Hello all!

For this week, a few notes on Marx’s 1844 Manuscripts (or Paris Notebooks), specifically on the fourth section of the first manuscript—one given the heading “Alienated Labor” by the editors of the initial publication of the text in 1932.1 My plan is to produce a series of notes on a weekly basis, if possible, on the early works of Marx and Engels—including, but not limited to, Engels’ “Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy” (1843), The Holy Family (1845), and The German Ideology (1845-6). I’m starting with the 1844 Manuscripts only because my most recent research has been about the adaptation of the manuscripts by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari in Anti-Oedipus (1972). You can read my first essay, on Deleuze and Guattari’s use of the young Marx’s concept of industry to theorize desire, here, and my second essay, on their use of the young Marx’s thesis on atheism to overcome modern pieties, here.

A philosophical reading

First, however, I want to say something about what it might mean to read Marx philosophically—which, for better or worse, is what I’m setting out to do. As Louis Althusser once said, “there is not such thing as an innocent reading,”2 especially not of Marx and especially not in a philosophical reading of Marx! For Althusser, a philosophical reading of Marx concerns the relation between Marx’s Capital as a theoretical discourse to its object towards the articulation, and defense, of Marxism as a new scientific discourse (historical materialism).3 My purpose is, however, purely exegetical, and I take two models for exegetical reading and writing: Deleuze and Hegel. For Deleuze, in his preface to Difference & Repetition, a philosophical reading succeeds with the production of “a commentary [that] should act as a veritable double and bear the maximal modification appropriate to a double.”4 It is only, he continues, under the strictest repetition of the original text that a maximum of difference can be produced between the original text and the commentary (as in the case of Pierre Menard’s Quixote). This model subjects the text in question to a test, a test of the power of the text to produce strange, new effects (affective, perceptive, and conceptual in his final shorthand) for the reader. For Hegel, in his discussion of Spinoza’s system in the Science of Logic, a philosophical reading of a text succeeds with the elevation of the standpoint within that text on the strength of its own resources to the level at which its ultimate limitations are revealed and the reader passes on to a higher standpoint—the second necessarily informed by the limitations of first.5 Both models demand exacting fidelity to the text being read in each case for the sake of what we might say is the project of going beyond the text by means of the text. This kind of generosity—which, for Hegel, is the precondition for any critique worthy of the name—is, at its limit, what Adorno called “the attempt to contemplate all things as they would present themselves from the standpoint of redemption.”6 If these models of reading are pre-Marxist, I would contend, following Jameson’s argument in the final chapter of Marxism and Form, that they are at least not incompatible and at best complementary; that “philosophical thinking, if pursued far enough, turns into historical thinking, and the understanding of abstract thought ultimately resolves itself back into an awareness of the content of that thought, which is to say, of the basic historical situation in which it took place.” (346) This is his argument for the complementarity of the Hegelian and Marxist dialectics, the former a process of determining the powers and limits of a text from within the text itself and the latter a process of determining the powers and limits of a thinker restored to their historical situation.7 Whether one succeeds in producing a commentary on either of these models for philosophical reading, or whether such a commentary is useful for the reader whatsoever, clearly cannot be determined in advance of the effort to burn the text to completion like fallaway rocket boosters. Good exegesis is as difficult as it is rare, and keeping to these models means I won’t be repeatedly referring back to the real library of secondary literature written about the 1844 Manuscripts since their publication in 1932.8 However, in the composition of a philosophical exegesis, another danger, Hegel reminds us, lies in the fact that the ideal of purity corrupts, or the writer who strives for perfect presentation of a pure subject matter compromises their project in the endless, futile effort to ward off any intrusion of irrelevance, imaginative flight, or accident during a lapse of intellectual discipline.9

In the future, I plan on posting here about different theories of reading at the intersection of Marxism and philosophy—from Althusser’s discussion of what it would mean to learn to read Marx like Marx read classical political economy to a fuller treatment of Jameson’s Marxism & Form and the hermeneutic model he offers there. Until then, thanks for bearing with me! This will be the last meta-reflection on my own writing I post to this substack. As Deleuze reassures and warns us,

We write only at the frontiers of our knowledge, at the border which separates our knowledge from ignorance and transforms the one into the other. Only in this manner are we resolved to write. To satisfy ignorance is to put off writing until tomorrow—or rather, to make it impossible.10

The Critique of Political Economy in the 1844 Manuscripts

In what sense is the 1844 Manuscripts a critique of political economy? Across the humanist-anti-humanist divide, commentators have agreed that the manuscripts are not only Marx’s first real encounter with political economy, but also his first attempt at a critique of political economy as a theoretical discipline. It’s not until the end of the first manuscript, however, in the section titled “Alienated Labor,” that Marx explains his methodological approach to writing the preceding three sections—“Wages of Labor,” “Profit of Capital,” and “Rent of Land”—in which he quotes primarily and liberally from Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations to demonstrate repeatedly, in a phrase, that “social misery is the goal of the economy” under the capitalist regime of private property. (74) The real fight in the first three sections seems to take place between Smith and Smith—e.g., Smith vs Smith on whether the immiseration of the working class is a necessary consequence of the increase of wealth in capitalist societies (71-75), Smith vs Smith on whether the interests of the landlord are always identical with the interests of society (109-113), etc.—as Marx makes explicit the implicit contradictions in Smith’s theories of labor-wages, capital-profit, land-rent. In short, Marx’s method in the first three sections appears to be immanent critique in the purest sense: through a close reading of a single text as a closed world unto itself, revealing the contradictions therein. We are led to this conclusion by passages like the following, from “Wages of Labor”:

I maintain, however, that labor itself, not only in present conditions but universally in so far as its purpose is merely the increase of wealth, is harmful and deleterious, and that this conclusion follows from the economist’s [read: Smith’s] own argument, though he is unaware of it. (76)

Of course, a critique of political economy by means of political economy is not yet a critique of the discourse of political economy as such. The goal of Marx’s criticism in the first three sections appears to be forcing political economy to recognize the real consequences of the capitalist regime of private property, for which political economy produces both explanations and justifications. This explains why, for Marx, Ricardo has the rare distinction of treating men as “nothing” and the product as “everything” in his writing (98), an indifference to human life Marx finds implicit in Smith, despite the latter’s argument that the capitalist regime of private property is a moralizing force and pretense to the morality of political economy as a scientific discourse. Marx: “But Ricardo lets political economy speak its own language; he is not to blame if this language is not that of morals.” (173) My contention is that, for Marx in the 1844 Manuscripts, there are two problems with the discourse of political economy insuperable within political economy itself—(1) its self-understanding as, simultaneously, a moral and scientific discourse of the moralizing effect of capitalist society and (2) its inability to really explain the system of private property. Furthermore, for Marx, these two problems resolve into one: political economy cannot be both a scientific and moral discourse of capitalist society unless it fails to explain the system of private property. Consequently, there can be no real distinction for the author of the 1844 Manuscripts between the scientific analysis of society and the critique of political economy.

Only in the first two pages of “Alienated Labor” do we find Marx connecting the inability of political economy to avow the human consequences of the system of private property and the inability of political economy to explain the system of private property. To explain the system of private property, as we’ll see, political economy would have to grasp it as a historically specific form of the production and organization of social wealth through an analysis of the capitalist labor process or process of production. As a critical concept, alienated labor explains the formation of the system of private property on the basis of real separations—for example, the worker from the means of production and subsistence, the worker from the activity of work, etc.—internal to the labor process itself. Marx explains the derivation and significance of the concept of alienated labor as follows:

We have, of course, derived the concept of alienated labor (alienated life) from political economy, from an analysis of the movement of private property. But the analysis of this concept shows that although private property appears to be the basis and cause of alienated labor, it is rather a consequence of the latter, just as the gods are fundamentally not the cause but the product of confusions of human reason. At a later stage, however, there is a reciprocal influence. (131)

The concept of alienated labor, both indicated and unavowed by political economy itself, furnishes the ground that makes a critique of political economy possible. Though I won’t be able to explicate the concept of alienated labor in all four of its dimensions in this essay, my plan for the rest of this post is to reconstruct Marx’s argument for why the concept is both necessary and sufficient as a ground for the critique of political economy.

What does Marx say he’s doing in the opening pages of “Alienated Labor”? He concedes that he began from the presuppositions of political economy—the categories of private property, the division of labor, competition, exchange-value, the separation between labor/capital/land as the three sources of wealth and wages/profit/rent as the three forms of wealth—to demonstrate, in the words of political economy itself, that the regime of private property, which political economists serve by legitimating in the realm of theory, has three necessary consequences: (1) the immiseration of the worker proportional to the worker’s productivity, (2) the necessary restoration of monopoly through competition in a capitalist system, (3) the disappearance of the distinction between capitalists and landlords, industrial and agricultural workers, as society divides into two classes—property owners and propertyless workers.11

However, there is a slight difference between what Marx says he has done and what he actually does in the first three sections. As we’ll see, in each section, Marx not only draws out the implications of political economy from its own words, but also forces a confrontation between political economy—with Adam Smith serving as the primary representative of the discipline—and the real consequences of the regime of private property that political economists serve. This confrontation is staged in the first two sections on the basis of the economic writings of several socialists and social scientists regarding the immiseration of the working classes, the commodification of labor, proletarianization, new forms of impersonal social domination under capitalism, and the dislocation between private production and real social need (a dislocation poorly mediated by the market). These figures include Wilhelm Schulz, Constantin Pecquer, Charles Loudon, and Eugène Buret. In the third section, Marx hews closer to smith, using Smith’s theory of rent to criticize the romantic nostalgia for feudal landed property and to criticize Smith’s own “absurd” conclusion “that since the landlord exploits everything which benefits society, the interest of the landlord is always identical with that of society.” (108) These economic writings from other socialists—like the soon-to-be-published Conditions of the Working Class in England (1845) by Engels himself—allow Marx to stage the confrontation between the “legendary,” or mythical, discourse of the political economists and a “contemporary economic fact”—that of the commodification of labor, the devaluation of the human world proportional to the increasing value of the world of things, and the progressive, degenerating immiseration of the working classes. (121) The 1844 Manuscripts is impossible to grasp without this confrontation, which furnishes Marx with the elements and impetus for developing the critical concept of alienated labor.

For Marx, political economy is culpable for the production of a “legendary primordial condition” that “asserts as fact or event what it should deduce,” as in the example of the relation between the division of labor and exchange, which, for the political economist, is treated as a pre-given historical fact. (121) Marx compares this approach to theological “explanation” which “explains the origin of evil by the fall of man”—a tautological formula, a pseudo-explanation, in which explanandum and explanans are indistinguishable by their content. (Ibid.) Marx details the steps in the theoretical production of political economy: it begins with the fact of private property, but does not explain it, thereby conceiving the material process of the formation and accumulation of private property through static abstractions in the form of economic laws. Naturally, Marx continues, political economy also fails to comprehend these laws!

Providing an example for his claim that “what should be explained is assumed” by political economy, Marx refers to the “explanation” given by political economists of the relation between wages and profits by reference to “the interests of capitalists.” (120) Already, before the introduction of Marx’s materialist psychology in the third manuscript,12 we see Marx object to the moralistic and psychologistic explanations of economic phenomena by bourgeois political economy. In the context of criticizing political economy for explaining the existence of competition by reference to the subjective motivations of capitalists, Marx writes: “The only motive forces which political economy recognizes are avarice and the war between the avaricious, competition.” (121) Just as the interests of capitalists can’t explain the relation between wages and profits, the motive force of avarice can’t explain the phenomena of competition between capitalists. If, in each of these cases, Marx says what should be explained is assumed, then class interests and subjective motivations, rather than explaining anything, need to be explained themselves by the process of class formation and, I contend, the production of subjects by the production process. Much of the third manuscript will be dedicated to an explanation of avarice and envy under the regime of private property, and the types of subject produced by the constant creation and frustration of new needs in capitalist society.13

Furthermore, because the political economists fail to treat private property in its formation by material processes—which Marx will attempt to do historically in “Rent of Land,” in his explanation for the rise of private out of feudal property, and logically in “Alienated Labor,” as he establishes the conditions of possibility for the formation of private property given the reality of human species-being—and conceive of it only according to general, static laws that govern the legitimation, distribution, acquisition, and accumulation of private property, they commit themselves to a spurious distinction between law and accident. As a result, they explain competition, in Marx’s example, as an accident of the generalized possession of private property, an accident explained itself by another accident—the motive forces of avarice and war between the avaricious. Marx: “Political economy tells us nothing about the extent to which these external and apparently accidental conditions are simply the expression of a necessary development.” (120) Here, Marx provides us with the criteria for evaluating the success of a truly historical explanation: to what extent have we been able to present the actual, present state of private property as the result of a necessary development? By this criteria, Marx continues, political economy fails, even to the point of treating exchange as an accidental fact relative to the laws of private property. (120-121)

Consequently, because their failure to understand the necessary, or real, interconnection between private property and competition, political economists were able to produce theoretical pseudo-explanations of the decline of the feudal organization of production by reference to “will and force,” as if the subjective motives and accidental powers of individual economic agents brought down feudal production by opposing its inherited monopolies with competition, the old guild system with the doctrine of freedom of the crafts, and the great estates with the division of landed property. (121) It is because of the abstract formalism of political economy, the static generality of its economic laws, that it was only able to conceive of “competition, freedom of crafts, and the division of landed property (...) as accidental consequences brought about by will and force, rather than as necessary, inevitable, and natural consequences of monopoly, the guild system, and feudal property.” (Ibid.) In every case—monopoly, the guild system, and feudal property—the historical development of each form of organization necessitates by the logic of its own essence its supersession by the form political economy claims opposed it accidentally from without.

Though Marx does not discuss the supersession of the guild system by freedom of the crafts in these manuscripts, he will, in the last few pages of “Rent of Land,” reconstruct the supersession of monopoly by competition and the supersession of feudal property in the form of large estates by the division of landed property as, respectively, a development in the essence of monopoly and a development of the ‘germ’ of capitalist private property contained in feudal landed property. In both cases, moreover, Marx says the supersession of monopoly by competition and feudal property by the division of land restores on an expanded scale monopoly on the one hand and large landed property on the other, now in the hands of capitalists instead of feudal lords. Marx explains that the egalitarian political impulse against feudal monopoly and large estates only managed to negate the existence of each in the feudal organization of production and not the essence of both: private property itself. The partial negation of private property in the era of liberal-bourgeois revolutions and reforms can retrospectively be grasped as a necessary stage in the actualization of the essence of private property, the fullest expression of which is the accumulation of capital.14

The task Marx sets for himself in the opening of “Alienated Labor” is thus

to grasp the real connection between this whole system of alienation—private property, acquisitiveness, the separation of labor, capital and land, exchange and competition, value and the devaluation of man, monopoly and competition—and the system of money. (121)

For Marx, only this connection can explain the form private property takes in capitalist society, a society in which money mediates all social life, and, having no master (“a new adage: l’argent n’a pas de maître”), as a system is “the complete domination of living men by dead matter.” (115) Therefore, against the “legendary primordial condition” with which political economy begins its explanations, a “condition [that] does not explain anything [but] removes the question into a grey and nebulous distance,” Marx insists on beginning “from a contemporary economic fact”: “The devaluation of the human world [which] increases in direct relation to the increase in value of the world of things.” (121) The domination of living men by dead matter, in other words, begins in the real process of production under capitalism. In the capitalist labor process, “Labor does not only create goods; it also produces itself and the worker as a commodity, and indeed in the same proportion as it produces goods.” (Ibid.) The concept of alienated labor enables us to grasp private property in the process of its development, from the supersession of feudal private property to the marriage of private property to the money system. The concept of alienated labor enables us to grasp the world in which dead matter dominates the living in its very formation, re-formation, and expansion. For Marx, this concept makes possible a critique of the political economists who treat the capitalist regime of private property as if it sprang into existence fully armed from their own minds as Athena was said to from the head of Zeus.

Conclusion

In the 1844 Manuscripts, Marx takes up the critique of political economy in earnest through the critical concept of alienated labor. This concept enables us to grasp the capitalist system of private property (or the marriage of the system of private property to the system of money) in the process of its formation, which is only the labor process itself. “Alienation” designates, as we’ll see, four real separations (of laborer from their product, laborer from their work, laborer from their human species-being, laborer from other people) in the labor process itself, separations which both account for the emergence of the capitalist system of private property and are reciprocally reinforced by that same system at a later stage. For the author of the 1844 Manuscripts, the concept of alienated labor is simultaneously a scientific and critical concept—or, more to the point, to apprehend the capitalist system of private property in its formation is necessarily a critical exposition of the intolerability of life in capitalist society. For Marx, political economy had to fail as a scientific discipline to grasp the material process of the formation of the capitalist system of private property in order to succeed as a moral discourse lionizing the moral effects, for example, of free trade by private enterprise as the transformation of private vice into public virtue—as in the case of Mandeville’s Fable of the Bees.15 It was necessary, therefore, that political economy regarded private property as a brute fact, or a historical given, rather than as a historically specific form of producing, distributing, and consuming wealth. It was solely on this condition that political economy was capable of making the spurious distinction between the laws that govern private property and various accidents—for ex., the triumph of competition over feudal monopoly, the subjective motivations (greed or avarice) of individual economic agents that drove the decline of feudal production. (This last example is especially relevant to Marx’s lifelong concern with the fantasies of capitalist anthropology, whether we take Smith’s “natural propensity to truck, barter and exchange” or bourgeois social contract theory’s imaginary individual in the state of nature, as Marx criticizes in the opening of the Grundrisse, as targets.) Concisely, Marx argues political economy fails to present the capitalist system of private property as a necessary historical development. Crucially, for Marx, political economy is incapable of this scientific presentation of the capitalist system of private property because it would require the political economist to grasp the necessary connection between that system (itself the union of private property and the mediation of all social life by money) and the unlivable lives of the immiserated. When we return, therefore, to the opening sections of the 1844 Manuscripts, where Marx appears to take the terms of political economy for granted, we can find the concept of alienated labor already at work in Marx’s procedure of explicating the implicit, but unavowed, consequence that necessarily follows from the political economist’s conceptualization of private property: social misery is the goal of the economy. For Marx to avow the unavowed consequences of the capitalist system of private property implied in the writings of the political economists indicates, therefore, that Marx, as a critic of political economy’s pretension to science, has already installed himself at the core of the labor process where the formation of that system is lived by the immiserated worker.

From the beginning, then, Marx takes the critique of political economy further than a criticism of the hypocrisy of the political economist who celebrates the moralizing effects of the capitalist system of private property. For Marx, this hypocrisy is the necessary condition for the existence of political economy in the first place, and, with the advent of a figure like Ricardo, who abandons the pretense to moral discourse in political economy under compulsion to theorize the necessity of class antagonism, “the bourgeois science of economics had reached the limits beyond which it could not pass.”16 What this suggests is that Marx’s critique of Smith is less naïve and trusting of Smith than it appears.

For Marx to explicate the implicit, but unavowed, consequences of Smith’s theory of private property—in a phrase, that social misery is the goal of the economy—Marx already had to adopt a critical point of departure outside of the theoretical ambit of political economy. In “Wages of Labor,” Marx not only begins to develop the contradictions between Smith’s theory of private property and Smith’s false, utopian conclusions about the moralizing effects of the capitalist system of private property, but also offers us a stark contrast between these utopian conclusions and the real, existential consequences of the system Smith glorifies. (Hence the importance for Marx of the socialist economists and sociological researchers like Schulz, Pecquer, Loudon, and Buret, who study immiseration, proletarianization, the commodification of labor, and the impacts of these economic tendencies on the proletariat from the perspective of public health.) These consequences necessarily lie outside of the domain of political economy: “Political economy does not deal with [the worker] in his free time, as a human being, but leaves this aspect to the criminal law, doctors, religion, statistical tables, politics, and the workhouse beadle.” (76) Rather than taking political economy at its word as a reflection in theory that mirrors the economic reality of the capitalist system of private property,17 Marx’s task in the opening triad of the 1844 Manuscripts—“Wages of Labor,” “Profit of Capital,” and “Rent of Land”—is twofold. On the one hand, Marx demonstrates that the utopian conclusions of political economy do not follow from its analysis of private property. On the other, Marx indicates the limitations of political economy regarding its analysis of the internal logic of private property and its necessary ignorance of the existential consequences of that logic for the mass of capitalist society. These two indications—of the limits of political economy’s analysis of private property and of the constitutive neglect in political economy of the fate of the worker—are the concern of “Alienated Labor.”

As I argued above, the concept of alienated labor is a critical concept that enables us to simultaneously apprehend the capitalist system of private property in its formation and expose the necessary immiseration of the worker under that system. For Marx, political economy is not capable of apprehending either, given its pretension to being both a scientific discipline analyzing private property and a moral discourse lionizing the moralizing effects of private property. To put it in the form of a chiasmus, Marx’s preferred rhetorical device in the 1844 Manuscripts: only the concept of alienated labor enables us to apprehend capitalist property relations through immiseration and immiseration through capitalist property relations.

(For Marx in the 1844 Manuscripts, the capitalist system of private property is the conjunction of private property, which existed before capitalism proper, and the money system, or the mediation of all social life by money. That this conjunction between private property and money, which itself culminates in the process of capital accumulation, is the inevitable development of the essence—in other words, constitutive relation—of private property is argued for explicitly in “Rent of Land.”)

Beyond the limit of political economy, Marx undertakes an analysis of the historical formation of the capitalist system of private property in the four separations (alienation of: worker from product, worker from work, worker from species-being, worker from other people of either pole of class society) that characterize the alienated labor process. In his own words: “Political economy conceals the alienation in the nature of labor in so far as it does not examine the direct relationship between the worker (work) and production.” (124) With this in mind, we can read the opening triad of the first manuscript keeping an eye out for two moments in Marx’s argument: first, the disconnect between the theory of private property we find in political economy and the utopian conclusions of the political economist; second, any indication of the limits in political economy either in its analysis of private property or insofar as it fails to recognize the immiseration of the worker as a necessary consequence of the capitalist system of private property. Before that, however, we need to develop the concept of alienated labor, without which the critique of political economy would never have begun.

Thanks for reading!

James Crane

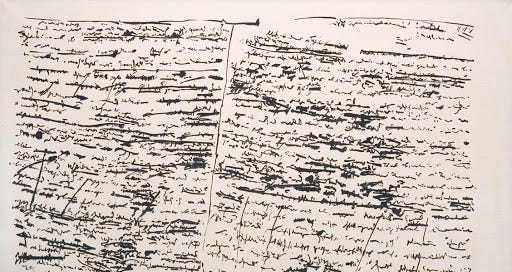

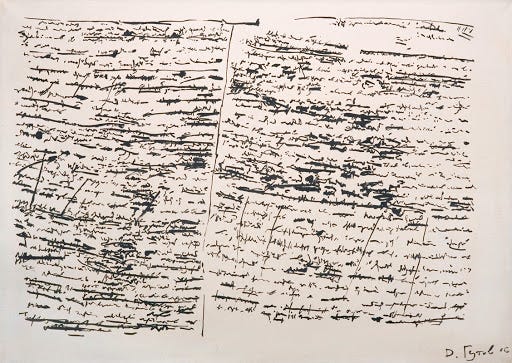

Karl Marx, Early Writings. Trans. and ed. by T.B. Bottomore, fwd. by Erich Fromm. (1964) In Bottomore’s introduction, he explains the organization of the first manuscript as follows: “The first manuscript comprises nine double sheets (thirty-six pages). Each page is divided by two vertical lines to form three columns, which are headed respectively, “Wages of Labor,” “Profits of Capital,” and “Rent of Land.” These constitute the first three sections of the published text. On page XII of the manuscript, however, Marx began to write on a different subject, ignoring the division of the pages into three columns; this portion of the manuscript was given the title “Alienated Labor” by the editors of the MEGA. [He is referring primarily to the work of D. Riazanov, who prepared and published the 1844 Manuscripts under the auspices of the Marx-Engels Institute in 1932.] The manuscript breaks off on page XXVII.” (p. xvii)

Althusser, “From Capital to Marx’s Philosophy” (1968).

Ibid.: “We were all philosophers. We did not read Capital as economists, as historians or as philologists. We did not pose Capital the question of its economic or historical content, nor of its mere internal ‘logic’. We read Capital as philosophers, and therefore posed it a different question. To go straight to the point, let us admit: we posed it the question of its relation to its object, hence both the question of the specificity of its object, and the question of the specificity of its relation to that object, i.e., the question of the nature of the type of discourse set to work to handle this object, the question of scientific discourse. And since there can never be a definition without a difference, we posed Capital the question of the specific difference both of its object and of its discourse – asking ourselves at each step in our reading, what distinguishes the object of Capital not only from the object of classical (and even modern) political economy, but also from the object of Marx’s Early Works, in particular from the object of the 1844 Manuscripts; and hence what distinguishes the discourse of Capital not only from the discourse of classical economics, but also from the philosophical (ideological) discourse of the Young Marx.”

See Deleuze’s preface to Difference & Repetition: “The history of philosophy is the reproduction of philosophy itself. In the history of philosophy, a commentary should act as a veritable double and bear the maximal modification appropriate to a double. (One imagines a philosophically bearded Hegel, a philosophically clean-shaven Marx, in the same way as a mustached Mona Lisa.) It should be possible to recount a real book of past philosophy as if it were an imaginary and feigned book. Borges, we know, excelled in recounting imaginary books. But he goes further when he considers a real book, such as Don Quixote, as though it were an imaginary book, itself reproduced by an imaginary author, Pierre Menard, who in turn he considers to be real. In this case, the most exact, the most strict repetition has as its correlate the maximum of difference (‘The text of Cervantes and that of Menard are verbally identical, but the second is almost infinitely richer…’). Commentaries in the history of philosophy should represent a kind of slow motion, a congelation or immobilization of the text: not only of the text to which they relate, but also of the text in which they are inserted—so much so that they have a double existence and a corresponding ideal: the pure repetition of the former text and the present text in one another.” (pp. xxi-xxii)

Hegel, The Science of Logic: “Further, any refutation would have to come not from outside, that is, not proceed from assumptions lying outside the system and irrelevant to it. The system need only refuse to recognize those assumptions; the defect is such only for one who starts from such needs and requirements as are based on them. (…) Effective refutation must infiltrate the opponent’s stronghold and meet him on his own ground; there is no point in attacking him outside his territory and claiming jurisdiction where he is not. The only possible refutation of Spinozism can only consist, therefore, in first acknowledging its standpoint as essential and necessary and then raising it to a higher standpoint on the strength of its own resources.” (p. 512)

Adorno, Minima Moralia: “Finale. - The only philosophy which can be responsibly practised in face of despair is the attempt to contemplate all things as they would present themselves from the standpoint of redemption. Knowledge has no light but that shed on the world by redemption: all else is reconstruction, mere technique. Perspectives must be fashioned that displace and estrange the world, reveal it to be, with its rifts and crevices, as indigent and distorted as it will appear one day in the messianic light. To gain such perspectives without velleity or violence, entirely from felt contact with its objects - this alone is the task of thought. It is the simplest of all things, because the situation calls imperatively for such knowledge, indeed because consummate negativity, once squarely faced, delineates the mirror-image of its opposite. But it is also the utterly impossible thing, because it presupposes a standpoint removed, even though by a hair's breadth, from the scope of existence, whereas we well know that any possible knowledge must not only be first wrested from what is, if it shall hold good, but is also marked, for this very reason, by the same distortion and indigence which it seeks to escape. The more passionately thought denies its conditionality for the sake of the unconditional, the more unconsciously, and so calamitously, it is delivered up to the world. Even its own impossibility it must at last comprehend for the sake of the possible. But beside the demand thus placed on thought, the question of the reality or unreality of redemption itself hardly matters.” (p. 247)

Jameson: “Thus dialectical thought is in its very structure self-consciousness and may be described as the attempt to think about a given object on one level, and at the same time to observe our own thought processes as we do so: or to use a more scientific figure, to reckon the position of the observer into the experiment itself. In this light, the difference between the Hegelian and the Marxist dialectics can be defined in terms of the type of self-consciousness involved. For Hegel this is a relatively logical one, and involves a sense of the interrelationship of such purely intellectual categories as subject and object, quality and quantity, limitation and infinity, and so forth; here the thinker comes to understand the way in which his own determinate thought processes, and indeed the very forms of the problems from which he sets forth, limit the results of his thinking. For the Marxist dialectic, on the other hand, the self-consciousness aimed at is the awareness of the thinker’s position in society and in history itself, and of the limits imposed on this awareness by his class position—in short of the ideological and situational nature of all thought and of the initial invention of the problems themselves. Thus, it is clear that these two forms of the dialectic in no way contradict each other, even though their precise relationship remains to be worked out.” (340)

As for the Theoretical Anti-humanist literature on the subject, see Althusser’s For Marx (1965)—especially the chapters “On the Young Marx,” “The ‘1844 Manuscripts’ of Karl Marx,” and “Marxism and Humanism.” For a more specific, though indirect, treatment of the critical method in Marx’s 1844 Manuscripts from the same camp—and a helpful contrast between this method and the ‘mature’ Marx’s critique of political economy in Capital—see Jacques Rancière’s “The Concept of Critique and the Critique of Political Economy: From the 1844 Manuscripts to Capital” in Reading Capital (1965). For Marxist Humanist literature on the subject, see Erich Fromm’s Marx’s Concept of Man (1961), Henri Lefebvre’s Dialectical Materialism (1940), Agnes Heller’s The Theory of Need in Marx (1974), and the work of Raya Dunayevskaya and Herbert Marcuse. (Additional self-avowed Marxist Humanist texts I can’t help recommending: CLR James’ “Dialectical Materialism and the Fate of Humanity” (1947) and Grace Lee and James Boggs’ Revolution and Evolution in the Twentieth Century (1974).) For a comprehensive reconstruction of Marx’s theory of alienation across his whole body of work, of which only three chapters are available on marxists.org, see István Mészáros’ Marx’s Theory of Alienation (1970). See also Lucio Colletti’s introduction to Karl Marx: Early Writings (1974).

Hegel, The Science of Logic: “But I must admit that such an abstract perfection of presentation must generally be renounced; the very fact that the logic must begin with the purely simple, and therefore the most general and empty, restricts it to expressions of this simple that are themselves absolutely simple, without the further addition of a single word; only allowed, as the matter at hand requires, would be the negative reflections intended to ward off and keep at bay whatever the imagination or an undisciplined thinking might otherwise adventitiously bring in. However, such intrusive elements in the otherwise simple immanent course of the development are essentially accidental, and the effort to ward them off would, therefore, be itself tainted with this accidentality; and besides, it would be futile to try to deal with them all, precisely because they lie outside the essence of the subject matter, and incompleteness is at best what would have to do to satisfy systematic expectations.” (p. 20)

Deleuze, Difference & Repetition. p. xxi

Marx: “We have begun from the presuppositions of political economy. We have accepted its terminology and its laws. We presupposed private property; the separation of labor, capital, and land, as also of wages, profit, and rent; the division of labor; competition; the concept of exchange value, etc. From political economy itself, in its own words, we have shown that the worker sinks to the level of a commodity, and to a most miserable commodity, that the misery of the worker increases with the power and volume of his production; that the necessary result of competition is the accumulation of capital in a few hands, and thus a restoration of monopoly in a more terrible form; and finally that the distinction between capitalist and landlord, and between agricultural laborer and industrial worker, must disappear, and the whole of society divide into the two classes of property owners and propertyless workers.” (p. 120)

A concept I’ll defend in a later post. Marx, in “Private Property and Communism”: “It can be seen that the history of industry and industry as it objectively exists is an open book of the human faculties, and a human psychology which can be sensuously apprehended. This history has not so far been conceived in relation to human nature, but only from a superficial utilitarian point of view, since in the condition of alienation it was only possible to conceive real human faculties and human species-action in the form of general human existence, as religion, or as history in its abstract, general aspect as politics, art, and literature, etc. Everyday material industry (which can be conceived as part of that general development; or equally, the general development can be conceived as a specific part of industry since all human activity up to the present has been labor, i.e. industry, self-alienated activity) shows us, in the form of sensuous useful objects, in an alienated form, the essential human faculties transformed into objects. No psychology for which this book, i.e. the most tangible and accessible part of history, remains closed, can become a real science with a genuine content. What is to be thought of a science which stays aloof from this enormous field of human labor, and which does not feel its own inadequacy even though this great wealth of human activity means nothing to it except perhaps what can be expressed in the single phrase—“need,” “common need”?” (pp. 162-163)

See the opening paragraphs of “Needs, Production, and Division of Labor” in the third manuscript. (pp. 168-169)

See the last few pages of “Rent of Land” in the first manuscript: “The division of landed property negates the large-scale monopoly of landed property, i.e. abolishes it, but only by generalizing it. It does not abolish the basis of monopoly, private property. It attacks the existence, but not the real essence, of monopoly, and in consequence it falls victim to the laws of private property. For the division of landed property corresponds to the movement of competition in the industrial sphere.” (p. 116)

And: “Just as large landed property can return the reproach of monopoly made from the standpoint of small landholdings, since the division of land is also based on the monopoly of private property, so can the small holdings reject the reproach of having divided the land, for the division of land exists also in the case of large estates, but in an inflexible, crystallized form. Private property, indeed, is everywhere based upon division. Moreover, since the division of landed property leads again to large landed property as capital wealth, feudal property is bound to be divided, or at least to fall into the hands of capitalists, however it may twist and turn.” (p. 117)

Mandeville, a direct influence and spiritual ancestor to Adam Smith, in The Fable of the Bees (1714):

So Vice is beneficial found,

When it’s by Justice lopt and bound;

Nay, where the People would be great,

As necessary to the State,

As Hunger is to make ’em eat.

Bare Virtue can’t make Nations live

In Splendor; they, that would revive

A Golden Age, must be as free,

For Acorns, as for Honesty.

Capital, “Postface to the Second Edition”: “Insofar as political economy is bourgeois, i.e. insofar as it views the capitalist order as the absolute and ultimate form of social production, instead of as a historically transient stage of development, it can only remain a science while the class struggle remains latent or manifests itself only in isolated and sporadic phenomena. (…) In France and England the bourgeoisie had conquered political power. From that time on, the class struggle took on more and more explicit and threatening forms, both in practice and in theory. It sounded the knell of scientific bourgeois economics. It was thenceforth no longer a question whether this or that theorem was true, but whether it was useful to capital or harmful, expedient or inexpedient, in accordance with police regulations or contrary to them. In place of disinterested inquirers there stepped hired prize-fighters; in place of genuine scientific research, the bad conscience and evil intent of apologetics.” (pp. 96-97)

The argument that political economy is, for the author of the 1844 Manuscripts, “the mirror in which economic facts are reflected” is made by Jacques Rancière in “The Concept of Critique and the Critique of Political Economy: From the 1844 Manuscripts to Capital” in Reading Capital (1965). Rancière makes this argument on the basis of a single quote from the 1844 Manuscripts, taken from the section titled “Preface” originally located in the third manuscript, in which Marx calls his research into political economy “empirical analysis,” from which Rancière infers that Marx takes researching political economy as a 1:1 stand-in for empirical research into economic reality. (p. 83) Rancière’s other two grounds for this claim are taken from Marx’sCritique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right(1843)—in which Marx claims that the state reflects, as a mirror, the contradictions of civil society—and a letter to Ruge from September 1843—in which Marx claims something similar about the status of the state and religion as “special places where the contradictions [of civil society] come to be reflected.” (Ibid.) Like Louis Althusser inFor Marx(1965)—specifically in “Marxism and Humanism,” “On the Young Marx,” and “The ‘1844 Manuscripts’ of Karl Marx”—Rancière reads the 1844 Manuscripts indirectly, through Feuerbach as a proxy (especially Feuerbach’s theory of essence and object) or Marx’s own writings from the previous year (“Letter to Ruge,” Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right), rather than reading the 1844 Manuscripts directly.

(It is because of this indirect approach to reading the 1844 Manuscripts that Rancière’s criticism of Marx’s deployment of “the classical image of alienation” in the 1844 Manuscripts remains incomplete, much like Althusser’s criticism of the “empiricist-idealist” approach supposedly found in the 1844 Manuscripts. Both Rancière and Althusser import an entirely Feuerbachian model of alienation into the 1844 Manuscripts according to which “essence” or “species-being” is understood as a transhistorical generality waiting to be realized in a revolutionary event. I have already argued, through the work of Gérard Granel, that this reading of species-being is mistaken given the continuity between the 1844 Manuscripts, the “Theses on Feuerbach” (1845), and The German Ideology (1846) in Marx’s use of the concept of industry, according to which species-being is conceived of as coextensive with the real process of social production and reproduction. In a future post on the 1844 Manuscripts, I will make the claim, somewhat in agreement with Lucio Colletti’s in his introduction to Marx’s Early Writings (1974), that in the 1844 Manuscripts Marx conceives of species-being, or human essence, as “no more than the functional relationships mediating man’s working rapport with nature and with himself” (p. 54). If this is the case, Rancière’s distinction between alienation from essence in the 1844 Manuscripts and the reification of social relations in Capital needs to be re-examined.)

Rancière admits that he reads the 1844 Manuscripts indirectly: “We shall not deal with the whole theoretical structure of the Manuscripts. We prefer to approach the text indirectly by asking ourselves the question: What is the place of political economy in the Manuscripts?” (p. 81) It is perhaps a consequence of Rancière’s refusal to ‘deal with the whole theoretical structure of the Manuscripts’ that explains the following claim: “There is one remarkable fact in the Manuscripts. The problem of political economy as a discourse with claims to be scientific is not really posed.” (p. 82) This is untenable. He does, however, follow up with a much stronger observation: “It is true that in the Second Manuscript Marx talks of the progress of political economy, but this is only a progress in cynicism: economists admit more and more frankly the inhumanity of political economy.” (Ibid.) Rancière’s mistake is assuming the contradiction between a critique of political economy as a scientific discourse and a recognition the progress political economy made as a scientific discourse.

To the best of my knowledge, Rancière is referring to the following passage from the second manuscript, the section titled “The Relationship of Private Property”: “It is a great step forward by Ricardo, Mill, et al., as against Smith and Say, to declare the existence of human beings—the greater or lesser human productivity of the commodity—as indifferent or indeed harmful. The true end of production is not the number of workers a given capital maintains, but the amount of interest it earns, the total annual saving.” (p. 138) As I noted in my last post, this is a praise Marx makes of Ricardo elsewhere in the manuscripts: 1) in the first manuscript, the section “Profit of Capital,” where Marx quotes Say’s criticism that “For Ricardo men are nothing, the product is everything” (p. 98); 2) in the third manuscript, the section “Private Property and Labor,” where Marx identifies Ricardo with an increasing cynicism in political economy (in contrast to earlier political economists such as Smith) as a consequence in theory from the further development of industry in practice (pp. 148-149); 3) in the third manuscript, the section “Needs, Production, and Division of Labor,” where Marx defends Ricardo’s cynicism from M. Michel Chevalier on the grounds that “Ricardo lets political economy speak its own language; he is not to blame if this language is not that of morals.” (p. 173) On the one hand, Rancière is clearly correct that Marx identifies the increasing cynicism of a Ricardo contrasted with an Adam Smith as progress in political economy.

On the other, Rancière ignores the passage in “Needs, Production, and Division of Labor” where Marx criticizes Ricardo’s condemnation of luxury on the grounds that Ricardo is still bound to political economy as a moral discourse. (p. 172) Most damning for Rancière’s argument, however, is the persistence of Marx’s argument that Ricardo’s contributions to the political economy were not only scientific, but that the scientific character of Ricardo’s contributions—crucially, adopting the antagonism of class interests as a point of departure, “naïvely taking this antagonism for a social law of nature”—were a symptom not only of the historical development of class struggle contrasted with the earlier historical situation of political economy, but also indicated the ultimate limitations of political economy as a scientific discourse had been achieved and beyond which no more progress could be made. (cf. “Postface to the Second Edition” (1873), Capital, pp. 96-97)

To conclude: there is no contradiction for Marx, either in the 1844 Manuscripts or Capital, between the recognition of the progress Ricardo made relative to earlier political economists in reacting to the historical development of industry (as Marx says in 1844) or class struggle (as Marx says in 1873) and criticism of political economy as a scientific discourse. It is, rather, precisely due to the scientific character of Ricardo’s contributions—naïvely transhistorical as they may have been, given the necessarily transhistorical frame of political economy—that Marx can announce a time of death for political economy as a scientific discourse. As for Rancière’s claim that ‘the problem of political economy as a discourse with claims to be scientific is not really posed,’ debunking it is really as straightforward as reading the opening pages of “Alienated Labor.” Whether or not Marx succeeds in producing a critique of political economy in the 1844 Manuscripts is a separate issue. For now it is enough to note that Marx does pose the problem of the scientific status of political economy in this text to the extent that he articulates through the critical concept of alienated labor both the absolute limits of its analysis of private property and its constitutive neglect of the labor process.