Collection: The Idea of an Institute for Social Research. Reports 1938-1944.

Between the Self-Conception & Self-Presentation of Critical Theory.

Editorial note. The most substantial part of the below collection consists in transcriptions of the English typed manuscripts for two ISR ‘Reports,’ neither of which (to my knowledge) has been published in English—(I.) the unpublished (for ‘tactical’ reasons, cf. Gumperz-Horkheimer exchange below) draft of 1938 on the ISR’s “Idea, Activity, and Program” and (V.) “Ten Years on Morningside Heights” of 1944, written when the ISR was already effectively dissolved in all but name (since 1941—see this note). Alongside these transcriptions, I’ve included: transcriptions of the course proposals drafted by Horkheimer, revised by the individual members of the ISR, and submitted to Columbia in a last-ditch (and failed) effort to secure teaching positions for the group as a whole in fall 1941 (IV.);1 a translation of Adorno’s unpublished 1941 ‘advertisement’ for the ISR, “A Place for Research” (III.), presumably written in the earliest phase of what the remaining members of the ISR core who survived the dispersal in 41-43 (Horkheimer, Adorno, Löwenthal, Pollock, Weil) would come to call ‘artful begging’ for new sources of funding, an activity that would increasingly monopolize their time between 1940—1946. If the “perspectival distortions” which have overdetermined the reception of early critical theory begin with the under-examined difference between the ISR’s ‘esoteric’ self-conception and ‘exoteric’ self-presentation, the following texts are documents of their efforts to maintain scientific autonomy for the development of a Marxian critical theory of society under increasingly heteronomous conditions of intellectual production hostile to that project.

The clearest example is undoubtedly the intra-ISR ‘Debate’ on social-scientific method (II.), previously translated by Kettler and Wheatland (2012).2 Past interpreters of the internal seminar—Kettler and Wheatland, as well as the editors of the Gesammelte Schriften—have typically read it under the constraints of the narrative of the “long farewell.” They assume a pre-established disharmony between the ‘camps’ supposed to have emerged in the ISR prior to its dissolution, and which are supposed to account for its dissolution: with Neumann representing both the ‘orthodox Marxist’ and ‘empirical-scientific’ side and Horkheimer-Adorno representing the ‘unorthodox’ (if not ‘post-Marxist’) and ‘philosophical’ side. What we see in the discussion minutes is the exact opposite: the ‘debate’ is not about the priority of empirical research or theory, something the participants emphatically agree about, nor about the status of ‘Marxism,’ as they all commiserate about the resistance of Americans to the theory of class struggle in particular. Neumann’s opening caution shapes every contribution to the discussion that follows: “What is crucial is to formulate the explanation so that it is not Marxist.” In response to Horkheimer’s excursus on how their ‘method’ requires the refusal of any strict divorce of ‘theory’ from ‘facts,’ and how this is precisely what distinguishes them from American sociologists, Neumann is unequivocal: “This completely agrees with my views on the matter.” Rather, the ‘debate’ turns on two disagreements: (1) a disagreement about whether—and, if so, which—American social scientists already share their approach (Lynd, Veblen, Shotwell, etc), consciously or unconsciously; (2) a disagreement about how, exactly, they should present their shared methodological approach in order to create the conditions for a shared ‘understanding’ with American social scientists who might otherwise dismiss them as elitist, theory-burdened Europeans who lack the humility for pluralistic, empiricist approaches and as Marxists incapable of ‘value-free’ scientific inquiry. There is a tendency in the reception of early critical theory that seeks to recover unjustly neglected figures from its ‘periphery,’ like Neumann and Kirchheimer, by opposing their scientific modesty and lack of theoretical pretensions to the overvalued figures at its ‘center,’ like Adorno and Horkheimer.3 As much as such recoveries forget the figures of the so-called ‘center’ as scientists, they forget the figures of the so-called ‘periphery’ as theorists—who are thereby forgotten twice over.

Table of contents.

I. An Institute for Social Research: Idea, Activity, and Program (1938).4

Letter—Julian Gumperz, re: “Idea, Activity, Program.”

Letter—Horkheimer’s Reply.

II. ISR Internal Seminar: Debate about methods of the social sciences, particularly the conception of method for the social sciences which the Institute represents. (1/17/1941)5

III. Adorno: A Place for Research (1941).6

IV. ISR Course Announcements (October 1941).7

The Social Psychology of Mass Movements. (Horkheimer)

[Untitled Draft.]

Modern Utopias and their Social Background. (Horkheimer)

Sociology of Popular Music. (Adorno)

Sociology of Art. (Adorno)

Social and Intellectual Foundation of Modern European Democracy. (Marcuse)

The Development of Social Thought in the Modern Era. (Marcuse)

[Draft] Social Thought from the Renaissance to the Present Day. (Marcuse)

History of Modern Political Thought. (Neumann)

Sociology of Legal Institutions. (Neumann)

Sociology of Modern Popular Literature. (Löwenthal)

[Draft.] Mass Culture. (Löwenthal)

Social Trends in European Literature Since the Renaissance. (Löwenthal)

Sociology of Political Institutions. (Kirchheimer)

Development of Criminological Thought. (Kirchheimer)

Two Early Drafts for Course Announcements.

The Role of Ideas in Modern Society.

European Culture in the Twentieth Century.

V. Ten Years on Morningside Heights: A Report on the Institute’s History, 1934 to 1944.8

I. An Institute for Social Research: Idea, Activity, and Program (1938)

I. The Basic Idea.

The center for the study of society has been the university. Special institutes exist for the various branches of social life, economics, finance, demography, and so forth, study that is supposed to be useful for government or industry. The presupposition is that the accumulation and organization of social facts produce results which will be of service to society as a whole. That the administrator, the jurist, and the businessman will benefit from investigations in the social sciences just as the engineer, the chemist, and the doctor apply the knowledge drawn from the natural sciences.

Training and research in the social sciences are strongly conditioned by the idea of this utility. The future industrialists, bankers, and public officials receive one part of their professional training in universities. They acquire not merely specialized knowledge about business and government but also an education in the methods and more general concepts which are necessary for directing roles in society. The professor may have nothing more in mind than the increase and extension of science, but the problems which are presented to him and the knowledge which he must disseminate are largely determined by the interests of his pupils and, beyond that, by the society which awaits benefits from his books.

The situation was not always so. Throughout western history, in antiquity, in the Middle Ages, and in the first centuries of the modern era, the theory of society was closely bound up with philosophy. We need only point to Condorcet and Adam Smith. The theory of society remained a task of the philosophers long after the natural sciences had become independent disciplines. This personal union expresses a real relationship. Philosophy deals with the meaning and destiny of human life, with the conditions of human happiness, with justice and injustice, with freedom and slavery. While the study of human society retained its ties with philosophy, the structure of these sciences was not determined primarily by technical and vocational needs but equally by those interests which are the interests of all humanity.

We do not imply that Plato or Thomas More or Spinoza or Hegel described the relationships of their day incorrectly, or that they were deluded by wishful thinking; their knowledge is no less valid than the knowledge of modern science. Nor do we imply that arbitrary concepts were drawn into their investigations from above, in the way in which some modern sociological systems seek to force their abstract distinctions and definitions upon empirical social science. The content of concepts like justice and freedom is not to be construed a priori but is determined within the context of the tendencies and interests which operate in all human history and without which neither individual nor social activity is comprehensible. Since the perception and organization of phenomena in the decisive philosophical systems of the past were directed less by the needs of daily life, which are external to the process of thought, than by ideas which those thinkers recognized as the highest goal of mankind, their theories were never lost in matters of subordinate importance. The interest in man and his potentiality permeated them and gave them substance. For that reason their writings took a critical and progressive position to the given reality.

There can be no doubt that the process of specialization in the social sciences in universities and institutes as a consequence of modern developments cannot be stopped. That would mean a backward step. The question is justified, however, whether in the future theoretical studies of social problems should still be restricted to those institutions which, because of the very conditions of their existence, are more or less directly bound up with professional needs. The founders of the International Institute of Social Research answered this question in the negative, although they fully recognized the necessity and value of social studies conducted under such conditions.

The effort of the Institute to free theory from the requirements of individual spheres of social activity does not mean the destruction of the interrelationship between science and human praxis, any more than the orientations to the demands of special activities [ensures] their actuality. Quite the contrary. In times like ours it is particularly doubtful whether the fulfillment of so-called practical needs, the prevailing principles of selection, and public success are determined by rational forces. In attempting to solve the problems which are placed before it by the actual needs of industry and government, the study of the social sciences as it is usually conducted today is faced with specific interests and can fulfill most important functions. But that does not prevent this steadily growing work from being distracted from more general human interests to an undesirable extent. The tendency to arrive at concrete results which can at least be verified and retained as a secure possession if they cannot be applied has not always been helpful in the social sciences. This tendency has not prevented us from filling libraries with volumes that contain results which are of little social relevance.

The International Institute for Social Research has set itself the task of investigating society from points of view which are not required by any practical demands or academic custom, but which have been recognized as essential on the basis of certain theoretical considerations. This is not the place for a detailed analysis of these considerations. The significant point is that society is not examined merely as a complex of “objects,” as in the sociology of Durkheim, but as a historical process with immanent tendencies and counter-tendencies. These tendencies can be grasped only if one consciously and actively participates in them through one’s work and one’s interest. The most important of these tendencies is the creation of conditions in which the infinite potentialities of men will no longer be restricted but will be given full freedom to develop for the benefit of the whole of society. Such a development of man is founded in the very nature of human labor and it finds expression in the humanistic, critical, and progressive movements in politics and in all cultural spheres. The history of our era is dominated by the conflict between this tendency and traditional institutions. The revolutions and counter-revolutions are its crucial historical moments and it has once again reached a critical stage in the last few decades.

The outstanding theorists of society have identified themselves in their own time with the same fundamental tendency toward the establishment of a rational totality of human relationships. They have always construed society under this aspect and their theories have exercised a progressive historical function for that reason. Auguste Comte, the founder of modern sociology, already noted that modern specialized science had fallen away from every great historical idea and he expressed his opposition in the most bitter terms. By examining social processes abstracted from general human interests, one does indeed avoid the danger of “subjectivity.” One acquires a pseudo-objectivity, a pseudo-security, and a mass of so-called results. One can present many facts for every assertion. But the science of society breaks down into a series of disciplines and auxiliary disciplines, general and special investigations without a unifying tie. The theoretical basis becomes increasingly problematic. Serving specific functions in the individual branches of practical life, science loses the ability to serve as a guiding force in the organization of human life in a broader sense.

We can clarify the distinction between the theory of society which is held by the Institute and a certain school of social science by giving one example. Max Weber and Max Scheler founded Wissenssoziologie in Germany and it has become a popular school of thought in the western countries. Roughly speaking, the central point of their doctrine is that specific cultural patterns, such as protestantism, rationalism, liberalism, or conservatism, must be analyzed by determining the social groups to which they correspond. The result is the correlation of political, artistic, and religious phenomena to social units with which they are supposed to arise and decline. Since every literary and artistic work, every political and religious idea can be correlated with a specific mode of thinking, and every mode of thinking with a specific social group, this doctrine opened up an endless field for sociological investigation. The fear on the part of sociologists—lest their science not be recognized as a valid empirical discipline, the desire to place it on a level with the natural sciences—fosters this whole approach.

We of the Institute agree that such correlation can be established. Many of the ideas and conceptions of the present belong to specific social groups and will disappear with them. In some cases it is even sufficient to reveal this connection in order to destroy the validity of the given concept for the intelligent man. We cannot accept the conclusion, however, that this search for relationships is a happy discovery which should be pursued with no precise, guiding idea. In order to really perceive the operation of concepts which are bound up with characteristic groups, it is necessary to determine their role in the actual dynamics of history. The investigator must have his own viewpoint and must be conscious of his own interests. If one investigates Germany in the last decades, for example, one will find various notions which belong to the landowners, manufacturers, peasants, or workers. One can trace these ideas back for centuries and correlate them with the history of the appropriate groups without the least concern for their connection with present developments, for the degree to which the modes of existence of these groups and their ideas have made the present dictatorship inevitable or at least possible, or for the psychological tendencies and attitudes with which the liberation movement must be concerned.

Wissenssoziologie might reply that such problems are not its concern but the concern of the historian or statesman, that it merely provides the material just as the physicist provides the material for the engineer and the chemist for the manufacturer. This argument involves a grave error. The needs satisfied by the physicist and chemist make themselves known in precise form through the economy, although the disorder of our present economy affects this relationship so that the development of natural science is obstructed and tends to become one-sided. The need for liberation from the social forms which stand in the way of human progress, for the overthrow of dictatorships where it exists, and for its prevention where tendencies in that direction appear, does not make itself known in any precise form.

The presence of a mass sentiment against such a condition cannot be questioned. It is evidenced by the death-defying opposition in the face of the terror of the authoritarian regimes. The need for theory in those circles is not expressed in a circumscribed demand for specific data and calculations which they would know how to use properly. It is rather the task of the sociologist to assist the progressive forces to find their proper expression. He must take over the naive and inchoate desire of mankind for free development and for a rational organization of society and formulate it in a way which is appropriate for the given historical situation. He must make it the leading idea of his analysis. It is not enough merely to discover and classify the facts within a sphere which was once delimited. The sociologist must see to it that his theory corresponds with the historically decisive problems. Otherwise, it would still be possible to write very learned and penetrating monographs, but it would be a delusion to think that they actually increase knowledge. Knowledge is to be distinguished from a mass of individual cognitions by the fact that knowledge organizes the latter into a pattern that corresponds to the needs of mankind.

When applied to our example of the various groups in German society, this conception of knowledge requires that the exact definition and characterization of the groups as well as the analysis of ideas be made in connection with the problem of the causes and future overthrow of fascism. The material and psychological composition, the complex of interests, the hopes and aspirations of the social groups which have made the rise and duration of the authoritarian regime possible, must be understood against the background of the general economic development. We must investigate the extent to which we are dealing with characteristics that are superficial ideologies and the extent to which they are deeply rooted traits bound up with the real existence of respective groups. The latter are all the more important because they are relatively unaffected by national distinctions. The differences between the cultures of pre-war Germany and Italy were many and sharp, but fascism is bound up with human complexes which existed in both countries, in fact, in all countries where the present form of economy and society prevails. It is of the highest practical value to know these complexes and to analyze them scientifically. That cannot be done by free correlation out of an allegedly disinterested, chemically pure intellectual experience without a leading idea. Such an analysis requires a theoretical approach guided by a concrete practical interest in human freedom. The problem can neither be perceived nor solved without the aim of destroying fascism and of setting up a more rational society in which fascism will no longer be possible because its basis will have disappeared.

The demand that science must stick to the facts, that the concepts be clear and the methods rigid, is self-understood. That is only one aspect of science, however. There is a further requirement that the facts be investigated in a manner which will further human ends, that the proper subject matter be chosen and analyzed in a manner appropriate to the decisive problems of human existence. Bad science is not only that which produces already known or false results, but also science which produces new and correct results that are meaningless for the tasks of the period. It is true, of course, that some scientific activities are meaningless at first and become essential only later, just as some theories can only be proven true after a long time. This circumstance does not destroy the obligation to always keep the essential in mind.

The decisive problem for present-day society is to save mankind and its culture from the dictatorship of industrial and military bureaucracies, to create social forms in which man will really be free and will be able to develop his potentialities happily. There can be no doubt about the deep contradiction which exists between human forces, methods and means of production, material and cultural goods on the one hand and the destiny of most men on the other. An awareness of this contradiction dominates the history of Europe and America in the last decades. There have been many attempts to formulate the problem, technocracy for instance. Everyone is cognizant of the fact that its solution is the task of our time. Man seeks to create universal happiness and wealth by his labor, but in large part, he creates misery and poverty. He desires the development of all individuals and whole peoples, but countless men and even nations fall into poverty and decay. He seeks peace and justice and the world stands under the threat of war and barbarism. This contradiction is no inevitable cross which man must bear like a natural phenomenon. Man has created and renewed these relationships, and man can improve them and ultimately overcome them.

This fundamental problem of human existence cannot be solved without systematic thought. It is merely one of the many problems in the academic disciplines but it must unite all the branches of science which deal with man and society, and their whole conceptual material must be directed to it. The very formulation of the problem immediately faces a sharp and bitter opposition because of its threat to the existing order.

II. The Activity of the Institute.

The members of the International Institute of Social Research believe that the development of a comprehensive theory of society in the sense in which we have sketched it is one of the most important tasks of science today. They do not seek a solution ex vacuo, however, but wish to continue the great western tradition which has been perverted and even destroyed in Europe because of its critical effects. We refer above all to the English and French Enlightenment and to classical German Idealism down to Marx. In order to keep the elements of these traditions alive, it is not sufficient to merely repeat them and apply them to the present scene mechanically. It requires a positive advance through an evaluation of the most advanced knowledge in every sphere. The concepts must be enriched by new experiences and must be adjusted to the changed historical situation. The extent to which an indifferent, static retention of conceptual structures can change their content is revealed by the way the Enlightenment lives on in France, sunk to the level of mere phraseology, or by the use of Marxist terminology in various schools of thought during and after the war. Since ideas tend to become rigid and lose their content, it is the task of scientific thought to preserve their progressive elements by proper theoretical application. Otherwise they run the danger of being perverted by political and other charlatans, a state of affairs which actually characterizes the present cultural situation.

Although the members of the Institute belong to a common philosophical tradition and recognize a common scientific task, they represent various disciplines. They have not decided a priori that social research must be consciously related to the present historical situation but have discovered it from their own teaching and research in various universities and institutions. Philosophy, economics, sociology, history, psychology, and law are all represented in the New York group. [The cooperation of these scholars does not lead them away from their own spheres of specialty in order that they may engage in vague speculations about society or construct new systems and recipes for the salvation of the world.]9 On the contrary, each one continues to work with the material which he is best qualified to handle. But he seeks to coordinate his formulation of the problems and his methodology with the work of his colleagues. Since the various studies are intended to be contributions to the same broad problem, the categories and methodology are adapted to this problem and brought into harmony with each other. The psychologist, for example, continues his research in his own field of investigation of the characteristic personality types is oriented to economic, sociological, and juristic determinants. It is impossible to develop a psychology of the modern white-collar worker, for instance, without a precise knowledge of the changes in his technical and economic function in rationalized, large-scale industry, without reference to the professional organizations [to which he belongs] and their legal position, or without an analysis of the family and the cultural level [of development] in the various countries [in question].

Such investigations are being conducted in many places, of course. The problems have become so complicated, however, that it is most difficult to overcome the disadvantages created by increasing specialization of knowledge. The task has been made easier for the small group at the Institute because its members have a converging interest despite the great variety in their specialized training. Their scientific activity offers proof of this fact, especially in the basic articles which have appeared in the Institute’s periodical, the Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung, and the books which it has published. We present a few examples, including those larger articles in the Zeitschrift (40 to 50 pages) which customarily appear as independent brochures in this country.

The philosophical studies are devoted in part to methodological problems. The members of the Institute believe that the essential in the theory of man and society can be distinguished from the non-essential by dialectical thinking as it has developed in the long history of European philosophy. The following articles may be mentioned:

Max Horkheimer, “On the Problem of Truth.” In: ZfS, Vol. 4 No. 3 (1935), 231-364.

Herbert Marcuse, “The Concept of Essence.” In: ZfS, Vol. 5 No. 1 (1936), 1-39.

Max Horkheimer, “Remarks on Philosophical Anthropology.” In: ZfS, Vol. 4 No. 1 (1935), 1-25.

Max Horkheimer, “Traditional and Critical Theory.” In: ZfS, Vol. 6 No. 2 (1937), 295-345.

Max Horkheimer and Herbert Marcuse, “Philosophy and Critical Theory.” In: ZfS, Vol. 6 No. 3 (1937), 625-647.

Max Horkheimer, “On the Problem of Prediction in the Social Sciences.” In: ZfS, Vol. 2 No. 3 (1933), 407-412.

Other philosophical studies discuss the characteristic intellectual trends of the present day. The prevalent relativism and positivism, as well as their opposite, metaphysics, rationalism, and irrationalism, are analyzed from their common social roots and in their philosophical limitations. Our group has learned from its experience in Germany that the intellectual instability of relativism robs man, and especially the scientist, of his weapons against romantic metaphysics. Rational thinking cannot be limited to analyses and mechanistic methods nor must it fall into metaphysics, which has triumphed in Europe just because thinking has been impoverished by rationalism. The attempt is made to develop philosophical bases for a critical theory of society in which the contradiction between those modes of thought will be sublated.

Max Horkheimer, “Materialism and Metaphysics.” In: ZfS, Vol. 2 No. 1 (1933), 1-33.

Max Horkheimer, “The Rationalism Debate in Contemporary Philosophy.” In: ZfS, Vol. 3 No. 1 (1934), 1-53.

Max Horkheimer, “The Latest Attack on Metaphysics.” In: ZfS, Vol. 6 No. 1 (1937), 4-53.

The economic studies are devoted to current economic problems, though not from the standpoint of the isolated specialist. Their aim is to make the results of individual researches fruitful for the analysis of the whole present-day development. Particular attention is given to those processes which have led to the dominance of large industry, to the development of cartels and monopolies. The structural transformation of the economy, above all the retardation in the tempo of accumulation and the rise and growth of a permanent army of the unemployed, has stamped social life with so many new elements that it becomes correct to speak of a new period in [modern]10 society. The intensified crises and the sharpening contradictions between various groups in society in this period have stimulated efforts to achieve some sort of planned economy on the basis of the concentration in industry and administration. The current methods of planned economy have not created more rational conditions, however—at least not in Europe—, but have brought about a more [rigid rule over]11 the masses. The technical demands of large industry have led to a separation between management and ownership in the means of production. On this basis, there has developed in some of the liberal as well as in fascist and communist states a bureaucratic stratum in the state and industry which stands against the people, conceived as a mass to be organized.

Friedrich Pollock, “Die gegenwärtige Lage des Kapitalismus und die Aussichten einer planwirtschaftlichen Neuordnung.” In: ZfS, Vol. 1 No. 1/2 (1932), 8-27.

Kurt Baumann, “Autarkie und Planwirtschaft.” In: ZfS, Vol. 2 No. 1 (1933), 79-103.

Friedrich Pollock, “Bemerkungen zur Wirtschaftskrise.” In: ZfS, Vol. 2 No. 3 (1933), 321-354.

Kurt Mandelbaum and Gerhard Meyer, “Zur Theorie der Planwirtschaft.” [Preface by Max Horkheimer] In: ZfS, Vol. 3 No. 2 (1934), 228-262.

Gerhard Meyer, “Krisenpolitik und Planwirtschaft.” In: ZfS, Vol. 4 No. 3 (1935), 398-436.

Erich Baumann, “Keynes' Revision der liberalistischen Nationalökonomie.” In: ZfS, Vol. 5 No. 3 (1936), 384-403.

The sociological studies include several in which European and American developments are compared with those in other societies. A few relate to the ancient and medieval worlds, but the investigations into present-day [non-industrial]12 social patterns are more important. In this field, the Institute has devoted special attention to China where the state has been dominated for several centuries by a bureaucratic social stratum that acquires increasing theoretical significance in light of developments taking place in Europe, especially in Germany and in Russia. It becomes clear that the simplified historical division into ancient slave economy, feudalism, and capitalism, which has become traditional in the philosophy of history, must receive more essential differentiation as a result of the theoretical studies in Chinese history. This fact has important implications for the evaluation and prognosis of contemporary tendencies in Europe.

Leo Löwenthal, “Zugtier und Sklaverei. Zum Buch Lefebvre des Noettes’ : ,,L’attelage. Le cheval de selle à travers les âges“.” In: ZfS, Vol. 2 No. 2 (1933), 198-212.

K.A. Wittfogel, “The Foundations and Stages of Chinese Economic History.”

K.A. Wittfogel, “Die Theorie der orientalischen Gesellschaft.” In: ZfS, Vol. 7 No. 1/2 (1938), 90-122.

K.A. Wittfogel, “Bericht über eine grössere Untersuchung der sozialökonomischen Struktur Chinas.” In: ZfS, Vol. 7 No. 1/2 (1938), 123-132.

Other sociological studies are devoted to the development of [modern]13 society as it unfolds in various cultural spheres: politics, art, science, and so forth. Under certain conditions, the analysis of a single work of art can lead more deeply into the inner structure of society than the most elaborate questionnaire with a giant apparatus for investigation and with tremendous statistical results. Furthermore, nineteenth century artists and writers have often made more significant contributions to a knowledge and critique of their time than official sociologists and psychologists. Just as Knut Hamsun contains the elements of authoritarian ideologies, the writings of de Maupassant and Ibsen reflect a tendency to freedom and happiness which points beyond the existing social relationships. Social theory and [activity]14 have more to learn from them than from Spencer or Comte.

Julian Gumperz, “Zur Soziologie des amerikanischen Parteiensystems.” In: ZfS, Vol. 1 No. 3 (1932), 278-310.

Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” In: ZfS, Vol. 5 No. 1 (1936), 40-68.

Leo Löwenthal, “On Sociology of Literature.” In: ZfS, Vol. 1 No. 1/2 (1932), 85-102.

Leo Löwenthal, “Das Individuum in der individualistischen Gesellschaft. Bemerkungen über Ibsen.” In: ZfS, Vol. 5 No. 3 (1936), 321-363.

Leo Löwenthal, “The Reception of Dostoevsky in Pre-World War I Germany.” In: ZfS, Vol. 3 No. 3 (1934), 343-382.

Leo Löwenthal, “Conrad Ferdinand Meyer: An Apologia of the Upper Middle Class.” In: ZfS, Vol. 2 No. 1 (1933), 34-62.

Leo Löwenthal, “Knut Hamsun: On the Pre-history of Authoritarian Ideology.” In: ZfS, Vol. 6 No. 2 (1937), 295-345.

Theodor W. Adorno, “On the Social Situation of Music.” In: ZfS, Vol. 1 No. 1/2 (1932), 103-124.

Hektor Rottweiler (Theodor W. Adorno), “On Jazz.” In: ZfS, Vol. 5 No. 2 (1936), 235-259.

Franz Borkenau, “The Sociology of the Mechanistic World-Picture.” In: ZfS, Vol. 1 No. 3 (1932), 311-355.

Walter Benjamin, “Problems in the Sociology of Language.” In: ZfS, Vol. 4 No. 2 (1935), 248-268.

The historical studies at the Institute are chiefly devoted to the historical derivation of contemporary relationships. The rise of the bourgeois mode of thinking was made the subject of an independent investigation. It was shown that present-day conditions and problems, though they represent a new period in modern society, were nevertheless founded in the very essence of the bourgeois world and can be adequately comprehended only on the basis of the development of that world. The authoritarian state, too, is not an entirely new phenomenon in the [modern]15 era, for the regression to authoritarian forms, mediated through liberalism, had its prehistory in absolutism. Liberty has always been limited by the requirements of the protection of property. Control over the giant means of production in the twentieth century demands a different authoritarian apparatus against the masses than the absolutism of the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries, but compulsion from above is not a contradiction to the spirit of the existing system. Both the absolutist and the authoritarian periods, together with liberalism, are phases of the same necessary development of one economic system. The transition from liberalism to the authoritarian state is not a complete break, as often alleged. This is indicated among other things by the fact that the same figures who formerly dominated industry, and even science as well, still hold that position in Germany and Italy and have even pronounced fascism the correct pattern of liberalism. Mass movements, nation, the struggle for freedom, and leader are categories which are deeply bound up with the position of man in the economic process and his isolation in our epoch. The origin of its modern meaning requires historical analysis.

Max Horkheimer, “Montaigne and the function of Skepticism.” In: ZfS, Vol. 7 No. 1/2 (1938), 1-54.

Henryk Grossmann, “The Social Foundations of the Mechanistic Philosophy and Manufacture.” In: ZfS, Vol. 4 No. 2 (1935), 161-231.

Max Horkheimer, “Egoism and Freedom Movements: On the Anthropology of the Bourgeois Era.” In: ZfS, Vol. 5 No. 2 (1936), 161-234.

Herbert Marcuse, “On the Affirmative Character of Culture.” In: ZfS, Vol. 6 No. 1 (1937), 54-94.

We have already spoken about psychology. Ever since its establishment, the Institute has sought to develop a social psychology which does not play around with a mere enumeration of eternal social drives and instincts or with the establishment of vague analogies between the neurotic personality and the allegedly neurotic society. Instead it attempts to comprehend genetically the characteristic personality structures of the various groups in present-day society. The character type which is typical of fascism and which is the necessary condition for the existence of fascism as a mass movement, the dependent character which is submissive to those above and brutal to those below, is usually conceived as a national peculiarity of Germany or Italy or some other country. This view is completely false. Such [personality characteristics]16 do not arise from national or racial qualities, or from the late adoption of parliamentary government, or from the lost war, but from the dependence and instability of the great mass of individuals under prevailing social conditions. Those characteristics are are linked with the forms of the struggle for existence and with the position of broad social strata, and it is difficult to conceive of a country in which fascist organizations could not tie on to the authoritarian instincts under given conditions such as lasting economic crisis and a strong, threatening labor movement which is [nonetheless] not yet ripe for the fulfillment of its ideals. Various psychological methods, including psychoanalysis, have been employed in studying the mechanisms of this character type.

Erich Fromm, “The Method and Function of an Analytic Social Psychology: Notes on Psychoanalysis and Historical Materialism.” In: ZfS, Vol. 1 No. 1/2 (1932), 28-54).

Max Horkheimer, “History and Psychology.” In: ZfS, Vol. 1 No. 1/2 (1932), 125-144.

Erich Fromm, “Psychoanalytic Characterology and its Relevance for Social Psychology.” In: ZfS, Vol. 1 No. 3 (1932), 253-277.

Erich Fromm, “The Theory of Mother Right and its Relevance for Social Psychology.“ In: ZfS, Vol. 3 No. 2 (1934), 196-227.

Erich Fromm, “Zum Gefühl der Ohnmacht.” In: ZfS, Vol. 6 No. 1 (1937), 95-118.

The investigation of legal problems centers [on] the juristic changes which occur in the transition from the liberal to the authoritarian phase. The key point here, too, is the thought that one essential function of law remains the same in the authoritarian states as in earlier stages of our era. We are referring to protection of the free disposition of the means of production, today in large scale industry as the concern of the actual management, the administrative bureaucracy, rather than of the legal owner. Law had certain progressive, rational qualities in the liberal period which it has lost in the authoritarian state. Law was general, that is to say, it was not directed against specific persons or groups but against specific acts, and it was not retroactive. No one could be punished if the given act was not forbidden at the time it was committed. The judge had to apply the law and not the individual measures of the regime. All these progressive institutions bound up with the protection of property were destroyed in the shift to the authoritarian state. The trends through which this change in jurisprudence was prepared were oriented to a general natural law or to the special discretion of the judge which must be limited by given law. This process of de-rationalizing the law is not unique in the authoritarian state. We need only point to the absolutist doctrines and to the trials during the French Revolution. Characteristic trends in this direction are evident in present-day English jurisprudence as well.

Herbert Marcuse, “The struggle against liberalism in the totalitarian view of the state.” In: ZfS Vol. 3 No. 2 (1934), 161-195.

Franz Neumann, “The Change in the Function of Law in Modern Society.” In: ZfS Vol. 6 No. 3 (1937), 542-596.

This sketch of some of the works published by the Institute, especially in the Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung, aims to show the inner connection of all its scientific work. German has been retained as the basic language of the Zeitschrift. Although it is difficult to circulate the periodical in Germany, it remains an anchor for not a few intellectuals who are in secret opposition to the regime. Scientists and [Politiker]17 find copies in German seminars and libraries, or abroad when they have the opportunity to travel. Furthermore, there [are] a number of progressive spirits throughout the world, Germans and non-Germans, who have the same tradition as the members of the Institute. They are interested in historical problems of our day both theoretically and practically and they are accustomed to retain their ties with this tradition chiefly through German publications. That is not only true of smaller countries like Switzerland, Holland, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and the Balkan States, but even for China and Japan. The Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung is the only independent organ in the German language which covers the entire field of the humanities and the social sciences.

In its publications the Institute is less interested in reporting results of new empirical investigations or in presenting a mass of statistical data than in making its contribution to the preservation of independent, honest, and realistic thinking, the kind of thinking which the authoritarian regimes seek to destroy. A new generation must be trained to apply the most advanced scientific methods and experiences to the burning problems of its time, a generation which will lose its naivete in social questions, which will resist all delusions about the present, and which will have a clear and sharp will to freedom. The Zeitschrift hopes to contribute to this task not only by its leading articles but also by its large review section in which all the relevant literature is discussed. Special review articles have appeared in certain fields, such as unemployment, economic planning, war economy, the social sciences in Germany and Russia, and so forth. The development of a progressive consciousness must combat the tendency, growing out of the present depressed position of the advanced European forces, to evaluate writings about significant political problems not according to their relevance and depth but according to the importance and intent of the author or according to the strength of the party or group from which they stem. An important sector of the once-progressive group of European intellectuals must now depend upon material assistance from political parties and various special groups. Because of the necessity for rapid assimilation and similar considerations, many emigre intellectuals can no longer write freely and independently on social problems, and, ultimately, many cannot even think [independently]. Truth in cultural and social problems has been completely suppressed in the authoritarian countries. [It does not follow from the fact that] it does not face strong opposition [in other countries]. Helvétius once wrote that the truth hurts no one except him who reveals it. This maxim has not lost its validity today. The pressure is great on any progressive thinker, and even greater when he is a guest and cannot shield his untraditional ideas behind a famous name. The Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung has a particularly important role to play in this respect because it is independent.

Whereas the Zeitschrift provides a sort of running account of the studies of the Institute, the results of more systematic work have appeared in book form. The books are naturally devoted to more or less the same subjects as the articles, as a few titles will indicate.

Henryk Grossmann, The Law of the Accumulation and Breakdown of the Capitalist System. Being also a Theory of Crises. 1929.

Friedrich Pollock, Die planwirtschaftlichen Versuche in der Sowjetunion 1919-1927. 1929.

K.A. Wittfogel, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft Chinas. 1931.

Max Horkheimer (ed.), Studien über Autorität und Familie. 1936.

The [last], a volume of nearly one-thousand pages, represents a collective investigation conducted by the Institute into a most significant but neglected problem of authoritarianism. The family is one of the media through which the economic forces affect men and through which the preconditions for fascism were created in Europe. Under fascism the family is simultaneously weakened and artificially [revived]. A detailed investigation of its history in the [modern]18 period provides one key to the understanding of social and cultural relationships within and without the fascist states. This book is the product of a combination of various methods and disciplines, oriented to a common theoretical position. The Institute was able to obtain the cooperation and assistance of many scholars exiled from various authoritarian countries. Through such commissions the Institute has been in a position to aid not a few progressive European students in the present period of emigration, and literally to save some of them from destruction.

A whole series of books in both German and English are now in various stages of completion. Two German manuscripts are ready for publication. One is an extensive analysis of the phenomenology of Husserl, the last great European epistemologist, in whose work all the moments of the decline of idealism and of the self-destruction of independent liberal thought are apparent.19 The other manuscript deals with Luther’s relation to the peasant revolts, a contribution to the study of the leader in bourgeois society.20 The English publications are designed to document the increasingly close ties of the Institute with American institutions and methods.

Otto Kirchheimer, Punishment and Social Structure.21

Paul Lazarsfeld and Mira Komarowsky, The Unemployed Man and His Family.22

Erich Fromm and Ernst Schachtel, German Workers 1927-1931.23

Three volumes of collected articles on social philosophy, epistemology, and the sociology of literature.24

For financial reasons, only the first of these manuscripts has been sent to the printer so far.

Our desire to proceed with our theoretical work as rapidly as possible has necessitated setting severe limits to our teaching activity in America. We thought it most essential to act as a sort of center for all those people, now scattered throughout the world, who are interested in our [common] work. Nevertheless, we were happy to accept the invitation to give one regular course in the extension division of Columbia University. This course dealt with the genesis of the authoritarian state in the history of bourgeois society, analyzed from economic, psychological, sociological, and philosophical viewpoints. The Institute has also organized internal seminars in which a few scholars have been invited to participate with us in our theoretical discussions. It is the aim of the Institute—and its realization has already begun—to choose its assistants from among the best American and European graduate students in the humanities and social sciences, to train them so that they might develop as independent workers in our tradition.

III. The Program.

The program for the immediate future is apparent from the sketch which we have given of the Institute’s scientific activity. The Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung will be made more extensive if possible. The following books will be completed within the next two years, some in English and some in German.

A Dialectical Logic.25 This book will not deal with formal epistemology, but with the material content of logical categories. Scientific-political literature devoted to social problems makes use of categories about which there are wide differences of opinion as soon as one seeks a precise definition. This is true of categories like causality, tendency, progress, law, necessity, freedom, class, culture, value, ideology, dialectic, and so forth. Because such concepts remain vague and equivocal, they are used in philosophy and sociology with seeming precision, although they are actually defined most abstractly or given no meaning at all. Logical empiricism, one contemporary and highly influential school of philosophy, declares these concepts to be completely meaningless. It is true that many of the terms have been gravely misused, often in the sense of a limited and dogmatic metaphysics. The present fashion of discarding them, however, can only intensify our intellectual confusion and helplessness. These concepts have a true meaning, though not one which can be defined with the same words for all times. One cannot treat concepts with definitions in the way in which the Egyptians treated corpses with embalming fluid so that they might last for millennia. Such a desire for certainty cannot be satisfied in the intellectual field. The content of the basic categories of the philosophy of history can be defined only in their precise connection with the historical processes of today. They can be preserved only when one does not embalm them, when one keeps them alive by constantly relating them to changing reality. The meaning of freedom, value, or culture, can be arrived at only when one takes a critical position to the prevailing social conditions, when one reveals the extent to which freedom exists today, and the extent to which coercion, insecurity, anxiety, and impotence exist despite the assertions of the dominant ideology. The definition of philosophical concepts is simultaneously the depiction of human society in its historically given form of organization. The projected book thus conceives a logic in Hegel’s sense, not as an enumeration of abstract forms of thought but as a definition of the major material categories of the most progressive consciousness.

Text and Source Book for the History of Philosophy.26 Traditional histories of philosophy differ from each other according to the emphases of the individual authors, whether they consider epistemological, metaphysical, or ethical doctrines to be more decisive. Past systems and schools are classified from such standpoints. The book which we have projected will approach philosophical theories from social problems and their solutions. Despite the enormous differences, every society in past historical eras has been divided into classes, and the general problems of philosophy are closely bound up with the problems resulting from such a social division. Precise analysis reveals that even in the most abstract theories of knowledge, reason, matter, or man, difficulties and tendencies are to be discovered which can only be comprehended from the struggle of mankind for liberation from restricting social forms. This textbook, therefore, will not be limited to strictly social philosophical problems but will also deal with the problems of so-called pure philosophy. Such an approach will bring to the fore philosophers who are hardly mentioned, if at all, in the traditional histories of philosophy. We might point to the heretical gnostics who virtually disappear behind the early church fathers, the radical Averroists who are hidden behind the Thomists, Adrian Koerbagh, a contemporary of Spinoza, or the pre-revolutionary French thinker, the Abbé Meslier. Success and renown originate in uncontrollable and often hidden forces, not only in society itself but also in the memory of man. This is true of entire philosophical doctrines and of specific aspects. There are many sections within famous metaphysical and idealist systems which are virtually unknown, or are deliberately misinterpreted, because of their critical and materialist tendencies.

The Nature of the Economic Crisis. One of the most significant causes of the ever-sharper crises of the present economic system is the gigantic accumulation of capital accompanied by decreasing possibilities of investment and by a declining rate of profit. The rate of acceleration of productive capital is decreasing from decade to decade. It appears that the capitalist mode of production has reached a point where it is able to make productive use of a smaller and smaller number of human powers. One might say that it is tending toward a static condition, in which the productive apparatus will no longer develop but will merely be reproduced over and over again. This book will show that such a static economy will not be free from crises. The accumulation of fixed capital, particularly in heavy goods industries, is itself a most significant crisis factor because the replacement of used up capital is not continuous but takes place at intervals. Unemployment, the necessity for export to comparatively underdeveloped spheres, in short, the whole imperialist situation leading to fascism will receive a complete reexamination.

Various sociological works have been planned and are now in various stages of completion: a critical discussion of contemporary sociology, a book on the decay of the reception of music. A series of publications on the history and sociology of China is in preparation. In collaboration with the Institute of Pacific Relations, we were able to send one of our members [Karl August Wittfogel] to China where he spent almost three years collecting material of unusual value for the theoretical work of the Institute. Since his return he has begun the organization and evaluation of this material. The following publications have been planned.

Family and Society in China. This book will discuss the various historical stages in the development of the Chinese family—stages which can still be observed in more or less pure form in various parts of China. The character of the change from the Asiatic to the European-American type [of family] is developed on the basis of the cultural differences between the urban and rural population and between the inhabitants of China and the Chinese in Hawaii and the Western part of the United States. The questionnaires which were given to Chinese families in various parts of China and Hawaii were constructed on the same principles as the European and American questionnaires of the Institute. This should lead to fruitful comparative studies.

China: The Development of Its Society. Planned in three volumes, this work will be a development of the fundamental concepts briefly discussed in the article [Theory of Oriental Society]. It departs from traditional studies in this field by giving special attention to the interrelationship among the cultural spheres, economy, politics, religion, and philosophy. The various epochs of Chinese history are discussed in terms of the rise and fall of the specifically Asiatic form of society. The work receives added value from the fact that it provides new material for various fundamental problems in the philosophy of history, above all, the problem of historical periodization. This problem has usually been discussed from material in European history. A study of Chinese society can therefore be very significant not only for an evaluation of the past but also for an understanding of present and future tendencies. Today we see several European states moving in a direction which shows pronounced similarities to the old bureaucratic civilization of China.

Source Material for the History of China. The material which has been collected in China will be published both in the original and in English translation. The chronicles which constitute the bulk of this collection have previously been available only to the highly specialized scholars familiar with the old classical Chinese language, and even they could not make full use of them because this enormous collection had never been properly organized. The publication will require from eight to ten volumes. The project can be carried through only if special funds are made available.

Man in the Authoritarian State. This psychological study27 begins with an analysis of the psychological mechanisms to which the authoritarian propaganda makes its appeal. With the victory of fascism in Italy and Germany many foreign observers were perplexed by the fact that a large part of the population voluntarily submitted to this system, that they allowed liberal institutions to be destroyed and approved of the terrorization of innocent sections of the people. The fundamental reason lies in the fact that the psychological drives which have developed in the modern era are quite compatible with fascist tendencies. The sado-masochistic character can be found in broad strata of our society, not as a mere sexual perversion or as an internal human quality, as is customarily assumed, but as a psychological structure which has come to dominate certain social strata as a result of the prevailing conditions of existence. Men of this type combine a drive for unconditional submission to a higher power with wild aggressive instincts. The analysis of the sado-masochistic character is followed by a discussion of the mass culture of fascism in which it finds its expression. Special attention will be devoted to representative documents, above all Hitler’s Mein Kampf. Hitler’s personality as revealed in this book, and the reasons why it corresponds so precisely to the spirit of broad social strata, have not yet received satisfactory psychological analysis because of the individualistic concept of society and the assumption of eternal instincts which prevail in modern psychology.

The Theory of Fascism. This book will begin with an analysis of that phase of modern society in which the tendencies toward fascism first make their appearance. As we have already seen, it is characterized by contradictions within the national economy and by increasing contradictions in the world market, by the existence of a permanent army of the unemployed, and by growing working class organization. In such times the employers support fascist movements directed against working-class organizations, especially when one section of industry feels itself strong enough to rule over the other sections and over the whole national economy. Where, in a period of severe economic crisis, a highly organized, militant working class failed to seize power and establish a socialist society, the fascist organizations took power with the passive or active assistance from the state apparatus. Special attention is devoted to the reasons why the German working class, the most highly developed of all, was impotent in the decisive historical moment. An important section of the book will compare German and Italian ideologies and institutions. It will be shown that the differences between them are merely superficial. The ideology of fascism begins as an attack on democratic and liberal doctrines. This attack, which sometimes involves the acceptance of Marxist arguments in the form of slogans, is not entirely without foundation. The fascist attempts at a planned economy also constitute a historically necessary process, though in a caricatured and reactionary form. Fascist planned economy does not lead to peace and universal happiness but to the entrenchment of a bureaucracy and to imperialist war.

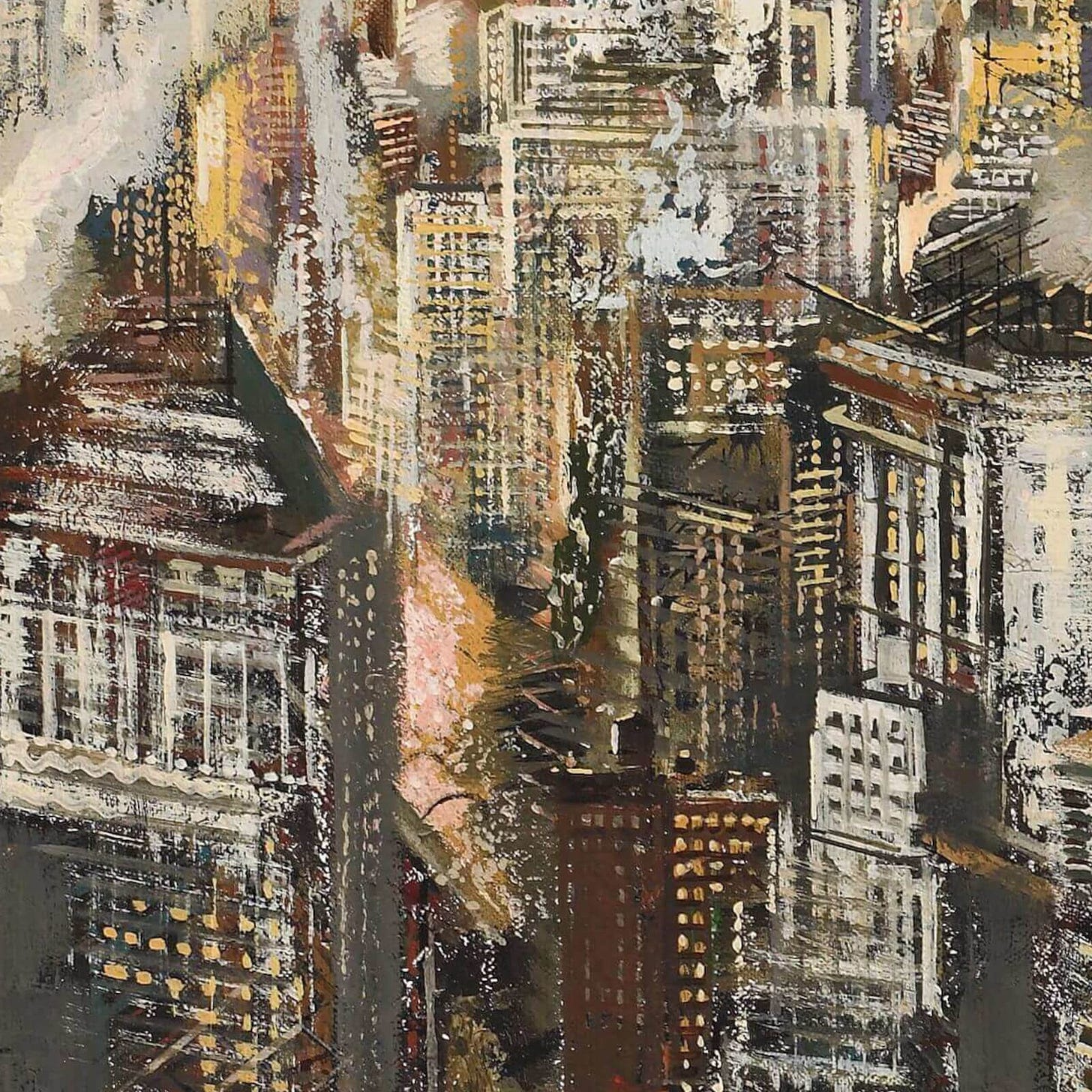

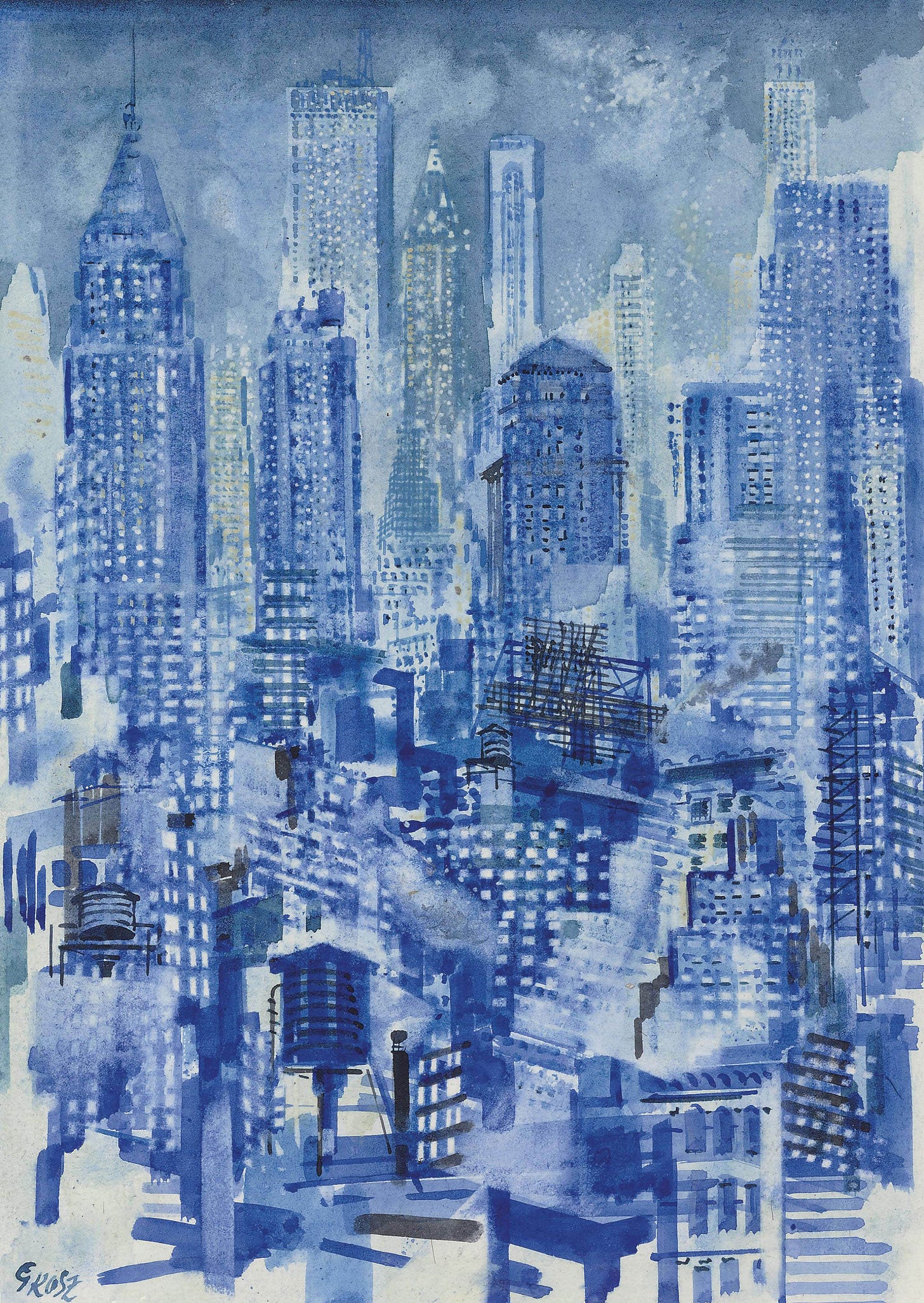

The various books which we have just sketched represent the work of the members of the New York branch of the Institute. We have also supported other works which will be written in Europe by various younger scholars working in close collaboration with us. One large book [by Andries Sternheim]28 will be devoted to an historical and sociological analysis of the problem of leisure time in both the authoritarian and democratic states, including the activity of trade unions, educational institutions, athletic associations, fascist organizations, and so forth. Another work [Walter Benjamin, Arcades Project]29 will analyze nineteenth century bourgeois society in the form of a detailed study of the city of Paris, the typical metropolis of that period. Economy, architecture, living conditions, art, and literature will be discussed in their close interrelationship. Many years have already been spent by the author on this book.

The next few years will not be devoted merely to writing. We think that it is increasingly important that we extend our teaching activity. The Institute’s course at Columbia will be continued and we have planned a series of public lectures. The members of the Institute feel it to be their duty to help spread the knowledge of progressive cultural phenomena. In modern music and painting, for example, one can discover tendencies towards a more rational constitution of human society, toward independence and freedom. The Institute will therefore sponsor lectures on modern music and art by various artists and writers. Our seminars will be continued on a more intensive scale than before. Their function is to enhance the understanding of theorists without whom a progressive solution to modern social problems is not possible. Above all, we shall deal with Hegel, Marx, and Freud.

The essence of the work of the Institute rests in the fact that students of ability and character participate directly. It is high time that they be trained so that they are not more naive about social problems than other scientists are in their own fields.

Letter—Julian Gumperz, re: “Idea, Activity, Program.”

[Julian Gumperz to Horkheimer, 7/25/1938.]30

Dr. Max Horkheimer:

I want to discuss in this letter the exposition of the Institute's work and program, which has been in my possession for some weeks now, and on which I have spent considerable time and effort.

First let me report what has been done up to the present writing. The English translation of the German manuscript was received the end of June. In appraising the translation, I felt the need of comparing it with the original German manuscript, which I have done, sentence by sentence. In many instances I found that the English translation tended to tone down the precision and integrity of thought of the German original. Whether the translator did this intentionally, because he felt that some of your formulations were too near the danger point, or whether he exhibits an unconscious bias, I am not prepared to say. In any case, I have drawn up a separate list of the main and larger differences in formulation, and I have also inserted into the text such smaller corrections as concerned essential points.

In spite of what I considered to be necessary corrections, for conveying the meaning and content of the original, I think that on the whole the translator has grasped the flow of ideas as they came to him from the German manuscript, and has for the most part found a presentable English dress for the German thought. The present English translation is, as far as the English of it is concerned, a commendable and readable document. I think the translator has shown a good command of English style requirements, and it will be necessary only to smooth out certain formulations and to disconnect and connect certain sentences in order to clarify the meaning, and to arrive at a document that is unimpeachable in its use of English.

I have further elaborated certain points that concern the presentation of ideas in the German, as well as in the English document, changes, cuts, substitutions, amplifications, and illustrations, that would contribute to the success of the message, to my mind. But, before conveying all these details to you, I feel that I would want to discuss in all seriousness, with you, the advisability of circulating a document of this nature above the signature of the Institute.

The Institute will live by its work, but it might die by its declarations of faith and the web of words through which it presents its work to a distant and outside world. Scientific work, of whatever description, is in need of a flag that unites its outlying provinces with its center through a binding loyalty. The Institute has as its driving force, as you have so forcibly shown, the common loyalty to a common flag.

The question, however, is whether it is wise to run up this flag for all the world to see. I am seriously inclined to doubt this wisdom. I am more and more inclined to regard the period in which we live, and the years to come, as a time that will challenge all the resources, moral, intellectual, and financial, that the Institute can muster.

I think the world is not any more a battlefield between “Ormuzd and Ahriman.” Darkness is casting its shadows on the world, enshrouding more and more all that is left of the forces of good. Possibly I am inclined to become over-pessimistic, but it seems to me that at least for the years immediately ahead of us, and that concern us because they define our lifetime, the values that emerged as the culmination of a long and bitter process of history are in danger of complete disintegration, and that there is very little hope for their resurrection in the hearts of men as they live today on this planet.

As I see it, one of the real contributions that an institution like our Institute, because of its special position and history, can make, is an attempt to contribute to the sustenance of the life of such values, and to fan the flame of these ideas, even if it burns low or only glows for a long time to come. The world is disjointed. If we could contribute to and assist, even to an infinitesimal degree, the work of those forces that will set a disordered world in order, by such bold announcement and candor as is exhibited in this document, I would not feel my present urge for caution. I do not believe, however, that in the present situation in which we find ourselves, movement still moves. It is the center, the core of existence, that begins to matter now, not the periphery, and although it might be a long time, and it might also be entirely futile, it is the only hope that I see now, that this core and this substance will again some day penetrate to the periphery, where there is action and movement. The Institute should become a path to the cloister that is to be built around this core, and I do not think road posts ought to be erected to direct the destroyers to their goal.

I am not trying to sound an alarm gong, and give voice to the opinion that danger is imminent. But from all reliable signs that have come to my attention and observation in recent months, I have convinced myself that danger is drawing closer. If there shall be war within the next few years, totalitarianism will engulf us all, and the whole world. If there is no war, but the armament race continues, state control, regimentation, contraction of the sphere of individual liberty, will grow more and more, on the basis of a lowered standard of existence for the masses of the population of the world. If a halt is called to the competitive struggle for better and bigger armaments, a world depression will ensue, the social consequences of which might bring about disastrous results.

A document such as the one I am working on now, presenting the essence of the Institute's existence as an authorized statement, might do irreparable harm by getting into the wrong hands at the wrong time. It would not have to be right now, but it might happen at a very inopportune moment three or four years hence, and the consequences might endanger the work that was considered essential at that very moment. I do not believe it necessary at the present writing to elaborate the areas and points of danger contained in this document. If you want me to, I will point them out in a later communication.

At the same time, however, I feel a sense of damage and loss at seeing this superb presentation of the Institute's work and program silenced in the drawers of a file. It should reach the right ears in the right way, without getting the Institute into the danger zone. Sincere friends of the Institute and its work should be called together for a meeting at which you could read this document and give them, after the delivery of the lecture, an abstract in mimeographed form, that could not be misconstrued and utilized to the detriment of the Institute by people who had not heard the lecture and who were interested in the document not because of their interest in the Institute's work but because of their interest in the destruction of that work.

In addition, the printed pamphlet should be rewritten, brought up to date, and re-formulated, so that it may be presentable to a wider audience and at the same time differentiate for them, in the light of your document, the Institute and its work from other social research institutions.

Sincerely yours,

—J.G.

Letter—Horkheimer’s Reply.

[Excerpt from: Horkheimer to Julian Gumperz, 7/31/1938.]31

I cannot now reply in detail to your letter of the 25th. For the moment, it is not urgent, because your practical conclusion that my draft can be used only as a basis for a lecture delivered to a carefully selective audience is exactly in agreement with my original intent. We will discuss everything in detail and organize the meeting with such a select group together. Today, I would just like to thank you for the deep solidarity to which your letter attests. I share in full your concern for the immediate, and also, probably, future, development of historical peoples; that you express these thoughts in concern for the fate of the Institute, in an effort to protect it for as long as possible, is particularly gratifying to me.

II. ISR Internal Seminar: Debate about methods of the social sciences, particularly the conception of method for the social sciences which the Institute represents. (1/17/1941)

Theodor W. Adorno, Henryk Grossmann, Julian Gumperz, Max Horkheimer, Herbert Marcuse, Friedrich Pollock, Felix Weil, H. Weil, Alfred Seidenmann.

Horkheimer: Today, even the empiricists say that one cannot make any more progress through pure empiricism alone. One must draw on theoretical points of view. On the other hand, there are people who dispense with empiricism entirely. Now, the foundations here wish to see projects which might serve as prototypes for a different kind of methodology than that which has been applied in this country up to the present. They expect from us a short explanation of how we conceive the method of the social sciences.

Neumann: What is crucial is to formulate the explanation so that it is not Marxist.

Horkheimer: There is a widespread conception that goes like this: “We poor Americans may indeed be industrious, and know a great deal of facts, and have good methods, but we have no great theoretical thoughts. You Europeans arrive with your noses in the air and act as if you know everything; what we expect from you are theoretical viewpoints and their application to empirical investigations. For example: your idea of class struggle. Show us through empirical investigation that class struggle does in fact have a decisive significance for the interpretation of present social events. This investigation should involve more than the mere collection of materials.’ I (H.) believe this point of view contains an error about the method.

Neumann: The general consensus is: one must have a working hypothesis, but how one is supposed to find it, no one knows; this is a question of preference and attitude.

Horkheimer: You are completely right—this is not our method. What is our method, then? I don’t deny that we confront the material with determinate ideas. This doesn’t distinguish us from most Americans, though there are many Americans who have no ideas of method in general, but only a research program [Untersuchungsprogramm].

Gumperz: This makes matters too easy for us. For leaders in the field, this is not the case.

Horkheimer: In psychological terms, probably not, but in theory, no such ideas are to be found. There is a well-established contempt towards the necessity of the content of the hypothesis, which is considered to fall outside of the field of investigation.

F. Weil: Don’t Americans reject hypotheses and demand an “unbiased” approach to investigaton?

Adorno: As Gumperz said, I believe that the avant-garde discuss hypotheses but the normal American “research men” are supposed to approach the matter “unbiased,” rejecting the hypothesis.

Neumann: This is no longer the dominant trend.

Adorno: In the field of the social sciences, this is certainly still the case. Another trend with which American social science has become especially preoccupied is what they call “content analysis”: one is supposed to begin by analyzing the stimuli which influence the subject. I do not believe this theoretical approach gets us much farther.

Neumann brings up Thorsten Veblen: the great interest in him contradicts Adorno’s thesis.

Adorno: Veblen is considered a heretic.

Gumperz: Nowadays he isn’t. Veblen has become something of an academic God in the course of his lifetime, if in a rather modified and domesticated form, whereas he was previously unable to teach.

Horkheimer: So far as I understand it, “theory” in this case and others like it is such that one first has a hypothesis and then attempts to order the facts on this basis, and then finally takes into account the instances which contradict this hypothesis and reconfigures the hypothesis accordingly.

Neumann: This is a widespread trend. [Robert] Lynd’s Knowledge For What [1939] has already declared war against it. The thesis is: nothing is to be gained from the hypothesis, this is a positivistic method. Instead, one must develop a value-system from out of tendencies within American society.

Gumperz: … this is nothing but a repetition of Veblen’s theory.

Pollock: [Wesley C.] Mitchell has spoken strongly against it.

Gumperz: —but has absolutely spoken in favor of it in his essays and so on.

Horkheimer: How do matters actually look?

Neumann refers to an essay by Max Lerner for an example: “contemporary problems” are configured in a way that enables the structure to come to expression.

Grossmann: We still have yet to fulfill the task of formulating our method.

Gumperz: This cannot be done without the confrontation with other methods.

H. Weil: Each scientist has the longing to arrive at knowledge [Erkenntnis], and on the other hand is bound to the findings of his research. There can be no research without the desire to know.

Horkheimer: Whatever we work out as our method, it will also be contained in the method of American researchers. One cannot make a strict divorce between them. What matters is whether we arrive at a better, more exact determination of our method than others who have also thought about method. To state things rather crudely, I would attempt to draw the following distinction between our approach to an investigation and that of others, particularly those whose approach we find to be alien to our own. It simply would not occur to us to establish a hypothesis because we are already confronted with a completely determinate formulation of the question [Fragestellung]—the question is: is bureaucracy in fact a new form of domination? We do not then say: ‘bureaucracy is the [new] form of domination’ and proceed from there. Rather, we return to the determinate representations we already have about society and ask ourselves: can one even say that something like bureaucracy actually performs domination? Or: is bureaucracy a class? And then we would probably have the tendency to say that what bureaucracy is has to be understood in the first place on the basis of the restructuring process of the ruling class over the last fifty years or so, and that what ‘ruling class’ means is bound up with the conception of economic relations we already have. New facts enter into our investigation in a totally different way. Rather than seeking to collect a series of new facts, we would ask ourselves: what becomes of the concept of bureaucracy when it is filled with the historical content of the last fifty years or so, when it is confronted with the historical experiences of the last fifty years or so? We are capable of doing so because we have a determinate theory, one which unites us. Americans have no similar reserve of theory from which they can draw. This accounts for their perplexity whenever the problem of formulating a theme arises. The problem of method only arises whenever there is no available reservoir of knowledge [Erkenntnis] to speak of (problem of conflict). If we have a determinate representation of what society is and what its tendencies are, no problem would arise if the question were posed: can bureaucratic domination happen in America? —It seems to me, then, that the first thing we can say is that both investigations and the methods applied to them essentially depend upon the extent to which there is already a developed theory of society available.

Neumann: This completely agrees with my views on the matter. The difficulty now is the difficulty of reaching an understanding. The objection will follow: what is it about the theory on which your work is grounded that is correct? This makes it very difficult to arrive at an understanding with an American who does not accept the theory.

Marcuse: The formulation of the question [Fragestellung] lies before us, in a way, in light of a determinate experience. This experience is certainly not the experience that positivists would refer to. So what is this experience we refer to? What have we already learned through such experience prior to the formulation of the question?

Grossmann: We have a theory of class society which is built upon profit. When we take this as our point of departure, the problematic is clear to us. To what extent this is true, we cannot answer. We can either answer with Marx, or we can state that this is confirmed on the grounds of historical experience, e.g., in class struggle.

Horkheimer: Whenever you arrive with proof [Beweis] in hand, you get caught in a circle. The proof always contains elements which are just as questionable. As soon as you bring up decisive experiences, the other will have nothing more to do with it. Bourgeois society could almost be determined by the fact that human beings have nothing but the most impoverished impressions in common. It all comes down to whether you can arrive at an understanding, and when such an understanding has been reached no more ‘proof’ is asked of you. Wherever structured experience is spoken of, this understanding is cut off.