M.N. Roy's "The Spiritualist West" as Critical Theory (1936)

Ellen Gottschalk's Letter to Horkheimer on Roy's Prison Writings

Introductory Note: M.N. Roy’s “Traditional and Critical Theory.”

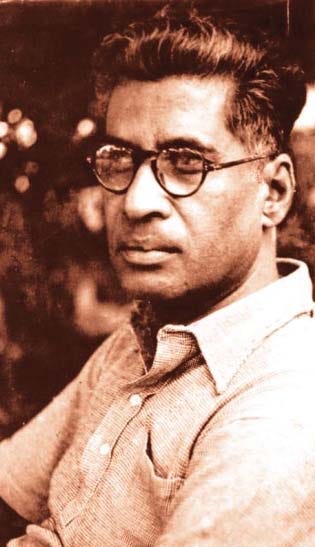

In August 1936, Hans Klaus Brill, then general secretary of the ISR’s branch at the École Normale Supérieure (now remembered primarily for making the cuts that instigated the controversy over Walter Benjamin’s “Work of Art” essay)1 forwarded a letter to New York for Max Horkheimer from an old acquaintance in the radical left-wing academic and activist circles of late 1920s Germany—Ellen Gottschalk (1904-1956), collaborator and partner of M.N. Roy (1887-1954), co-founder of the communist parties of Mexico and India and socialist-humanist philosopher.2 In the letter, Gottschalk (after 1937, Gottschalk-Roy) makes three requests of Horkheimer: (1) that Horkheimer look through the enclosed materials for Roy’s planned “major work,” a book under the provisional title of The Spiritualist West, which included an outline of the book and 24 fragments sourced from Roy’s prison letters to Gottschalk; (2) that Horkheimer consider making arrangements with Pollock to offer Gottschalk and Roy an official contract with the ISR (apparently Gottschalk, through the intermediary of Eduard Fuchs, discussed this possibility with Pollock several years prior) or perhaps even help Gottschalk and Roy secure funding for the creation of an Indian branch of the Institute for Social Research; (3) that, if Horkheimer is unable to fulfill either of the previous two requests, the ISR at least send Gottschalk another letter with a “Quasi-contract,” as Pollock apparently had in 1931, to help her renew her passport and facilitate her travel to rejoin Roy in India in anticipation of his early release.

While I have not been able to find any further documentation of Horkheimer’s correspondence with Ellen Gottschalk and M.N. Roy—Horkheimer may have delegated the response to Pollock or Hans Klaus Brill—it was common practice for the ISR throughout the 1930s and 1940s to write ‘quasi-official’ documents for fellow exiles who would never really be employed for the ISR. Even after the effective dissolution of the ISR for financial reasons in 1941, it still supported more than 200 refugees through WWII—if not with research funding, at least with references under a very official-looking letterhead for a virtually non-existent institution compared to its international operations in the mid-1930s.3 More important, however, is the substance of the request: Gottschalk did, in fact, have good reason to expect the Institute’s interest in Roy’s work.

Context of the Letter: Roy’s Imprisonment (1931-1936).

After returning to India in late 1930, Roy was arrested in June 1931 on a warrant issued almost ten years prior for treason and conspiracy with the Communist International to incite violence against the sovereign rule of the British crown in India. In early 1932, Roy was sentenced to 12 years in prison, and though he was not allowed to deliver a speech in his own defense at his trial, a copy was smuggled out and printed in 1932, including an abridged English translation under the title: “I Accuse”: From the Suppressed Statement of Manabendra Nath Roy on Trial for Treason Before Sessions Court, Cawnpore, India.4

The crux of the prosecution case is that force and violence are advocated in the documents which are alleged to be written by me. But force is force. The moral philosophy of the ruling power is that force becomes criminal when directed against it but that it is an instrument of virtue when employed for the preservation of the ruling power. In other words the mercenary army with which the sovereignty of the British is maintained in a foreign country is an instrument of moral, or virtuous, force. The rifles employed in putting down the pauperized peasants of Malabar or Burma are the arms of God. But the same weapons in the hands of the oppressed people of India fighting for freedom are instruments of crime. Airplanes bombing the Frontier tribesmen are vehicles of virtue, teaching those depraved people a moral lesson, but any resistance on the part of the latter is “criminal.” The oppressed people and exploited classes are not obliged to respect the moral philosophy of the ruling power. The sovereign right of the Indian people is usurped by foreign power and as the foreign usurpers maintain themselves in power by force, the Indian people are obliged to use force to recover their sovereign right. A despotic power is always overthrown by force. The force employed in this process is not criminal. On the contrary, precisely the guns carried by the army of the British government of India are instruments of crime. They become instruments of virtue when they are turned against the imperialist state. Weapons in the hands of the oppressed masses of India will be so many hammers to break the chain of a colonial slavery binding one-fifth of the human race.5

In the defense, Roy “exclusively” uses “liberal English thinkers and respectable constitutional lawyers” to defend himself6—particularly his open activities with the Communist International for the sake of overthrowing British colonial rule (Roy had in fact been expelled from the Comintern in 1929 during Stalin’s purges of the left-opposition) and his open recognition of the necessity of armed resistance that is not invented by the communists but imposed by the nature of imperialism itself.7 Roy would serve 5 years and 4 months of his sentence, reduced to 6 years in 1933 (for lack of evidence of conspiracy), across four different prisons. Under grueling conditions and neglect, Roy suffered from chronic, recurring illness (see: [Fragment 15: 21.7.35.]), the effects of which he would never fully recover from. He was released in November 1936 because of his poor and worsening health. During this time, Ellen Gottschalk worked closely with Roy from France, having escaped Nazi Germany to Paris, and organized a letter-writing campaign on his behalf with notable socialist intellectuals while she coordinated Roy’s research and edited the letters and manuscripts he managed to send her.

Content of the Letter: The Spiritualist West as Critical Theory.

In a recent essay, Christian Fuchs (2019) has argued that the parallels between M.N. Roy’s work and that of the ‘first generation’ of the Frankfurt School (Adorno, Horkheimer, Marcuse) are significant enough that Roy’s work could be said to develop a ‘dialectic of enlightenment’ of its own.8 In her letter to Horkheimer, Gottschalk’s claim is even stronger. She writes that Roy is of the conviction his own work “falls well within the framework” of the ISR’s ZfS and its approach to social research—something affirmed by both Gottschalk herself and August Thalheimer (1884-1948), a close friend of Roy’s and one of the leading theoreticians of the KPD since the early 1920s, editor of Die Rote Fahne, later expelled from the party in the Comintern’s purge of the left-opposition in 1928/29. On discovering and reading Gottschalk’s letter for the first time, I was also convinced of this—and it’s to the end of a closer comparative study of Roy’s work and the ISR’s research program that I’ve translated the letter and transcribed the enclosed book outline and fragments.

The fragments are experiments in the application of non-dogmatic Marxism to the critique of Neo-Kantian and positivist dualisms in the most recent developments the natural sciences, especially the confusion introduced by the development of non-mechanical quantum mechanics. By the last fragment ([Fragment 24: 20.7.36.]), Roy has already arrived at an independent formulation of the idea of ‘critical theory’ in terms as clear as any of the ISR’s leading theoreticians: “I am almost prepared to say that Marxism is not a body of doctrines, but a system of method…” Like the ‘Frankfurt School’ theorists of the 1930s, Roy not only considers the antinomies of scientific inquiry (mechanism and teleology, material and immaterial forces or causes, empirical observation and rationalist deduction, etc) symptoms of a generalized crisis of capitalist society, but proposes a materialist corrective to these problems through immanent—rather than ‘internalist’ or ‘externalist’—critique of the natural sciences understood as historical forms of human social practice.

There are two aspects of Roy’s preliminary sketches for The Spiritualist West in particular that could have made a unique contribution to the development of early critical theory. First, Roy’s program would take the fight to the ‘hard’ natural sciences, and to do so by starting from the conflicts natural scientists already have with one another in the interpretation of results of their shared practice. The goal of the project is to disclose the social content of natural-scientific paradigms like the ‘Copenhagen interpretation’ of quantum physics, presenting them as compromise formations of, on the one hand, the self-uncomprehending demystification of the rationalist enlightenment and, on the other, the revival of metaphysical chimeras this provokes. Second, as a project of ideology critique, The Spiritualist West would have had not only a universal significance but a global scope. The provisional title, The Spiritualist West, is the crystallization of Roy’s thesis: “Western Civilization is not ‘materialist.’” ([Fragment 2: 23.12.1933.]) For Roy, this thesis opens a fight on two fronts: first, against the Indian deference to the ‘materialism’ of the West, to its inherent scientific and economic superiority in relation to Indian backwardness and spiritualism: “Indian intellectuals are suffering from inferiority complex…” ([Fragment 20: 22.1.36.]); second, against the Western deference towards ‘Eastern Spiritualism,’ or India’s “Spiritual Message,” as a corrective to the vulgarity of the West which is supposed to have lost its spiritual substance. As Roy argues in the outline for the book, “The West does not need India’s ‘Spiritual Message,’” and India does not need the ‘materialism’ of Western civilization. For Roy, we have never been materialist: “Indian Philosophy and Western Idealism (No difference).” Roy’s parallel studies in the history of Eastern and Western philosophy are dedicated to exposition of the common “idealistic foundation” of the materialisms of Sankhya and Epicurus, the Vaisheshika system of Kanada and the atomism of Democritus ([Fragment 1: 9.1.1933.]). In the last fragment ([Fragment 24: 20.7.36.]), Roy goes as far as suggesting the incompatibility of the current state of physics with the concept of matter itself, which still has too much of the residue of the metaphysical faith in the idealistic notion of immaterial substance.

As far as I know, though Roy’s writings from prison were repurposed for subsequent books on materialism (Materialism: An Outline of the History of Scientific Thought [1940]) and a collection of excerpts from his prison writings (Fragments of a Prisoner’s Diary [1950]), The Spiritualist West was never executed in the form outlined below. Neither of the collaborations Gottschalk proposes to Horkheimer—neither the suggestion that the Institute publish Roy’s work, nor the creation of an Indian Institute for Social Research—came to fruition. However, Roy’s distinctively anti-imperialist, critical-theoretical approach to the antinomies of ‘hard’ natural-scientific theory in the early 20th century fulfills a number of desiderata of the ISR’s own research program which, despite its scientific ambitions and mid-1930s self-conception as a scientific international, the Institute never did. This alone seems to warrant a closer look at the materials below as an index of the unfulfilled potential of the research program of early critical theory.

—James/Crane (5/24/2025)

Letter: Ellen Gottschalk Roy to Max Horkheimer (August, 1936).

[Ellen Gottschalk Roy to Max Horkheimer, 8/4/1936.]9

Dear Mr. Horkheimer,

I am the wife of Manabendra Nath Roy, who for the last five years has been in prison in India and is to be released this autumn or winter. In all likelihood, he will not be able to leave India, and, in that case, I will go to him there. It is in connection with the work he has accomplished in prison and will accomplish in the future, as well as the trip [to India] I have planned, that I write to you now.

From the beginning of his imprisonment, it was clear that he could only bear the physical and psychic hardships of a “rigorous imprisonment”10 in India if he concentrated all of his energy on a major work. This, he has done—and, with the help from a number of friends, since the first weeks of his imprisonment in July 1931 I managed to regularly procure for him the more fundamental and most recent works in the fields with which he wanted to engage. While in prison, he has come into possession of quite a respectable library of his own. You will be able to see the fields he deals with from the enclosed table of contents for the first book, the basic outline of which he has had completed since the end of 1934, and from the extracts I have made from his monthly letters so far as they pertain to his work.

It is now a matter of completing and evaluating—in other words, publishing—this work following Roy’s release and, of course, a long period of thorough revision. He expects that this work can officially be published in India, but he is keen on having it printed in the West as well. He is of the opinion—and Dr. August Thalheimer has made the same suggestion of his own initiative, and will write you separately about this matter—that his work falls well within the framework of your journal and research work, and therefore I ask that you give some thought to how you might take up his work and promote its implementation in a form which would be useful to the Institute.

Since Roy cannot send out the manuscript before his release, there cannot, of course, be any discussion of a contract or similar obligations on your part. Nevertheless, I believe that from the enclosed fragments, you will be able to tell whether you have a principal interest in Roy’s work, particularly since he is not unknown to you personally.

Where the realization of work that would be of interest to the Institute in India is concerned, Mr. Eduard Fuchs spoke to Mr. Pollock several years ago about my potential activity on behalf of the Institute in India, and at the time I received a letter from Frankfurt confirming a quasi-contract.11 Today, it need no longer be just a quasi-contract. If you wish, Roy will be able to accomplish some truly important work for you there [in India]. He writes that he certainly expects to interest and recruit significant Indian scientists for an Indian “Institute for Social Research”12 and perhaps even establish a university. In consideration of this situation—and, additionally, because he has now concentrated so strongly on this scientific work—he will devote himself completely to this activity for the next few years. He would attach great importance to [establishing] a “publishing department,”13 as there is such a serious want of modern scientific literature, and even of certain kinds of belletristic [literature], that in time one can expect such a publishing house to be successful; founding such a publishing house has been his plan for many years now in any case.

This is the main part of my letter, and I would ask you to inform me of the following: firstly, whether you are in principle prepared to negotiate the publication of Roy’s work as soon as he is in a situation to get the manuscript into your hands; secondly, whether the idea of an Institute for Social Research in India interests you, and, if so, whether your Institute might decide to provide funds for it. (I am sure this would require some rather large sums.) On the other hand, from the standpoint of Marxist research, there is an entire area of sociological and adjacent studies which is as good as unexplored, and for which Roy is certainly a competent expert.

The third and last point of my letter concerns me and my trip to India, and is to be considered entirely independent of the other points. I am an American citizen, the daughter of a naturalized American (and the sister of your secretary).14 As I have never been to the USA and the regulations concerning Americans living abroad have been tightened, the American consulate in Paris is refusing to renew my recently expired passport. I am required to make a special request and provide a particular reason for my continued stay abroad. Since I have already explained to them the impossibility of my immediate return to the USA because I have to travel to India, and since a friendly consular officer has brought to my attention that, due to the recent extension of the “colour-bar”15 [act] to Indians, I would most certainly be unable to acquire a passport if I stated the actual facts of the matter—a formal contract to represent your Institute in India or to establish a branch there or to accomplish some such kind of work for you would be of the utmost value to me. I kindly request that you send me a formal confirmation of such a contract, as the old letter from Frankfurt in 1931 is no longer valid. I need not assure you that this does not require any commitment from you, while I, for my own part, will commit not to make any use of it unless you yourself would place value in having someone work for you in this capacity. Such work would of course be quite agreeable and important for both Roy and myself, and I am also firmly convinced that we could accomplish very useful work for you there. By the way, I have been assured at the consulate that with such a contract from your Institute, I could easily expect to have my passport renewed for at least another year. It would be especially meaningful to me if you could send such a generous and important letter of this sort—in addition to a separate answer, of course, to this letter, for the length of which I apologize. …

Fragments from M.N. Roy’s Prison Letters. Edited by Ellen Gottschalk Roy (1/9/1933-7/20/1936).

[Fragment 1: 9.1.1933.]

I have much to write about what August had to say in your last letter, but cannot do it now. Only one or two remarks. Sankhya’s affinity with Epicurus is in the idealistic foundation of both. This might be startling, but I find Epicurus sacrificing physics for metaphysics (rather ethics) much more consciously than Marx and others thought. As regards Sankhya, he is undoubtedly no materialist, and his idealistic deviations hang in the air, so that we can take much of him critically. Charbak is practically all lost. I am making some efforts to reconstruct from what can be gathered from his opponents, particularly the medieval scholastic and theologian Sankara. But the corner-stone of materialism in Indian philosophy is to be found in the Vaisheshika system of Kanada—one of the six main schools, and extant in the usual Indian aphoristic form. Kanada, approximately a contemporary of Democritus, expounded a sort of atomism, and his Brahaman has no more a real existence than the creator in the system of Descartes or Newton.

[Fragment 2: 23.12.1933.]

The book on Western Philosophy is nearly complete. I have named it Spiritualism of the Western Civilization. It is divided in three parts: Christian and Medieval Thought; Modern Philosophy; and the conclusion of the survey in support of the thesis that the Western Civilization is not “materialist.” Although its size (manuscript is about 600 pp) precludes its being an introduction to the “Outline of the History of Scientific Thought,” it cannot be of great use as an independent treatise. It shall have to be somehow related to the other. I am not yet sure how. Some progress has also been made on the “Outline,” but it is held up yet by the lack of the latest scientific works which I am expecting soon. All of these things will have to be given the finishing touch in conditions when I shall be free.

[Fragment 3: 21.4.1934.]

I would ask August to give me some points on Heisenberg's theory of uncertainty and Bohr’s doctrine of free will based thereupon. I have been writing something on these matters. As far as I see it, the latest discoveries in the field of electronic mechanism have cut the ground out from under the tendencies of the theory of uncertainty. The formula of this Göttingen chap seems to have dispelled the impression that the quantum theory upset mechanics. I badly need some books on this point as well as on the latest biological theories. Haldane’s volt-face is amazing; and Lloyd Morgan’s self-contradiction is pathetic; so is the teleological atavism of Thomas Hunt Morgan. I have got entangled in these things in order to refute the foolish Indian notion that Western philosophy (official) is materialist. I wonder if August will find time to make some suggestions.

[Fragment 4: 17.5.1934.]

You will be glad to know that I have resumed the work on my books. Before my transfer to Almorah I had to suspend it for several months owing to the state of my health. Had I stayed at the old place, the heat would have held up the work another 4 or 5 months. The first book—to dispel the legend of “Western Materialism”—may be finished very soon. It is already ⅔ done. It will be an expose of the various schools of modern philosophy on the background of a broad outline of medieval and antique thought. The introduction to the projected, and partially done, book on Materialism has swollen to the proportion of a separate book—this first one to be completed. The third and the main work on Indian Philosophy still remains in the embryonic stage. But should I have to serve out my whole term, that would also be done, I presume. In any case, an exposition of the point of view from which the vast, mostly unexplored, field will be investigated, and of the method to be employed in that investigation, is a preliminary necessity. Half of the projected work will be done if I can accomplish this preliminary task. I know that the friends abroad would prefer my doing the work on Indian philosophy first. But the exigencies of the situation in this country has persuaded me to reverse the order of my projected work. It is not enough that I have a correct view of the past as a guide for the future. Others must share the view. For this purpose, it is necessary that the method for acquiring that view is available to those objectively moving in that direction; and the acceptance of the method is conditional upon a certain amount of spade-work which may appear rather superfluous to the friends abroad. But what is commonplace to them may be a terra incognita for others, and these babes in the wood are my special charge.

[Fragment 5: 9.6.1934.]

What I wanted to know regarding Heisenberg’s theory of uncertainty is not about [the theory] itself, but what its present position is in light of the latest discoveries of sub-atomic mechanism—of the Curie-Joliots, of Bridgeman, Bainbridge, etc. In the book of the “Spiritualist West” I am just on the point of finishing: Jean’s “Mathematical God,” Eddington’s mystical metaphysics, and Bohr’s mutualism naturally occupy a large place, and these are directly or indirectly based upon the theory of uncertainty. Therefore the explosion of this theory, which claimed to upset the orthodox mechanism of physics, is a staggering blow to the neo-mysticism of contemporary philosophy. Therefore, I am interested to know exactly what position this theory still occupies. Of course, the facts about the peculiarity of electronic movement are there. The only thing to be done is to find a connecting link between this fact and the older laws of motion. It appears that this has been supplied by Born of Göttingen; but I am rather sketchily informed about Born’s theory. All I know is that he has shown that the quantum theory equates with the old mathematical formula of Maxwell. This should enable Einstein to full in the gaps in the tentative theory of the United Field. The harmony of universal mechanism will be reestablished. Some accurate data on these points of the latest physical theories is necessary to round up my criticism of neo-mysticism. Of course, keeping in mind the intellectual level of the readers for whom I am writing, technicalities are excluded. Therefore, I want only general information. I would have liked very much to send the manuscript for August to read, but it cannot be done, for more than one reason. Having been written in extremely unfavorable circumstances, the manuscript is in a disorganized shape, partly in notes that can be transcribed in the final form only by myself, but that technical work I shall not do now.

[Fragment 6: 18.7.1934.]

I am excited about still another thing—apparently innocuous, but of profound significance. It is directly connected with my queries about the present state of the theory of Heisenberg. I just read about a new book, The Atom, by one Dr. John Jutin—which seems to have upset the apple-cart of “Indeterminacy.” I don’t know who is the bull in the China shop, but he is highly certified. In an introduction, Soddy endorses the contents of this book. Curiously, for a whole year I have been sort of vaguely speculating that the inner mechanism of the atom may be somewhat different. Otherwise, on the showing of the “Copenhagen School” (Bohr, Heisenberg, Schrödinger, etc.), determinism appeared to be in a bad plight. Of course, there was absolutely no reason for the philosophic extravagance of Eddington, Jeans, etc. Yet there was a problem to be solved. Determinism could not stand as a dogma. Now I am startled to learn that the thesis of the new book is that Rutherford’s atom—which travelled to Copenhagen for shocking interpretations—is a reversed picture of the reality. That settles it. The problem is solved. I am excited because I vaguely looked for the solution in the same direction. I thought there was little use in engaging in a verbal combat with the neo-mystics so long as they stood on a plausible scientific basis, although they could easily be dislodged from that position with the help of logics. Yet the decision must come from exact science. I shall be very glad to get the new book. I have written a fair amount on the point, and now with the help of Born’s mathematical coordination of the quantum theory with the Maxwellian law of electromagnetism as well as the observational result set forth in the work of Jutin, I shall be able to round up my critique of neo-mysticism. But unfortunately, just at this moment I cannot write. Only an Einstein can carry his laboratory under the hat. It is impossible for an amateur like myself. I cannot develop my thoughts in a coordinated form unless I put them down on paper. And it gives headache to carry the load.

[Fragment 7: 23.8.1934.]

I have used the interval, when I was deprived of all writing material, on thinking out certain philosophical problems to be handled in the books. I am ready to debunk this “New Epistemology” which is supposed to result generally from the so-called “new” quantum theory (of the Copenhagen School) and particularly from the theory of indeterminacy. Apart from the mathematical formula of Born, and experimental evidence provided by the researches in the Cavendish Library, etc., I am in a position to show, philosophically, that Heisenberg’s theory does not run counter to the basic principles of materialism. As a matter of fact, Schrödinger’s wave theory of matter, which is considered by the neo-mystics to be an elaboration of Heisenberg’s principle, is just of the contrary nature. It builds a bridge over the supposed unbridgeable rift between the classical theory of electromagnetism and the quantum theory—a bridge the skeleton of which was laid down by Bohr himself as early as 1913. I mean his “Coordination Principle.” And now old Bohr has come out as an apostle of Free Will and absolute dualism! All tommyrot. So much so that even Bertrand Russell cannot digest the doctrine, and has pointed out that it is all a matter of wrong interpretation. “Indeterminate” does not necessarily mean “undetermined.” That’s what Russell says. If he moves in this direction, there may be a split in the school of “meta-mathematics” which supplies the piece de resistance to this orgy of neo-mysticism. For Whitehead is all for it. Another problem that I have been concentrated upon in these weeks of leisure is Whitehead’s “Philosophy of Organism.” A pure subterfuge it is. It reminds one very much of the famous “Empirio-Critics.” To find a scientific view of nature which would be neither materialism nor idealism, but superior to both! But Whitehead’s “Organism” is either matter or immaterial force, with all his neo-scholasticism and metamathematics, he cannot prove it to be anything else. So, you see, as soon as I can write again, one book will be done directly. About publication I don’t know whether it would be of so much interest abroad. It is written for the Indian reader, and all the criticism is primarily concentrated upon certain basic trends of modern Indian thought. Of course, incidentally, it covers a much wider ground. Anyhow, it is not an immediate question, that of publication. It must come out first. Of course, some preparatory arrangements could be done, if convenient. The work that will be of general interest, that on Hindu Philosophy, will have to be the last. The second one will be the Outline of Development of Scientific Thought, which may not be something particularly new for European and American readers interested in such literature. Only the methodology may be rather new, and [the] presentation of the facts somewhat different. I should highly appreciate some words from August in this connection. I hope he will find the time.

[Fragment 8: 20.9.1934.]

I am sending, as you wished, the table of contents of the book practically done. Of course, it is not an expose, but I think it gives a fair idea of the thing. Although written with a purpose particularly for the Indian reader, the book has come to take on a more general character. As is evident from the contents, the center of gravity is distributed in two places, in the Introduction and chapter 10, book VI; also chapter 5 of the same book can pass as an independent treatise. This was a difficult thing to do. I had some latest scientific literature ordered direct from England through a bookseller in Calcutta. So I have practically all the material needed. But the problem was to translate pure mathematics into plain human language. How on earth could you explain in a language understandable to the ordinary mortal that Pq-qP should not make zero? Yet, that’s the whole secret of Heisenberg’s theory. Then the difference! Well, the thing is done as best as could be. But it must be submitted to our professor’s expert mathematical test. This is all the more necessary because it contains some criticism of mathematics—rather of the philosophical pretensions of those pure mathematicians who would maintain that the symbols do not symbolize anything except possibly some unknowable metaphysical category. Without censoring the extravagance of pure mathematical abstraction, it is not possible to lay bare the physical contents of the theory of indeterminacy, and show that the gap between quantum mechanics (as elaborated by Schrödinger and Born) and classical mechanics is mostly imaginary—as a matter of fact, invented to provide a plausible scientific basis for the ideological needs of a decaying culture. I am afraid it will not be possible for August to pass any judgment on the inadequate data, but he might feel inclined to make some general observations. Of course, the whole manuscript will have to be retouched before publication. So, there will be plenty of time for its examination by experts. Meanwhile I shall also be polishing it.

[Fragment 9: 25.10.1934.]

With great interest I read the remarks of August. Please tell him that in treating the fashionable doctrine of indeterminacy I had in mind practically everything he has to say, and have gone once more over the manuscript to see what further improvements could be made. I believe I have made a thorough job of the subject. I mean it promises to be thorough when the much needed finishing touches will be added in more favorable circumstances. I hope my mathematical heresies have not shocked August too much. Since writing my last letter I have been reading Russell, and in consequence feel the necessity of stiffening up my critique of the pompous pretensions of pure mathematics—particularly of the Logical School of Russell and Whitehead. Their “neutral monism” is sheer sophistry, and mathematics is harnessed for this trick. This reminds me of an amusing thing: Eddington’s decisive argument in favor of his mystical metaphysics. He says that a consistent materialist should look upon his wife as a complicated differential calculus which he cannot do for the sake of domestic peace. Just think of a great scientist arguing like this!

[Fragment 10: 20.12.34.]

In my last letter I did not write anything about my work because lately not much is being done. It has reached the finishing-up stage where constant references are necessary, and the entire manuscript must be on hand. My present condition imposes restrictions on these facilities. But I have got a fairly good collection of the latest scientific literature to study up. By the way, I did not think that there was anything in the observations of the London friend which required particular reply. I was of course pleased and would welcome any further remarks he wishes to make. Indeed, I would be glad to seek the opinion of others. For example, I should certainly want Einstein to pass over what I consider to be the philosophical consequences of his theory of the “Finite, but unbounded Universe.” In my opinion, the theory does not “abolish infinity” as Eddington says; on the contrary, for the first time in the history of thought, the traditional concept of infinity has been given a meaning. I arrive at this conclusion not only through pure philosophic speculation, but from the analysis of the physical content of the mathematical theory. There are other such points on which I must eventually consult the masters—I mean those who come as such out of the criticism of their theories.

[Fragment 11: 20.1.35.]

The books came, but I have not seen them as yet, nor do I know what they are. Being in German, they must go to the police for censoring. I shall surely enjoy them. For a long time I have had no light literature, last month I asked you to send me some. Lately I have been rather run down—thyroid, it seems; have not been doing much serious work except reading some new scientific literature. By the way, would you ask August what one is to make out of Hans Reichenbach, Professor of Natural Philosophy in Berlin University? He seems to take up a curious position; nevertheless he has something ingenious to say. As a matter of fact, there seems to be a group of physicists and Naturphilosophen who very sharply criticize the mystico-metaphysics of the Jeans-Eddington school, and for the purpose necessarily reject positivism (and consequently Berkelyian idealism). Yet the stop on the roadside and play the ostrich game. They call themselves “critical realists” or “physical realists.” Reichenbach seems to belong to the first group, a very brilliant representative of the second is R.W. Sellars, Professor of Philosophy in the University of Wisconsin, USA. In my opinion we should occupy ourselves with these people. I cannot deal with them critically in by book. It has already grown large. But it would be highly interesting to face men like Sellars and Reichenbach with a few straight questions. This reminds me of something very important. I read in the American magazines that Einstein has written a book. It is called The World as I see it. According to the review, it is really not a book, but a collection of letters, speeches, scientific papers, etc. I am naturally curious to see the world as he sees it. This seems to be a curious curiosity, because for the last two years I have been occupied with the question of what the world really is according to the theory of relativity. My curiosity is aroused by a passage quoted by the reviewer. I want to use it in my book. But I cannot do so unless I understand what Einstein himself really means. Please write to him, perhaps with a word from August also, that I would like to hear from him (through you, directly cannot be done, without foregoing one of our monthly letters) on this point, and mention in what connection I am making the request. The passage in question is: “(My religious feeling) takes the form of a rapturous amazement at the harmony of natural law which reveals an intelligence of such superiority that compared with it all systematic thinking and acting of human beings is an utterly insignificant reflection.” It appears that one could easily interpret this sentiment as support for Jean’s “Mathematical God” or even Laplace’s “World Spirit.”

[Fragment 12: 19.2.35.]

I presume you are expecting something about my work. Well, lately not much has been done. I have been feeling somewhat out of sorts mentally. Hence the longing for some light stuff and company. I have nearly forgotten what pleasant company is. I shall come out more unsociable than ever. I always believed that silence is gold. In the future it will glitter on me like a diamond. Nevertheless, I am leisurely working upon the philosophical consequences of the theory of relativity. In my last letter I requested you to write to Einstein asking him for a clear statement of his views on a certain point. Of course, I am not so much concerned about his personal view, which is likely to be subjectively colored. Yet it would be interesting. Whatever it may be, that would not influence the logical inference to be made from the physical theory. The difficulty is that the united field theory still remains in an incomplete form. In any case, the very latest developments are not accessible to me. But rounding up of the united field theory—final statement of the all-embracing field-law—is vital for definitely establishing the philosophical conclusions following from the entire system of relativity physics. Study of materials has necessitated some elaboration in the structure of the book. Originally I planned to deal with the “Philosophical Consequences” in one chapter. I have altered the plan—the material requires a new section with the title, but divided into 4 chapters: Appearance and relativity (Problem of Perception); Idealism and Materialism; Evidence of Biology; Evidence of Psychology. You will be interested to know that I have been looking into psychoanalysis lately. Freud, Adler, and Jung can be combined into a system which does not suffer from such formula as Father-Horse (which amused you so much). However, Behaviorism and psychoanalysis lay modern psychology open to the kind of criticism which was leveled upon physics as represented by Büchner, Vogt, etc. Indeed we are still atoning for the sins committed by the mechanist of the 19th century. The whole system of present day mystic-metaphysics is based upon the confusion of the right thing with the confusion of the counterfeit current in the 19th century. To clear away this confusion is an important task. I don’t know how far I shall succeed.

[Fragment 13: 15.3.35.]

The books you have mentioned have not yet come. I shall appreciate some light literature very much. As regards scientific literature, I should be glad to have some new publications, such as The New Conception of Matter by C.G. Darwin; The Mechanism of Nature by E.N. du C. Andradel Jeans’ new book Through Space and Time; The Passing of the Gods by V.F. Calverton; Technic and Civilization by Louis Mumford. But no hurry, I am simply mentioning a few which may be sent at convenience.

[Fragment 14: 21.6.35.]

No work was done lately because of the fierce heat… How did you come to think that I shall have something to write about psychoanalysis in my book? It was not included in the synopsis I sent you. But since I have come to see that a comprehensive treatment of the subject matter requires inclusion of psychology in the scheme. And psychoanalysis naturally comes in. In this connection I require some information about [the] literature of Gestalt-Philosophie. What other books can be useful except the works of Koehler and Kofka? I have decided to expand the chapter “Philosophical Consequences of New Physics” into a separate section [titled] “Philosophical Questions of Modern Science,” divided as follows:

Chapter 1: New Physics (Statement of basic theories; Trend of latest research—wave mechanics; continuity of scientific knowledge; relation of the theory of relativity with classical physics; reconciliation of the quantum phenomena with the principle of continuity)

Chapter 2: Philosophical Problems (Main issue raised is Epistemological; Epistemology not the whole of philosophy; ontological problems; Truth; Reality vs. appearance; Unity in Diversity; Physics invades the realm of metaphysics; creation of an a posteriori system of metaphysics)

Chapter 3: Cosmology (Einstein’s theory of gravitation; the concept of Force disappears; Classical mechanism and Deus ex machina; relativist mechanism is self-contained; gravitational force—Least Action—Geodesies; Finite, but unbounded Universe gives a concrete form to the abstract concept of Infinity)

Chapter 4: Space and Time (Absolutist theory finally liquidated; Kantian ideas also set aside; space is a physical reality; space is not a void that contains matter; it is a property of space; time expression of change; relation between time and motion. Space-Time represents Dialectic cosmological conception; Superior to the old mechanistic.)

Chapter 5: Substance and Causality (Electric nature of matter; material composition of electricity: wave theory; unitary conception; elimination of mass-energy dualism; relation of being and happening; being realizes itself in becoming; static view of inert mass replaced by a dynamic conception; simple location in space was an abstraction; no such thing in nature; Everything always in movement; “events” represent substance in movement; causality and probability; not mutually exclusive; determinism is distinct from predestination; causal connection among infinite entities can be stated only in terms of probability—statistically; probability is determinism applied to infinity; elementary units of matter do not exist individually; therefore deep down in the microcosmic world determinism can only be expressed statistically; statistical laws presuppose causal connection.)

Chapter 6: Theory of Knowledge (Epistemology and modern philosophy; positivism; problem and perception; fallacies of the causal theory; mechanistic conception of mind; External world—a misnomer; mind is a part of the “external world”; the machinery of cognition; defense of induction; application of differential law.)

Chapter 7: Dialectical materialism (Mechanical conception freed of fallacies; ontological validity of knowledge proved a posteriori; problem of perception solved; idea of absolute banished; metaphysical reality of matter experimentally proved)

Chapter 8: Evidence of Biology (particularly physiology)

Chapter 9: Evidence of Psychology

Sorry cannot give details for the latter chapters. Shall send a better synopsis, but the paper is finished.

[Fragment 15: 21.7.35.]

Today I complete 4 years of my imprisonment; there remain another 15 or 16 months. The last lapse of this terrible ordeal threatens to be difficult. Even one more year of this life appears to be a dreadful and depressing prospect. It may be too much physically. The change this year has done me no good. Indeed, it has been no change, either as regards climate or attitude. These two months have been grueling and have left their mark on my power of resisting the other innumerable pleasantries of this life—but is it life? There are a lot of rains now, and the heat has lost some of its fierceness. But it has become nasty instead; this damp heat is hateful, especially when one has a very limited amount of clothing—and what clothing?! The clothing gets soaked with perspiration, and everything smells repulsively. Once clothes are washed it may take days to dry them, and meanwhile one must wear smelly clothes. The straw mattress is damp. The coarse blanket of raw wool makes my little musty room smell like China Town. Of course, measured by the standard of comfort permissible to a prisoner, this all may be as it should be. I feel very weak, so much so that often the least exertion compels me to lay down. And the movements for daily routine—washing, bathing, clothing, etc.—amounts to exertion. It seems that the heat has aggravated the dilation of the heart. The pain in the chest remains, sometimes getting rather disagreeable. Last week it was very acute for several days. The temperature again rises slightly in the evenings; on the whole I feel miserable and depressed, worse than ever during the last 4 years. Therefore I am more confirmed in my opinion that death would be preferable to more than 5 years at a stretch of this life. I hope it would not be necessary to make the choice actually; and the joke of it is that you cannot make the choice. One should think that man was free to do whatever he liked with his own life. But, no, civilization does not give man even that much freedom… Sometime back I sent you a list of new scientific books. Try to get these too: History of Science and its relation with Philosophy and Religion by W.C.D. Dampin-Wetham (Cambridge University); Philosophical Basis of Biology by J.B.S. Haldane; Process and Reality by A.N. Whitehead; Science and Human Experience by H. Dingle; Where is Science Going? by H. Levy; What Dare I Think? by Julian Huxley; Philosophical Studies by G.E. Moore; The Metaphysical Foundations of Modern Science. I want very particularly Einstein’s latest which coordinates atomic phenomena with the general theory of relativity. It is published the Review of the American Physical Society. I am terribly keen about this thing, because it bears out my guess which I made in drawing out the philosophical consequences of quantum mechanics. Concretely I have written that “uncertainty” of quantum phenomena would be eventually explained by the application of the physical principle of relativity to the microcosmic world, and that Einstein's unified field theory was moving in that direction of a grand synthesis of modern physical knowledge. I never received Einstein’s book The World as I see it; I hope I shall still get it.

[Fragment 16: 20.8.35.]

Just these days I have been writing about the light that modern scientific research throws upon the old notion of immortality. Naturally the doctrine of the soul has been under consideration. Hence my wondering about the soul of blossoming flower plants. But don’t be alarmed, I am not going mystic, although for the last couple of years I have got acquainted with practically everything that neo-mystics have to say. Modern physicists in search of God—as incredible phenomena of this topsy-turvy period of history. And when clever people set about to defend a lost cause, they don’t fail to make it plausible, though [an] extremely precarious cause. Have you ever heard of “neutralism”? This is Bertrand Russell’s latest; no, I am afraid, the divorce from Dora is the very latest. That chap has an amazing mind. Associated with wealth and the consequent idleness, intellectualism runs wild. If any of the contemporary philosophers takes up an out and out solipsistic position, and guides it by brilliant sophistry, that’s Russell. He is the 20th century Hume, and cheerfully, with blissful irresponsibility, goes much farther than the master. In support of his epistemological skepticism (I should say nihilism) he actually argues that when a physiologist observes the brain of a person, he experiences nothing but some events of his own brain. I should say one must have brain fever to put forth such argument. Yet a lost cause must be defended by every possible means. These doughty defenders of the lost cause are actuated by the maxim: Offense is the best defense. They feel the wall on their back. But they are putting up a splendid fight. No denying that. It is a mistake to ignore them, or judge light-heartedly by our standards. This foolish mistake is committed by the people on the other side of the line. That’s a simple and easy way. But the fact is that neo-mysticism has a nearly untouched reserve to fall back upon. That’s traditional prejudice. No, it is a grave mistake to follow the line of least resistance. The people must be met on their own ground; should be judged by their own standards. It is easy to operate with cliches and quotations, but these don’t carry weight very far. They are conclusive argument for those already convinced; but to others we must speak in their language. Our weapon should be criticism: to expose the internal fallacy of scientific religion. Of course, this requires some time. Fortunately (!) I have had plenty of it. Could do some sound thinking which will have its practical consequences sooner or later I hope. Only, to do the job as thoroughly as I am eager to do, it is necessary to have a whole library of specialized literature, and facilities for systematic research. Even under the most favorable conditions, it would take at least 5 years to execute the plan I have before me. Therefore I should be satisfied if even a third of it were accomplished. The rest? We shall see.

[Fragment 17: 22.9.35.]

But enough of ecclesiastical history, though it is a fascinating subject, and I find great delight in reconstructing it with new materials. The old one I studied in the first year of my imprisonment while I was working upon the projected History of Scientific Thought which, owing to insurmountable technical difficulties, had to be abandoned in a partly finished state; but practically all the materials are collected, to be worked out whenever the suitable opportunity presents itself… Then I had an incidental purpose for studying Ecclesiastical history—to settle an old account with August. We had some differences as regards the value of Medieval learning. He thought that I underestimated the positive contributions of Medieval culture. I think, on the whole, I have come around to his view.

[Fragment 18: 21.12.35.]

Lately, I have been occupied with “Kant-Studien.” No fear of neo-Kantian deviation. It has been in connection with this newfangled “Mind-stuff” theory which is supposed to result from modern physical research, particularly of atomic (quantum) physics, as a substitute for the concept of material substance. I have shown that there is nothing new in this newfangled theory; of course, it does not result from the revolution in the conception of substance brought about by quantum mechanics. It’s an echo of Kant’s a priorism or Leibniz’s monadism mixed up with Berkeleyian subjective idealism. Kant-Studien was necessary to show up Kant against Kant; that the refutation of the modern mind-stuff theory can be found even in the positive element of Kant’s empiricism.

[Fragment 19: 20.11.35.]

Just now I have plenty of books. It took long to get them, but finally I have practically all I need immediately for my work, which, by the way, is progressing well so as to make up for the lapse of last winter and summer. It has swelled up to something much bigger than planned. I am still working on the book, a synopsis of the contents of which I sent last year from Almorah. Its scope has widened so much that the title will have to be changed to Philosophy, Religion, and Science (something comprehensive like that at any rate). The chapter on the “Philosophical Consequences of Modern Physical Research” has grown into a large-sized book—ten chapters. So the entire book has to be in 3 volumes, or broken up into three different books belonging to one series. I have fallen into the fashionable habit of writing trilogies. Well, about this, I shall write on another occasion.

[Fragment 20: 22.1.36.]

Your idea about an Institute for Social Research is splendid. Very valuable work could be accomplished through the aid of an Institute like that. We can easily secure cooperation of some distinguished professors. Affiliation with an University might not be possible from the very beginning. The difficulty is about money. It will not immediately be available from Indian sources. Not much imagination is necessary to realize the far-reaching importance of such an undertaking in this country. The principle work of the Institute must be production of literature in the beginning. That means a publishing department. I wrote you already about my plan of founding a publishing house as the center of an intellectual movement. That is the main thing I shall undertake on my release. Therefore, please go ahead with your plan. Indeed, in this country we must work rather on the line of Malik-Verlag. The cry is light, more light. —Personally, I have developed the mood for scientific work. If I carry on my present plan, several years must be put in. The main work is still to be written. I mean the critical history of Indian culture in general and the treatise on Hindu philosophy particularly. So far I have accomplished only the preparatory part of this undertaking. The books already done will create the atmosphere in which criticism will be appreciated. For the present, Indian intellectuals are suffering from inferiority complex. They have neither the critical spirit of science, nor any sense of humor. Social research and reconstruction of history are done with the purpose of depicting the Golden Age, not that of Jean-Jacques. India’s Golden Age was not an Arcadia. It was sort of ante-dated modern civilization. —For the future, once I am out, it will not be necessary to buy all the books. Then I shall be able to use libraries. There are only one or two things I am very eager to get without delay, and they are not available through ordinary booksellers of this country. The most important is Einstein’s latest extension of the united field theory which he has worked out at Princeton with young Dr. Rosen. Last summer it was published in the Journal of the American Physical Society, of course even for this I can wait. But I am eaten up with curiosity. The reason is this. I have made the bold and unorthodox suggestion that the difficulties (about the problems of substance and causality) raised by the latest theories of quantum physics, particularly wave mechanics and Heisenberg’s doctrine of uncertainty—will be eventually cleared by the application of the physical principle of relativity to microcosmic events. Indeed, I have gone further—to the extent of showing that uncertainty of electronic movement is really a matter of epistemological relativity, and that the apparently antithetical concepts of wave and particle are reconciled in a relativist view of the structure of the substratum of the physical world. Of course, there is nothing new in all these. The results of Dirac’s research, divested of their abstract mathematical form, clearly indicate to this direction. Even Eddington has suggested that the cosmic constant may be the most fundamental physical category. Nevertheless, the mode is to regard quantum physics as a scientific fin de siecle, and relegate relativity to the limbo of classical theories. My contention is, and support for it is found in the scientific view of mystics like Eddington and the works of Dirac, that the theory of relativity takes us deeper into the structure of nature than the quantum theory; the former is a universal principle, whereas the latter deals with a particular problem. In other words, relativity is a philosophical principle representing the sum total of scientific knowledge new and classical. Now, in this latest extension of the united field theory Einstein calls the quantum theory “incomplete,” implying thereby that it will be covered by the extension of the principle of relativity. Thus, in the full text of the new extension I expect to find concrete physical support for the philosophical view I have tentatively suggested. Hence my curiosity, and I dare say it is pardonable.

[Fragment 21: 22.4.36.]

Among the books newly received there is a small Sorbonne publication which must have come from you. I am glad to get it. There are some good things in the series, and cheap too. I shall mention a few which you might send if not very inconvenient. De Broglie, Conséquences de la Relativité dans le Développement de la Mécanique Ondulatoire; André George: Mécanique Quantique et Causalité. De Broglie: Théorie de la Quantification dans la nouvelle Mécanique. These all belong to the series “Exposés de Philosophie de Sciences” published under de Broglie’s direction. By the way, I am curious about the socio-political attitude of this man. He is a “Prince.” Does he belong to L’Action Francaise or Camelot du Roy? That would be a curious phenomenon baffling for the “Philosophie de Sciences.” He is certainly a revolutionary in the field of science. I am convinced he would survive Heisenberg, for example. I wonder if sufficient attention is being given to the philosophical implications of wave mechanics. Since the theory of relativity, no other single result of physical research has had such a profound philosophical consequence as de Broglie’s dual conception of matter. The synthesis of wave and particle is really an epoch-making contribution to scientific knowledge. Proper appreciation of this fundamental fact shows how ridiculous all this bother Eddington & co. are making on the strength of Heisenberg’s principle which is nothing but a case of epistemological uncertainty. This is easily explained by the philosophical implication of the Physical Principle of Relativity. Send me some works of Mangevin, particularly on Determinism and Relativity, if you can manage. He might remember meeting me in 1925.

[Fragment 22: 24.5.36.]

There is another thing I want very eagerly. It’s another paper by Einstein, “Physics and Relativity,” published in the Journal of the Franklin Institute of Philadelphia, March Issue (I think). I never got the paper published last year, the newest version of the united field theory. It’s very distressing. I want these things so very much. Just now I have been occupied with the epistemological consequences of the theory of relativity. Einstein’s new paper seems to back up some of my ideas. Therefore it would be so very useful for developing them. In any case, the finishing touches must wait until I am better situated. Meanwhile I am doing what is possible, and am satisfied with the result, some philosophical stuff. Did you keep up the matter with an Indian Institute? It would certainly be very useful if the old friends could be persuaded to back up the project. It would help me greatly to continue the scientific work to which I shall very probably devote myself mostly, for some time. I want the things I have done published in this country. Some help from the outside would be very welcome. Of course, the main work I have done is not strictly sociological. But it lays down, for this country, the philosophical foundation which is the condition for the sort of sociological research the Institute would carry on. For the absence of guiding philosophical principles, sociological research in this country has amounted to a glorification of the past which precludes a critical approach to the realities of the present, and consequently blocks the road to the future. Besides once I have done with my present work—Philosophy, Religion, and Science—I shall myself take up the more directly sociological work—the critical History of Indian Philosophy. Much preparatory work for it was done already in the earlier days of my imprisonment. So my proposition is quite in the line.

[Fragment 23: 20.6.36]

What about the Institute idea? Could you do anything in that direction? That would be a splendid thing. If some stable arrangement could be made, I would be almost prepared to spend the next 5 years in pure scientific work—to finish what I have begun; and that programme would naturally include a more or less prolonged visit to Europe. So, there is an inducement for Heinz and August. If they really want to have me in the near future, let them get after the idea. I can give the assurance that it would be a very useful undertaking, and I shall put in some solid work—perhaps that would be my lasting contribution. The rest seems so evanescent. Nor will there be anything more pressing or practical to do in the near future. I am reconciled to a long perspective. Heinz was quite correct in his judgment of the situation. The judgment still holds. The situation is very immature.

[Fragment 24: 20.7.36.]

At last, I am in a position to answer the old question: When? definitely. Only the answer will not be very cheering. There remain another 4 months still. Unless something unexpected happens, one way or another (there is not much chance though), I shall be released about this time in November. Four months more than I was ever prepared to stand this life. But your letter has destroyed all my determination. Tomorrow I shall complete 5 years in jail, and when I shall be out four months hence, we shall have been separated just six years. —In addition to what I wrote in previous letters, I wish some preliminary arrangements done for the publication of my books, before you leave Europe. Write to the friends in America to get busy about it. Next month, I shall send some more materials about the contents of the book. But you have sufficient material about the general plan and main contents. The people who have published August’s Dialectical Materialism may also be willing to take up the thing, it being in the same line. By the way, I am very glad that August’s book has been published in English. It is certainly the best popular treatise on the subject. It will be extremely useful in this country, for example. The concluding chapter of my book will be on this subject. It is not yet actually written, though all planned in detail. As a matter of fact, it is being constructed in my mind out of the conclusion drawn, step by step, from the exposition of the philosophical significance of the different branches of science, and critique of contrary philosophical views that are supposed to result from modern scientific theories. I would want so very much to discuss with the friends a whole series of conclusions which may appear to be not quite orthodox. But they are logically unavoidable. Though the charge of dogmatism is overdone, I think it should be met more effectively than hitherto done with gestures of contempt and impatience. However justified these may be, they don’t carry much weight with those who are still to be convinced of the correctness of our philosophy. I have laid particular stress on this point and have found it necessary to criticize the all-too-prominent tendency to catholic conformity. We must have the courage to admit that the last word was not said nearly a century ago, and to realize that certain points may require revision or elaboration or reformulation in the light of the advance of science on which the fundamental principle of our philosophy rests. We should remember what Engels said in his critique of Dühring whom he castigated for shaping a rounded system of philosophy. The “system-shaping” he so severely condemned has become a virtue with the orthodox. Emphasis on the doctrine has all but set aside the method. Yet this is the strongest weapon of our philosophy. It enables us to develop our doctrines consciously, thus demonstrating that a synthesis of all the branches of knowledge is possible only in the framework of a philosophy which is not a closed system and is equipped with a methodology which can logically coordinate apparent contradictions. I am almost prepared to say that Marxism is not a body of doctrines, but a system of method. As regards the contents, I am of the opinion that without abandoning the fundamental principles in the least, it is possible to give up certain concepts. Instead of insisting on terms, we should stand by contents, and thus place ourselves beyond the charge of dogmatism. Those not blinded by stupid orthodoxy must see that the contents of the concept of matter has been found to be very different from the traditional notion. In consequence, strict adherence to the term involves us in a dispute very largely verbal, and a great deal of confusions result from this. We must waste so much time in defining terms. Why insist on sticking to old terms when profound revolution in the nature of their contents has rendered old concepts meaningless and misleading? I have come to the conclusion that our philosophy could be and should be defined as “Physical Realism.” Of course, the classical nomenclature need not be discarded. But, instead of justifying it by an untenable defense of the concept of matter, we might more profitably state in a descriptive term what is the essential principle of our view. I am of the opinion that the term Physical Realism is more appropriate for the philosophy which can coordinate the entire body of modern scientific knowledge into a logical system which knows no finality. And that’s the essence of materialism. As long as the essence is clearly grasped and developed strictly according to original principles, the name can be so extended as to obviate the misleading implication. The adjective “dialectical” does not quite serve the purpose of muling the situation created by the undeniable revolution as regards the concept of substance. It lays emphasis on the methodological aspect, and as such it is very appropriate. But the question remains: what is matter? It has been defined over and over again (I myself have added one) until there is nothing in common between the new contents and the old concept. Yet the association cannot be forgotten. Therefore I suggest giving up patching the old concept with new definitions and adoption of a more appropriate term—for the purpose of explanation. If we stick stubbornly to the concept of matter, and are prepared to modify it in the light of modern scientific knowledge, as our philosophy compels us to do, it becomes very difficult to dispute the logical plausibility of pantheism, for example. I think we should not place ourselves on such a slippery ground. Spinoza was good enough as a counter-blow to monadism or the idealistic miscarriage of Cartesian rationalism. Yet, unless we can take courage in both hands and declare that our philosophy does not stand or fall by the concept of matter, we shall come dangerously near [prima materia],16 or lay ourselves legitimately open to the charges of dogmatism. Don’t be afraid: I am a stern critic of the “mind-stuff” theory. Have torn it to bits. Nor does Heisebnerg’s Neo-Kantianism (I wonder if it is realized that his suggestion is to revive Kantian epistemology) bewilder me. But the fact remains that the disappearance of the distinction between mass and energy demands of philosophy a definition of objective reality which embraces both. The definition: “Matter is that which objectively exists”—simply begs the question. Besides it leads us to dangerous grounds. Other people’s mind’s are parts of the world that exists objectively for me; and mine stands in the same relation to them. We cannot very well go back to the stupidity of Büchner and define mind as secretion of matter. That leaves us holding the baby—an objective mind. What are you going to do with it? If you don’t find a better way out, pantheism lies ahead.

Book Outline—THE SPIRITUALIST WEST: Table of Contents.

Book I. Introduction.

Chapter 1: Ideology of Indian Nationalism. (The doctrine of Materialist West vs. the Spiritualist East—Materialism identified with Capitalism—Historical role of Capitalism—Biological function of life sanctioned by Hindu Scriptures—Profession vs. Practice—Ethical Capitalism.)

Chapter 2: Materialism. (Vulgar and philosophical—Defined by Berkeley—Defined by its protagonists—“Shame-faced” Materialism—Dialectical Materialism—Materialism, Ideology of Revolution—Materialist Philosophy and Practical Idealism.)

Chapter 3: Idealist Philosophy. (Definition—Basic Principles—Comparison with Indian Philosophy—Idealism and Religion.)

Chapter 4: The West rejects Materialist Philosophy.

Book II. Post-Classical “Scientific” Philosophy.

Chapter 1: The Philosophy of the “Unconscious.”

Chapter 2: Positivism and Agnosticism.

Chapter 3: Neo-Lamarckian Vitalism.

Chapter 4: Neo-Kantianism.

Chapter 5: Empirio-Criticism.

Chapter 6: Critical Idealism.

Chapter 7: Neo-Criticism, Fideism, Anti-Intellectualism.

Chapter 8: Philosophy fights Naturalism.

Book III. The “Crisis” of Science.

Chapter 1: Henri Poincaré

Chapter 2: “Physics of the Believer.”

Chapter 3: Symbolism of Helmholtz, Idealist Deviation of Hertz and Religious Prejudice of Boltzmann.

Chapter 4: Spiritualism of Oliver Lodge.

Chapter 5: Oswald’s Energetics.

Chapter 6: Real Meaning of the “Crisis.”

Book IV. Modern and Contemporary Philosophy.

Chapter 1: Pragmatism – Bergson.

Chapter 2: Philosophy of Religious Experience (William James)

Chapter 3: Neo-Kantianism and Neo-Hegelianism.

Chapter 4: Philosophy of Fascism.

Chapter 5: Fascist Religiosity and Mysticism.

Chapter 6: The Cult of the Superman.

Chapter 7: Militant Anti-Materialism.

Book V. Ideological Background of Modern Civilization.

Chapter 1: The West does not need India’s “Spiritual Message.”

Chapter 2: Historical Significance and Essential Features of Religious Thought.

Chapter 3: Jewish Monotheism and Morality.

Chapter 4: Christian Spirit of Renunciation.

Chapter 5: The Idea of a Personal God.

Chapter 6: Irreligiosity and Atheism of Hindu Philosophy.

Chapter 7: Basic Doctrines of Christianity.

Chapter 8: Philosophical Foundation of Christian Theology.

Chapter 9: Christian Mysticism.

Chapter 10: Medieval Christianity.

Chapter 11: Christianity leads the Fight against Materialism.

Book VI. Contemporary Science and Spiritualism.

Chapter 1: Logical Mysticism (Bertrand Russell)

Chapter 2: Metamathematical Metaphysics (Whitehead)

Chapter 3: Romantic Mysticism (Eddington)

Chapter 4: Mentalism (Jeans)

Chapter 5: The Principle of Indeterminacy

Chapter 6: Science and the doctrine of Creation (The law of Entropy)

Chapter 7: Back to Revealed Truth (Critical Survey of Popular Scientific Literature)

Chapter 8: Nationalism and Spiritualism Prejudice (Dewey, Santayana, etc)

Chapter 9: Eminent Biologists cling to Teleology (Thomas H. Morgan, Lloyd Morgan, Haldane)

Chapter 10: Philosophical Consequences of Contemporary Science. (Collapse of mechanical Materialism—Fallacies of mechanical Materialism—It never got rid of Deism—Principle of Relativity—Dialectics introduced into Science—New Conception of Matter—Revolutionary Implications—New Conception of Time and Space frees Categories—Ends the Kantian doctrine of Intuition—Four-Dimensional Space-Time and Materialist Monism—The Notion of Immaterial Force Abolished—Significance of the Theory of Expanding Universe—Corrects the Literal Interpretation of the concept of Finite but Unbounded Space—Discovery of the Origin of the Cosmic Ray clears all Mystery about the Genesis of Energy—Its Material Roots revealed—In Biology—Life no longer a Muster—Growing Amount of Experimental Data—Physiology solves the Problem of Cognition conclusively—The Gap between Perception and the object of Perception disappears—The last Leg of Philosophical Spiritualism Broken—Final Triumph of Materialism.

Book VII. India’s “World Mission.”

Chapter 1: Social Basis of Spiritualism.

Chapter 2: “Decline of the West” (Collapse of Capitalist Society—The Rise of a New Culture).

Chapter 3: Indian Philosophy and Western Idealism (No difference).

Chapter 4: Sanatan Dharma (Eternal Religion of the Hindus).

Chapter 5: Gandhism (The generally accepted form of “India’s Message” – Its social Background and Practical Implication).

Chapter 6: Civilization and Culture (Machine and Man—Conquest of Nature)

Chapter 7: India’s Future (Dangers of Cultural Exclusivism—Modern Civilization is Heritage of Mankind—India must have her share—Forwards, not backwards).

(Manuscript about 1000 foolscap pages, i.e. about 250.000 words)

See: Simon Hajdini, “Dialectic’s Laughing Matter.” PROBLEMI INTERNATIONAL, vol. 6, 2023; PROBLEMI, vol. 61, no. 11-12 (2023), 189-213. [link]

Philipp Lenhard: “It should not be forgotten, however, that during the Second World War, the institute supported more than 200 refugees with salaries, stipends, scholarships, various forms of unbureaucratic assistance, travel costs, affidavits and references.” In: Friedrich Pollock: The Éminence Grise of the Frankfurt School. Translated by Lars Fischer (Brill, 2024), 107.

“I Accuse”: From the Suppressed Statement of Manabendra Nath Roy on Trial for Treason Before Sessions Court, Cawnpore, India. With an introduction by Aswani Kurma Sharma. Published for the Roy Defense Committee of India. New York Office, 228 Second Avenue (1932). [link]

In: Ibid., 11-12.

Roy: “I have relied exclusively upon liberal English thinkers and respectable constitutional lawyers to establish my case. I justify what I have held and done on the unchallengeable authority of Locke, Hume, Bentham, Bagehot, Dicey and even Blackstone. You can not punish me unless you prescribe the writings of these political philosophers and constitutional lawyers as seditious, revolutionary and treasonable. I may be punished nevertheless. I am the victim of a system which knows no other law than the law of coercion and violence. But I may warn this court in the words of another historian of the British constitution. Referring to the case of Hampden, Lord John Russell wrote: ‘The judges in Westminster Hall decided against him but the country was roused and overbalanced by their sympathy the judgment of a court of law.’” In: Ibid., 29-30.

Roy: “I did not make a secret of my determination of helping the organization of the great revolution which must take place in order to open up before the Indian masses the road to liberty, progress and prosperity. The impending revolution is an historic necessity. Conditions for it are maturing rapidly. Colonial exploitation of the country creates those conditions. So, I am not responsible for the revolution, nor is the Communist International. Imperialism is responsible for it. My punishment, therefore, will not stop the revolution. Imperialism has created its own grave-digger, namely, the forces of national revolution. these will continue operating till their historic task is accomplished. No law, however ruthless may be the sanction behind it, can suppress them.” In: Ibid., 28-29.

Christian Fuchs, “M.N. Roy and the Frankfurt School: Socialist Humanism and the Critical Analysis of Communication, Culture, Technology, Fascism and Nationalism.” tripleC 17(2) (2019), 249-286. [link]

“Ellen Gottschalk, 1 Square Leon Guillot. Paris XV2. Paris, den 4. August 1936. Prof. Dr. Horkheimer, ℅ Institute for Social Research. New York.” Sourced from MHA Na [17], S. 16r-18r. Author’s translation.

English in original.

“quasi-contract”: [Quasi-Auftrag]

English in original.

English in original.

See: Horkheimer’s Letter of Recommendation in German and English for Louise Gottschalk (Ellen Gottschalk’s sister) dated 4/19/1937. In: Ibid., S. 36r-37r.

English in original.

In original: [besette materii], marked with “(?)” in EGR’s transcript. It seems to be a variation on the alchemical myth of prima materia.