Social-Philosophical Exercises: Weber, Hegel, Marx (1930/31).

Minutes From Horkheimer's Forgotten early 30's Lectures.

Editor’s note: Below, you’ll find translations of the minutes transcribed during Horkheimer’s seemingly forgotten lectures on Max Weber, Hegel, and Marx, delivered between the fall of 1930 and the summer of 1931, around the same time Horkheimer officially assumed the position of director of the Institute for Social Research. From his 1932 essay “Hegel and the Problem of Metaphysics” to his fragmentary Marxian anti-metaphysics, the 30/31 lectures resonate strongly with much of Horkheimer’s writings from the same period. The transcripts are rough. I haven’t been able to identify all of the speakers (e.g., “Solm-Rethel,” possibly Sohn-Rethel, whose name I’ve left as [S-R] below), let alone who is speaking at which point in the discussions. (On occasion the numbered lists will restart from “(1.)” mid-digression without any indication of a change in speaker.) From what I’ve been able to gather from the transcripts themselves, the minutes would often begin immediately following a presentation by one of Horkheimer’s students on a certain topic (e.g., an essay of Weber’s, Hegel on the family, etc.). In the near future, I plan to come back to these notes and include editorial notes on the specific passages in Hegel’s Philosophy of Right and several of Marx’s works (Capital, V. I-III, the Contribution of ‘59, The German Ideology, etc.) explicitly cited in the transcripts—or, as in the case of Marx’s “Theses on Feuerbach,” texts that are repeatedly alluded to. Even so, the lecture minutes seemed worth posting in this form because of the uncharacteristic directness with which Horkheimer develops his conception of the anti-metaphysical dialectic in Marx. Along with some recent research into Horkheimer’s early Marx/ism Studies (ca. 1919-1927), this post will be part of an ongoing project to reconstruct the distinctive critical-materialist perspective in post-Kantian philosophy Horkheimer develops in the late 1920s through his constant clashes with the metaphysicians, positivists, neo-Kantians, Gestalt psychologists, and theologians of late Weimar intellectual life.

Contents.

A. Seminar from Professor Horkheimer on [Max Weber’s] “Philosophy of History” (8/4/1930).1

B. Key-Words for Horkheimer’s Lecture on [Hegel and Marx] (ca. 1930?).2

C. Social-Philosophical Exercises—Summer Semester (1931).

A. Seminar from Professor Horkheimer on [Max Weber’s] “Philosophy of History” (8/4/1930)

Theme: To what extent is uniformity of history—in the sense of Kant’s ‘uniformity of nature’—possible for Max Weber?

H: Max Weber didn’t just seek to develop a few methods for historiography, but determine the essence of “history” itself. He has divergent intuitions: (1) Nature is a generalized product of abstraction of human cognition—history, however, is a real process of humanity. This is an inheritance of the classical-idealistic view, which is retained from Kant to Rickert. (2) Positivist conception: “history” is nothing but the elevation and isolation of the actions of individual human beings from out of a heterogeneous continuum; historiography an organizing measure according to subjective points of view. There are no autonomous values; values are valid because and to the extent that human beings recognize them. Because in certain times determinate values are recognized, historiography, in relationship to these values, is possible. But there is no uniformity of history in the sense of a counterpart to Kant’s ‘uniformity of nature.’

[Willy] Strelewicz: The contradiction lies somewhere else: history is for Max Weber the history of cultural ideals; the development of cultural ideals is the true process which plays out behind the backs of human beings and is not susceptible to positivist attack. The contradiction lies between the rational universal validity of the value-spheres and their perpetual historical change; the value-spheres, in relationship to which historical cognition is constituted, are themselves changeable.

H: Certainly, for Max Weber the historian is positioned within the historical process. The notion that “the process of [social] values plays out behind the backs of human beings” is no Weberian conception. Cultural values aren’t realities as values—rather, on the one hand, cultural values are the presupposition of the possibility of history and, on the other, evaluations are the thoughts of individual human beings; values are the intended meaning of history. For human beings who recognize such values, they cannot be criticized according to the criteria “true” or “false.”

Gerth: Emphasizes the role of the irrational in Max Weber’s concept of history. “The emergence of a new charisma” is the motor of history from within it. History is undoubtedly full of interest-groups, but what is decisive is the appearance of a great leader, “charisma is the switchman [Weichensteller] of history.” Since the development of capitalism, the great apparatus of organization, such great individuals no longer appear. Max Weber personally hoped that a new, charismatic leader would step onto the stage.

H: “The emergence of a new value, a new charisma from within”—this formulation would be a serious inconsistency for Max Weber. To the contrary, it is precisely in his positivism that the irrationality endures, and from which historians draw their “arbitrary” image of history [Geschichtsbild].

[Presentation by Ms. Apolant on Max Weber’s essay, “Wissenschaft als Beruf.”]

The discussion revolves around the following propositions: scientific progress is the process of the rationalizing of life, the expanding knowledge of technology, the broadening of possibilities for thinking. The value of individual scientific goals is not logically provable, different at different times. The tension between the value-spheres “religion” and “science” is unbridgeable. Absolute values can only be actualized in the personal relationships of the researcher; they are not to be sought in research itself.

Strelewicz: For Max Weber, the foundation of science is its truth-value [Wahrheitswert], even for the positive sciences. —In the value-sphere which underlies the science of history in Max Weber’s account, there is something equivalent to Kant’s “thing-in-itself.” The value-spheres—according to Max Weber—change in an irrational manner, however, for Max Weber, and are not, as for Kant, postulates of practical reason (the Good, the Beautiful, etc.).

H: The relationship all science has with the truth-value is its logical postulate, not its metaphysical foundation. Truth-value as such possesses neither reality nor changeability. —“Eternal values” exist for Rickert, not Weber. Rather: in certain times, human beings agree in certain values, and, to the extent they agree, “history” is possible. The phenomenologists initiate their critique of Max Weber’s conception of value-spheres on the grounds that values are, for them, effective realities. Reference to the next lecture—on Scheler.

B. Key-Words for Horkheimer’s Lecture on [Hegel and Marx] (ca. 1930?).

Hegel solves the epistemological question of the position of the subject relative to the object via inclusion of the subject, the ego, in the process of the whole. For Hegel, however, consciousness is still what is constant, unchanging. And yet, consciousness must be included within the process of the whole as well as something thoroughly variable, changeable. Nothing is independent of the historical process. Spirit and consciousness are just as determined by nature as anything else. Neither spirit nor consciousness can be opposed to nature, but are part of the process as a whole, and are modified and changed in its course. The logical considerations of the ego and consciousness about nature and the course of events are in no way identical with nature and the events themselves.

All absolute statements are impossible. The cover-up of the recognition of this impossibility through the mystification of society and its superordination, as if it were God, above all events is just as impermissible and, fundamentally, consists of metaphysics under the sign of its opposite.

Nature and society are shaped by human beings. Simultaneously, there is a reciprocity between them. Society shapes nature to a high degree, and nature largely determines society. The development of nature, spirit, and society is a unified process.

On Method.

Development does not proceed in a straight line, but in leaps and bounds, revolutionarily, through contradictions. As long as you remain with a single phenomenon as such, it cannot be comprehended. Each phenomenon can only be grasped as a part of the totality, in its manifold connection to this totality. This totality alone makes it possible to meaningfully grasp its parts, while the part is necessary for any understanding of the totality. The phenomenon as such cannot be conceptualized. One must investigate the constitution of this phenomenon, how it functions, changes, came into being.

The Hegelian dialectic must be transformed into a Realdialektik, as Marx has done. The contradictions between thoughts do not exhaust the problematic as a whole. The contradictions must be rendered visible in actuality, whereby actuality and thought are not rigid opposites—contradictions are to be exemplified in actuality. (Forces of production—relations of production, etc.)

Whereas Hegel grants the dialectic and its laws eternal validity, Marx positions the dialectic within the stream of historical becoming and events and regards it precisely as transient, historical, and mutable as actual life.

Problem of Freedom.

According to Hegel, freedom is only possible when realized in the state, in the family, etc. Freedom—Necessity. How is the concept “law” to be understood? Is law the same as coercion? Can one speak of an internal lawfulness? Does what occurs on the basis of laws occur as a result of internal coercion? But there is no ‘internal necessity’ to speak of. Nothing of the kind exists. The law of gravity, for instance, says nothing about the body which falls “on the basis” of this law having an internal necessity to fall. The lawfulness can, at most, be formulated such that it can be declared: if A occurs, then B must occur as well. However, this ‘B’ doesn’t occur because of an internal necessity, but rather because it is causally determined by A’s occurrence. But it is also entirely possible that the lawfulness in question instead takes the form of: if A occurs, then B, C, D must occur. Because we long for determinate events, or seek to prevent them, we attempt to establish necessities and lawfulnesses. Law is, however, in the first place solely an order-concept which is not immanent to things themselves but created by us. None of our explanations are created for the sake of understanding things themselves, putting ourselves in their place, as it were, but rather to shape the course of things, to become capable of intervening in the sequence of events. (cf. Marx’s 11th Thesis on Feuerbach.)

The external rule, however, is no internal necessity. Human beings think about reasons for their actions that are completely different from what the reasons for their actions in fact are (e.g., the findings of psychoanalytic inquiries).

Marx concretizes the concept of freedom by stripping it of its mystical trappings. The concept of freedom, which still has a metaphysical shape for philosophers, thus takes on a living, full-blooded significance for Marx. By freedom, Marx understands the degree to which human society is no longer subject to the pressure to labor. Not the opposition of “spiritual freedom—spiritual necessity,” but of “freedoms of life—necessities of life.” (Exemplified by: wealth vs poverty, freedom in general vs being-locked-up-in-prison.)

The necessity which rules over human beings, created by human beings themselves but nevertheless eludes their will—economic necessity. Therefore, economic necessity is transmuted into a coercive necessity to which human beings must submit themselves—blindly, and without any possibility of conscious intervention into the sequence of such necessities. Socialism—freedom, for though economic necessity will still exist, it will be consciously shaped by human society—necessity will cease to be blind.5

And so, according to Marx, freedom is the condition in which human beings are no longer forced to blindly obey economic compulsion, but in which they have the possibility of consciously shaping their economic situation. Freedom—dignified human existence.6 Menschenwürdig (human dignity)—no metaphysical concept, but an utterly real condition, something that is capable of being exemplified in everyday life. When a 12-year-old child is forced to work for 12 hours a day in a factory—this is undignified. (Cf. Engels, Lage der arbeitenden Klassen in England.) A human being lives in an undignified way when the sphere of their actions is too narrow, when their life inhibits or obstructs the unfolding of their human capacities, when their life turns the human being into, so to speak, an animal, a machine without consciousness. (This thought is to be elaborated with further examples.)

Weltanschauung.

Three tendencies up for debate.

1) Philosophical materialism

2) Historical Kantianism

3) Empirio-criticism

Confrontation with these three tendencies: Plekhanov, Max Adler, Mach-Avenarius on the one side; Lenin on the other.

Plekhanov’s central views are briefly reproduced. Plekhanov declares that being a Marxist is necessarily connected with being a philosophical-materialist.

The materialist Weltanschauung consists of a series of theses that present the world as a whole, as what is—as matter, as its movement. Urstoff. Only what science teaches us is to be believed; struggle against the church. Philosophical materialism had a substantial and important function in the enlightenment—a precursor that paved the way for historical materialism and the overcoming of idealism. Today, however, it is easy to refute. Today, rigidly clinging on to mechanistic materialism is either simply reactionary or amounts to empty phraseology.

For Marx, it is not only the movement of matter and the relationships of matter that are actual, but the relationships between human beings and their movement. The negative, the critical aspect—Marxism shares this with philosophical materialism. Yet, philosophical materialism is ahistorical. It ignores the historical process and the transformations of matter within it. What we’ve said about society above—namely, that some mystify it and equate it with God—materialists do with matter, and so arrive at another absolute truth. Metaphysics. Truth is to be sought and worked out—but this means changing actuality.

Max Adler thinks that Marxism is insufficient for the explanation of relationships between human beings. Marxism must, therefore, be supplemented with a well-developed Weltanschauung and ethic. While the science of Marxism correctly establishes what is, it has yet to establish what the role of the human being is in being. How the human being should act—-this is an ethical question. Connection of Marx and Kantian ethics.

In the following lecture, Lenin’s book Materialism and Empirio-Criticism was discussed.

In the final lecture, questions were posed by the higher-ups, which were subsequently answered—by way of conclusion, Horkheimer presented a manuscript which could not be transcribed on account of time constraints.

C. Social-Philosophical Exercises—Summer Semester (1931).

Social-Philosophical Exercises I: Hegel, Summer Semester (1931).

(4/16/1931) [Preliminary meeting.]

(4/23/1931) [Review of Winter Semester 1930/31.]

(4/30/1931) [Hegel.]

I. Family and Society.

(1) Presentation coincides with justification.7 Whenever something is not in order, this derives from the fact that human beings do not have the right consciousness.

(2) The position of family and civil society in Hegel’s system.

(a) Consciousness must be consciousness of its own freedom in order to be philosophical consciousness. Consciousness itself is absolute totality, identical with all beings, subject and object identical.

(b) Problem of the absolute claim to truth. Either the truth I seek exists, in which case I would have to have the whole truth all at once, or one cannot claim that any one proposition has absolute truth.

(c) Logic: Idea. Nature: Idea in its otherness.

(d) The truth of nature needs justification in the system of philosophy. Fragments of knowledge can on occasion be recognized as false.

[Margin: Doesn’t this apply to any statement, for example those about society, crisis, etc?]

(e) Non-metaphysical concept of truth. Propositions are true if they involve a determinate expectation which is subsequently fulfilled.

(f) Objective spirit and its forms: family, etc., prior to law (property, right, wrong, punishment), morality (a subject which has the possibility of acting correctly, independent of external compulsion), ethical life (family, civil society, state deducted).

Absolute spirit—intuits itself: art; presents itself to itself: religion: cognizes itself: philosophy.

(3.) Ultimate motive: either system or no absolute truth.

(4.) Paper by Gert: The Family.

(a) Family is not subtlatable [aufhebbar], for otherwise spirit can never come to cognize itself.

(b) Marriage—Property—Education of children. Drive. Concubinage.

(5/7/31)

(1.) Colloquium on Hegel and his “System.”

(2.) Metaphysics and ultimate things: why is there a path from the logic to the nature-philosophy? (From whence comes the necessity for the idea to pass into its otherness, and is this remotely justifiable rationally, dialectically?)

(3.) The family in Hegel (repetition). Freedom = insight into necessity.

Question from Ms. [X]: on what basis is it proven that the universal is the good?

(4) Hegel Opportunist—Pantheist (All that exists is good!); but this is true of some Marxists as well (Lukacs)

(5.) Since the collapse of the Hegelian system, philosophy has been tasked with introducing another concept of cognition [Erkenntnisbegriff], since that of metaphysics has failed.

(6.) Hegel was neither reactionary nor revolutionary; such questions cannot be answered.

(7.) Re: the method of social philosophy for Hegel (Philosophy of Right, §§170-173).

(4a.) The individual is transient, what remains are the categories and those things which embody them.

(Re: 7:) Hegel doesn’t deduce the stages in detail, but rather only states that they are, and that the individual knows himself to be a member of the stage in question. He does not deduce the existence of the family in spite of its wealth, though he asserts that he does.

(8.) The significance of Feuerbach’s Hegel-critique.

(9.) Hegel “deduces” from individual cases, e.g., family and wealth, e.g., man as sovereign [Oberhaupt]. (§171 in particular demonstrates the dubiousness of his procedure!)

(10.) Only in the complete and perfect state is freedom actual! E.g., §177. Education for free personality.

(11.) Interpenetration [durcheinander] of empirical, historical, juridical determinations.

(12.) Ambiguity of Hegel’s methods in the words themselves, too. Real ground [Realgrund]? Legal ground [Rechtsgrund]? Philosophical justification [Rechtfertigung]?

(5/21/1931) [Volksbildungsheim.]

(6/4/1931)

(1) System of needs and inner necessity (= the law of value).

(2.) The three estates.

(3.) Example of: Hegel’s dialectic standing on its head.

(4.) So long as Hegel sticks to history, he is a materialist; but as a philosopher, he interprets historical events as the work of a divine idea.

(5.) Hegel explains pre-established harmony through the thesis of the cunning of reason; this enables actual history to produce precisely what was prefigured in the logic, etc.

(6.) Hegel and Prussian Feudalism.

(7.) Factual division of society justified through logic.

[Margin: Liberalism. System of Harmony.]

(8.) Pre-established harmony—cunning of reason (Hegel); law of value (Marx).

(9.) Drives of the individual are actualized through the interests of the whole. For Marx = profit-seeking = force of production.

(10.) Individuals participate in universal life solely as members of their estate.

(11.) Administration of justice, police, corporation, conscious reason

[Margin: §243/46]

(12.) Contradiction of civil society: the rabble! Police and corporation mediate between individuals and state.

(13.) Apology for world commerce, philosophical derivation of imperialism.

(14) Classic example of philosophical ideology in §245. With help of his ambiguous and irresponsible method, deduces that the rabble is produced… ; only, the richer class must ensure that the plummeting [Herabgesunkenen] do not sink beneath the concept of human beings! Yet, without property, they are not human beings at all. The state must accommodate them within its system, but only does so by relegating them to beggardom; the rabble is not determined economically but psychologically (as lazy, etc.). Against the right to work, and the utopians!

(15.) Through the existence of the rabble, the whole system is in fact overthrown. In principle: it is a slap in the face of freedom, but it is still blamed on the rabble themselves: it is schlechte Wirklichkeit. (Thesis—Antithesis.)

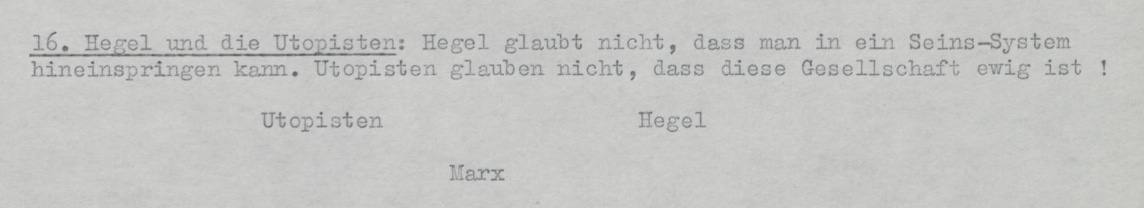

(16.) Hegel and the Utopians: Hegel doesn’t believe one can simply jump into a system of being [Seins-System]. But utopians do not believe that this society is eternal!

(17) Any method that seeks to deduce the whole of actuality as a rational one must fail so long as actuality is not in fact rational.

(18) Paper on: the state. In it, multiple references to the fact that no sense can be determined as to why certain individuals sink into the rabble and, thus, out of participation in the idea’s coming-to-itself. Analogous break in premature death: what is consciousness of the whole for since it seems to be a matter of chance whether one lives or dies?

Hasselberg asserts: pauperism is not a contradiction internal to the system, since Hegel had no eschatology, such that things are neither to be taken historically nor morally.

MH: In that case, there would have to be slaves—but this is precisely what Hegel declares impossible!

(6/11/1931)

(1.) MH: What do you understand by the state?

HY [?]: If you demand a definition, you have to say what it is you want it for!

[Bindung [?] and Tillich on the state.]

Status of each—power = necessary environment. Individual.

(2.) Paper on: The State in Hegel (§256ff.)

(3.) N.B.: what does the idea have to do with the shape of the state? Compare to Marx’s criticism of §262.

(4.) The state is a construct of the idea without any outside intervention.

(5.) State: Citizens. Purpose of the state = happiness of citizens. This is undoubtedly true, etc.

(From here, a direct path to: what matters is not the interpretation of the world…)

(6.) Marx: It’s not a matter of abandoning philosophy, but of actualizing it.

(7.) Distinction Marx—Hegel: that what underlies history is not the self-movement of spirit, but the class struggle of human beings.

(8.) v. Hasselberg: It is evident that dialectics cannot simply be conceived in terms of the categories. The objection that one simply substitutes the forces of production for absolute spirit is absurd.

(9.) What ensures the coherence of the state is the ethical will to subordinate oneself to the universal, the “Lust am Gehorchen.” In patriotism, the idea comes to life in individuals for the first time, to the extent the individual wills the whole.

(10.) The Prussian state is rational because the constitution that exists can be deduced from its logic.

(11.) Hasselberg and Sevenich say: Hegel is cheapened if one does not maintain what Hegel takes logic to be: for Hegel, logic is “yet something else.”

MH: What is that? Simply saying this sounds a little too cheap to me.

(12.) The “concept” in Hegel is something like a moment in a process that must be regarded as identical with the entire spiritual dynamic.

(13.) What lurks behind the defense of Hegel: Anyone who stands in opposition to a powerful state belongs to the rabble. Hegel’s system is written as justification for the state, just like 3/4ths of all philosophy of history today.

(14.) Logic structures events and decides on what is actually real.

Structuring work: Reason—Logic—Actual Events / Sheer Existing.

(15.) Hegel need not prove actuality is rational, since he brings this thought along with him! For the genuine idealist, everything that has had any power or that has been—it is meaningful, good; even for Kant: the thought that the thing-in-itself is the devil would never occur to him!

For materialism, there is no meaning inherent to reality irrespective of how things are going in the world, and so there is an enormous leap from here to the belief in a benevolent creator.

(16.) The difficulty of all idealistic philosophy, which did not know whether fascism or socialism was coming and now doesn’t know which of the two should be deduced as the rational alternative.

(17.) Idealism = any system in which the possibility of a theodicy can be conceived!

(18.) Not that all of this is simply the reverse for Marx, but the consistent idea of materialism is its contrary.

(6/18/1931)

(1) Hegel’s Theory of the State (Müller’s Paper)

(2.) Monarchy “corresponds” to the individuality of the state? Isn’t this just a symbol? (The hard problem of Hegelian philosophy.) To what extent does the monarch actualize unity when he replies to the speech of his councilors with: “I will”? What does this mean?

(3.) Sevenich: Regarding the concept of the state as something in-itself living, including the concept of the Monarch.

(4.) Can one regard the state as a person, or is this sheer symbolization?

(5.) Sevenich: The state must provide the opportunity for unity in multiplicity (Lorenz von Stein). MH: Is that really compulsory?

(6.) In any event, Hegel’s explanations involve grounding only of symbolic character, not existential character (or identity).

(7.) Gert: Why not elect a president for life? (Continuity under threat.)

(8.) In Hegel, there is in many cases an illegitimate transcending [Hinausgegen] of sheer correspondences.

(9.) The method of Hegel, which claims to be something completely different, —fundamentally does nothing but violate the rules of critical logic; law [Recht] draws it from a metaphysical principle. Identity is constructed from structural similarities.

(10.) When we take Hegel seriously, we always arrive at his thesis of identity—and we must believe, believe, believe!

(11.) Hegel and idealist metaphysics. Against Hegel’s truth, the positivist concept of truth. Judgment is true if its content can be found.

(12.) Monarchy as highest form of constitution. The representatives ought not be elected; this corresponds to atomistic principle.

[Margin: §314, §302 very important!]

(13.) Estates as presumptive organ.

(14.) Sevenich: Only the coming-apart [Auseinanderfallen] of state and society permits the formulation of sociological questions. Hegel hands society back over to the state through an utterly formal mediation.

(15) … so the state would collapse? But then Hegel’s philosophy would collapse alongside it; then an absolute philosophy would not be possible! Correspondences taken as philosophical-systematic justification, and therein lies the whole problematic. But for Hegel, it is of no concern whether the estates represent groups of human beings of a certain kind or other: they are still not permitted to contradict the government.

[Margin: §324]

(16) War is no absolute evil, but the forward-driving force in the developmental process of absolute spirit! In war, the true relation of individual and state is made manifest in its truest sense. The necessary movement of property.

(17.) State as substance of ethical life … cannot be wrong in foreign policy.

(18.) Fact that finitude of human being is “expressed” in pain: is this not just another relation of expression; why must it be this way and not another? I cannot get past the fact that it is entirely contingent and indifferent about which individual’s life and property is taken away.

(19.) Sevenich: Believes that there are substantial representations from the Middle Ages concealed in this. Representations of guilt and redemption!

(20.) Decisive point: what right would Hegel have to contradict if one were to judge him using the concept of the logic of the understanding.

(21.) Distinction between logic of the understanding—speculative logic. Hegel’s logic contains speculative metaphysics: thesis—antithesis—synthesis; already contains the contradiction: identity—subject—object.

(22.) Why is the opposite necessarily contained in the proposition, the contradiction to the thesis in the thesis?

(23.) Thesis points beyond itself, for it forces one to think its opposite / its contradiction as true.

(6/25/1931)

(1) Distinction: speculative logic and logic of the understanding [Verstandeslogik].

Then: the rose of which we speak here has nothing whatsoever to do with the one that blossoms and withers. But this means that all processes occur on the basis of an ever-identical substrate, i.e., metaphysics is tied to Aristotelian logic.

Our judgment leaves the subject unchanged; one cannot assign it and deprive it of one and the same predicate, yet: the rose blooms and withers.

(2) Concept only a name defined by us ourselves. So: the rose has withered = a name has withered? So: the word denotes nothing beyond itself?

(3) The problem is so kopflos because it is completely different for (a) general names than it is for (b) individual names; (ad. a) artifice, fiction; (ad. b) is name no longer! For what I intend is a reality.

[Margin: Blow against nominalism. It founders on the problem of the concrete individual.]

(4.) Why this particular summarization [Zusammenfassung] and not another? This question nominalism does not answer.

(5.) Bernardelli asks whether the utilization of the concept of substance rests on a necessary concept of reason.

(6.) It is necessary, however, to hold onto the content of concepts; therefore, no speculative logic is possible apart from the logic of the understanding.

(7.) [Speculative:] In attributing predicates to the subject, the subject changes! Why? Because the absolute thinks! (Hegel identifies reality with thought; the absolute is always that which is thought, at first in a completely abstract manner, pure being without any predicates, etc.)

(8) The typical definition [Bestimmung] of dialectics is from Marx, and not from Hegel. For Marx, “dialectic” is only consideration from all sides; for Hegel, it is the manner in which the absolute thinks itself.

(9.) Identity of subject-object leads by necessity to speculative logic.

(10.) Through the judgment, the subject only changes if the subject which is thought is identical to the subject which thinks.

(11.) Identity alone guarantees absolute truth and speculative thinking!

(12.) Presentation on: Philosophy of history.

(13) The definition of freedom in German Idealism (that which can only become actual by identification with what has already become actual).

(14.) Mysticism — pantheism — German Idealism.

(15.) Pauline thinking in Marx?

(16.) The general stage of self-consciousness of the Volksgeistes?

(17.) The role of analogy in Hegel.

[Margin: Level, Mixed-form, and its consequences Africa, the East, etc.]

(18.) Relationships between idealism and harmonizing ideology.

(19.) Is Hegel’s philosophy essentially a justification of that which exists?

(20.) Hegel is empiricist; Hegel is no empiricist.

(21.) Philosophy endeavors to bring what empirical researchers have discovered into a structure which is said to correspond with the life of things themselves; this structure, however, is not born of the devotion to the things themselves, but from the logic in which the concept thinks itself.

(22.) Hegel grants science a certitude and its actuality a veneer that one should not give to their science. “Science” = actual cognition. “Actuality” = that which should be!

Hegel is no utopian, but he is not, therefore, neutral—rather, he identifies utopia with actuality itself.

(23.) Idealist philosophy always says to us: science alone is not enough, and Hegel’s example proves this. Hegel still says there must be nothing in it which contradicts science.

(24.) Philosophical truth is only possible if there is a closed [geschlossene] system and the identity between subject and object.

(25) Consequences: the subject, which does not know what it says: “I, myself,” has a completely different science [than the one that presumes to]; such subjects cannot even say what “I” means.

(26.) Collapse of the old philosophy.

(27.) What unifies Hegel and his listeners lies outside of them.

(28.) The impact of a philosophy, the role it plays in the world—is no criterion of its truth.

Social-Philosophical Exercises II: Marx, Summer Semester (1931).

[Marx, Dialectic, and the Absolute] (7/2/1931).

(1.) Hegel’s dialectic is universal; one of the great problems in Marx is whether, or to what extent, dialectic is for him a universal method, a world-schema. In Capital, such a universal dialectic can only be identified so far as the attempt is made to deduce class relations, crisis, and collapse from the simple relation of exchange. Dialectic in Marx cannot be presented in the same manner as in Hegel. Even when we ask: how does universal history relate to what exists?, it is immensely difficult to come up with an answer from Marx. There’s a materialist schema for contradictions of forces and relations of production, but we know Marx was not of the conviction that he’d captured the whole world in it; not everything fits into the schema, as with Hegel. Didn’t Marx himself propose a method of research opposed to all other methods a priori, in that every other method presupposes the recognition of some absolute or other, while Marx’s dialectic doesn’t?

(2.) The problem of absoluteness, illustrated, for example, by being and consciousness. Marx thinks that when some philosopher speaks of the relation between thinking and being, he presupposes that what he’s referred to with the words “thinking” and “being” is something that, as such, remains utterly identical, independent of any subject: thinking, consciousness, being. When Aristotle asks, what is being?, he imagines he’s dealing with a being that is, as such, radically unchanging. When a philosopher takes changeability into account, it’s because he’s taken changeability for being: he thus speaks of the changeable in the same absolute mode as being itself, or, as does Aristotle, of being unchanging. Likewise for consciousness.

When Marx says that being determines consciousness, he distances himself from any absolute in a twofold sense—first, because he’s referring to a determinate period of history: we see that in each case human beings have thought what they had to due to their position in the process of production; thus, this claim is historically relative. Further, Marx is conscious of the fact that when he makes these claims, he is himself positioned within a historical situation in the last instance determined by the struggles of the proletariat against the bourgeoisie, and it’s from within this struggle that Marx attacks its idealistic conception. In this sense, his conception is relative as well. However, that doesn’t mean the claim in question is merely a half-truth; it only means that once this historical situation has passed, one cannot imagine that there is some subject, existing independently of the situation, who would remain to recognize such a claim as true. Marx put a radical end to any transcendental subjectivity. Absolute, true being would have to include an absolute subject. If there is no such subject to be found, then I must know that once I am dead, there is no sense to speak of this ‘truth.’ Truth is, for Marx himself, nothing but the agreement between the subject and an object in history. Any truth supposed to have transcendental sense in history such that the subject who knows it might say: even if I myself have passed away, it would still be true—this would only be nonsense. It can only be said: from where I stand, I cannot conceive that this proposition I speak now will, some day, no longer be true. This is not quite relative; it only means that knowledge of one’s subjectivity, and knowledge that one’s subjectivity can never be absolutely illuminated, have become part of the truth itself.

[Cont…] (7/19[?]/1931)

(1.) Is the restriction to the empirical—absolutized? No: for Marx, the empirical itself is relativized.

(2) What does absolutizing mean?

a) = Judgment that’s “valid” independent of the cognizing subject, or, better: has a meaning, signifies something, but this applies to Marx’s propositions too; Marx’s system also makes a claim to this absoluteness.

b) But there’s no sense in speaking a proposition incapable of being verified by any subject. Thus, all propositions are relative = related to a subject. The question of truth only has any sense when there are judgments, but judgment requires subjects. There is no sense in discussing a truth whose definition does not contain the problematic concept of the subject.

[Weinzieher (?):] But isn’t it a tautology to say: cognition is bound to a subject?

MH: Hegel! Fichte! But it’s an entirely different problem whether the world is dependent on subjects: but it never really is, even to the extent the subject changes the world. The illegitimate absolutizations presuppose that one is identical with a subject who is not bound to time!

[Margin: Confusion of two problems.]

Because we order our own existence according to our concept of time, I must assume there are facts that come before and after me. The question of the independence of truth to a cognizing subject is a different problem altogether! Lenin’s accusation against Mach—both problems are at stake here! All of the [x] statements about the cognition of the process itself are dull and boring. a) Historical conditionality is not equivalent to b) relativization of truth—a) and b) are completely different problems! I take it upon myself to pass judgment on whether Plato’s propositions are false.

Hasselberg: The concept of truth is never a concept of function. A sentence is not true just because its contrary cannot be proven.

MH: To the extent I cannot realize what Plato’s propositions meant, I cannot pose the question of their truth. A proposition is true when the fact I have to expect I’ll find on the basis of this proposition is actually found. The determination of its adequacy says nothing of its truth. For ex.: the angels of Thomas Aquinas—are not true.

The metaphysical obstacles to MH’s concept of truth. This concept of truth has to do with practice. In ideological terms, such judgments serve determinate social purposes but are not themselves true. True propositions might be placed within an ideological context, but in this case it is the context which is untrue. The dynamic concept of truth contains the thought that wherever there’s a person who believes in something with his entire soul, there must be some truth to it too. Thesis: “That thinking is determined through economic conditions is no Wortformel, but a determinate assertion about a determinate epoch and is, therefore, verifiable!” Lax formulations out of the need for a Weltanschauung, but this Weltanschauung doesn’t exist, only partial truths [Teilwahrheiten], etc.

[Margin: S-R]8

Determination of truth does not mean ‘empiricism’ in the sense of a reduction to sensible facts!

[Margin: Centrum of the world.]

But there is resistance to the concept of truth in the thought that one might live on the ground of some Weltanschauung with which they can push forward into the centrum of the world. This is what Scheler, Heidegger, etc. think. They believe they have grasped the structure of the world.

[Margin: Practice]

Marx, however, believes he has condensed [zusammengefasst] the propositions most important in relation to present-day practice. For Marx, ‘essential’ means that which is determinative for the practice he desires.

[Margin: Essence]

Surface and essence of things are not determined on the basis of the concept of truth, but on the basis of practice.

[Margin: Truth and Practice]

In a completely determinate historical situation, the requirements of theories etc. are determined by the practice of our subject. What does the goal have to do with the truth?

[MH:] When they achieve it: once the proletariat desires socialism not on the basis of its own interests but on the basis of truth, then they will have achieved something, which, as far as I can see, does not yet exist.

[Cont…] (7/16/1931)

(1.) The “contradiction” between forces and relations of productions as the forward-driver [das Weitertreibende].

(2.) The demands of the opponents of bourgeois society step onto the stage under the banner of ideals postulated by this society itself.

(3.) Truth is not identical with eventual truths [eventuelle Wahrheiten]; today there is a need to get from the abstract concept of truth to truth fulfilled in the process of thought.

(4.) Hasselberg: Another form of dialectic. Production = consumption; production for consumption; production = consumption.

Westermann: Object of Marx’s Theory.

(1.) Society = laboring society = the labor-process of human beings conceived as way of life.

(2.) Mode of production = way of life.

(3.) Society = a part of nature.

(4.) Capital, p. 146. Nature and man as two different things.

(5.) Society = nature and man at the same time.

Subject = Man; Object = Nature—the same.

(6.) Conditions of production are transformed from natural to historical.

(7.) To the extent man transforms nature, nature transforms itself.

(8.) Unity of human beings and nature exists in “Industry.”

(9.) Are relations of production imposed by nature?

(10.) The totality of relations of production = the economic structure of society.

(11.) Cunow on economic structure: relations of production = the sum of reciprocal relations [Wechselverhältnisse] arising from the process of production.

(12.) Relations of production are the preeminent site of reification, “mediation” between persons through things. Natural things seemingly take on social character: e.g., money! In the factory, the relation between human beings in production is a direct, technical one; in the marketplace, a relationship between human beings is only possible by mediation of the commodity.

(13.) MH: To what extent do commodities, money, etc. constitute the relation between human beings?

(14.) Relations of production must always be produced anew. “Formal provisional significance” [“Formale Vorbedeutung”] of the concept of relations of production: the position of human beings towards one another in the process of production. Property relations = expression of relations of production.

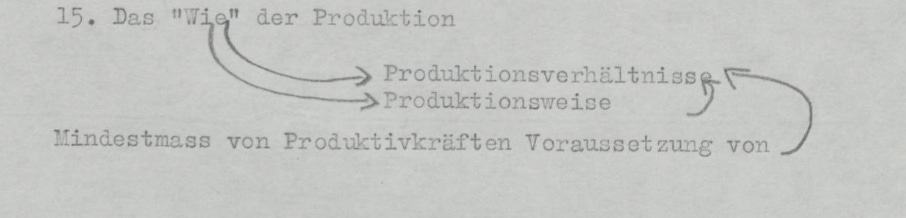

(15.) The “How” of Production

Forces of production

Not metaphysical-dogmatic, but centered around human society.

What is produced in one period can be a natural given [naturgegeben] in another (Climate in Germany).

(17.) Totality of relations of production = productive force (2nd order?)

(18.) [S-R:] Forces of production are product of society, as well as relations of production. Reciprocity?

(19.) MH: The theory of historical materialism centers on the breaking-points, on the turning-points! So, the forces of production are the primary, truly compelling moment.

(20.) Material or functional separation of the forces from the relations of production. The same man can be viewed from different perspectives: (1) as member of a determinate class; (2) as part of the productive-labor force of the revolutionary class.

(21.) Relations of production relatively static; conflict is possible in principle.

[Margin: Immanent goal of history, hence “prehistory” of humanity; what is meant: immanent tendencies!]

(22.) Hegel actually sought to construct the living process, to capture it completely. Marx does not; he lacks the identity: subject-object. With the abstract concept derived from analysis of the process, it might be possible to reflect the process, but not reconstruct it in its totality. It is easy to construct the living using concepts derived from the living!

[Cont…] (7/23/1931)

(1.) Concept of the forces of production is no conclusive [abschließender] concept.

(2.) Forces and relations of production are no ideal-typical concepts.

(3.) Forces of production can also be understood as ‘human drives.’

[Sevenich:] Marx’s economic conception.

(1) Significance of Marx’s economic conception for his system as a whole.

(2) ‘Being’ in Marx’s philosophy of history—not economic theory; ‘Being’ is the intensification [Intensivierung] of history in the struggle between the two classes. (Tendencies = biological laws of nature, which can be established by economic analysis, mean nothing but the fact that society develops in a determinate direction = dynamic structure.)

Mechanism. (Accusation of mechanism leveled against enlightenment and classical economics: all events are to be explained on the basis of partial conditions [Teilbedingungen]. But Hegel demonstrated that something can be brought about by partial conditions which subsequently develops a lawfulness of its own, different from that of the conditions under which it was brought about: e.g., society, human life, etc.)

After the conclusion of prehistory, human history will no longer be capable of being explained by biological laws.

[Margin: After the conclusion of prehistory. Subject of society.]

We would only be able to speak of society-as-subject with the conclusion of prehistory, once society consciously conducts its metabolism with nature.

(3) Process of the becoming-conscious of humanity in the proletariat.9

MH: Through becoming-conscious of the conditions with recourse to which class-society can be abandoned.

(4) The revolution is not just another stage of history, but a culmination-point of universal-historical significance: world-historical interpretive schema.

(MH: One must respond to this quite brutally. Certainly, Marx is often interpreted in this way.)

Marx would have said:

(1) What ‘universal history’ is, I know not. I know only the history of class struggle.

(2) What will happen in the revolution: things will be different, human beings will no longer be exploited, will no longer need to go hungry, will no longer be butchered for the sake of profit, etc.

(3) The class which experiences this material misery has an interest in abandoning the class domination it is subject to.

(4) Thus, class domination must be abandoned altogether! (?)

(This has nothing of the value-accent of ‘humanity,’ ‘universal history.’)

(5) For Marx, there is no existence—in the sense of what is living—other than that of the individual human being.

(6) The principles of dividing history into periods are made by human beings themselves. Marx should not be interpreted with concepts which have no meaning in a materialist conception of history.

(7) History is nothing but the continuity of the struggles human beings have with one another. The recognition of the division of human beings according to class cannot be compelled by logical means; for this division is given through the position of the struggling proletariat. Whenever someone divides history into periods according to philosophy, there is no way to determine whether they are lying. Whenever someone adopts the position of a determinate practice and seeks to accomplish determinate goals, they must describe this practice in such a way that the concepts can be used by those who come after; for example, a doctor who wishes to heal the sick will describe the human being differently from the practitioner of Schelerian anthropology—and neither of them needs to be a liar for this to be true!

Sevenich: Points out to the value-accent, which refers to the inhumanity of the proletariat and, through the mechanism of reification, to the bourgeoisie as well.

MH: What is the meaning of these evaluations for Marx? Solidarity with the proletariat.

MH: Against the philosophization [Verphilosophierung] of Marxism. Marx was a materialist, and therefore did not believe it was possible to justify a stance [Haltung] on rational grounds, but rather that these rational grounds were themselves to be explained. As long as one speaks of tendencies and structures, they remain firmly within the sphere of scientific explanations.

(5) “Self-guarantee of Marxism” (Carl Schmitt)—because it is scientific?

(6) Metaphysical dialectics transformed into real dialectics. (Hegel at the end of history. Marx: positions himself outside of the social struggle by explaining it.)

(7) Contra Kelsen’s ‘proof’ that society and state ‘come apart’ [auseinanderfallen]: Marx doesn’t need to say anything more about classless society than the fact it is classless, but this says nothing against him.

(8) Marx says nothing about the essence [Wesen] of the proletariat; proletariat as bearer of humanity and its inhuman situation.

(Marx demanded that the slogans that were mere ideology in bourgeois society be realized!)

“Freedom” for Marx.

(1.) Adopted from the bourgeois demand: unfolding of certain abilities, exercise of certain powers, etc. Possibility of unfolding the “abilities” [“Anlagen”] of the individual. Adopted from the revolutionary epoch of liberal theory: the happiness of the individual, greater pleasure and lesser displeasure! He proves that the assertion that these things are fulfilled in the bourgeois system is ideology. He measures the bourgeois order according to its own principles and actually carries their demands through. But all must be investigated scientifically. These concepts are adopted as demands of human beings according to determinate earthly conditions. But this system has a tendency within itself to fail to fulfill even the most basic demands. This is why it is so crucial to identify these tendencies, because this makes it possible that a peaceful and secure life is already possible on the basis of technical progress alone, etc. Marx’s fear is not that human beings will become bourgeois [verspiessern], but that they have no opportunity to do so!

Sevenich: Marx’s Economic Theory.

[Margin: Totality of relations of production.]

(1.) “Being” and “social” being.

(2.) “Society” for Marx: a) mutual relation and function; b) socially necessary = balance of mean, average, normal? c) relations of production = economic structure of society, power [Mächtigkeit] expressing itself as society, according to which human beings are ordered.

(3.) Production = economy? (Understanding value-theory on this basis.)

(4.) Man and nature mediated through the natural property of labor.

(5.) Economy autonomous … [re:] superstructure.

(6.) Money capital, etc. = functional forms of capital, economic character-masks of human being.

(7.) Economic dynamics as primary.

(8.) Pariah class: proletariat = dissolution of society as particular social class [Stand]! —So: society no longer multi-dimensional [Vielschichtigkeit], but polarity?

(9.) Class = uniform mass.

(10.) Stratification of the bourgeoisie—especially that of the proletariat. For Marxism, unacceptable.

(11.) Question of the human being: strongest force of production = revolutionary class itself.

(12.) Maturity: “Humanity” only sets tasks for itself it can solve.

(13) Human = a) quantitative element in the process of production (bearer of labor, part of society); b) = idea of human being.

Wanz: Law of value = special case of commodity production. Law of value = determination of the appearance and magnitude of exchange-value.

Doppler: Against autonomy of economy.

MH: Supplement to Doppler: Marx is no philosopher of identity; he does not want to pass a final determination about the essence of human beings.

Key position of the economic.

If human beings want to live, then they will have to acquire their means of subsistence from nature. In the commodity-economy, production and reproduction become dependent upon the laws of the market. If one learns how to comprehend the laws according to which production and exchange occur, then they will also comprehend the events which occur in a society of struggle. Law of value: capitalist form, relative eternity of content.

Dörter: Reciprocity and the overarching moment. One can change small details here and there, but cannot abolish the crises—hence the possibility of making projections, but without any apodicticity.

Hasselberg: Correspondence = essence and appearance (superstructure—substructure, etc.). Hasselberg disputes this: in the first place, the analogy can only be understood if we introduce certain notions from the psychology of human beings and then understand them in causal terms. In principle, it must be possible to demonstrate all of the mediating links.

MH: Necessity in the strict, mathematical sense does not exist in society!

Dörter: Against universal character. The concept from the presentation by Ms. S. (?): in the presentation, the issue of ‘labor’ was raised from the superstructure and the economic moment was presupposed! For Marx, this would be a philosophical postulate. What is typically understood by ‘ontology’: viz., that human beings are free!

The distinction between capitalist and socialist economies lies in the fact that in the former, catastrophes are the only reliable result; in the latter, the economy can be calculated to generate results human beings desire!

Regarding Marx’s materialism and its logical presuppositions. According to Marx, there is no foothold in the infinite. There is nothing but a real process, and the thoughts of human beings who come into being and pass away in its course, just like other realities.

‘Radical thinking’ for Marx doesn’t mean the same thing as posing radical philosophical questions, but getting to the root of things. What is ideological is often not the lie or the reinterpretation, but in preoccupation with a wholly determinate object.

Sevenich: Problem of the synthesis of Hegelian dialectics and positivist causality. What have the latter adopted from the German, and what does this mean for dialectics and for positivism.

MH: This question is not decisive for me—because knowing as such is not what is most important to me! This difference of attitude manifests as a difference of attitude!

[Seminar von Professor Horkheimer, über “Geschichtsphilosophie.” Sitzung vom 4.XIII.30] In: MHA Na [618], S. [140]-[142].

“Sozialphilosophische Übungen. Horkheimer-Seminar, Sommer-Semester 1931.” In: Na 619 [link], S. [1]-[13].

[Reference in original: “(Kap. III/ II [or L1?] / S. 355).”]

[menschenwürdiges Dasein der Menschen]

[Darstellung fällt mit Begründung zusammen.]

“Solm-Rethel.”

[Prozess des Bewusstwerdens der Menschheit im Proletariat]