on the contrary deprived through this process; rather, the mythological process passes, according to the same law, through the same levels through which nature originally passed.14

Thus, philology and geology, understood ‘in the higher sense,’ are, in their scientific autonomy, members of the organism of the highest science: Historie, the genesis of cosmos, earth, myth, and consciousness from the life of the divine.15 This science of philosophia proves to be a science of philosophy itself, as philology ‘in the higher sense’ is required in order to form a philosophical concept of the non-conceptual genesis in language of the fundamental conceptual formations which philosophers take for granted.16 Philosophy, in sum, becomes historical-critical self-consciousness of the unconscious genesis of consciousness, from the pre-historical foment of mythological representations to the abstract self-positing of philosophical self-consciousness itself.

Report on Professor Schmid’s Pasigraphic Experiment in Dilligen (1811)17

There have always been persons who have sought to reverse the unfortunate consequences of the Tower of Babel, such that there would be one language in the world again, or at least one script understandable by all peoples. The latter is what Professor Schmid in Dillingen seeks to accomplish.

The author's concept of pasigraphy.

One must do him the justice of acknowledging he does not set out to find a universal means of correspondence like other modern pasigraphers; setting such usage far aside, he starts from the idea of a script which is not accidental, but universal by nature. Herr Schmid explains as follows: the script or the sign [Zeichen] must be an immediate imprint of reason itself, signifying human thinking in content and form. If the natural system, the necessary concatenation and gradation of our thoughts were to be found, then, says Herr Schmid, the script, which would be an imprint of this connection, would prove itself to be a script for all human beings and all peoples.

[Comparison of this concept with the Leibnizian idea.]

Herr Schmid finds a significant coincidence between his experiment and the Leibnizian idea of a universal characteristic [Idee einer allgemeinen Charakteristik], and indeed makes it clear in his words that he has executed that which Leibniz only thought. This is doubtful, however, on the following grounds.

a) It cannot be assumed that Leibniz had in mind a merely logical genealogy of thoughts, and only wanted arbitrary, not necessary, signification [Bezeichnung] for them. Already, the expression ‘universal characteristic’ indicates that Leibniz was thinking of something signifying within the things themselves, of a true Signatura rerum. Herr Schmid is not the same in this respect: he would not only like to offer some of his expressions as significations of the things themselves and their relations (e.g., his five potencies [Potenzen]), but then creates his signs according to purely arbitrary logical subsumptions regardless.

b) Leibniz states that his universal characteristic would have something of an algebra to it, that it would contain a kind of calculus, so that drawing conclusions in this language or script would consist in calculation, and the errors of these conclusions would be errors of calculus. It is clear, however, that a calculus is only possible with signs which are at the same time the thing itself [die Sache selber]. If the a + b or the dx and dy of analysis were the mere recollection of an object, but not the object itself, all calculation would cease. Herr Schmid's pasigraphy shares nothing with algebra except the expression “potency”—perhaps not even borrowed from it directly—[his pasigraphy] cannot be elevated into a calculus because the signs within it are not not equivalent to the concepts themselves, but are in actuality mere signs.18 Note: an attempt to make calculations with Herr Schmid’s signs lead to inconsistencies and compelled him to confess that his pasigraphy is not, in fact, a kind of calculus.

[Value of the Execution.]

a) Regarding the Thought-indices.

If Herr Schmid has much too high of a concept of his experiment by comparing it with Leibniz’s, he seems to sink even lower in his execution of it, since the so-called thought-index [Gedankenverzeichniß], which he claims must be based on the strictest requirements of science, is neither scientifically grounded, nor grounded on internal necessity, nor even on the foundation of correct individual concepts.

It is not scientifically grounded.

He has no other proof for his five basic concepts [Grundbegriffe] of matter, plant, animal, human, spirit, which he views as five potencies of the potencyless thing [Potenzen des potenzlosen Dings] or of the thing in general—a thought which, it seems to me, has been borrowed from some crude product [rohen Produkt] of recent philosophical literature—than the question: whether there is something that cannot be brought under these five concepts (with regard to which the general concept of form is an example, which would be too limited if brought under the rubric of matter).

It is without inner necessity.

The position any one concept receives in the series is determined merely by whether it can be subsumed under a certain other concept, but not whether it must be subsumed under it.19 From this arises entirely random connections which have no more of a ground than the combinations arising from the association of ideas. For example, ships are brought under water because they float on top of water, but fish, which live in water, receive an entirely different position.

It has no correct concepts for its foundation.

For example, it is taken for granted that matter is absolutely lifeless, and in which everything proceeds by pressure and impact, although the thought-index also contains a rubric for “dynamic forces”; in the treatment of physical concepts, neither the requisite knowledge of science nor the requisite scientific precision is demonstrated. It is evident the author was just in a hurry to bring all of the concepts into connection as quickly as possible, no matter where, without much concern for the manner in which they were connected. With respect to developing the natural connection between our concepts, no merit can be attributed to this experiment in pasigraphy. Though the author has a higher concept of his undertaking than most, or all, of the more recent pasigraphers, it is evident he has not yet been able to achieve it in execution.

b) Regarding the signs.

In a true language or script of reason, the signs must not be accidental or arbitrary, but necessary. Anyone who regards such a script is possible must also believe in a natural connection between the sign and signified, a view which itself seems in any event to be deeply imprinted on human beings. Why else would so much always have relied upon words, in religious and political ceremonies, so much so that the success of whole undertakings was believed to depend on them; where else does the belief come from, widespread among all peoples, in a magic which could disclose the higher essence of things, heal the sick, and compel spirits to come forth through words; or even in general the opinion which ascribes physical effects to words. Apart from these particular kinds of representations, the philosopher cannot help but assume an original, albeit for us now unfathomable, connection between word and thing, because without such a connection all human language would have to be seen as the work of either the blindest chance or the most unruly arbitrariness; both of which are assumptions equally antagonistic to the philosophical spirit. In the eyes of most, this philosophical ground would be easily overcome by one taken from experience. What do the words used to signify ‘sun’ in Hebrew, Greek, Latin, and German—what do Schaemaesch, ἥλιος, Sol and Sonne—have in common with one another except one letter at most? But here alone, on deeper reflection, a side of linguistic research [Sprachforschung] becomes apparent which has previously been considered only little, if at all. The expressions of the original languages [Ursprachen] (for we cannot speak to those which are mere gibberish, namely, any idiom which has arisen through corruption, such as French and Italian)—the expressions of the original languages, I say, are far more indicative of the essence of things than we imagine. Just as the philosopher, for example, does not seek knowledge of the sun as such [die Sonne als solche], i.e., insofar as it is an external thing, but of its essence—the sun of the sun [die Sonne in der Sonne], as it were—, so Schaemaesch, Helios, Sol, Sonne did not originally mean the external sun, but something else that was esteemed to be the essence of the sun, and after which the sun was named. From the higher point of view on things, however, as is well-known, neither all human beings, nor all times, nor all peoples are on the same level. At a later date, I could perhaps communicate to the academy a series of observations I have made in this regard about words, particularly about substantives [Substantive] in our German language, which, as Leibniz once said, is a born philosophy. Anyone who has not conducted such inquiries would find it unbelievable that such an organic system of thought, such profound connections, are expressed in this language, often in single words.

The closest relative of the word is the figure [die Figur]—also in the external or physical sense [of ‘figure’], as in the now well-known sound-figures [Klangfiguren];20 but the power of the word was also ascribed to the figure, and not only out of enthusiasm [Schwärmerei]; the oldest scientific view of geometry, as it is found in the commentaries of Proclus and, more recently, in the works of Kepler, ascribes to figures an essential significance. One need only recall the five regular bodies which the Pythagoreans regarded as figurae mundanae, and which, according to Kepler, were supposed to signify the intervals of the planetary orbits. The Pythagoreans assigned the cube to earth, the pyramid to fire, the icosahedron to air; indisputably a pasigraphy entirely different from the most recent. [In the most recent system,] the figure is paired with a number; as unfathomable as the Pythagorean number-system now seems to us, the unbiased historian cannot help but assume there was a very real meaning in it. In any case, it must appear far greater to us that Pythagoras believed that spirit, idea, form were represented by the unity [Einheit]; otherness, matter through the duplicity [Zweiheit] (the binarius); and the body, composed of matter and form, through the ternary [Ternarius]; that he generally assigned the numbers derived from the one to spiritual objects because of their indivisibility, and those derived from the two to material objects because of their divisibility; this, I say, is entirely different from expressing ‘matter’ as C1, ‘plant’ as C2, and ‘spirit’ as C5. The assertion that “even science could not establish anything more thorough” is [cut down to size] through such considerations.

According to Herr Schmid’s own explanation, his signs are merely means; all natural reference to what is being signified ceases; or, rather, the author is inconsistent in this regard as well: one and the same sign is asserted to be necessarily valid in one moment, and conceded to be only arbitrarily valid in the next. Thus, for the author, ‘Spirit’ is in actuality, not just according to its sign, the fifth potency of things in general; among metals, gold is designated by the fifth potency as well, but it is not thereby asserted that it is related to other metals in the way ‘Spirit’ is related to ‘animal’ or ‘plant.’ In Schmid’s script, “philosophy” extends only to the ordering and sequence of the most general thoughts; thus, to call the script “philosophical” would be a real misuse of the word. Philosophy has as little a part in it as it does in any other arbitrary invention, for example, a cipher script [Chiffernschrift]. Overall, the ‘philosophical’ is only a cloak thrown over the matter from the beginning; later on in the execution, the experiment sinks to the usual artifices, the conventional signs of the common pasigraph.

[…]21

[Further Utilizability. b) As a means of inducement to better invention]

In Germany, mediocre, and indeed even bad verse had to be written, be met with joy and the approval of the public for a time in order to awake true and excellent poets. Perhaps it is a similar case with pasigraphy. This hope naturally depends on the view one has on the possibility of a universal script and language. Many things are highly desirable and keenly desired, though they have never yet come to fruition. To this kind of thing belongs the wish to make gold through the transmutation of metals, to find a universal remedy against the host of diseases, a potion of immortality, and the like. Perhaps the idea of pasigraphy belongs to the same class of things, and its execution should therefore also be sought through similar means and in similar ways. Just as making gold is not so much a matter of finding gold itself, but of finding the gold of gold [das Gold des Goldes], or that which makes gold gold [was das Gold zu Gold macht], finding a language as understandable around the world as gold is would really be a matter of finding the language of language [die Sprache der Sprache]. If it is permissible to consider possible a script which would not be accidental or conventional, but which would be universally understandable by its nature, then it must be even more permissible still to consider possible a language of this kind, and it would be far more natural, here as elsewhere, to proceed from language to script rather than proceed in the reverse direction, as Herr Schmid does, from script to language.

The thought that there is a language of nature [Natursprache], which, when encountered and actually spoken, would be immediately understandable to anyone else, and even seem to speak to him in his own language—namely, through the unlocking of the inner ground of all languages. This, then, is what pasigraphers want to achieve with their script, which should read as French to the Frenchman, Italian to the Italian, and Turkish to the Turk. How many have used the expression that nature speaks a mute language, or that there is something eloquent in every shape, every color, every tone of nature, without realizing they are saying each thing in nature is only a suppressed word which cannot express itself, and that the human being is only the mouth, the tongue, the expressive organ [das aussprechende Organ] of the already existing word whenever he gives things their names. Almost as common is the expression that every creature is the expression, i.e. the word, the articulation of a determinate idea. In this, the objectivity of language, or its first ground in the essence of things themselves is clearly recognized. The typical view of language is that it is something subjective, fundamentally arbitrary, and, therefore, only learned from without, whereas it has a necessary, inner ground, and comes to the human being from outside of them as little as any other science or art, and rather gushes forth from the depths of his own essence. Is poetry anything other than a higher language, and from whence does it come if not from the innermost of the soul? There are many known cases in which someone in a state of somnambulism composed poems which they could never have produced in an awakened state. Strange observations of a similar kind have been made about the human capacity for language in all times, which point to a natural ground of all language, a few of which I will cite here. The renowned physician Johannes Fernelius (in his book de abditis rerum causis Lib. II, p. 223) mentions a patient rendered prostrate by convulsions and who, in this state, and who was otherwise fully of sound mind, delivered speeches not only in Latin, but also in Greek, though he had never learned the language. Carpentarius (whom Borellus cites, in the Obss. medico-physicis rarioribus p. 153) narrates the same of a bishop, who did not understand any Greek either, which is not so unbelievable, and yet spoke it while ill, which is somewhat more difficult to believe. The well-known Aristotelian Petrus Pomponatius assures us (in his book, de incantationibus) that he had seen the wife of a shoemaker in Mantua who, when ill, spoke in various idioms she had never before understood and which she forgot once she had been healed by a doctor (whose name he provides). The same book refers to similar remarks by Aristotle and Avicenna, which, however, I have been unable to verify. A French physician, cited by the aforementioned Borellus, assures us that a servant of Henry IV spoke Greek while in a fever, although the question is, of course, how much Greek the physician himself understood, since Greek would otherwise mean as much to him as Spanish or Bohemian does to us. More significant is the testimony of the well-known Lamothe Levayer, who, in his works (Tom II, p. 657), has a letter of his own entitled: d’un homme, qui répondit étant endormi en toutes langues, où on l’interrogeoit, quoiqu’il ne les sçut pas. The man in question was to be found in Rouen, and was called Le fevre. In the Actis Naturae Curiosorum, there is a story of a woman who, during her pregnancy, writhed in ecstasies [in Ekstasen gerieth], in which she sang songs unknown to her and spoke in foreign tongues, and the aforementioned Borellus himself claims to have treated a woman who spoke in perfect Spanish throughout the entire course of an illness, though she had been ignorant of the language before and was again afterwards. Finally, a similar story from more recent times is well-known to several physicians, psychologists, and other trustworthy persons in Stuttgart, and is to be found in the generally, and correctly, esteemed work entitled Ueber die Entwicklungskrankheiten by Hopfengärtner.

In earlier times, considerable effort was made to explain these phenomena. They partly served as proof of the demonic origin of a number of diseases; for this reason, Erasmus ridiculed such stories in his Declamatio de laude medicinae (p. 542). Upon return from [such a condition], the ground for this was sought in the natural omniscience of the soul; Pythagoreans would cite them as proof of metempsychosis and reincarnation, deriving everything which transpired in them from a previous existence. However one may interpret these phenomena or explain them away, they at least serve to intimate something more innerly in language; for even if one restricts themselves to what is least likely to be scrubbed out in the examination of the available testimonies—there is still enough left remaining to prove that a source of language lies within human beings, which, like so much else hidden away within him, emerges more freely under certain circumstances and develops into a higher, more universal linguistic sensibility [Sprachsinn], as in the case of somnambulism it is not the special sense of vision [specielle Gesichtssinn], but a higher, more universal one whereby the presence of other things is felt. If there is, however, an inner ground of language, then, because this ground must be [the same] in all human beings, the possibility of a language universal according to its nature must also be conceded, one which everyone would speak of their own accord if they were placed in this inner ground, this centrum of all language, and which everyone would understand if this inner ground were stimulated or alive in them.

Few have thought about the problem of the first origin of language in all of its asperity, for otherwise the usual explanations would hardly have satisfied so many. For even if one would assume that human beings give names to things arbitrarily, how, then, did so many of them come to an agreement to refer to the same things with the same names? How could they have made this intention known? Through word and language, which would then themselves have to be explained first? Thus here, at the very least, something immediate and—to just say it outright—magical must be assumed, which, however, in the end, may just be something physical that was hitherto unrecognized. Just as the diversity of languages, which, already in the earliest ages of the world [früheste Weltalter] were found to be so wondrous that the oldest book in the world felt the need to give its own explanation for it; so too are the undeniable similarities between the farthest-flung languages, such as those between German, ancient Indian, and Persian on the one hand and Greek on the other, a problem far from being properly solved. One can, of course, explain much on the basis of ancestry or historical intercourse; but even here, there are no completely unmediated relationships, such as can only occur in an organic whole. I recall the similarity which has recently been found between several American dialects and the Slavic languages, doubly wonderful and significant, since the original American tribes [amerikanischen Urstämme], judging by Humboldt’s remarks, also display the closest similarity with the Slavic peoples in character, disposition, and spiritual properties.22 Ought we conclude from this a former connection between the two? Just as it is the same original granite that nature has produced at the foot of the European high-Alps and the valleys of the American Andes-Chain, albeit with some variation on the mixture of elements, one might well ask whether there are not entire peoples and homologous linguistic formations [homologe Sprachformationen] which, just as [homologous] mountain formations [Gebirgsformationen], arising independently from one another, might recur in the most diverse quadrants of the map [Weltgegenden].23 Such facts serve to prove that even in the individual languages, there is nothing accidental, that the greatest lawfulness prevailed in their very first origins.24 Once one looks upon the wondrous tree of languages [Wunderbaum der Sprachen], upon which each branch stands out for itself, impenetrable to the others, yet, according to the content or or matter of their concepts, are all more or less the same; once one looks upon this thousand-branched tree with more universal ideas; once one cognizes that which is physical in language, and traces and orders the facts of the history of peoples and languages in connection with, or at the very least by analogy with, the facts of geognostic history—then what admirable, even unbelievable, regularity and lawfulness will be revealed to us!

However, it is time to turn back from these digressions. The aim of this essay as a whole was to show that pasigraphy, if it would truly fulfill its concept, must presuppose a natural connection between word and thing. This natural connection led us to the concept of an objective [language] or nature-language [Natursprache], which would be the sole original language [Originalsprache], primordial language [Ursprache], and universal language [Universalsprache]. Whatever was to be said in favor of the reality of this nature-language from various sides was then mentioned. Accordingly, it has been shown that the efforts of pasigraphers either have a fairly common, yet not even really achievable purpose, or, if given higher intentions, lead to a concept one would not hesitate to consider mysterious and mystical, I can leave it to the academy to decide whether it considers the current endeavors in pasigraphy worthy of promotion in one respect or another.

c) As an intellectual exercise.

One must concede that Mr. Schmid is far removed from such far-ranging ideas, and since he does not deviate in any way from the universally recommended logical-psychological method, I propose, in conclusion, his pasigraphic exercises as variations on the erstwhile so-called intellectual exercises [Verstandesübungen], if they still take place under some other designation in in our schools, since a certain variety in these would be desirable in any case.

Incidentally, I ask that you please excuse the perhaps unusual form of my report. Lightness of thought is a beautiful thing, only one must not presume [to tackle with it] objects which drive us back into the abyss of human nature such as language—cet art léger, volage, démoniacle, as Montaigne’s expresses it so beautifully—for which the key has not yet been found. The question raised here concerning the natural connection between word and object is the topic of Plato’s Cratylus; even in later times, according to Aulus Gellius (Noct. Att. X, 4), Roman philosophers were still preoccupied with the question of the names of things were φύσει, vi et ratione naturae, or θέσει, positu fortuito. Even these philosophers only knew that there was a mimetic connection of words to nature, the only one still known to our modern philosophers. Pasigraphy would have merit enough if it gave rise to new inquiries into language, which, as far as the mysteriousness of its origin and existence, the wonders of its inner structure, its organic perfection, and its almost unforeseeable ramifications are concerned, is unrivaled in greatness by any object.

Munich, 6/8/1811.

See the BAdW website on Schelling’s role in founding the Akademie der Bildenden Künste (Academy of the Plastic Arts). For more on Schelling’s role in the academy in 1811, including his duties as secretary and his anonymous critique of their 1811 exhibition, see: Yahata, S. (2021). Schelling’s Activities in the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich. Academia Letters, Article 915. https://doi.org/10.20935/AL915.

Translated by Jason M. Wirth for Vol. 3 of the North American Schelling Society’s journal, Kabiri (2021): “On The Relationship of the Plastic Arts to Nature”

A new, historical-critical edition—translated and edited by Alexander Bilda, Jason M. Wirth, and David Farrell Krell—of On the Deities of Samothrace is being published through IUP in early 2025.

For a timeline of Schelling’s revisions of the Weltalter-project from its conception in 1810 through his last lecture delivered under the title System der Weltalter in 1833, see Aldo Lanfranconi’s Krisis. Eine Lektüre der ›Weltalter‹-Texte F. W. J. Schellings. (Frommann-Holzboog, 1992)

Schelling, In: On University Studies. Translated by E.S. Morgan, Edited with an introduction by Norbert Guterman. (Ohio University Press, 1966), 40.

Joshua Ramey and Daniel Whistler: “Schelling's later writing often turns to philology, precisely because language is one of the ways in which the depths become manifest as depths.” In: “The Physics of Sense: Bruno, Schelling, Deleuze.” Gilles Deleuze and Metaphysics, Edited by E. Kazarian et al (Lexington Books, 2014)

Whistler: “Second, [in the 1811 Bericht,] Schelling advocates understanding the history of language “in connection or at least in analogy to the geological”. This is key to my present purposes. Here, Schelling goes beyond his own initial comparison with mountain formations: language should not be merely thought of “in analogy” to geological phenomena, but—more than that—“in connection” with them. This connection goes beyond a merely regulative metaphorical relation to a determinative, ontological one. Schelling transcends his initial cautious separation of the linguistic from the geological, so as to discover their common ground. The geo-logical supercedes the ana-logical.” Following Iain Hamilton Grant’s interpretation of Schelling’s nature-philosophy as ‘transcendental geology,’ Whistler reads the 1809 Freiheitsschrift as an argument for the extension of the ‘geological model’ to ideal or spiritual formations in human history, as both geology and philology are historical sciences that reconstruct a history of form-determining catastrophes: “We are now in a position to understand the identity—and not just the similarity—of philology and geology which Schelling intimated in On University Studies. Moreover, we are now able to do as the 1811 Bericht advises: think words in connection with the geological. As we have seen, religion is nature recapitulated: there is no separation between the two; rather, an identity. In the same way, following the Schellingian notion of non-linear recapitulation, rocks and words are nature in different potencies. Both philology and geology attempt to uncover exactly the same ground.” In: “Language After Philosophy of Nature: Schelling's Geology of Divine Names.” After the Postsecular and the Postmodern: New Essays in Continental Philosophy of Religion. (Cambridge Scholars Press, 2010), 364-389.

Schelling, In: Ages of the World (second draft, 1813), Translated by Judith Norman. (University of Michigan Press, 1997), 113.

Schelling: “Therefore, everything known, in accord with its nature, is narrated. But the known is not here something lying about finished and at hand since the beginning. Rather, it is that which is always first emerging out of the interior through a process entirely specific to itself. The light of knowledge must rise through an internal cision and liberation before it can illuminate. What we call knowledge is only the striving toward anamnesis [Wiederbewubtwerden] and hence more of a striving toward knowledge than knowledge itself. For this reason, the name Philosophy had been bestowed upon it incontrovertibly by that great man of antiquity.” In: The Ages of the World (Fragment), from the handwritten remains. Third Version (c. 1815). Translated, with an Introduction, by Jason M. Wirth (SUNY Press, 2000), xxxvii.

See below: “I recall the similarity which has recently been found between several American dialects and the Slavic languages, doubly wonderful and significant, since the original American tribes [amerikanischen Urstämme], judging by Humboldt’s remarks, also display the closest similarity with the Slavic peoples in character, disposition, and spiritual properties. Ought we conclude from this a former connection between the two? Just as it is the same original granite that nature has produced at the foot of the European high-Alps and the valleys of the American Andes-Chain, albeit with some variation on the mixture of elements, one might well ask whether there are not entire peoples and homologous linguistic formations [homologe Sprachformationen] which, just as [homologous] mountain formations [Gebirgsformationen], arising independently from one another, might recur in the most diverse quadrants of the map [Weltgegenden]. Such facts serve to prove that even in the individual languages, there is nothing accidental, that the greatest lawfulness prevailed in their very first origins.”

Schelling: “Not only human events but the history of nature has its monuments and one can surely say that they do not abandon on their wide path of creation any stages without leaving behind something to indicate them. These monuments of nature, for the most part, lie there in the open, and are explored in manifold ways and are, in part, actually deciphered. Yet they do not speak to us but remain dead unless this succession of actions and productions has become internal to human beings. Hence, everything remains incomprehensible to human beings until it has become internal to them, that is, until it has been led back to that which is innermost in their being and to that which to them is, so to speak, the living witness of all truth.” In: The Ages of the World (Fragment), from the handwritten remains. Third Version (c. 1815). Translated, with an Introduction, by Jason M. Wirth (SUNY Press, 2000), xxxvii.

Schelling, In: Ages of the World (second draft, 1813). Translated by Judith Norman. (University of Michigan Press, 1997), 121-122.

Schelling says of the “genesis of mythological representations” in the final lecture (Lecture 6) of the Monotheismus lecture sequence (~1828/29-1845/46): “Further, although they are the creations of human consciousness, they nevertheless are not (…) its products insofar as it is human consciousness, but on the contrary, insofar as the principle of human consciousness came out of the relation in which it alone is the ground of human consciousness, namely from the relation of rest, of pure essentiality or potentiality. They are products of the human consciousness that has come out of its ground, and which is only brought back through this process into the relation where it actually is human consciousness. To this extent, mythological representations can or must be considered the products of a relatively pre-human consciousness—namely as products of human consciousness (as well as of substantial consciousness) inasmuch as it has been restored to its pre-human relation. In the sense we have defined, one can compare mythological representations to the formations and productions of pre-human times of the earth, as Alexander von Humboldt has done—I will not venture to determine in which sense exactly (I doubt he wanted to allude to the monstrosity of both). I cannot help but remark here how fundamentally misleading it is to have mythology personify objects in actual nature. The ideas of mythology go beyond nature and the present state of nature. In the process that produced mythology, human consciousness finds itself again at the time of the struggle that had found its goal with the advent of human consciousness, in the creation of man. Mythological representations arise directly from the fact that the past that is already vanquished [besiegte] in external nature re-appears in consciousness, that the principle that is already subjugated in nature again takes hold of consciousness itself. Far from being, in the production of mythological representations, in nature, man is rather outside the latter, in some sense removed [entrückt] from nature, and fallen prey to a force that, in relation to the existing nature (which has come to a standstill, come to rest), or in comparison with it, must be called a supernatural or extra-natural force.” Translated by Hadi Fakhoury, In: “F.W.J. Schelling's Later Philosophy of Religion: A Study and Translation of ‘Der Monotheismus.’” (2020), 283.

Schelling, In: Historical-critical Introduction to the Philosophy of Mythology. Translated by Mason Richey and Markus Zisselsberger, with a Foreword by Jason M. Wirth. (SUNY Press, 2007), 150.

Schelling: “It is desirable in itself for one who speaks about the first beginnings as an initiate to connect to something or other venerable from time immemorial, to some kind of higher, attested tradition upon which human thought rests. Even Plato himself, at the highest points and peaks of his remarks, likes to call on either a word inherited from antiquity or a holy adage. The reader or listener is thereby retrieved from the detrimental opinion that the author had wanted to spin everything out of his or her own head and only communicate a self-ascertained wisdom. The effort and tension this opinion always arouses turns into the calm mood that a person always feels when they know that they are on solid ground and which is so advantageous to research. Such a connection is doubly desirable to the one who does not want to push a new opinion but who wants to assert again truth that existed long ago, even if it was concealed, and who wants to do this in times that really have lost all stable concepts. Where could I more likely find this tradition than in the imperturbable documents that eternally rest in themselves and that alone contain a world history and a human history that goes from the beginning to the end? These may serve as an explanation if the sayings of those holy books are remembered hitherto from time to time and if this in turn will occur more often. For if the author had just as often referred to the Orphic fragments or the Books of Zend or Indian scriptures, then this could perhaps have counted as scholarly adornment and appear much less strange than the reference to these Scriptures whose consummate explanation in view of its language, history, and teaching would have to combine all of the science and erudition of the world. For no one will want to claim that the contemporary conceptual tools have exhausted the riches of the Scriptures. And no one will want to deny that the system that would explain all of the sayings and bring them into consummate harmony has not yet been found. A lot of the most difficult passages to understand must either be left in darkness or neglected. Hence, one finds the most outstanding points of teaching in our systems, but they are described rigidly and dogmatically, without the inner link, the transitions, the mediating terms that alone would have made them into a comprehensible whole that no longer demanded blind faith but would get the free assent of the spirit as well as the heart. In a word, the interior (esoteric) system, whose consecration the teachers should especially have, is lacking. But what particularly hinders teachers from reaching this whole is the almost improper disregard and neglect of the Old Testament in which they (not to speak of those who give it up altogether) only hold as essential what is repeated in the New Testament. (...) [O]nly the singular lightning flashes that strike from the clouds of the Old Testament illuminate the darkness of primordial times, the first and the oldest relationships with the divine essence itself.” In: The Ages of the World (Fragment), from the handwritten remains. Third Version (c. 1815) Translated, with an Introduction, by Jason M. Wirth (SUNY Press, 2000), 50-51.

Schelling: “Linguists and philologists least of all should have confidence in the conclusion that poetry and philosophy, because they are found in mythology, have contributed toward its emergence into being. In the formation of the oldest languages a wealth of philosophy can be discovered. However, was it therefore actual philosophy by virtue of which these languages had the ability, in the nomenclatures of often even the most abstract concepts, to preserve their original meaning that had become foreign to the later consciousness? What is more abstract than the meaning of the copula in a judgment? What is more abstract than the concept of the pure subject, which appears to be nothing; for what it is we only experience via the statement, and yet even without the attribute it cannot be nothing: for what is it then? When we articulate it, we say of it: it is this or that—for example a person is healthy or sick, a body dark or light; but what then is it, before we express this? Evidently, only that this—for example, healthy or sick—is that which is a capacity to be. Thus the general concept of the subject is to be pure capacity to be. Now, how strange that in Arabic the word “is” is expressed by a word that is not merely homonymous with our word “can,” “is able to,” but rather is inarguably identical in that, contrary to the analogue to all other languages, it is not followed by the nominative of the predicate, but rather by the accusative, like “can,” “to have the capacity for,” “to be able to” in German (for example: “to have the ability” for a language), or posse in Latin (not to mention the others). Was it philosophy that spun a web of scientific concepts into the various and, at first glance, most heterogenous meanings of this same verb, a web whose context and coherence philosophy has trouble finding again? Arabic in particular has verbs rich in completely disparate meanings. What one customarily says, that originally separate words—which the later pronunciation no longer differentiated—are here coalesced, may be believable in some cases; but it would only be acceptable when all means of uncovering an internal interrelationship were applied without success. But it indeed occurs that other investigations unexpectedly put us in a position where between apparently irreconcilable meanings, in this ostensible confusion, a philosophical coherence and interrelationship, a true system of concepts, reveals itself: concepts whose sound coherence and interconnection lie not on the surface but rather disclose themselves only to deeper scientific interventions.” In: Historical-critical Introduction to the Philosophy of Mythology. Translated by Mason Richey and Markus Zisselsberger, with a Foreword by Jason M. Wirth. (SUNY Press, 2007), 39. Italics in original.

“Bericht über den pasigraphischen Versuch des Professor Schmid in Dillingen.” (SW VIII.439-454.)

“not not equivalent to the concepts themselves, but are in actuality mere signs”: [nicht Aequivalente der Begriffe selbst, sondern wirklich bloße Zeichen]

[Die Stelle, die ein Begriff in der Reihe erhält, wird bloß darnach bestimmt, ob er unter einen gewissen andern Begriff subsumirt werden kann, nicht aber darnach, daß er unter ihn subsumirt werden muß.]

Steven P. Lyndon: “The sound figures were an oscillating metal plate that produced two-dimensional shapes in the sand when musical notes were played through it. Ernst Chladni, the German acoustician who discovered the phenomenon in 1789, exhibited it at public demonstrations around Europe. But despite the support of Napoleon himself, the sound figures could not be explained mathematically. So in these sound figures, F. W. J. Schelling found confirmation of dynamic physics and posited a Signatura rerum. August Schlegel built this claim into his lectures on art history and aesthetics, and Clemens Brentano celebrated the experiment in his poetry. Thus did philosophy and literature express the full significance of an insoluble problem in mechanical physics, illuminating the reciprocity of science and culture at the turn of the eighteenth century.” In: Lydon, Steven P. 2018. “Signatura Rerum: Chladni’s Sound Figures in Schelling, August Schlegel, and Brentano.” The Germanic Review: Literature, Culture, Theory 93 (4): 334–50. doi:10.1080/00168890.2018.1509051.

Skipping sub-sections titled “Practical applicability.”, “Testing through experiments.”, and “Further Utilizability. a) With regard to the philosophy of language.”

[Ich erinnere an die Ähnlichkeit, die neuerdings zwischen mehreren amerikanischen Dialekten und den slavischen Sprachen gefunden worden, doppelt wunderbar und bedeutend, da die amerikanischen Urstämme, nach Humboldts Bemerkungen zu schließen, auch in Charakter, Gemüthsart und geistigen Eigenschaften die nächste Ähnlichkeit mit den slavischen Völkern zeigen.]

[Wie es vielmehr ein gleich ursprünglicher Granit ist, den die Natur am Fuß der europäischen Hochalpen und in den Thälern der amerikanischen Andes-Kette, wenn auch mit einiger Variation der Gemengtheile, producirt hat, so möchte man fragen, ob es nicht ganze Völker und homologe Sprachformationen gebe, wie es Gebirgsformationen gibt, die sich in ganz verschiedenen Weltgegenden unabhängig voneinander wiederholen können.]

Re: ‘Weltgegenden’: “We learn from Christian Wolff's Mathematisches Lexicon that a Gegend (Latin plaga) is the intersection of an azimuth with the horizon: "At sea, Gegenden are determined with a compass." In "What is Orientation in Thinking," Kant says "We divide the horizon into four [Weltgegenden],” that is, main [or cardinal] compass points, or quarters (8.134).” In: George, Rolf, and Paul Rusnock. Review of Review Essays: Snails Rolled Up Contrary to All Sense, by James Van Cleve and Robert E. Frederick. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 54, no. 2 (1994): 459–66. https://doi.org/10.2307/2108507.

“the greatest lawfulness”: [die größte Gesetzmäßigkeit]