Notes: Towards a Reconstruction of the 'Dialectic,' Part 2.

3 Guidelines + 2 Tasks for future research.

Other posts in this series:

Teaser: The Rapid Deactivation of the Subject (1944/45). From the Horkheimer-Adorno correspondence. (+ a speculative 'Memo').

[Collection:] MAX HORKHEIMER: PHILOSOPHICAL PARERGA (1945-1949). Fragments on the fate of the late subjects of late capitalism.

Translation: Letters on the Problem of Prehistory (48/49). Two excerpts on Marx from Adorno and Horkheimer's correspondence.

Collection: “First Must the Site Be Cleared” (1945-1949). Adorno & Horkheimer's speculative digressions for Part 2 of the ‘Dialectic.’

Thesis: Adorno and Horkheimer began the process of composing the ‘second part’ of their Dialectics-project in 1944/45 following the pattern they established for Dialectic of Enlightenment:

Generating and gathering a ‘pool’ of notes in different formats—ideas introduced in Diskussionsprotokolle, digressions in letters, ‘aphorisms’ with more conscious stylistic form, etc.

Identifying central themes around which their notes ‘cluster,’ particularly by reflecting on their own recurring concerns. Thematic clusters (‘rackets,’ ‘dialectical logic,’ etc) progressively coalesce into a broader thematic ‘complex.’

Isolating a ‘crystallization-point’ for their collaborative essay-writing, from which perspective the ‘pool of notes’ and ‘complex of clusters’ becomes a constellation through which different critical models are launched to variable effect.

Conception of ‘the second part’ (Summer 1944).

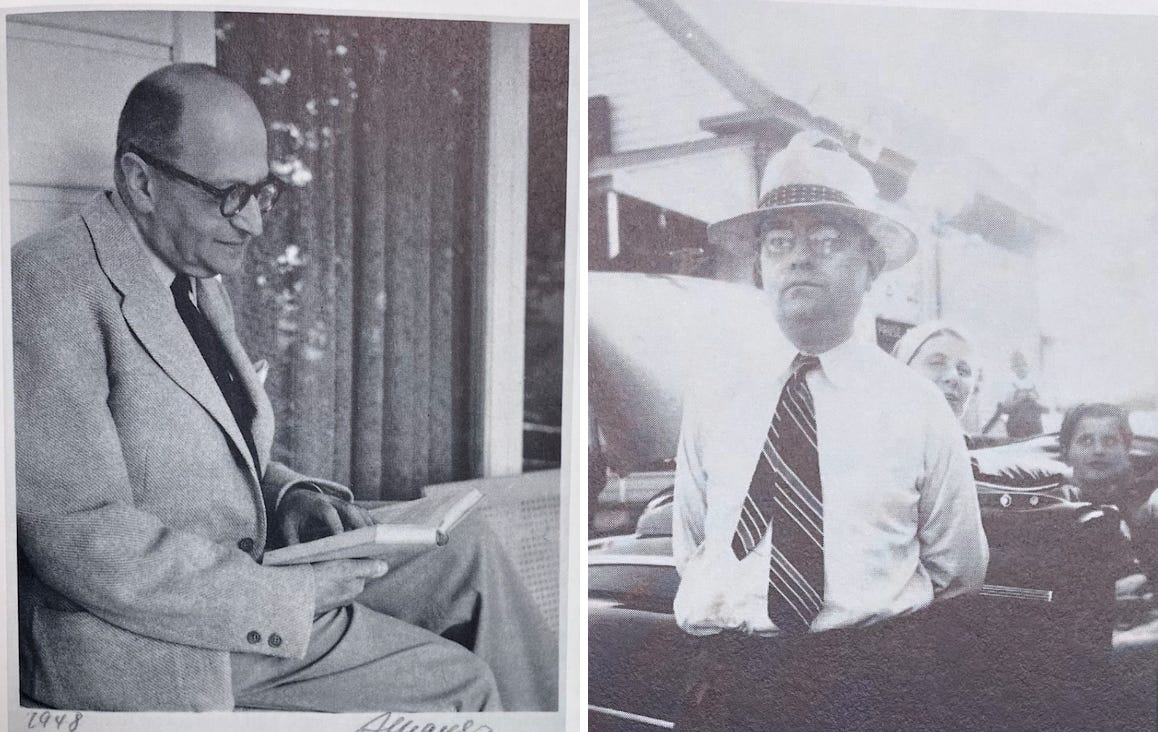

With the exception of Thesis VII of “Elements of Anti-Semitism”—which Adorno and Horkheimer would write in collaboration with Leo Löwenthal (and Paul Massing) in the summer of 1946 (see: excerpts from the debate about Thesis VII here)—the book that would be published under the title Dialektik der Aufklärung by Querido Verlag in Amsterdam in 1947 was almost entirely written before the earliest textual variant of the book, the Philosophische Fragmente, was printed as a limited-run mimeograph in three editions, the first for Pollock’s 50th birthday on 5/22/1944 and the subsequent editions for others in their intellectual circles later that same fall. In his research on “The Making and the Marketing of the Philosophische Fragmente” (2017), James Schmidt discovered a letter from Horkheimer to Löwenthal on June 14th, 1944, in which Horkheimer asks for Löwenthal’s notes for revision of the manuscript of the Fragmente (Löwenthal was the ISR’s in-house editor and censor through the 1940s), remarking in passing that he is glad Löwenthal liked the book but hopes “that the second part will still be much better.”1 This means that Adorno and Horkheimer’s plans for a ‘second part’ of their Dialectic had already begun to take shape less than a month after their first printing of the Fragmente for Pollock’s 50th birthday. The significance of Schmidt’s discovery for reconstructing ‘the second part’ is that it enables us to generate our first guideline for further research in Adorno and Horkheimer’s correspondence:

Guideline 1: Whenever Horkheimer and Adorno mention the continuation of their Dialectic in correspondence after June 1944, unless their objective has been specified as making revisions/additions to the Fragmente (such as their work on thesis VII of “Elements” in Summer 1946), this should be interpreted as a reference to the projected ‘second part.’

A New ‘Pool’ of Fragments (1945-).

In the course of writing the Fragmente, a process which began with several Diskussionsprotokolle (e.g., “The Temporal Core of Truth. Experience and Utopia in Dialectical Theory.”) in the fall of 1939 and ended with the finishing touches made to the manuscript of the Fragmente before the printing the Festschrift edition for Pollock in May 1944, Adorno and Horkheimer developed a pattern which seems to have served as a model for the composition of the ‘second part’ as well. In addition to conducting a new series of Diskussionsprotokolle for ‘the second part’ of the Dialectic in October 1946 with Adorno—posthumously published under the title “Rettung der Aufklärung. Diskussion über eine geplante Schrift zur Dialektik” in Horkheimer’s Gesammelte Schriften, Band 12 (1985) (translation forthcoming)—Horkheimer also began to generate a ‘pool’ of notes for his ongoing collaboration with Adorno in response to Adorno’s own continuation of their interrupted work in Minima Moralia. (I’ve begun to outline the multi-stage process in which Horkheimer began collecting a ‘pool’ of fragments, which he and Adorno subjected to various degrees of revision and from out of which they would draw the “Notes and Sketches” for the final chapter of the 1944 Fragmente, in a note here.)

In October 1944, Adorno writes a letter to his parents about Horkheimer’s imminent departure for New York after accepting the position of research director for the scientific department of the American Jewish Committee, describing the success as bittersweet because it means “[t]he interruption of our big study[, which] is equally painful to both of us and we are quite determined not to drop it, even if the world does God knows what to support us.”2 In October 1945, Adorno writes his parents that Horkheimer had finally returned from his year in New York, and writes of his excitement that they finally have the opportunity to resume their real task together, and for which Minima Moralia (he had recently finished part II) was written as preparation:

There is nothing mysterious about my workload here; sometimes it is simply difficult at this distance, if one is not spending every day together, to convey an impression of everyday events. It is simply that I have to devote myself very energetically to the two Berkeley projects, at the same time as having spent all my energy keeping the theoretical work going that was interrupted for a year through Max’s departure to New York, so that not only can we pick up where we left off, but also I will have made serious progress during that year. I think I have succeeded on that count, in the form of a very long manuscript written in the Nietzschean aphoristic form, relating to a relatively wide range of philosophical objects, but above all the question of what has fundamentally become of ‘life’ under the conditions of monopoly capitalism. Max returned on Monday after an evidently very successful stay in New York, but is horribly exhausted. […] The Jewish matters are continuing, but we are determined to organize them so that we do not spend our most productive years on things that, after all, are only of peripheral interest to us.3

What Adorno does not mention in the letter is that Horkheimer had also made an effort to continue their interrupted theoretical work in the rare moments of quiet—in the first weeks of January 1945, just as Adorno was putting the finishing touches on the first part of Minima Moralia as a surprise for Horkheimer on the occasion of his 50th birthday on February 14th,4 Horkheimer was writing Adorno (1/11/1945) ironic memoranda from his desk at 3AM containing reflections on how they might continue the dialectical logic they’d begun in the Fragmente and meditations on the connection between the dialectic of enlightenment and the construction and lighting of skyscrapers as he stared out of his office windows across from 432 Fourth Avenue. In reply, Adorno says he is happy to accept the aphorisms “as a sound basis for future memoranda.” (II. Memorandum To: Dr. T.W.A., N.I.L.P.F. From: Dr. M.H., M.A.M.U., 1/11/1945.) Having finished reading the first part of Minima Moralia later that spring, Horkheimer responds in kind: “I am happy with the Minima Moralia. They lay out a bridge to our future. Hopefully the shore is not much farther.”5

In 1947, Horkheimer assigns the title Philosophical Parerga to a possible collection of these seemingly miscellaneous notes that, for whatever reason, “did not go into the Fragmente.” The implication, of course, is that they could have. In a previous post on this blog, I’ve published translations of five fragments Horkheimer wrote during his stint in New York between winter and fall 1945. There is reason to read these as part of Horkheimer’s ongoing philosophical collaboration with Adorno as well. There is an internal system of references that connects their correspondence (‘The rapid deactivation of the subject’ (Nov. 1944-Jan. 1945)) and Horkheimer’s Parerga on the fate of the late subjects of late capitalist society—for instance, in an early 1945 fragment titled Sociological Distinctions, Horkheimer develops a criticism of the over-qualification and domestication of the category of class by American sociologists, an issue Adorno had just recently raised in a letter to Horkheimer from late December 1944 (see: Adorno to Horkheimer, 12/21/1944.) and with which both Adorno and Horkheimer had long been preoccupied.

In fact, there are a handful of fragments in the Max-Horkheimer-Archiv [MHA], posthumously published in MHGS, Bd. 12 (1985), dated “October 1946” (e.g., “Towards a Critique of the American Social Sciences”; “The Fate of Revolutionary Movements”). If accurate, this would mean these fragments were at the very least written around the same time as Adorno and Horkheimer’s Diskussionsprotokolle, four of which have survived (dated: 10/3, 10/7, 10/10, 10/14). Strong thematic connections between these “October 1946” fragments and the Diskussionsprotokolle recorded during the first two weeks of that same month seem to suggest the coincidence is more than accidental.

Finally, some notes written later in the 1940s—such as Horkheimer’s “On the powerlessness of the individual and the autonomizing of power in the economy of capitalism (10/18/1949),” which Horkheimer excerpts from a letter to Löwenthal, and Adorno’s comment “On Marx’s Concept of Prehistory,” from a letter to Horkheimer written around the same time (7/2/1949)—explicitly refer to parts of the Dialectic of Enlightenment (1947) they consider particularly important as a foundation for further theoretical developments—in these, Horkheimer and Adorno each refer to the fragment from “Notes and Sketches” titled “Critique of the Philosophy of History.” Occasionally, they will even ‘tag’ certain ‘theoretical’ reflections in passing as possible paths to reaching self-enlightened enlightenment (cf. Horkheimer to Löwenthal, 11/23/1948, on the problem of “prehistory” and “the concept of restored enlightenment”).

Altogether, these considerations enable us to generate a second guideline for researching ‘the second part’ of the Dialectic:

Guideline 2: Horkheimer’s seemingly ‘miscellaneous’ notes written after January 1945 may be read as sporadic contributions to the ‘resumption’ of his interrupted philosophical collaboration with Adorno, in parallel to Adorno’s own more substantial contributions to this end as he finished the first part of Minima Moralia and began to work on the second.

The Open-Ended Horizon of the Dialectic (ca. 1935-1950).

On the basis of my research, I have come to believe that past interpreters of the ‘first generation of the Frankfurt School,’ and of Adorno and Horkheimer’s 1940s work in particular, have not distinguished between their work on the Philosophische Fragmente (1939-1944) and their work on ‘the second part’ of the Dialectic for two important reasons.

First, the manuscript that would be published under the title Dialektik der Aufklärung in 1947 was still titled the Fragmente at the very least through December 1946, and until some point in the revision of the manuscript in 1947, any reference in Adorno and Horkheimer’s correspondence to the “Dialektik der Aufklärung” would have actually been a reference to the first chapter of the Fragmente, which was only re-titled “Begriff der Aufklärung” [“The Concept of Enlightenment”] at the same time the book itself was re-titled Dialektik der Aufklärung in the spring/summer months of 1947.6 This makes it difficult to track what Adorno and Horkheimer did and did not consider notes for the book that would be published in 1947 as Dialectic of Enlightenment. However, as noted above, Adorno and Horkheimer had finished nearly the entirety of the manuscript of the book by May 1944, and would return to the manuscript in mid-1946 only to make cuts and revise the language of the Fragmente for ‘tactical’ reasons (such as their late elimination of most of their uses of the word ‘monopoly’ in response to a news story about red-baiting) and to write and discuss revisions for the sole significant addition to the text after fall 1944: Thesis VII of “Elements of Anti-Semitism.”

Second, there is the added complication that Adorno and Horkheimer would often refer to ‘the Dialectic’ in their letters after June 1944 not only in reference to the first chapter of the Fragmente but, perplexingly, to the project of the Dialectic in the sense they had nebulously invoked throughout their correspondence since the mid-1930s. It is in this latter sense that Horkheimer refers to plans for ‘the Dialectic’ when discussing potential collaboration on the project with Karl Korsch (1938/39) or writing to Adolph Lowe in a letter of November 1938 that he had “begun the preparatory work for the book on dialectical philosophy.” As early as February 1935, Adorno writes Horkheimer about “our actual and common theoretical task: namely, the dialectical logic,”7 and again in May 1936 about “our major work” in discovering “the exact turning-points [Umschlagstellen] into materialistic dialectics” through an (immanent) “critique of idealistic errors in the strictest sense.”8 At one time, the Dialectic was to incorporate Adorno’s Husserlkritik as a prolegomena to dialectical materialism by way of the determinate negation of the most sophisticated ‘undialectical’ idealism of the day; at another, the Dialectic was to prominently feature dialogues co-authored with Korsch about contemporary impasses in political thought from a libertarian communist perspective à la Hobbes’ Dialogue between a Philosopher and a Student of the Common Laws of England (1681) and/or de Maistre’s Soirées de St. Petersbourg (1821).

The open-endedness of Adorno and Horkheimer’s conception of the Dialectic is apparent from a letter Horkheimer writes to Paul Tillich in 1924, in reply to the latter’s critique of “Vernunft und Selbsterhaltung” (1942).9 Horkheimer had written this essay in intensive collaboration with Adorno over the course of several months in 1941, and Adorno is even named as co-author on several early drafts of the manuscript.10 Horkheimer’s reply to Tillich is therefore not only a defense of his own essay, but also of his collaboration with Adorno and their shared conception of their project:

I’ve only been able to say for the past two months that we’ve been working on the actual text [of the Dialektik]. Before that the whole time passed with preliminary research and other tasks, none of which I regret. A considerable number of preliminary notes already exist. Nonetheless, their final formulation will probably still take a few years. This is due in part to the objective difficulty of the task, that is, producing a formulation of dialectical philosophy that does justice to the experience of recent decades, in part to our lack of routine, the cumbersomeness of thinking, and the continual lack of clarity about important points. For God's sake, just don’t promise yourself a magnificent result; at the end, nothing more will emerge other than a kind of protocol of our thoughts that have been known to you for a long time. All the same, you’ll say that all of it was much better formulated in the discussions of one or another sect of the fourth or fifth century. In spite of that, the work fulfills the need to see somewhat more clearly before the probably imminent decline and to leave behind something that could have some meaning for someone.11

In this passage, Horkheimer frames the project of the Dialectic as an open-ended one with two desiderata: first, formulating “a dialectical philosophy that does justice to the experience of recent decades”; second, arriving at a final, clearer formulation of the ideas contained in “[a] considerable number of preliminary notes” already written, a task which “will probably still take a few years.” These desiderata open a horizon for the broader project of the Dialectic that extends well past both the mimeograph of the Fragmente in 1944 and the publication of Dialektik der Aufklärung in 1947. As I will argue in a future post, this horizon closes around 1950. In The Frankfurt School (1994), Rolf Wiggershaus notes that Adorno expresses his fears in several letters written during the ISR’s ‘return’ to West Germany in 1949/50 that Horkheimer’s new focus on institutional politics for the Institute would ultimately deprive him of the “opportunity to take part in their joint philosophical work.”12 These fears would prove well-founded.

Given the variable scope of the Dialectic project between 1935 and 1950, we can generate a third guideline for research into the continuation of the Dialectic:

Guideline 3: Whenever Horkheimer and Adorno mention the continuation of their Dialectic in their correspondence after May/June 1944, unless they specify “Dialektik der Aufklärung,” the title of the first chapter of the Fragmente until it would become the name of the book itself in mid-1947, they are referring to their broader project of the Dialectic of which Dialectic of Enlightenment was itself only a part, contextualized within an open-ended horizon of collaboration—to develop their own past fragmentary notes in the service of a comprehensive dialectical philosophy capable of doing the social upheavals of ‘recent decades’ justice—that closed around 1950.

First Task for Conceptual Reconstruction: Identifying Thematic Clusters of Notes.

Following the above guidelines, I have been able to identify several thematic clusters of notes for ‘the second part’ of the Dialectic in their correspondence between June 1944 and December 1949. A few clusters are more obvious than others—for example, the excerpts I’ve collected from their exchange the concept of compassion in moral philosophy in 1949 (IV. Letters: Remarks on the Tat Twam Asi (1949).), which is a focused discussion on a single theme that lasts for several weeks (late May through mid-June 1949) and is ultimately set aside (or momentarily tabled) for future work on “the task of our philosophy,” as Adorno calls it. Exchanges like this are rare. More often, thematic clusters arise as Adorno and Horkheimer repeatedly turn back to shared theoretical concerns in letters sometimes separated by months or even years. These clusters often include correspondence with other collaborators. For instance, Horkheimer writes Löwenthal about his plans to write “an immanent critique of psychology” in August 1948 (Letter: Spontaneity contra Psychology (8/30/1948).), then again to Marcuse about how he’s been making preparations for a “fundamental critique of psychology” in December 1948.13 By May 1949, Horkheimer and Adorno are exchanging letters on the limitations of any “immanent” or “fundamental” critique of psychology given its diminishing importance as an autonomous discipline in postwar social science and postwar society (Horkheimer—Letter: The Total Concept of Society (5/8/1949); Adorno—Letter: The Concept of Total Socialization (5/19/1949)).

Accordingly, I argue that thematic clusters of notes can be identified by repetition and variation on shared thematic concerns which are ‘tagged’ as subjects for future theoretical collaboration in Adorno and Horkheimer’s correspondence—with each other and with others—between summer 1944 and December 1949. Two examples:

Adorno and Horkheimer make vague reference to the continuation of “our own work” and their excitement at the prospect of being able “to delve back into these matters with [one another] soon” in their discussions of memoranda on the subject of the Urgeschichte of anti-Semitism, Jewish character, and Jewish theology as early as spring and summer 1945 (I. Memoranda: On The Jews and Prehistory (1945)).

In letters with Adorno and other collaborators (Marcuse and Löwenthal) throughout 1948 and 1949, Horkheimer repeatedly returns to prospects for an immanent criticism of psychology, only to decide, given his ongoing discussions with Adorno, that the postwar integration of psychology into the social sciences, and sociology’s integration into the academy proper, demands a more fundamental critique of the total concept of society which underlies both sociology and social philosophy instead (III. Letters: From the Critique of Psychology to the Critique of Total Society (1948/49)).

Furthermore, because of the intertextual nature of Adorno and Horkheimer’s writing process, notes belonging to one ‘cluster’ will often contain references to other ‘clusters’—whether these other clusters are designated by specific thematic concerns, such as when Adorno ‘tags’ Horkheimer’s memo on the oath for future work on “the whole dialectic of morality” (Re: the Oath and the Dialectic of Morality), or by reference to broader projects, such as when Adorno ‘tags’ his own memo on his conversation with Anton Lourié as containing material for “our dialectical logic” (Memorandum On a Conversation with Anton Lourié (9/26/1945)).

Second Task for Conceptual Reconstruction: Isolating a Crystallization-Point.

The identification of thematic clusters of notes is only the first step, however. Commentators have taken to calling the constellation of themes for the planned ‘second part’ of the Dialectic by the name of ‘the Rettung,’ a shorthand derived from the October 1946 Diskussionsprotokolle:

[Horkheimer:] We see this moment of unity (in the analysis of politics and philosophy) in holding fast to the radical impulses of Marxism and, in fact, of the entire Enlightenment—for the rescue of the Enlightenment [Rettung der Aufklärung] is our concern—but without identifying ourselves with any empirically existing group. Our position is, in a sense, a materialism which dispenses with the prejudice of regarding any moment of existing material reality as directly positive. The paradox, the dialectical secret of a true politics, consists in choosing a critical standpoint which does not hypostatize itself as the positive standpoint.14

However, Horkheimer himself refers to the ‘second part’ in the vaguest of terms. In December 1945, Horkheimer writes a letter to Pollock lamenting that he’s had to spend so much time on the manuscript for Eclipse, “the English exoteric version of thoughts already formulated,” when what truly matters is: “the development of a positive dialectical doctrine which has not yet been written.”15 Again in March 1946, Horkheimer writes Pollock:

I am very happy about this possibility of publishing the Fragments in Europe. Just out of principle I will think it over during the next few days and then send you a wire, but I do not have any doubt that I shall accept. The Fragmente are the first part of the theory to which all of my labor-power shall be devoted in the future. The second part, which will deal with logical and, thus even more difficult questions than the first, will nevertheless be simpler, for everything has become so much clearer in the meantime. I only hope that external things will soon be put in order so that the innumerable delays will stop.16

In reply to Adolph Lowe’s praise of the way in which “the positive underground of oft-maligned negativism […] shines forth” from the last chapter of the Dialectic of Enlightenment “with great clarity” in a letter dated August 12th, 1947,17 Horkheimer affirms Lowe’s intuition of the ‘positive underground’ in his response dated August 20th:

Every other free minute I spend working on the second part of the Fragmente either with Teddie or preparing for the next day's work. As you know, this part of our studies will be devoted to a positive theory of dialectics. We have started with the most difficult part of it, the Concept of Truth.18

To the best of my knowledge, this is the closest Horkheimer comes in his correspondence to identifying the ‘crystallization-point’ around which the thematic clusters of the ‘second part’ of the Dialectic are supposed to gather into a constellation: the Concept of Truth. (By comparison, the crystallization-point for Dialectic of Enlightenment that enabled Horkheimer and Adorno to articulate an order out of the chaos of their ‘pool’ of notes was the problem of anti-Semitism. I will write more about this in a later post.) The importance of ‘the Concept of Truth’ for a new point of departure to organize their thoughts on ‘the second part’ is confirmed by Horkheimer’s exchange with Tillich, which begins with a letter from later that same month, dated August 29th, 1947:

It is a great pity that I can not discuss your impressions concerning ECLIPSE in detail right now. Your criticisms would be [all] the more valuable because Teddie and I are now engaged in writing the second part of the “Black Manuscript.” The first part is on the presses in Holland and will be published under the name Dialektik der Aufklärung before Christmas. During the last weeks we have been writing on the concept of Truth, but we are still in the beginning. Even though it is clear that your own viewpoint represented in our discussions as distinctly as it can be without your being present, I miss our regular meetings, particularly during this part of our work. Yet if you can spare a few minutes at any time, you could render us an invaluable service by telling us where we could find competent theoretical interpretations of the words of Jesus “I am the Truth.” Has this word been a subject of lively arguments and implications in Protestant or even scholastic or patriatic doctrine, and where could we find an account of them?19

Tillich is obliging in his reply from early September 1947, and while I have not yet been able to determine whether Horkheimer and Adorno incorporated his thoughtful response into their work on “the second part of the ‘Black Manuscript,’” I’ve translated the relevant part of Tillich’s reply, as it sheds light on what their conversations on ‘the second part’ may have involved in late 1947:

The idea of “aletheia” plays a major role in the entire Gospel of John. I believe I have a monograph by Prof. Fr. Büchsel on the idea of truth in the 4th Gospel (in New York). Hans von Soden has written an excellent monograph on the idea of truth in the Old and New Testaments. The best commentary on the Gospel of John is by Walter Bauer (in every theological library, e.g., Seminary in Berkeley). The most recent major work on the 4th Gospel is by R. Bultmann, but, as far as we know, there is only one copy in the country and it is not available. According to reports, it is to be the new standard-work. It traces the most important of the 12 sources back to a Syrian-Gnostic tradition. In the Gospel of John there are not only phrases such as “I am the truth” [“Ich bin die Wahrheit”], but also “being of the truth” [“Aus der Wahrheit sein”], “the truth be done” [“die Wahrheit tun”], “bearing witness to the truth” [“von der Wahrheit zeugen”], “full of grace and truth” [“voller Gnade und Wahrheit”]. All of this probably displays, like the entire Gnostic, i.e. late-antiquity syncretistic movement, a fusion of Jewish and Greek ideas of truth. The Greek concept of alethes means the unconcealed [unverborgen] and refers to the true, inalterable being [das wahre, unveränderliche Sein], the Hebrew concept of le’ amīn means to be sure, trust (the word ‘amen’ = certainly [gewißlich], has the same root [Stamm]). It always refers to human or divine steadfastness [Zuverlässigkeit] in the fulfillment of goals, promises, in short, that which remains the same as itself [das sich-selbst-gleich-bleiben], on which everything which can be trusted can itself be grounded. To be the truth, then, means to represent the true being [das wahre Sein repräsentieren], upon which one can rely and on account of whose essence [Wesen] one should act. This true essence becomes history [dieses wahre Wesen ist Geschichte geworden] (as we most appropriately translate from the Greek: sarx egeneto). One finds the truth not through penetrating into ontological layers of being [Seinsschichten], but by “seeing” the glory (doxa) of a historical phenomenon. And one only sees this doxa if one acts according to its essence (truth be done); and lastly: one can only do thusly if one stems from the true being (is of the truth). This seems to me (in a first attempt) to be what is essential to the Johannine idea of truth (which of course has nothing to do with statements made by the “historical” Jesus).20

While I am still working through Adorno’s correspondence, what I’ve found thus far is similarly—and remarkably—vague. In a letter to his parents, Adorno refers to the coming day of work, January 13th, 1947, as a “solemn day,” since “Max and I are starting a big piece of work together.”21 Likewise, just over two years later, in a letter to Adorno’s parents dated January 20th, 1949, Gretel Adorno writes: “On four afternoons every week, Teddie works with Max on the follow-up to their big text.”22 The most specific reference I’ve found Adorno make to the continuation of their work is in a letter from September 1947, in which he writes that he’s returned to their shared task to rethink the concept of the materialist dialectic in his confrontation with Hegel during recent studies of the Phenomenology of Spirit.23

Horkheimer to Löwenthal, 6/14/1944. In: Max-Horkheimer-Archiv [MHA] Na [543], S. [79] 56.

James Schmidt (2017): “Plans for the distribution of the Fragmente proceeded apace into June. By the middle of the month, Lowenthal had completed a review of the manuscript and sent Horkheimer an enthusiastic, albeit somewhat enigmatic, telegram praising the work. Horkheimer responded on June 14 with a lengthy letter that began by observing, “it is a fine thing that you like the book and I hope that the second part will still be much better.“ The “second part” would appear to be a reference to the projected, but never completed, sequel, which would carry out the formidable task of explaining how enlightenment might be rescued from the catastrophe that had befallen it. That Horkheimer speaks of a “second part” of the book, rather than a “second book” is consistent with a somewhat enigmatic passage in the 1944 preface (which was removed from the 1947 version) stating: “If the good fortune of being able to work on such questions without the unpleasant pressure of immediate purposes should continue, we hope to complete the whole work in the not too distant future. …” This passage should serve as a reminder that Philosophische Fragmente was regarded by its authors as an incomplete work, requiring further elaboration before it could take its place among more conventionally published works. We know, from one of Adorno’s letters to his parents that, sometime before the beginning of May 1944, Querido Verlag accepted the Fragmente for publication. It is conceivable that Horkheimer and Adorno had (at least initially) intended for this projected revised version to incorporate the promised “second part.” But what would eventually be published in 1947 consisted of a revised version of the 1944 edition that adopted somewhat more circumspect language and eliminated the confessions of its incompleteness but did not provide an explanation of how the “rescue of enlightenment” might be effected.” In: “The Making and the Marketing of the Philosophische Fragmente: A Note on the Early History of the Dialectic of Enlightenment (Part I)” (1/19/2017) [link]

Adorno to his Parents, 10/12/1944: “As far as Max’s position is concerned, he will remain director of the institute, but his salary will be paid by the American Jewish Committee. They have meanwhile accepted the first of the research projects we sent them, and I am co-director of this part-project with a certain Professor Sanford from Berkeley University (in San Francisco). Maidon will be going to New York at the end of November and stay there until spring, but then return here—we are all retaining our residences here. Although the whole development is a great personal success for Max, and I may say also for me, he is by no means leaving happily, but genuinely out of a certain sense of responsibility. The interruption of our big study is equally painful to both of us and we are quite determined not to drop it, even if the world does God knows what to support us. Max will probably leave next week, and I will go to San Francisco for a week directly after that to organize the new project there.” In: Letters to His Parents, 1939-1951. Edited by Christoph Gödde and Henri Lonitz, translated by Wieland Hoban. (Polity, 2006), 199.

Adorno to his Parents, 10/31/1945. In: Ibid., 235-236.

Adorno to his Parents, 1/12/1945: “I believe I wrote to you that I had completed a major philosophical text, (Ed. Fn. 4. This refers to Minima Moralia.) but this is top secret, especially as far as Max is concerned, as it is to be a surprise for his 50th birthday.” In: Ibid., 212-213.

Cf. Adorno’s ‘Dedication’ to Minima Moralia [1951]: “The immediate occasion for writing this book was Max Horkheimer’s fiftieth birthday, February 14th, 1945. The composition took place in a phase when, bowing to outward circumstances, we had to interrupt our work together. This book wishes to demonstrate gratitude and loyalty by refusing to acknowledge the interruption. It bears witness to a dialogue interiéur: there is not motif in it that does not belong as much to Horkheimer as to him who found the time to formulate it. The specific approach of Minima Moralia, the attempt to present aspects of our shared philosophy from the standpoint of subjective experience, necessitates that the parts do not altogether satisfy the demands of the philosophy of which they are nevertheless a part. The disconnected and non-binding character of the form, the renunciation of explicit theoretical cohesion, are meant as one expression of this. At the same time this ascesis should atone in some part for the injustice whereby one alone continued to perform the task that can only be accomplished by both, and that we do not forsake.” In: Minima Moralia: Reflections on a Damaged Life, translated by E.F.N. Jephcott. (Verso 2005 [NLR 1974]), 18.

Horkheimer to Adorno, 4/13/1945. In: Theodor W. Adorno, Max Horkheimer. Briefwechsel 1927-1969: Band III: 1945-1949. Edited by Christoph Gödde and Henri Lonitz (Suhrkamp Verlag, 2005), 50. Author’s translation.

For more on the conceptual developments behind the changes made to the title of the first chapter and the title of the book itself, see: James Schmidt, “Language, Mythology, and Enlightenment: Historical Notes on Horkheimer and Adorno's Dialectic of Enlightenment.” Social Research 65:4 (1998) 807-838. [link]

Schmidt: “As late as December 1946, Horkheimer still referred to the forthcoming book as Philosophische Fragmente (Horkheimer, 1996, p. 359). The earliest use of the new title in Horkheimer's published letters occurs in an August 29, 1947 letter to Paul Tillich, which states that the book will appear “before Christmas” (17, p. 884).” In: Ibid., 836. [Footnote No. 6.]

Adorno to Horkheimer, 2/25/1935. In: MHGS, Bd. 15 (1995), 328 [?]. Author’s translation.

Adorno to Horkheimer, 5/26/1936. In: MHGS, Bd. 15 (1995), [].

Max Horkheimer, “The End of Reason.” In: ZfS, Vol. 9, No. 3 (1941). Published in German the following year: Max Horkheimer, “Vernunft und Selbsterhaltung.” In: Walter Benjamin. Zum Gedächtnis. (1942), 17-59.

Horkheimer to Paul Tillich, 8/12/1942. In: A Life in Letters. Selected Correspondence by Max Horkheimer. Edited and translated by Evelyn M. Jacobson and Manfred R. Jacobson (University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 208-214. Translation modified.

Rolf Wiggershaus, The Frankfurt School: Its History, Theories, and Political Significance. Translated by Michael Robertson (Polity Press, 1994), 407.

Excerpt from: Horkheimer to Marcuse, 12/29/1948:

I believe I have already written you about how much I enjoyed your work on Sartre. Have you begun writing something else? Recently, I myself have been preparing a fundamental critique of psychology, for which, I believe, it is finally time. What are your thoughts on Lukacs’s Jungen Hegel [(1948)]? As far as I can see at this point, the theoretical yield is hardly worth the tremendous effort. It is indeed nice to see the idealistic legend of the young Hegel so energetically opposed, but, for all the materialistic content, the mode in which the topic is treated comes disconcertingly close to the intellectual attitude criticized in [Nietzsche’s] “The Uses and Disadvantages of History for Life.” Formulations such as the one about “Hegel’s vacillations and lack of clarity in the determination of decisive economic categories, particularly that of value,” have the spirit of the schoolmaster about them.

In: MHGS, Bd. 17 (1996), 1051. Author’s translation.

Quoted in: Dialectic of Enlightenment. Edited by Gunzelin Schmid Noerr, Translated by Edmund Jephcott. (SUP, 2002 [1987]), 241.

The quote is a translation from: “Rettung der Aufklärung. Diskussion über eine geplante Schrift zur Dialektik” (1946), in: MHGS, Bd. 12 (Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, 1985), 597-599·

Horkheimer to Pollock, 12/18/1945: “There is nothing new to report from here. I am working and hope to finish my program during the next week. I have concentrated almost exclusively on the first chapter, because it gives what one calls here the frame of reference. It would be a great joy if I could reorganize the following chapters—this would take 6 or 8 weeks—but I think I cannot afford it for three reasons. (1) It is not the English exoteric version of thoughts already formulated which matters [viz., Eclipse], but the development of a positive dialectical doctrine which has not yet been written. (2) I do not want to delay the day of delivery as agreed upon in the contract; not only because I hate such breaches of promise, but also because I think the book should be published as soon as possible, and that if there is a delay it should not be caused by us. (3) I definitely need a rest and if I go on working like I do now, the rest might have to be extended much longer and still not bring the same results as if it starts in January. Anyhow I think these last weeks, during which I made myself an expert in American pragmatism, will not be lost.” In: MHGS, Bd. 17 (1996), 687-688.

Horkheimer to Pollock, 3/27/1946. In: MHGS, Bd. 17 (1996), 714-715. Author’s translation.

The ‘external things’ (die äußeren Dinge) concern growing tensions between the ISR and Samuel Flowerman of the AJC over the fate of the research of the Scientific Department. Horkheimer goes on to say: “This includes, above all, the committee. I am deliberately giving Flowerman the opportunity to prepare a new attempt at sabotage. It would be all too easy to parry him beforehand, but any counteraction would place a new moral obligation on me and I must get away this time, even if we should lose out on serious amounts of money.” In: Ibid.

Adolph Lowe to Horkheimer, 8/12/1947: “If we could speak, the last chapter would naturally be in the foreground. I have never seen the “dialectic of the dialectic” described so impressively, and the positive underground of the often-maligned negativism, accordingly, shines forth from this with great clarity. I would just ask how a connection to the abandoned reconfiguration of the world, as you emphasize so strongly in the last pages, might be reestablished. Do we not have to have a “vision” of the new for this, and, if so, from which sources is this supposed to arise? You do not speak of the eschaton like the prophets, but rather you speak of what is at very least possible as itself an actuality. Of the countless details that have made me happy, the one that has remained most vividly in my memory is the remark that the “eternal ideals” are all negations of real sufferings and injustices. In this sense, everything good becomes utopia.” In: MHGS, Bd. 17 (1996), 872. Author’s translation.

See [MHGS Ed. Fn.:] “In his reply letter of 30 August 1947, MH addressed the "positive underground" highlighted by Lowe, reporting on his work on the planned continuation of the Dialectic of Enlightenment: “Every other free minute I spend working on the second part of the ‘Fragmente’ either with Teddie or preparing for the next day’s work. As you know, this part of our studies will be devoted to a positive theory of dialectics. We have started with the most difficult part of it, the Concept of Truth.” (MHA: 1 17.49) — However, these works seem to have hardly progressed beyond discussions (cf. the protocols of the conversation “Rettung der Aufklärung, Gespräche über eine angebrachte Schrift zur Dialektik” [1946], in: HGS 12, p. 593 ff.). In any case, there are no developed texts or text fragments dedicated to this project in the estates of either MH or Adorno.” In: Ibid., 873. Author’s translation.

Horkheimer to Paul Tillich, 8/29/1947. In: MHGS, Bd. 17 (1996), 884.

Paul Tillich to Horkheimer, early September 1947. In: MHGS, Bd. 17 (1996), 892-893. Author’s translation.

Adorno to his Parents, 1/12/1947: “Thomas Mann, whom I visited today, has written the new chapter of his novel, (Ed. Fn. 1. The chapter dealing with Adrian Leverkühn’s composition Doktor Fausti Weheklag.) following my suggestions to the letter. It is a very peculiar relationship. Tomorrow is a solemn day: Max and I are starting a big piece of work together. (Ed. Fn. 2. The close theoretical collaboration between Horkheimer and Adorno, as in the case of the Dialectic of Enlightenment, was not continued. At the time, both were still considering writing the book on dialectical logic.) I myself have completed another big text (Ed. Fn. 3. Adorno was working on the third part of Minima Moralia at the time.) I had been working on feverishly in bed. I am in the most productive condition possible, and extremely happy despite my laughable stomach business. It is probably a result of psychological factors, by the way, like all ulcers.” In: Letters to His Parents, 1939-1951 (2006), 274-275.

Gretel and Theodor Adorno to Adorno’s Parents, 1/20/1949: “On four afternoons every week, Teddie works with Max on the follow-up to their big text, in the mornings on the Heine, which is to be published in the Pacific Spectator, and then there are still countless technical matters that also need to be taken care of.” In: Ibid., 350.

Theodor and Gretel Adorno to Horkheimer, 9/23/1947: “I read a lot of [the] Phenomenology, it is the greatest book of its kind. And I have been thinking over the concept of the materialistic dialectic quite a bit. If only we could finally get to it in peace. …” In: Adorno, Horkheimer. Briefwechsel, Bd. III. (2005), 186. Author’s translation.