Translation: Horkheimer's Lectures on The Radical Enlightenment (1927)

From his "Introduction to the History of Modern Philosophy" course.

Contents.

Translator’s note.

Introductory Remark.

XIII. The Enlightenment.

General Characteristics of the Epoch.

Sensualistic Epistemology (Erkenntnistheorie).

Morality of Self-love (Selbstliebe).

Critical Historiography.

Role of Education.

Physical Materialism.

Rousseau.

Utopian Socialism.

Condorcet.

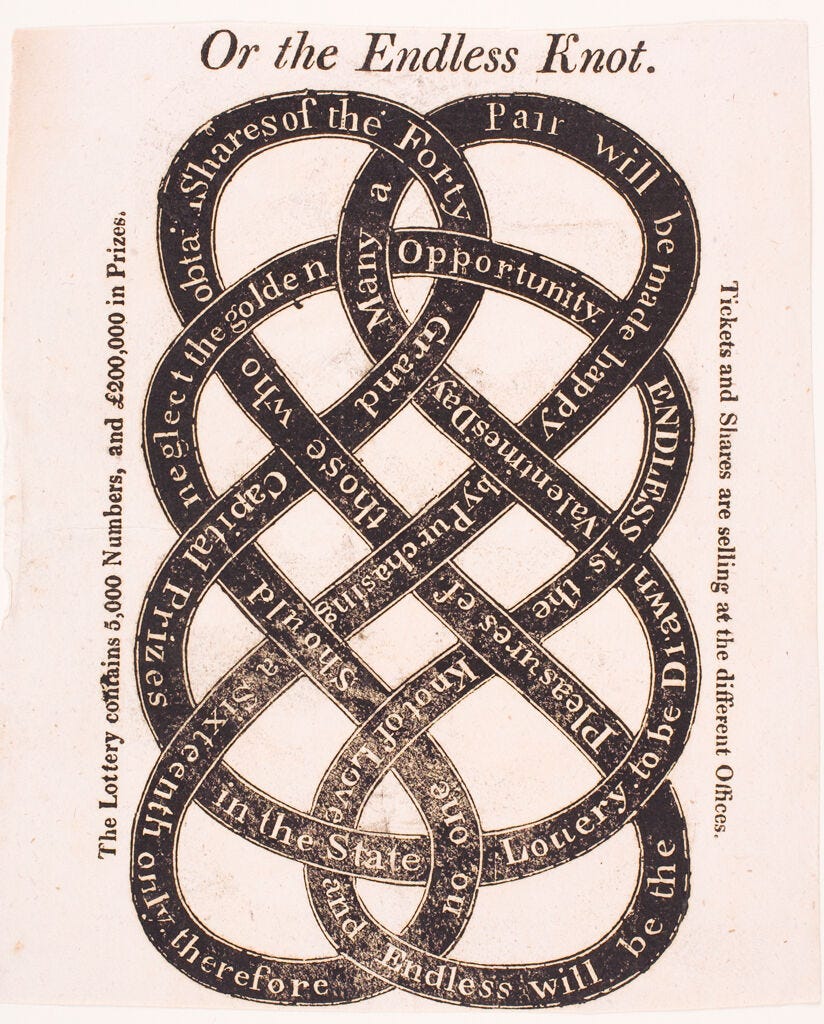

Mandeville.

Ferguson.

The Difference between the Enlightenment and Positivism.

Translator’s note.

Below is a translation of the unit devoted to the philosophy of the Enlightenment from Max Horkheimer’s 1927 course, “Introduction to the History of Modern Philosophy,” posthumously published in the 9th volume of the Gesammelte Schriften (1987).1 Where possible, I’ve quoted from standard or accessible English translations of the authors Horkheimer cites. Unless indicated otherwise, translations of the excerpts are my own (many of them from Horkheimer’s own occasionally creative translations of the French source materials into German for his lectures). I’ve recently posted translations of several excerpts from Horkheimer’s introductory lectures to his introductory-level philosophy courses of 1926 and 1927 (on the histories of contemporary and modern philosophy, respectively) in which Horkheimer reflects on the method of the history of philosophy and argues for the possibility of a ‘scientific’ (Marxian ‘materialist theory of history’) approach to the subject:

Introductory Remark.

In lieu of an introduction that engages with the relevant secondary literature, I want to mention three reasons why this material seemed worth translating. The first: while Horkheimer declares himself for the worldly raison of the Philosoph over the reine Vernunft of the critical Aufklärer in his debut publication, “Beginnings of the Bourgeois Philosophy of History” (1930),2 his references to the French enlighteners in his published and translated works of the 1930s are few and far between compared to his constant, critical engagement with Kant throughout the formative period of critical theory. He will even conclude the entire lecture series by leveraging Helvétius, by way of Marx’s Theses on Feuerbach, into a critical recovery of Kant for decidedly anti-Kantian ends:

In the Critique of the Power of Judgment—at least, in the section on aesthetics—an attempt is made to establish the absolute principles of art through a consideration of the formal elements in our aesthetic comportment, the “universal validity” of such principles for all rational beings in all times, as was done for science and morality. And yet, to date, there has never been an absolute science nor an absolute ethics nor an absolute art; Kant knew nothing of historically conditioned validity for human beings of a determinate time and determinate social classes. Instead of undertaking investigations such as these, Kant dedicated his immense philosophical capacity to the attempt to rescue metaphysics. That there was more to the work of this ingenious man than first meets the eye, and more than he perhaps knew himself, was proven in the later development of idealist philosophy, which, despite Hegel’s adherence to an idealistic metaphysics, led to methods and results which undermined its basis. By way of conclusion, one important step beyond the old materialism can be mentioned. It lies in the fact that, until now, “the subject matter, actuality, had only been grasped in the form of the object or intuition; but not as human, sensuous activity, praxis—not subjectively.” Kant is the stimulus for the fact that “the active side, in opposition to materialism, was developed by idealism—but only abstractly, since, of course, idealism does not know actual, sensuous activity as such.”3 In any case, Kant is the first to consistently grasp cognition not merely as reproduction or reflection, but as process, as production, though this production is still grasped as the production of an abstract subject of cognition and not yet as a function “en société que suppose toujours la réunion des hommes,” as Helvétius already formulated it.4

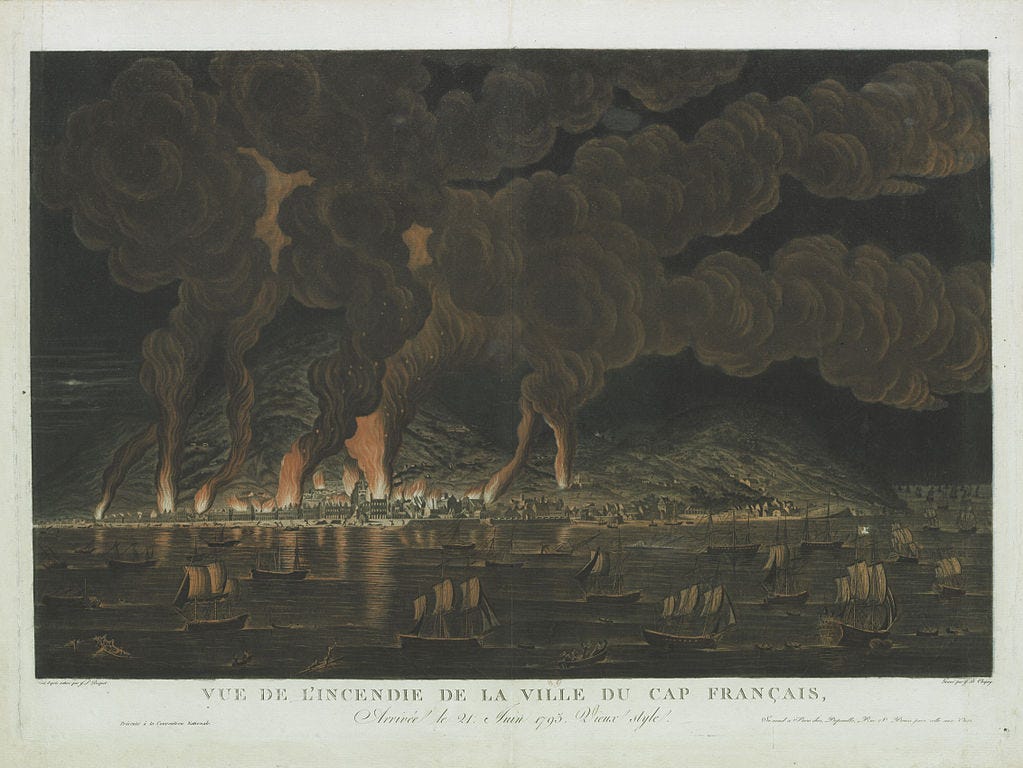

This brings us to the second reason: to my knowledge, nowhere is Horkheimer more unequivocal that the living legacy of the radical French Enlightenment is in scientific, revolutionary socialism—though, much like Marx himself,5 Horkheimer thinks this is less because the socialist critic longs for the imaginary reconciliations of utopian socialists like Morelly than because the socialist critic inherits the acidic social analyses of enlightened immoralists like Mandeville. The problem of morality relates to the third and final reason: with the exception of “Egoism and Freedom Movements” (1936),6 these lectures are perhaps the best dramatization—particularly through the figure of Rousseau, the thinker Horkheimer seems to identify with and find repulsive in equal measure—of Horkheimer’s conviction through the 1930s (and, arguably, the 1940s) that the rationality of so-called “bourgeois values” is proven by the fact that ‘the sons of rich parents,’ as Horkheimer and Adorno liked to call themselves, would see the world arranged for their privilege burn before they would allow those values “to become as much abandoned by truth as the “liberté, égalité, fraternité” posted over the prisons of the French Republic.”7 In an unpublished fragment written nearly a decade after the lectures below, “Bourgeois World” (ca. 1936), Horkheimer shows his hand:

The late bourgeois [die späten Bürger] know that their ideals will either, and only, be realized through proletarian revolution, and within a socialist order, or will never be realized at all. If there can be any theoretical knowledge in the field of human, and social, life; if anything whatsoever has been manifestly proven by history—then it is this insight. … [T]hose who carry the bourgeois ideals not so much in their words but in their hearts find as little community with those miserable liberal and democratic reformers as they do with fascists themselves, and, conversely, both of these groups know very well that their enemy is simply uncompromising knowledge, and the attitude which corresponds to it.

In the lectures from his “Introduction to the History of Modern Philosophy” themselves, this thesis—that the radical enlightenment is either scientific, revolutionary socialism or it is nothing—is clearest in lecture five, innocuously delivered under the heading of “[The] Role of Education,” where Horkheimer writes of Helvétius:

He speaks of the relation between two classes, the rich and the poor, as he expresses it, and that the distinction in the standard of living between the two is so enormous, and that work for the poor is so oppressive and hopeless, so joyless, that there can no longer be any talk of a union of private and general interests. He predicts this society’s collapse. Here is the point where the connection between these doctrines of the enlightenment and latter-day socialism becomes clearly visible. It is self-evident that the demand for the organization of human society according to the principle of adaptation to the natural interests of the greatest possible number of its members, the demand for the most rational configuration of social relations possible—this could not even be laid to rest even after the French Revolution, after the expansion of the economic order of free competition. The legacy of the social critique of the enlightenment, which originally referred to conditions under absolutism, was taken over after the revolution by the socialist critique directed against the bourgeois order…

My hope is that this translation of Horkheimer’s lecture sequence on ‘The Enlightenment,’ in which the zenith of bourgeois thought is presented as the immediate prehistory of the radical and total socialist criticism of bourgeois society itself, will serve as a provocation in the ongoing debates about Horkheimer and Adorno’s concept of the enlightenment.

XIII. The Enlightenment.

[1.] General Characteristics of the Epoch.

Hardly any period poses more difficulties to presentation than the age of Enlightenment, the philosophical condemnation of which is today so unanimous. The enlightenment has, in all countries and around the entire world, been supplanted by a now-dominant romantic counter-current, and it has ensured that a totally distorted conception of enlightenment philosophy has gained currency. None of the many available textbooks on the history of philosophy are missing a chapter on the enlightenment, and yet it is nevertheless true that not one of them contains a usable presentation of its philosophy. Chief among the prejudices which inhibit this is the false opinion that the three great countries of West- and Central-Europe—England, France, and Germany—each engendered a philosophy of the same kind at the same time, a philosophy which agreed on all essentials and pursued the same intentions. It is easy enough to come to such a conclusion if you approach the matter with the customary “problemgeschichtlichen” (“problem-historical”) methods. If one asks which theories were held to be valid with respect to which objects in epistemology, moral philosophy, pedagogy, and political philosophy, they would surely find a number of things about which the philosophers who lived in the above-mentioned countries at the time could agree. This is all the less surprising given that these philosophers had relatively close relationships with one another. Voltaire had not only been to England as a young man, but also lived for a long time at Prussian court, where he discussed Wolff’s philosophy with Frederick II and Maupertius, director of the Royal Academy, and alongside another Frenchman seated at the same table, La Mettrie. Nevertheless, the assertion that the enlightenment was a unified movement across Europe is a legend.

If the question is not posed in problem-historical, but historical terms, it soon becomes clear that the French philosophy of the enlightenment fulfilled a different social function in principle compared to other philosophies of its time in other countries. The philosophy of the French enlightenment was the revolutionary critique of existing conditions, invested with the most relevant of interests in the political movement directed against the existing state of affairs in France; and this movement in turn brandished this philosophy as one of its sharpest weapons—indeed, one might even say as its most important weapon—in the course of its struggles. Epistemological, moral, and pedagogical motives were totally and exclusively subordinate to the organizing political interests among the French, and these motives were even handled by this philosophy with an obvious license in manner. “Philosoph” was, in Paris in the middle of the eighteenth century, a name whose bearers had a determinate social-critical and political conviction. They had their conspiratorial methods, their secret goals and tactics. They were connected with one another like members of an illegal political group, and when one of them was persecuted, when he was in danger of being ruined for his convictions, the others would portray him with a veneer of harmlessness in their writings, both for his sake and for the sake of their cause. Their stance towards religious and political questions (which were essentially identical at that time) were dependent, therefore, on their situation, and the greatest philosophers among them were entirely conscious of this fact. When their books were published abroad, or after their death, they were unambiguously opposed to and irreconcilable with Catholic absolutism; when they were published in France and under the author’s own name, harmless and conciliatory.

The French enlightenment consisted of the attempt, by means of modern science, to undermine and destroy all ideological supports for the regime which existed at the time. These pillars were essentially religious, ecclesiastical intuitions—and so the motto of the enlighteners became the cry: “Écrasez l'infâme!” It may sometimes seem as if their struggle was only directed against the church, but not the institutions of the existing order; in their works, the enlighteners would appeal to the king as benevolent sovereign, act out their devotion to some ecclesiastical authority in court, secure the protection and patronage of some high noble lord—anyone who judges the spirit of this philosophy by such external signs would completely misunderstand the consciousness of its greatest philosophers. In fact, they would end up drawing some entirely agreeable conclusions: namely, they would discover that Voltaire was devoted not only to the King but to the Church as well. After all, he dedicated his Mahomet with the most respectful of letters, and even received a benevolent and gracious answer in return. But just as Voltaire’s dedication was merely supposed to make it possible for his highly irreligious Mahomet to be performed in France, by obtaining a coveted papal approval in reply, his effort to secure courtly protection and patronage was nothing other than pure tactics. You only need recall how Voltaire conducted himself in the court of the Prussian King after befriending him.

After a number of close encounters, there was an incident which made Voltaire’s continued residence in Prussia intolerable: the fury of the King after he was coaxed into granting permission for the publication of a piece of writing he never would have allowed to go to print under normal circumstances. Voltaire never held back from using such means when he realized they could no longer arrive at any agreement about the matter. It was not the favor of the King, but the possibility of continuing his work towards his own goals through his relationship with the King which, for Voltaire, furnished the basis for their friendship. These goals had reached their practical end-point. As is well-known, Voltaire only maintained the relationship as long as he believed it might further his cause, and it is thus to Frederick’s great distinction that even after their break, he placed great importance on a reconciliation which would not be broken for the rest of his life. It cannot, however, be said that Voltaire’s relationship to Frederick, or any other sovereign for that matter, was inflected by a feeling of sincere admiration for sheer Kingly splendor, as one could say about Goethe, for instance.

The French enlightenment was pitilessly anti-authoritarian towards existing powers. For this reason, it cannot be understood as identical with the philosophies of its English and German contemporaries—however often it may employ theoretical doctrines which are very similar to those their contemporaries recognize. However often or emphatically Diderot might present Christian Wolff as an authority on logic, or Voltaire sing the praises of the English, in the eighteenth century English philosophy no longer had a revolutionary function; its representatives—Berkeley and Hume—consciously strove for reconciliation with that which exists [Bestehenden], a status quo to which even a man like Shaftesbury is completely resigned, for all of its ‘improvements’ and other changes. In Germany, however, it wasn’t until the middle of the nineteenth century that social relations would take on a shape which could be compared in a political sense to the state of affairs that had prevailed in England and France a century or so prior; the writers from Leibniz to Kant have completely different, and much more purely speculative, interests than did their French contemporaries.

However, Lessing, student of Pierre Bayle and Voltaire, was even more radical and irreconcilable towards all darkness and obscurity than Voltaire himself; indeed, he was even more unambiguous in his proceedings against the absolutist courts than Voltaire, whom Lessing simultaneously hated and revered. Even the latter’s hatred for the Frenchman was always, and fundamentally, the aversion of a more consistent writer of the bourgeoisie towards the courtly elements that lingered in Voltaire’s work. This singular, great man stood alone in Germany, at one with all enlightened tendencies of his time but without finding any real resonance, any like-minded peers, any following. As it was for Lessing in Germany, so it was, in a certain sense, similar for Mandeville in England.

Lessing (1729-1781) was previously mentioned in connection with the French enlightenment. Even though he stands in contradiction to its representatives on several key points, his name cannot be mentioned in the same breath as the German Popularphilosophen [viz., Wolff, Mendelssohn, Jacobi]. Though he may have had something like natural religion as his goal, the clarity and sharpness of his critique, which was by no means restricted to aesthetics, elevates him far above the insight of his peers. The goal of establishing of a natural theology, i.e. the ultimate definition of demonstrable religious propositions which are thereby supposed to constitute absolute truths, cannot be considered essential for a thinker whose fundamental philosophical proposition is as follows: “If God were to hold all Truth concealed in his right hand, and in his left only the steady and diligent drive for Truth, albeit with the proviso that I would always and forever err in the process, and to offer me the choice, I would with all humility take the left hand, and say: Father, I will take this one—the pure Truth is for You alone.”8

Therefore, though there was no “enlightenment” which stretched across Western and Central Europe, there was a political movement among the French bourgeoisie in which a series of brilliant philosophical and artistic writers, by means of knowledge,9 dismantled the remnants of the feudal form of life and opened the path which led to the great revolution. That the philosophy of this movement has on a number of points transcended its bourgeois impulses and acquired insights which strike the narrowly bourgeois ideology that followed it as intolerable—this is attested to not only by the fact that the revolution projected goals far beyond that which it could attain, but also in the bitterness with which a man like Sombart speaks of the “Aufkläricht” (“shallow-/pseudo-Enlightenment”) and even calls, at so late an hour, for Helvétius to be whipped. —Of course, we cannot claim that all of the enlighteners, such as Voltaire, had revolution in mind.

On this matter, they diverge widely. It would be completely false to try to determine the objective meaning of their philosophy on the basis of their personal statements about possible political reconfigurations. Rather, the social significance of the enlightenment lies in its ruthless critique not only of the older, theological mode of thinking and all of its metaphysical echoes, but also of all that exists, above all the existing church and judiciary. However much Voltaire may have personally known how to appreciate the enjoyments and the luxuries, the arts and the splendors of the ancien régime, and however true it may be that he—had he foreseen the political transformation it would entail—would have despised the revolution, it is nevertheless true that in the face of his philosophy, which was among the most powerful midwives of the bourgeois order, not a single support of the ancien régime could remain standing. Furthermore, his supposed personal predilection for the ancien régime, his anti-revolutionary, aristocratic mood—all of this has been greatly exaggerated. When the revolution wanted to celebrate the anniversary of Voltaire’s death in 1791, it did not need too long to find in his works verses so unambiguous they might be sung for the occasion:

Peuple, éveille-toi, romps tes fers,

Remonte à ta grandeur première,

Comme un jour Dieu du haut des airs

Rappellera les morts à la lumière

Du sein de la poussière,

Et ranimera l'univers.

Peuple, éveille-toi, romps tes fers,

La liberté t'appelle;

Tu naquis pour elle;

Reprends tes concerts.

Peuple, éveille-toi, romps tes fers!10

Therefore we should not follow the prevailing error and speak of the enlightenment as some simultaneous spiritual mood on an international level, but solely in the spirit of the philosophy that corresponded to the situation in France right up to the outbreak of the Revolution. But this philosophy was shaped by so many important thinkers that it would be quite impossible for us to discuss each of them here. Instead, we will attempt to develop a general characterization and use it as an opportunity to name only some of the most important of the enlighteners and say something about their particular positions in this movement.

The theoretical philosophy or epistemology of the French enlightenment is contained in Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding. This work was considered to be thoroughly competent in all of the relevant epistemological disputes and questions of its day, and so it would be inappropriate to discuss the individual divergences in opinion about it here. At the end of his great work, A Treatise on Man, Helvétius himself provides a short survey of Locke’s epistemological views and concludes: “Such are the facts upon which I have anchored my work. I present it to the public in the confidence that the analogy between my fundamental principles and Locke’s guarantees me of their truth.”11 In response to the question of which among Locke’s theoretical doctrines in particular the enlightenment would adopt as foundations for its own philosophy, there is a precise answer that can be given: the rejection of innate ideas; the theory according to which all of our simplest ideas, along with the whole and original material of our knowledge, stems from experience; the fact that language is a mere means, and a highly imperfect one at that, for the description of things; the fact that there need not be anything like an autonomous and immaterial soul, but that matter itself might very well be the subject of all our thoughts. These are the basic theoretical principles which recur again and again through the writings of the enlighteners—in Voltaire, Helvétius, d’Holbach.

On the foundation of these basic principles, it is already possible for us to recognize and articulate the most important motive of this philosophy as a whole: namely, the principle that human knowledge is sufficient in all areas without the need for supernatural aid or illumination; that human knowledge is the intellectual processing of the experience which flows into us through the senses. This philosophy involves the rejection of every kind of transcendence, other-worldliness, divine inspiration and dispensation. We learn about all things through our senses, and science establishes the relationships between them and the regularities to which they are subject. Even the process of knowledge is purely a natural one, something which takes place in us as natural beings given the relationships we have with natural things and one another. As such, however, knowledge is the indispensable condition for any change or betterment of our state of affairs. We may only act as human beings on the grounds of our knowledge. The object and the goal of all activity is neither the heavens above us nor what lies deep within us, but the actual relations which make up our world. Thus, ignorance ranks among the greatest of evils in society, and its elimination through the proliferation of knowledge [Wissens] or “enlightenment” is in all places the precondition of happiness. “Knowledge of the truth is always useful,” writes Helvétius; “all truths are necessary and useful to men; all error is harmful to them,” Mirabeau says in the famous Lettres de Cachet, for “ignorance has made and will forever make tyrants and slaves.”

Ignorance cannot be eliminated by what is revealed or illuminated in religion, nor by devotion to God, nor by any vision or similar rapture, but solely by learning through the experience of nature and society. There are no objects of knowledge except those which are natural, and no means of knowing them except by experience, as Locke already described. The innate and ultimate concepts of the rationalists, on the basis of which they would have us draw all of our conclusions, still have too much of the odor of “revelation” and “natural light” about them for the enlightenment not to disown them. Yet, the enlighteners speak everywhere of reason—doesn’t such discourse have a ring of Descartes, Leibniz, and Wolff to it? Aren’t the enlighteners themselves ‘rationalists’ just as much as the metaphysicians they so fiercely struggled? —One need only flip open the nearest textbook on the history of philosophy to see, alongside all of the other accusations, the charge of ‘rationalism’ leveled against them. But such a view rests largely on ignorance about what the word “raison” meant to a Helvétius: nothing like what it meant to the Germans, nothing like what we have become accustomed to understand by the word after Kant and the post-Kantians.

We immediately think of a self-acting faculty which spontaneously produces knowledge within and from itself, by its own concepts; we think of a metaphysical centrum, the res cogitans which, by virtue of its self-acting, is endowed with autonomous power. None of this, however, is to be understood under “raison.” Its contrary in French is “tort,” which means unjust [Unrecht], incorrect [unrichtig]. Reason is, for the enlightenment, nothing but right thinking [richtiges Denken], as opposed to the wrong, as opposed to error. One is ‘rational’ if they make the correct use of their experiences, if they pass practicable judgments on the ground of their experiences, if they perform purposeful actions. If by “rationalism,” one understands merely the opposite of those intuitions according to which we ought to allow ourselves to be driven by “elementary” forces and act without reflection, then the enlightenment is certainly opposed to this same irrationalism that rationalism is. If, however, one uses this expression—as has been done until this point—in reference to the philosophy opposed to empiricism, then the enlightenment was certainly not rationalistic; for it fought and rejected any thinking which would presume to move independently of experience.

[2.] Sensualistic Epistemology (Erkenntnistheorie).

The Frenchman who spread and popularized Locke’s theory throughout his country was Etienne Bonnot de Condillac (1715-1780). None emphasized more strongly than he that it is impossible to gain any new knowledge by descending from the heights of presupposed fundamental principles and general concepts down to the level of individual facts. Rather, everything general is always and only an abbreviated expression, a means acquired through the artifice of abstraction, to orient ourselves amidst an abundance of details. It is wrong to seek Condillac’s preeminent achievement in his polemic against innate ideas. Certainly, in the Essai sur l'origine des connaissances humaines (1746) and the Traité des sensations (1754) he wrote brilliantly in opposition to this doctrine. But thanks to his English master, the perversity of this doctrine appeared so self-evident to him that it was not, fundamentally, a serious topic for discussion. What was more important to him was contesting the spontaneity and activity of the soul, or of consciousness, in a much more radical manner than Locke himself had. He abolished the separation between sensation as the passive receptivity to sense-impressions and reflection as the additional processing of these sense-impressions. This dualism is not justified. Our conscious life cannot be understood, as Kant later conceived it, as the switchboard operator for given representations from an active center. This would still mean there is yet something of an independent and autonomous spirit which, though it does not, as the rationalists imagined, produce the content of knowledge, is at the very least supposed to form and order the material fed to it by the senses according to its own, thing-independent principles. Such a conception would have left intact the same spirit Gassendi mocked, supposed to be independent of matter, with its own functions of concept- and judgment-formation to be introduced from above, so to speak, to the conditioned. This, however, could only be abhorrent to such a materialistic-thinking student of Locke’s. There is no independent spirit, no self-acting, personal center, some spiritus in the middle of the world, which each human being carries around with them, as it were, and to which one might attribute materially unconditioned activities. Therefore, Condillac dissolves the strict separation between ideas of sensation and reflection. What we call ‘concepts’ and ‘judgments’ are, in truth, nothing but sensations, or rather derivatives of sensations, derivative kinds of sensation which necessarily arise whenever a number of sensations are present.

What is memory other than a sensation which refers to the past; what is a concept other than a relatively indeterminate representation contained within a great many other representations; what is a judgment other than a certain kind of relationship which necessarily arises wherever a number of sensations are present at the same time? Concepts are abstract representations, judgments are relationships of equivalence or distinction between a number of representations. What were once considered products of the activity of the spirit are nothing other than relationships which are established wherever many sensations come together. All of these relationships are necessarily conditioned through experience, secondary functions of the influx of sensations through the senses, derived from experience, brought about by it, originally and completely acquired through it, and in no way issue as emanations from an inner, purely spiritual center.

The method by which Condillac seeks to make his view clear in the Traité des sensations is well-known. He employs the fiction of a marble statue into which all manner of sensations are introduced one after the other. We are meant to consider this marble statue as a living human being, one whose soul is still devoid of all representations. Because he is surrounded by a marble shell which does not permit him to use his own sense-organs without action on our part, it is possible for us to introduce certain impressions to him and shut him off from others. Thus Condillac performs the thought experiment in which the statue is opened up to olfactory impressions and investigates the states of consciousness which necessarily follow such impressions. He thus shows this one kind of impression is sufficient for generating what we are accustomed to calling the operations of the understanding [Verstandesoperationen], to condition the attention, memory, imagination, concepts, and judgments of the statue. Pleasure and displeasure [Lust und Unlust] arise from this as well. Still, it’s not as if all these experiences were anything but sensations: to the contrary, these experiences consist of nothing but derivatives of the influx of materials, forms and relationships derived from sensations. In time, the statue’s other senses are opened; lastly, its sense of touch. In a consistent advancement of the Lockean train of thought, Condillac says that it is only with the sense of touch that we experience a feeling of resistance, the impression of solidity and, therefore, the conviction of the reality of the outside world. Even ethical concepts and judgments are necessarily generated on the ground of sense-impressions, just as are aesthetic ones. The representations which are accompanied by pleasure receive predicates such as “good” and “beautiful.”

In later writings, especially the Logic and The Language of Calculus, Condillac extended the sensualistic theory of knowledge and applied it to a wide variety of epistemological problems. But what does this uniquely French expansion of Locke’s theoretical philosophy have to do with the enlightenment? Why has this doctrine that the ego of every human being is nothing but the “collection des sensations qu'il éprouve, et de celles que la mémoire lui rapelle,” that is, the collection and function of impressions which flow into it—why has this doctrine had such an enthusiastic reception among the French, so much so that it could be considered even more meaningful and important for them than the original English theory was in its own context? “French precision,” says Diderot of Condillac’s Essay on the Origin of Human Knowledge, “has overcome all of the length, repetition, and disorder which prevail in English works, and clarity, that companion of precision, has shed a vibrant and radiant light upon the dark and difficult features of the original.” —The reason for this lies in the fact that Condillac’s doctrine asserts even more clearly than Locke’s philosophy that both the consciousness and the character of the human being depend upon actual circumstances.

If the whole of our thinking and acting can be explained on the basis of sensory impressions, then it is grounded on the coordination of certain factors around us in our actual environment and within our physiological constitution. Therefore, the distinct modes of behavior of human beings—their level of culture (Bildung) or depravity, their criminality or their congeniality—can no longer be derived from the higher or lower attunement of their soul, from distinctions in their level of intellectual or spiritual endowment. Rather, all of these facts must be referred back to the empirical relations which make up the world, and because of which human beings with originally equal capacities have been formed so differently from one another. Thus, the configuration of social conditions, the social situation, the upbringing and laboring of the individual, their external life circumstances are made the determinant powers of the existence and development of human beings, and the conscious organization of reality replaces any search after inner redemption or through one’s relationship to some afterlife. This is the essentially materialistic character the enlightenment, and it is through this that the enlightenment is connected to more modern sociological and historical materialist theories. In a certain sense, the enlightenment is their precursor.

Thus, it is entirely irrelevant whether Condillac himself spoke about an immaterial soul or attributed all sense-impressions to it, and thus the habits and the functions these sense-impressions condition, or whether Condillac directly made the physiological system of the human being the bearer of its sensations. When one reads in today’s textbooks that Condillac was indeed a “sensualist” but “by no means a materialist,” this only proves that the distinctions between previous philosophical doctrines, some of which may still be useful criterion for the classification and evaluation of philosophies in the era of Hobbes and Descartes, fall short in any attempt to appraise the enlightenment; it also proves the limitations of this approach have yet to be recognized. Previously, the concept of materialism had been defined by the fact that, in opposition to idealism, it denies the production of actuality from thinking alone, just as, in opposition to spiritualism, it denies the possibility of autonomous spirits independent of the existence of physical bodies.

In the course of history, this definition has been reduced to the materialist thesis that only changes in the actuality of nature and society are to be considered the causes of changes in individual consciousness and culture in general, but not the reverse. This is not to say, however, that the older forms of physical materialism did not have their own role to play in later developments in the conception of materialism. This physical materialism is perhaps most consistently maintained in the formulations we find in the system of the enlightener La Mettrie. This does not mean, however, that one ought to draw a fundamental distinction between Condillac and the materialists just because the Abbé and tutor of the Duke of Parma may have declared that the soul is immaterial in a handful of passages. Diderot, for instance, held completely divergent intuitions with regard to this subject over the course of his life. Someone could write a treatise about his materialism, focusing on the period of his life in which he assumed the basic materiality of the soul, just as well as they could write a treatise about his immaterialism, focusing on the period of his life in which he assumed the basic immateriality of the soul—just as one might arbitrarily use his ‘deistic’ or ‘atheistic’ professions as principles for classification, division, and periodization of his work. The only argument that needs to be made against such a procedure is the likelihood that these thinkers would have the opposite opinions by dinner that they’d argued for themselves earlier that afternoon. In metaphysical matters, they were as generous as they were frivolous. Condillac’s theoretical philosophy has provided the foundation and confirmation for the reorientation of all interest towards the possibility of changes in the natural world, and above all to the doctrine of society.

[3.] Morality of Self-love (Selbstliebe).

Any well-read person can tell you that La Rouchefoucauld wrote a book of moral maxims and tenets, but the magnitude of psychological knowledge which it contains is almost as unknown to readers as it is discomforting. In a recent textbook on the history of philosophy, which is generally considered to be a competent one, one may read that he was a Duke, that he lived from 1613 to 1680, then peruse the titles of his works, and finally learn that on the basis of his observations of persons with high social standing at the time, he concluded that all of our actions have their origin and source in self-love. But that’s all. And yet, his one book contains more philosophical insight into the nature of the human being than any system of rationalistic philosophy. The book is not only unflattering to metaphysics and prevailing morality, but so critical that one might even say it already anticipates the psychology of the enlightenment as a whole. Here, we will mention only those features of his work which are also characteristic of the psychology of his successors, particularly those we find in the work of Helvétius.

The psychology of La Rouchefoucauld is based on the principle that self-love, l'amour propre, is the driving force of human action. It is difficult to determine this concept with any precision. It does not exactly coincide with what we ordinarily call egoism, nor with ‘self-love’ in the sense of those exertions we make with our own bodies. Naturally, both of these are included in the concept as well, but so are the other drives and passions. The idea behind the French doctrine that amour propre underlies human action is essentially the rejection of the rationalistic theory that moral principles from above could ever be the ultimate driver of any human behavior. Rather, according to the French psychologists, it is only an interest that is funded with and founded on the drives can condition an action, and providing rational grounds is never sufficient for uncovering the true causation behind that action. Whenever such a rational ground is given, particularly when it is a motive generally considered to be beautiful and noble, it becomes appropriate to ask what actual interest lies behind this facade. According to La Rochefoucauld, the specific constructs of “motives” and “dispositions” the individual might proudly display as images of their true character are rooted in prevailing social conventions. These constructs themselves are motivated by what is already considered praiseworthy and laudable in society rather than by the desire to give an accurate report of what does in actual fact drive our actions. This is not to say everyone falsifies themselves consciously; rather, in most cases, this reinterpretation is automatic, without requiring our conscious participation, occurring out of “habit,” as they expressed it in La Rouchefoucauld’s time. And even in our conscious self reform, self-love and our drives are secretly at work, concealing the driving forces behind our deeds from others as much as from ourselves.

“We are so often prepossessed in our own favour, that we often mistake for virtues those vices that bear some resemblance to them, and which are artfully disguised by self-love.”12

— Or: “Self-love is cleverer than the cleverest man in the world.” The mechanism through which actual, given psychological conditions are refashioned into the socially recognized virtues of our time is less something that is concealed from us than something beyond the reach of our knowledge.

“However hard one tries,” says La Rochefoucauld, “to hide their passions under the veil of piety and honor, there is always a point where they will reveal themselves.” It is precisely at this point that psychology takes as its point of departure to peer behind the veil and explore true human nature. Its task is to uncover the structure of the real causation behind our actions, and to unmask the disguises which have come about in correspondence with prevailing moral convention. We cannot hope to enumerate in full the treasure trove of insights into this subject the enlightenment unearthed, but only provide a sample from the works of La Rochefoucauld

“Justice is merely an intense fear that our belongings will be taken away from us. That is what leads us to be considerate and respectful for all our neighbour’s interests, and scrupulously diligent never to harm him.”13

“The constancy of the wise is only the art of keeping disquietude to oneself.”14

“When great men suffer themselves to be subdued by the length of misfortune, they discover that the strength of their ambition, not of their understanding, was that which supported them. They discover too, that heroes, allowing for a little vanity, are just like other men.”15

“Great actions, the lustre of which dazzles us are represented by politicians as the effects of deep design whereas they are commonly the effects of caprice and passion.”16

[4.] Critical Historiography.

This endeavor to penetrate through the play of semblances, to look behind constructs of motives on display for anyone to see, not only animated the substantial psychological literature of the enlightenment but also its grand tradition of historiography. The oft-repeated accusation that the enlightenment was unhistorical only demonstrates that the one who voices and stupidly repeats it deserves to vocally repeat their stupidity. Voltaire’s great historical works present such an enormous advance in modern historiography that to highlight the epoch-making contributions within the Essai sur les moeurs, his world history, and various historical works on special subjects, we would have to devote ourselves to his work alone. The manner in which he consulted documents and the testimonies of survivors for his historical depictions had a meticulousness that was almost unprecedented. Whoever leafs through the most respected book of world history in Voltaire’s time, Bousset’s Discours sur l'histoire universelle—a theological poem masquerading as history, according to which world history begins with the creation of the world, runs its course through all of the narratives of Holy Scripture, and, finally, ends with the apotheosis of the church’s victory over the heretics—will immediately appreciate the significance of Voltaire’s approach to critical historiography.

His guide, of course, is not sociological knowledge but contemporary psychology. When he radically suspends the function of divine providence, which still plays the leading role in history for Bousset, and instead allows natural laws to determine historical development, it is not social but psychological laws of motion he has in mind. It is the individual human being, ruled by self-love, that Voltaire hunts down behind all the legends of history, the human being who pursues their own individual, drive-determined purposes. Behind the concern a prince shows for his subjects, the courage with which generals and soldiers face death, the glories of war, the victories of the church, the discovery and colonization of faraway lands supposedly for the sake of the salvation of the natives—behind all the noblest customs and hallowed institutions of the civilized world, Voltaire finds hunger, ambition, jealousy, superstition, the fear of death, love, and hate. Voltaire does not go so far as to inquire into the social significance of historical facts; he does not realize that society itself follows different laws from those which govern the psyche of the individual, and that the study of society cannot be conducted solely by studying isolated individuals. But his psychology, which reaches back via Hobbes and La Rochefoucauld all the way to the Renaissance, to Telesio, all the way through Helvétius, enabled Voltaire to destroy the better part of the old legends of history, and cast the first light on whole series of historical facts. The fundamental principles of this psychology didn’t just yield results for the eighteenth century, but insights which have been partially confirmed by the most modern psychological research to date. When La Rouchefoucauld says: “Man often believes he leads himself despite the fact he is being led; and if his consciousness drives him towards a determinate goal, his heart leads him unconsciously astray towards another…”; when Vauvenargues (1715-1747), friend of Voltaire, says: “La raison ne connâit pas les intérêts du cour” [“Reason does not know the interests of the heart”]—this insight was first made explicit by Freud’s school. It has to do with the fact that the true determining grounds of our actions often escape our consciousness, that they “viennent du cœur” [“come from the heart”], as they said then, or stem from the unconscious, as they say today.

[5.] Role of Education.

For the enlightenment itself, it was particularly important that society and history have their origin in earthly, natural-human purposes, not in heavenly ones, and, therefore, that society and history must come to correspond with such purposes as well. Just as the consistent and thoroughly understood interest of the individual determines the moral law, so society can only become good to the extent it corresponds to the interests of its members. On this point in particular, there is a great difference between the harmonizing tendency of Locke and Locke’s English successors and the doctrines of the French. Helvétius no longer thinks that acting in one’s own, individual interest automatically means that one acts in the interests of existing society; conversely, he no longer thinks that this society and its state are automatically the most capable protectors and guarantors of the interests of all. “If citizens of the state,” he writes, “were no longer capable of bringing about their own particular well-being without simultaneously securing that of the general public, there would only be as many vicious people as there are fools.”17

The French enlighteners, standing on the precipice of the great Revolution, know all too well the contradictions which can arise between the ruling order and the interests of individuals, interests which the enlighteners hold up as the measure of the perfection or imperfection of this order. Their goal is that society be shaped in such a way that the particular interests of all the members of this society harmonize as much as possible with the institutions of this society. They do not take this agreement for granted, since in their country and in their era, it is plain that no such agreement exists; the English philosophers of their time, however, were associated with a social strata that was either already in power or, at the very least, not as obviously opposed to the status quo as was the Third Estate in France, which had formed something of an alliance—indeed, even something of a conscious and undivorced unity—with the poor tenants and peasants and proletarian masses, the Fourth Estate. When, therefore, Helvétius declares that virtue is in every case the course of action which corresponds to the common good, this does not mean virtue must benefit the existing state, as it meant when the English thinkers of his time said the same, but rather that it was possible society had been so organized that its institutions were by no means, or no longer, in agreement with the preservation of the common good.

That one’s own, personal, individual interest, if only correctly understood and consistently pursued, coincides with the correct general interest of society—this is a point of view Helvétius has in common with the English; for it is the harmonizing, liberalistic, fundamental doctrine of the bourgeoisie, according to which the economic order of free competition, in which each pursues their own interests, is the best possible form of society. But in France, many political acts were still required for this order to be realized, and the French were still far from implementing this order. Therefore, in Helvétius, the same psychology of interests, and the moral philosophy grounded upon it, became a politically revolutionary theory at its core. “Human beings are not evil, but rather subject to their interests. One must therefore not complain about the wickedness of human beings, but of the ignorance of the legislators, who have always brought particular interest into conflict with general interest.” According to Helvétius, a good organization of society must be ordered in such a way that the private and the general interests coincide, and the best organization of all would necessarily be the one in which this coincidence obtains for the greatest possible number of human beings.

If we call “evil” those actions which are contrary to the state and “good” those which are conducive to the state, if we call vice an anti-civic disposition and virtue a civic disposition—the terminology of Helvétius as much as the English—then under the given circumstances, the it is the state which must be the cause of vice, or of the majority of vices, rather than the private individual. “The moralists have not yet succeeded,” says De l'esprit, “because one must dig into the legislation in order to deracinate the fundamental root of vice.” Were we to condense the basic content of the point of view held by Helvétius, which was in essence the point of view held by the French enlightenment on the whole, it would read as follows: human beings act according to their actual interests, the innermost motor of which is passion, self-love. They always seek pleasure and flee displeasure. This behavior is necessary and inherent to their physical nature. There are needs which are immediately and, so to speak, originally present in their nature, such as hunger, third, sexuality, warmth, and so on. These are relatively independent of society—that is, they recur in every form of society. There are other passions, other drives, such as envy, ambition, avarice, arrogance, which are dependent on, and change along with, changes in the form of society. Even these other passions and drives have a physical foundation of their own, and we cannot uproot them by moral condemnation. Nor does one have any right to call them evil; for they are just as immanent to human nature as all of our other drives, our drives in general. All have the same root: self-love. They only become ‘vices’ when they come into conflict with the existing social order, at which point they may become dangerous and lead to the downfall of this order.

As matters stand, society is, according to Helvétius, badly organized and destined for decline. Here he goes even further than his peers, for he not only attacks the institution of Catholic absolutism, the influence of the Church and the monstrous system of justice, but he also hits on a point that concerns the very essence of the bourgeois order itself. He speaks of the relation between two classes, the rich and the poor, as he expresses it, and that the distinction in the standard of living between the two is so enormous, and that work for the poor is so oppressive and hopeless, so joyless, that there can no longer be any talk of a union of private and general interests. He predicts this society’s collapse. Here is the point where the connection between these doctrines of the enlightenment and latter-day socialism becomes clearly visible. It is self-evident that the demand for the organization of human society according to the principle of adaptation to the natural interests of the greatest possible number of its members, the demand for the most rational configuration of social relations possible—this could not even be laid to rest even after the French Revolution, after the expansion of the economic order of free competition. The legacy of the social critique of the enlightenment, which originally referred to conditions under absolutism, was taken over after the revolution by the socialist critique oriented against the bourgeois order—in the first instance, that of the French and English utopians: Babeuf, Fourier, Cabet, Owen and others. For at its core, the doctrine of Helvétius is materialistic and revolutionary: the interests of human beings, according to which society should be guided, are not fictitious, ideal interests, and which are merely postulated, as was sometimes the case with later psychologists of “interest,” but rather the interests of human beings oriented towards the production of materially bearable living conditions which society must satisfy. Helvétius is of the conviction that these interests must be satisfied above all by institutions, and that, therefore, the relation between the “deux classes” must be changed. All of the so-called higher interests, everything which concerns the various strata of culture in the narrower sense, is grounded on derivative passions conditioned by society rather than immediate ones, and a change in society must therefore be directed towards the primary, factual, and material interests of human beings instead.

This view of the significance of Helvétius’ philosophy seems to conflict with his doctrine that everything depends on education and can be made right by it. “The more perfect education is,” he says, “the happier the people.” The title of his main work is: On Man, His Intellectual Faculties and His Education (1772), and the first chapter of section X. is entitled: “L'éducation peut tout,” education can do all. But if you don’t simply rely on the textbooks, but read what Helvétius understood by education for yourselves, you will discover he never flirted with the idealistic delusion that the moral admonitions and beautiful ethical precepts of well-intentioned instructors—such as those of Pestalozzi or Fichte, to give a somewhat more contemporary example—are capable of changing society for the better. In the chapter mentioned above, we read: “Education makes us what we are. If the Savoyard, from the age of six or seven years, be frugal, active, laborious, and faithful, it is because he is poor and hungry, and because he lives, as I have before said, with those that are endowed with the qualities required in him; in short, it is because he has for instructors example and want, two imperious masters whom all obey. — The uniform conduct of the Savoyards results from the resemblance of their situation, and consequently the uniformity of their education. It is the same with that of princes. Why are they reproached with having nearly the same education? Because they have no interest in enlightenment, having only to will, and obtain their real and imaginary wants. Now he who can without talents and without labor satisfy both of these, is without motive for conscious activity.”

It is clear that ‘education’ here means something completely different from what we usually take it to mean: here, it encompasses the totality of the actual conditions of life, under which a human being develops, and not just what one has been taught in school or by instructors. When Helvétius therefore declares the whole development of human beings depends on education, this corresponds entirely to the materialistic point of view that material relations, the arrangement of which is dependent upon society as a whole, and above all the economic situation, condition the behavior and so-called character of human beings.18

Here too we see—as already explained by Condillac—the great significance of Locke’s epistemology for the enlightenment. For if, in the rationalistic manner, one were to attribute innate concepts and truths to the soul as an independent, active principle with its own functions, in opposition to explaining all knowledge by deriving it from external experience, then no external relations could ever have played such a role anyway, and the doctrine of an unconditioned inner centrum and character have become ineradicable. The empiricist epistemology of the enlightenment was grounded in its grand, critical tendencies. The doctrine of experience as the singular source of knowledge was necessarily connected with insight into the role of external living circumstances in the development of human beings. But while for Locke, experience, that is, the supply of simple ideas, depends solely on physical stimulation, Helvétius has the further realization that experience is just as conditioned by social relationships. Our experience presupposes not only the physical constellations which can be attributed to us in any one case, but equally presupposes the state of social development in which we find ourselves. The lawful progress of knowledge cannot be grasped by a few concepts borrowed from physics or those which concern the individual subject; rather, sociological, social categories are always required. Thus, when Helvétius explains the development of a specific science, namely the science of education, he explains that its progress, “just as that of legislation, always corresponds to the progress of human knowledge on the basis of experience; an experience which always presupposes the union of human beings in society.”

To this he adds expressly that the experience of each individual depends not only on the fact he is part of society at all, but more specifically on which profession or social position he occupies. According to Helvétius, all knowing is—and in this, he is in agreement with the enlightenment as a whole—comparing and judging, the knowledge [Wissen] of similarities and differences, and thus the determination of relationships: either of relationships between things or between things and myself. The givenness of these relationships, as well as the selections made among those which are given to us, depends upon the social situation of the one who experiences them. The priest encounters different relationships, and his interest compels him to establish different relationships, in the fullness of the given than does the merchant or the poor tenant farmer. Experience and knowledge are not just individual, but social facts. It is true that both are necessary conditions for any change in society, but it is equally true that, with any change in society itself, knowledge and science are also changed. Therefore, according to Helvétius, neither has an absolute value, but rather, like other achievements, both serve certain interests.

Since we have already said so much about state and society, we should at the very least mention the name of the philosophy most universally considered the true political philosopher of the enlightenment: Montesquieu (1689-1755). After he already published a rather sharp critique of the French situation in the Persian Letters (1721), he exposited his positive doctrine of the state in his main work, Esprit des lois [The Spirit of the Laws] (1748).

It is a purely bourgeois theory, greatly influenced by Locke, which demands a constitutional monarchy with a bicameral system. However, not all citizens are to vote in the House of Commons, but only those who are not completely dependent in standing. What is most commonly known about Montesquieu is that he wanted to separate not only the two powers of the state, the legislative (parliamentary) and executive, but maintain their separation from the powers of the judiciary as well. The reason is exceedingly simple: in France, at the time, the court would throw anyone who happened to displease it into prison by means of totally arbitrary arrest, the infamous “lettres de cachet,” whereas in England such things were made impossible by the Habeas Corpus Act (1679). Therefore, Montesquieu had to consider not only the idea of parliament control over the court, but the complete independence of the power of the judiciary, as particularly attractive prospects in the task of putting an end to the arbitrariness of absolutism. Even more important for future philosophy, however, was Montesquieu’s theory that was originally conceived on the basis of his impressions in England. The fourth chapter of the 19th book of Esprit des lois opens as follows:

Mankind are influenced by various causes: by the climate, by the religion, by the laws, by the maxims of government, by precedents, morals, and customs; whence is formed a general spirit of nations.19

This “esprit général” means the total culture of a people, and it was from this that Herder and his romantic successors in Germany would later develop the concept of the “Volksgeistes.” But whereas for the German philosophers, this concept would come to mean an ultimate and indissoluble unity, and would eventually be metaphysically hypostasized into something primordial, the ideal and essential being [Wesenheit] underneath or above each expression of social life, it has the exact opposite function for Montesquieu. Wherever—and this theory has the same significance for all the French enlighteners—we encounter something like a fixed, national character, our task consists in explaining this character on the basis of a set of conditions under which it has grown. Considered in isolation, the “esprit général“ is nothing primordial (or, as one might overhear on occasion in a poetic turn of phrase, a “living idea in the radiant garment of the Godhead”),20 but is in fact the product of very real causes which can be sought out and determined, including the nature of the climate, political relationships, traditions, customs, and so on.

It is not just that Montesquieu mentions material conditions, but that material conditions are for him the first and ultimate ground for any explanation of the esprit général; for example, he connected the autocratic form of government in specific countries to the fact that the agricultural ties of its inhabitants bind them so closely to nature they need not concern themselves with political freedoms. For Montesquieu himself, the doctrine of the “spirit of the people” is put wholly in the service of an analytical conception which reduces the more rarefied, more meaningful, more structured, more individual elements to what is more common, more meaningless, more partial, and more lowly in general. Throughout the whole of the enlightenment, there is a tendency to dissolve given structured unities into the parts which compose and condition them; there is the conviction that neither nature nor society, neither the physical world nor the human being, are self-subsisting and self-enclosed unities, but rather complex structures which may rightly be disintegrated into the base and meaningless parts out of which they are composed. The enlighteners are entirely lacking in deference to the status quo, have no respect for whatever has naturally come to be, but are instead driven by the desire to know partial connections and elements in order to guide and refashion things for their own purposes.

That sheer wonder which Plato once described as the basic philosophical attitude, and which Spinoza subsequently scorned, is alien to the enlightenment as well; science is regarded as the means of arranging the world according to human purposes; thus, it never remains at the level of unities, but seeks to learn about relationships, relations of conditioning, and partial laws; thus, it seeks to see beyond the facade and learn the mechanism. If one were to describe this movement as rationalistic in this sense, rather than the sense mentioned earlier, and has in view the universal mastery of nature by human beings; in the sense that science here consciously serves human purposes and human institutions—then, one may well call the enlightenment rationalistic, but it is nevertheless no less opposed to metaphysical and epistemological rationalism. One might, and not without reason, describe it as corrosive and destructive, but one should know that, without this intellectual dissolution, the conscious control and construction and bettering of the natural course of physical, biological, and social matters is in not possible. What the enlightenment advanced under the title of “reason” is action on the grounds of the most progressive knowledge. Even the enlightener most skeptical with respect to the influence of reflection and science and least immune to the oppressive effect of Pascal’s thought, Vauvenargues, wrote: “The falsest of all philosophies is that which, under the pretext of freeing human beings from the whirlpools of passion, advises them to do nothing, let themselves go, and forget themselves.”21 We should act consciously, and consciously bring about changes—and when Montesquieu speaks of esprit général and explains it on the basis of a host of individual factors, the objective meaning of this doctrine is that even the spirit of the people can also be changed, that even the culture and character of the people can be modified and guided in a determinate way by consciously changing their conditions.

[6.] Physical Materialism.

Such an attitude towards the world, and conception of the role of science, is the basis upon which everything which one might call the materialism of the Enlightenment in the narrower sense rests, and which, in the language we’ll be using here, essentially means physical materialism. As has already been said, this intuition received what is perhaps its most consistent expression in the philosophy of La Mettrie (1709-1751). His pair of writings Man as Machine (1747) and Man as Plant (1748), in addition to his treatise on happiness (Anti-Seneque) and the Epicurean system (Système d'Epicure) present a certain kind of unification of Lockean sensualism with the attempt, initiated by Descartes and advanced primarily by doctors, to arrive at a mechanical construction of the human being. The meaning of this philosophy essentially lies in the possibility of acquiring precise knowledge of the material changes which affect all biological beings to the end of inducing them at will. Because such changes are the only ones which can, strictly speaking, be known, and because spiritual-intellectual events are in any case dependent upon them, such material movements are considered the sole actual [movements in the human being]. It is telling that La Mettrie was himself a doctor as well. Even more significant than the writings of La Mettrie is the system of Baron d’Holbach (1723-1789), who, just as his friend Grimm, left Germany for Paris and made a home for himself there. His Système de la nature, which has been often referred to as the Bible of materialism, achieves a union between mechanical materialism and the psychology of Helvétius. The forces of physical nature are located alongside the motive forces of the psyche, but in such a way that each individual psychic process is expressly coordinated with a physiological movement of the nervous system. The Système is a greater achievement than the works of La Mettrie; it contains a codification of the most significant findings of the natural sciences and psychology of his time, and to an even greater degree than the Encyclopedia.

The Système de la nature, like so many other works of the Enlightenment, did not appear in Paris or France, but printed in Holland, and was then published under a fictitious name in London in 1770. It expresses the fundamental principles of the mechanistic system, the physical materialism of the Enlightenment, in clear, unambiguous form and without compromise. He writes in one of the principal chapters:

If experience was consulted, in the room of prejudice, the physician would collect from morals, the key to the human heart: in curing the body, he would sometimes be assured of curing the mind. Man, in making a spiritual substance of his soul, has contented himself with administering to it spiritual remedies, which either have no influence over his temperament, or do it an injury. The doctrine of the spirituality of the soul has rendered morals a conjectural science, that does not furnish a knowledge of the true motives which ought to be put in activity, in order to influence man to his welfare. If, calling experience to his assistance, man sought out the elements which form the basis of his temperament, or of the greater number of the individuals composing a nation, he would then discover what would be most proper for him,—that which could be most convenient to his mode of existence—which could most conduce to his true interest—what laws would be necessary to his happiness—what institutions would be most useful for him—what regulations would be most beneficial. In short, morals and politics would be equally enabled to draw from materialism, advantages which the dogma of spirituality can never supply, of which it even precludes the idea.22

For d’Holbach, materialism is the presupposition of any rational medicine or politics. He writes:

Politics ought to be the art of regulating the passions of man—of directing them to the welfare of society—of diverting them into a genial current of happiness—of making them flow gently to the general benefit of all: but too frequently it is nothing more than the detestible art of arming the passions of the various members of society against each other,—of making them the engines to accomplish their mutual destruction,—of converting them into agents which embitter their existence, create jealousies among them, and fill with rancorous animosities that association from which, if properly managed, man ought to derive his felicity. Society is commonly so vicious because it is not founded upon Nature, upon experience, and upon general utility; but on the contrary, upon the passions, upon the caprices, and upon the particular interests of those by whom it is governed. In short, it is for the most part the advantage of the few opposed to the prosperity of the many.23

Authority commonly believes itself interested in maintaining the received opinions: those prejudices and errors which it considers requisite to the maintenance of its power and the consolidation of its interests, are sustained by force, which is never rational.24

This is the apex of this materialism: struggle against the badness of that which exists and the striving to change it. It is necessary to investigate in detail the physical conditions for the ideas of individuals and the generality to influence such conditions according to human purposes. This influence has until now, according to d’Holbach (just as for Helvétius), operated beyond the control of the public; the powerful have exercised this influence in secret, and to the detriment of the human being. Now, however, the exercise of this influence is to become a universal affair, and, on the grounds of the investigation into and knowledge about all such physical conditions, both the individual and society as a whole are to be given the best of all conditions for their development.

This tradition had its initial and direct effect in relation to its primarily medical purpose. Following La Mettrie and d’Holbach (as well as Condillac), there were a number of doctors who set themselves the task of studying the dependency of our ideas on physiological conditions. Chief among them were Cabanis (1757-1808), the doctor of Mirabeau, and Destutt de Tracy (1754-1836). They constructed a materialistic psychology for medicinal purposes. They sought to create a “natural science of spirit,” one in which every movement of thought would be explained on the basis of its physiological conditions—that is, on the basis of processes which take place in the nervous system. In the immediate aftermath of the great revolution, there are almost no other endeavors which might be considered scientific philosophy apart from this school of psychology. The French Convention established a department for the “Analysis of Sensations and Ideas” in the National Institute in 1796, officially recognizing the views of De Tracy and his colleagues as the one legitimate school of thought. This is also where the designation of “ideology” came from—originally, it designated the study of and investigation into the material dependency of consciousness; today, “ideology” is typically reserved for designating consciousness itself, false consciousness, distorted by material influences. At the same time as the “ideologists” practiced their science in France, there were several doctors in England who attempted to do so as well.

David Hartley (1705-1757), as well as his student, Joseph Priestley (1733-1804), the scientist who discovered oxygen, stand in close proximity to these ideas of the French. They set their sights on a physics of the soul that would take its place alongside the grand developments in physics since the time of Newton. For this reason, they would eventually become the founders of Assoziationspsychologie. For his own part, Priestley was an enthusiastic supporter of the French Revolution, and his investigations into matter and spirit are completely free of the idealistic tendency which would later be characteristic of Assoziationspsychologie. For the sake of clarifying once more what the materialism of the Enlightenment in the narrower sense looks like, we may refer to a grand and important passage from the beginning of d’Holbach’s Système de la nature:

“Man has always deceived himself when he abandoned experience to follow imaginary systems.—He is the work of nature.—He exists in Nature.—He is submitted to the laws of Nature.—He cannot deliver himself from them:—cannot step beyond them even in thought. It is in vain his mind would spring forward beyond the visible world: direful and imperious necessity ever compels his return—being formed by Nature, he is circumscribed by her laws; there exists nothing beyond the great whole of which he forms a part, of which he experiences the influence. The beings his fancy pictures as above nature, or distinguished from her, are always chimeras formed after that which he has already seen, but of which it is utterly impossible he should ever form any finished idea, either as to the place they occupy, or their manner of acting—for him there is not, there can be nothing out of that Nature which includes all beings. Therefore, instead of seeking out of the world he inhabits for beings who can procure him a happiness denied to him by Nature, let him study this Nature, learn her laws, contemplate her energies, observe the immutable rules by which she acts.—Let him apply these discoveries to his own felicity, and submit in silence to her precepts, which nothing can alter.—Let him cheerfully consent to be ignorant of causes hid from him under the most impenetrable veil.—Let him yield to the decrees of a universal power, which can never be brought within his comprehension, nor ever emancipate him from those laws imposed on him by his essence. The distinction which has been so often made between the physical and the moral being, is evidently an abuse of terms. Man is a being purely physical: the moral man [viz., in French, ‘moral’ means that which is spiritual or intellectual as well — M.H.] is nothing more than this physical being considered under a certain point of view; that is to say, with relation to some of his modes of action, arising out of his individual organization. But is not this organization itself the work of Nature? The motion or impulse to action, of which he is susceptible, is that not physical? His visible actions, as well as the invisible motion interiorly excited by his will or his thoughts, are equally the natural effects, the necessary consequences, of his peculiar construction, and the impulse he receives from those beings by whom he is always surrounded. All that the human mind has successively invented, with a view to change or perfect his being, to render himself happy, was never more than the necessary consequence of man's peculiar essence, and that of the beings who act upon him. The object of all his institutions, all his reflections, all his knowledge, is only to procure that happiness toward which he is continually impelled by the peculiarity of his nature.25

The expectation of celestial happiness, and the dread of future tortures, only served to prevent man from seeking after the means to render himself happy here below.26

This, then, is the materialism of the Enlightenment in the narrower sense. Naturally, neither d’Holbach nor this materialism ever denies the fact that human beings think, but they is of the conviction that the thoughts of human beings are explicable on the basis of material circumstances, and furthermore that with a change in their material circumstances, whether of the physical constitution of the individual or of their living conditions as a whole, the thoughts of human beings will change as well.

[7.] Rousseau.