Cultural Aspects of National Socialism (2/24/1941)

The final proposal for the ISR's Germany-project.

Editor’s Remarks: Reconstructing CANS.

“Cultural Aspects of National Socialism” (hereafter: CANS) was the ISR’s final attempt to secure external funding for their long-planned “Germany-project,” which they first mentioned as early as their 1938 program and began drafting in 1939 alongside the earliest outlines for the anti-Semitism research project.

CANS as Compromise-formation.

These remarks directly build off of the introductory editorial remarks published in two previous Substudies posts:

The first of these posts covers the “de-conceptualization” process to which CANS was subjected during a period of intensive revisions under the advisement of the American historian Eugene Anderson; the second identifies the ambivalent concept of democracy as the unifying thread that runs through all of the successive versions of the ISR’s versions of the Germany-project from the Summer of 1939 through the last version of CANS in the Spring of 1941—viz., liberal-democratic capitalist societies have reached a crisis-point in which they are forced to decide between fighting for true democracy or endlessly engendering its opposite: socialism or barbarism. (The specific conceptual idiom the early Frankfurt School used to discuss this historical threshold is the consistently misunderstood notion of “late capitalism.”) Taken together, these points give us a clearer picture of the revision process for CANS: the de-conceptualization of CANS was driven by the attempt to smooth the ambivalence from the concept of democracy at its core.

As Roderick Stackelberg (1987) argues, in every case that significant revisions were made, there was “a weakening of the dialectical notion of National Socialism as a movement that grew to fruition within liberal institutions rather than conquering them from without.”1 This is particularly evident in the revisions to “Anti-Christianity,” one of the most compromised sections, especially when compared to the least compromised sections, Adorno’s “Literature, Art, and Music” and Löwenthal’s “Mass Culture,” which John D. Rockefeller Jr. would, unsurprisingly, single out as particularly offensive.2 As Stackelberg remarks, “if the ostensible aim of [‘Anti-Christianity’ in] the final proposal was to trace the anti-Christian antecedents of National Socialism, the original version advances the suggestion that tendencies within Christianity itself contributed to Nazism,” a task for which Horkheimer originally recruited Nietzsche himself—against the latter’s reception by National Socialism.3 Anderson admonished Horkheimer not to “make it an ideological study […] but use Nietzsche as a manifestation” of ‘Anti-Christianity’ instead.4 Though the final draft of the proposal suggests that Nietzsche’s ideas have been “distorted” by National Socialism to a certain extent, the question of what in Nietzsche’s thought made him on the one hand susceptible to cooptation by the National Socialists and on the other hand the severest possible critic of their “chauvinistic nationalism”—this is removed from the section entirely. Nietzsche is presented as a means by which National Socialism attacked the modern German traditions of Christian thought from the outside, or “the way in which National Socialism tries to mold the religious feelings of the population to its own needs.” The effect of the revisions is precisely the kind of un-self-enlightened enlightenment, incapable of reflexively appropriating the regressive consequences of its self-professed progressive character, that Dialectic of Enlightenment would be written to rectify.

Stackelberg further points out that while the enlightened forces of German social life, and particularly the aspiration to become a modernized liberal-democratic capitalist country, are largely absolved from any responsibility in the development of fascism, Anderson makes the strong recommendation that whenever a proto-fascist or Nazi organization, publisher, or political movement is mentioned—and particularly if the ‘proto-fascist’ outfit in question is quasi-liberal—a “left-wing” example of the same tendencies be listed as well.5 In his study of CANS, Stackelberg effectively subscribes to the “long farewell” interpretive convention of the development of early critical theory in the 1940s—viz., of the ISR core’s increasing isolation, institutionally and theoretically, from both empirical social research and from Marxism. What is unique about his essay is that he treats the revisions to CANS as a microcosm of the ‘farewell’ to Marxism he assumes becomes more or less complete well before the publication of Dialectic of Enlightenment in 1947. The problem with Stackelberg’s study of CANS isn’t that he misrepresents the nature of the compromises made in the revision process, but that his model for interpreting the revisions to CANS as the removal of dialectical ambivalence in fact applies to every single research proposal and report the ISR would author for the rest of the 1940s. To the same extent the ISR feels compelled to perform the same self-censorship in each proposal and report they present to potential or actual American patrons of their work in the 1940s, the purported ‘farewell’ to Marxism never truly occurs. If it had, they would not have needed to make last-minute revisions to the manuscript for Dialectic of Enlightenment in the summer of 1946 removing the majority of references to “monopoly” (capitalism) to avoid accusations of being Soviet agents that were being made more and more frequently in the hostile environment of the postwar Red Scare.6

In a letter to William and Charlotte Dieterle from early March, 1941, when Horkheimer is still optimistic about the chances CANS will be approved by the Rockefeller Foundation, he refers enthusiastically to the “strenuous” but “fruitful” collaboration with Anderson on the revisions and remarks that the process should become “a kind of model” for the ISR going forward.7 In a letter to Adorno dated June 23rd, 1941, written shortly after both CANS and Adorno’s independent proposal submitted to the Rockefeller Foundation for a music-sociological study had been summarily rejected, Horkheimer presents the process as a whole, from the obligatory compromises in revision to the ultimate judgment passed on the ISR’s program in rejection, as an instantiation of the same logic of social control (viz., of the racket) CANS was originally meant to comprehensively criticize:

The rejection of your grant proposal seems to me to constitute proof of the fact that the institute will never be able to expect anything from the “outside.” The sign from on high that even this individual grant is to be denied makes it easy for us to figure out how the board operates. In the decisive meeting in which the project came up someone stood up (or didn’t stand up, as the case may be) and argued something like the following: “We know these people from their time in Europe. Here's a report from our representative based on reports of Mr. Marr, Mr. Salomon, and other Frankfurt University professors. The document is, of course, twelve years old, but what's the record of these people in this country anyway? It only confirms the old testimony that we're dealing with a group of friends who don’t want to let anyone else see their cards and who have little to do with genuine science. They have provided proof neither that they truly pursue social research nor that they want to fit in properly with life here. What we’ve heard about their disreputable mindset is confirmed by their organizational setup. They haven't at all accommodated to local customs, according to which the director of every scientific institution—truly, of every one—and, along with him, the other members of the institution are dependent on a board of well-known businessmen, not only nominally but actually. One doesn't know how and for what purposes money is spent here; one can only guess, based on the mindset of these gentlemen. In any case, I'm against supporting this.”8 The speech probably sounded something like that and consisted of two brief phrases or lasted half an hour, depending on the speaker’s familiarity with the details. —But I view this as the surface. Underneath it is hidden a much more common context: the universal law of monopoly society. In this society even science is controlled by trusted insiders. They are part of the same elite as the economic interests, and the names of scholars in this area do not reappear less frequently than the names of the big directors of industrial advisory boards. Whatever does not absolutely submit to the monopoly—body and soul—is deemed a “wild” enterprise and is, one way or another, destroyed—even at the cost of sacrifices. The judgment that the newcomer is immoral is probably based on the prevailing situation since, with the transformation of a form of human relations, once viewed as beneath contempt, to the characteristic form of society, its characteristics will set the moral standard. We justifiably laugh at the ideologue who speaks about a gang, referring to how it takes control of protection money from laundries in a section of the city, when what’s at issue is “the protection” of countries and control over Europe or over industries and the state. The scale simply does alter the quality. And shouldn’t what is justified for the broadcasting industry and other custodians of the objective spirit be fair for science as well? —We want to escape control, remain independent, and determine the content and extent of our production ourselves! We are immoral. The person who conforms, on the other hand, may even commit extravagances, even political ones, at least occasionally. That’s not so bad and can even be desirable. Occasionally, those who fit in are also served a warning, more for disciplinary reasons than out of fear. Fitting in, however, would mean in this instance, as in others, primarily making concessions, many of them, giving material guarantees that submission is sincere, lasting, and irrevocable. Fitting in means surrendering, whether it turns out favorably or not. —Therefore, our efforts are hopeless, as even appeals to other foundations would be—their variety is just a pretense, and we should be careful about calling attention to ourselves anyplace else. But had this not all played itself out on such a high level, Mr. Marshall would have told you: “Abandon these outsiders quickly, as quickly as possible, otherwise you'll go down with them. I'm advising you to do this with good intentions. If you do it our way, your chances won't be that bad. Now you must do it our way, the orderly, honorable, proper way.” This, of course, is what he actually meant to the extent he had an inkling! —And even the institute as a whole can benefit from this; it just has to deposit its entire endowment, including future income, in a financial institution that is subordinate to a board, not only juristically but also in very real terms, whose members inspire Mr. Willits’s trust. The board would be active in the politics of appointments, in production, and in the liquidation of wealth and would tend to the necessary Aryani– ... I’m sorry! ... the necessary Americanization of the institute.9 Dare we be shocked or even surprised by this? It's all part of the forms in which reproduction takes place during this period. These are forms of domination to which, in terms of their productivity, not only negative but also positive significance is to be attributed. The principle of civilization that we know from history is identical to domination. Their separation is the new puzzle, and we don't know whether and how it will be solved. These theoretical relationships should be preserved even in our reactions that are conditioned by sensitivity. Nil admirari—if one should happen to experience the living conditions of society oneself instead of always only the others doing so. The members of the masses are called “idiots” because nothing is left for them but admirari: respect or hatred, as opposed to the thinking that is found among equals, among patricians. We, of course, find ourselves in an intermediate state that is appropriate for neither one nor the other. Perhaps this was always the situation of theory—even for Marx. ...10

If CANS nevertheless became “a kind of model” for the ISR, it was because they would internalize Anderson’s admonishing recommendations, as well as Rockefeller Jr.’s profound resentment over the implication that fascism could break out in America, in all of their subsequent—and, most often, failed—efforts to find patrons for their work in the United States. When in the Summer of 1944, Löwenthal provided Horkheimer with lists of revisions that would need to be made to the manuscript of the Philosophische Fragmente (the earliest version of Dialectic of Enlightenment), he opened his list of suggested revisions for the most “serious problems” in the content of the text by expressing concern that it was full of “formulations which may bring about the impression that democratic society is everywhere conceived as a preceding stage to fascism.”11 In one respect, Löwenthal’s concern was justified for intra-critical-theoretical reasons: Adorno and Horkheimer’s ambivalent concept of democracy did not maintain that all liberal democracies would inevitably become fascist, but that democracy had been thrown into question between, to the one side, the economic and social crises engendered by capitalist liberal democracies and, to the other, the pseudo-solution or false alternative to actually existing liberalism promised by fascist demagogues. (This is not to say that Löwenthal and Horkheimer always agreed about how to conceptualize or present the connection between liberal democracy and fascism, however.) In another respect, however, Löwenthal’s concern was purely ‘tactical’: an almost word-for-word repetition of Anderson’s critical comments on the earliest drafts for CANS.

While Stackelberg provides us with a model for the self-censorship the ISR would practice throughout the 1940s, the fact that the ISR continued to censor itself so aggressively during that period itself requires an explanation. If the lesson Horkheimer draws from the revision process and fateful rejection of CANS was “the fact that the institute will never be able to expect anything from the ‘outside,’” and, further, that “our efforts are hopeless, as even appeals to other foundations would be,” then why didn’t the ISR begin to moderate its ambitions when drafting future projects? Why repeat the same process whenever the ISR was in need of a new source of external funding?

In a letter dated January 25th, 1945, Adorno informs Horkheimer about the progress he’s made on the application for extending the funding for the Berkeley-study on prejudice (the results of which would be published in 1950 as The Authoritarian Personality), describing his proposed expansion of the study into research on the economic factors of social prejudice, the “objective presuppositions” of the Berkeley-study, as “the implementation of the German studies carried out by the Institute in the first year to the American situation and their continuation with genuinely American material.”12 After the rejection of CANS in mid-1941, the ISR may have given up on sending out new drafts of the Germany-project, but for all of the compromises they were forced to make in revising it, they never really give up on the Germany-project itself.

Reading Key 1: CANS as Critique of Capitalist Social Domination.

The importance of the Germay-project for the self-conception of the ISR (and what would remain of it after its effective dissolution in 1942/43) is clear from Horkheimer’s letter dated March 10th, 1941, to Harold Laski (1893-1950), British political economist and militant Labour-party politician who’d first referred Franz Neumann to the ISR, with both the outline for CANS and instructions for reading it against the grain of its compromises.

Dear Dr. Laski:

The outline of our most recent research project, which I send you here, gives me an opportune pretext to resume contact with you after an unduly long silence on my part. This silence may be partly explained, though not excused, by the situation. Our sad experience that the world is actually as horrid as we imagined it to be, is nowise tempered by the fact that we imagined it this way.

In addition we had a very heavy personal loss to suffer: our staff member, Walter Benjamin, committed suicide after an unsuccessful attempt to cross the Franco-Spanish border. He was one of the most productive men in our circle and, moreover, according to my conviction, one of the very few independent and spontaneous thinkers left. But all this does not imply that we have become passive and gaze into the flames, hands in our laps. You can very well imagine that, in a practical way, we are able to do very little for the time being, except to attempt to pull from the hell of the German orbit as many of our endangered friends as we can. We are making every effort. But the impotence of the individual, and the individual institution, in [the] face of the juggernaut, comes more clearly to our consciousness every day.

So we try to continue our theoretical work tant bien que mal (for better or worse), and to bring our problems as close to reality as possible. Everything that stays aloof appears more superfluous today than ever before, whereas one burns one’s fingers as soon as one snatches at the real questions.

I have attempted to state some of my more basic ideas concerning the present situation in an essay that bears the simple title, “The Authoritarian State” (Autoritärer Staat). For the time being, it remains unpublished. It pursues the line of the article, “The Jews and Europe” (Die Juden und Europa), published in the last German language issue of our periodical. Perhaps it came to your attention. In the meantime, we have started publishing the journal in English, under the title, Studies in Philosophy and Social Science. But it will take us some time before we are able to express our ideas adequately in English—that is to say in such a way that language per se conveys some of the meaning we hope to attach to it.

It appears to me that the matter of the authoritarian state is actually the most important we have to ponder. I visualize authoritarianism as a universal system of repressive domination, aiming fundamentally to preserve obsolescent forms of society by ruthlessly keeping down all their inherent antagonisms. But one has only to set down that it is “important” to ponder this and one sees how grotesque such a statement has become by now. Language, and in a certain sense even thinking, are powerless and inadequate in [the] face of what appears to be in store for mankind.

It is with such a sous entendu and with all these qualifications that I beg you to read our new project on “Cultural Aspects of National Socialism.” Like most of such projects, it had to be drafted rather hurriedly, and the conditions were not entirely favorable. It is influenced throughout by the task set us, to set forth what American democracy might learn from the fate of Germany. The limitations imposed are obvious, yet I hope you will find something in it that will not be entirely boring.

Your last two books circulated in the Institute and have been read with great interest. It is needless for us to say how very much we agree with the conclusions of Where do We Go from Here? We sincerely hope that the historical way out, which you point, will be used not only in England but elsewhere.

Should you find the time to write us a few lines we would be most happy and proud.

—Very sincerely yours,13

In the letter, Horkheimer connects CANS directly to two of the most intransigently communistic texts he would ever author: “The Jews and Europe” (1939), which the council communist journal International Council Correspondence (ICC) helmed by Karl Korsch and Paul Mattick would recommend in 1940 as “the best short exposition of fascism,”14 and “The Authoritarian State” (1942), “which, with its defense of worker’s councils, was perhaps the most politically radical essay [Horkheimer] had written.”15 Though Horkheimer confesses in his letter to Laski that he feels the theoretical perspective offered in these essays—on the development of the authoritarian state from capitalist forms of social domination—is somewhat inadequate in the face of the juggernaut, the fact that he nevertheless claims the same perspective as his own is a testament to what he’d previously called “the most dogged unswervingness [which] is needed not to lose sight of those tendencies of social life which we once recognized as those which are most fundamental through the chaos of facts.”16 Just as much as “The Jews and Europe” and “The Authoritarian State,” CANS is a sign of the refusal of the critical theorists to “become passive and gaze into the flames, hands in our laps,” and to instead fulfill “the task set us, to set forth what American democracy might learn from the fate of Germany.” This is the attitude of understanding with which Horkheimer asks Laski to read through CANS, which, despite the fact that “[t]he limitations imposed [on it] are obvious” in the end result, he hopes Laski will not find “entirely boring.” If the antipathy towards the proposal by the board of the Rockefeller Foundation is any indication, CANS was not nearly boring enough.

CANS as Freudo-Marxism.

In earlier English drafts of the “Introduction” to CANS, the authors write:

[D]emocracy per se by no means guarantees the rights of the demos. […] Since American democracy, though its foundations are incomparably deeper than Germany’s were, may not be entirely beyond this danger, our project hopes to make a modest contribution to American interest. It will analyze the powers that threaten to pervert the consciousness of a democratic people into its opposite. Our approach is based on the conviction that what we have to face is not a fated, inescapable, and irrational ‘wave of the future,’ but is rather something due to social forces open to scientific investigation.

It is only in the earlier German drafts of the “Introduction,” however, that the ISR’s own, unique approach to ‘scientific investigation’ is expressly stated. It is one of the clearest professions of the ISR’s distinctive tack on Freudo-Marxism:

There is no scarcity of scientific contributions to the end of insight into the non-political-economic “issues” of National Socialism. In general, however, these contributions either concentrate on the problem of propaganda or are of a purely psychological kind (e.g., W. Reich’s Massenpsychologie des Faschismus). Without underestimating the importance of the problem of propaganda, we are of the opinion that [analysis of] this alone is by no means adequate to the task of explaining the changes in consciousness of the German people, and, moreover, that it is to a large extent description of a mere epiphenomenon, and that the effect of Hitler’s propaganda on the German people is more an expression of the cultural crisis than one of its decisive causes. The belief that Hitler “seduced” the masses, through advanced propaganda technique, into opposition toward their own interests seems to us naive. Instead, we shall attempt to show the deeper conditions that account for why they fell prey to this propaganda in the first place. To this end, psychological methods—in particular, that of depth-psychology—will be used to a considerable extent. But “psychology” alone does not seem sufficient to us. The Germans who turned to Hitler did not respond merely as individuals, nor even as neurotic, powerless individuals submissive to authority, but rather under the pressure of objective social and cultural forces and in the context of an entire culture of a determinate kind subject to determinate ‘changes.’ Only if we succeed in presenting, on a fundamental level, the interplay between these objective cultural powers and the individuals at their mercy do we believe we can actually, substantively solve the problem we have posed.

In a letter to Franz Neumann dated March 23rd, 1943 concerning the latest draft of the research proposal to the American Jewish Committee (AJC) for funding for their “Studies in Anti-Semitism” project, Horkheimer defends his use of the term “socio-psychological” to describe the ISR’s approach to the problem of prejudice because it gives them the freedom to pursue the same Freudo-Marxist program—viz., investigation of the asymmetrical intermediation of economic relations and psychological formations—outlined in the above-quoted draft of the CANS introduction:

I know very well that you are skeptical with regard to the role of psychology in social problems. Your skepticism is not deeper than mine. On the other hand it looks like the Committee had liked my draft on a “socio-psychological” approach to our subject. I used that awful word because it leaves us a great freedom in our actual research. It also appears to me that the Committee’s fight aims to a great extent not directly at the economic foundation which is inaccessible to its forces, but at human behavior which, though rooted in economic relations, may be influenced somewhat by legislature, education, propaganda, a.s.o. There are at least some so-called psychological conceptions or rather misconceptions which should be analyzed in order to evaluate the Committee’s efforts. What kind of research do you think could do the most good in this direction?17

As Eva-Maria Ziege (2009; 2014) has argued, the ISR’s social research proposals and reports in the 1940s are characterized by the conscious adoption of an “esoteric form of communication” used both to conceal and, to those ‘in the know,’ exemplify a “secret orthodoxy” in their partisanship to “a distinct school of Freudian Marxism.”18 By way of demonstrating the continued relevance of this Freudo-Marxist paradigm for the Frankfurt School following the rejection of CANS for addressing the problem of investigating “the powers that threaten to pervert the consciousness of a democratic people into its opposite” (the basic orientation of their speculative proposals from 1945 through 1949 for postwar German reconstruction), I’ve included my own transcription of Horkheimer’s 1943 review of Richard M. Brickner’s Is Germany Incurable?, “The Psychology of Nazidom.” In the review, Horkheimer criticizes Brickner’s psychologistic misapprehension of the asymmetrical character of the intermediation of economic relations and psychological formations. The review is an atypically clear application of the Freudo-Marxist core paradigm of the 1940s Frankfurt School for a more popular audience.

CANS in the Archive.

In the Max-Horkheimer-Archiv [MHA], there are four Bände, containers 696-699, reserved entirely for the materials generated during the ISR’s revision of CANS before it was submitted for review to the Rockefeller Foundation in late early March 1941.19 The material below is divided into three main parts: first, a transcription of the final version of the proposal dated February 24th, 1941;20 second, my own reconstructions, which involved both transcriptions of earlier English drafts and translations of the earliest German drafts, of two individual sections of the proposal: the “Introduction” to the proposal as a whole and Horkheimer’s thematic section on “Anti-Christianity” in particular.21 The third part is a reconstruction of the supplementary memorandum for CANS. The memorandum seems to have been written more than a month after the proposal was first submitted, and with the purpose of providing the reviewers a clearer picture of the materials the ISR would have access to, or collect, for the project and their methods—in particular the method for the interview process for other German refugees and the principles for creating a “Living Record.”

Method of Reconstruction.

Because there are more than 26 different drafts, in both English and German, of the same individual sections of CANS, I had to develop a unique approach in reconstruction to both avoid redundancy and highlight variation. Thus, in reconstructing the two earlier variants of the individual sections I selected—again, the “Introduction” and Horkheimer’s “Anti-christianity”—I adopted the following procedure.

Step 1: Choose one English draft of a given section of the ‘final’ version of the proposal (2/24/1941) both most complete in its form and most divergent in its content relative to its ‘finalized’ counterpart.

Step 2: Use the chosen English draft as a new point of departure for choosing one earlier German draft of the same section according to the same criteria (completeness-form; divergence-content).

This is particularly evident in the reconstruction of the “Introduction” below, which consists of a transcription of one, earlier English draft and a translation of one, earlier German draft of the section. For the reconstruction of the “Anti-Christianity” section, I found my own two-step model insufficient because of the greater variations between each of Horkheimer’s individual drafts—particularly the German drafts. Accordingly, I added another step:

Step 3: After completing steps 1 and 2, check the alternate versions of both the earlier English draft (chosen in Step 1) and the earlier German draft (chosen in Step 2), then create a ‘composite’ by integrating the most significant variations in form/content of the section from these alternates in both English and German.

This accounts for the fact that there are three variants of “Anti-Christianity” included below: the first, a composite transcription from two English drafts, both of which were titled “Nietzsche and the Struggle against Christianity”; the second, a translation of a German draft titled simply “Nietzsche”; the third, a composite translation of two versions of a German draft titled “Anti-Christianity and Nietzsche.”

Tasks for Future Reconstruction.

In the near future, I hope to finish the full reconstruction (or de-compromising) of CANS in the interest of recovering the more radical critique of liberal and social democracy that was all too obvious in the earlier drafts of each section: Adorno’s unique methodological reflections on the investigation of aesthetic productions as “unconscious historiography,”22 Löwenthal’s sociology of liberal Weimar press under the aspect of conflicts between industrial and financial-commercial capital,23 Neumann’s unsparing critique of the role of the reformist labor movement in facilitating the rise of fascism,24 and Marcuse’s references to the ambivalence of the young post-war generation that clung “unconsciously and quasi-neurotically, to the very things it attacked.”25 In any case, despite all of the limitations of the below reconstruction, I hope you will find something in it that will not be entirely boring!

—James/Crane (7/13/2025)

Contents.

I. Cultural Aspects of National Socialism (2/24/1941).

BUREAUCRACY — Pollock.

MASS CULTURE — Lowenthal.

ANTI-CHRISTIANITY — Horkheimer.

THE WAR AND POST-WAR GENERATION — Marcuse.

IDEOLOGICAL PERMEATION OF LABOR AND THE NEW MIDDLE CLASSES — Neumann.

LITERATURE, ART, AND MUSIC — Adorno.

II. Earlier Variants of Individual Sections.

A. “Introduction.”

“Introduction.” (English Draft)

“Introduction” (German Draft).

B. “Anti-Christianity.”

“Nietzsche and the Struggle against Christianity.” (English Draft)

“Nietzsche.” (German Draft 2)

“Anti-Christianity and Nietzsche.” (German Draft 1)

III. Memorandum to supplement the Research Project “Cultural Aspects of National Socialism.”

IV. Horkheimer—The Psychology of Nazidom [Review of: Brickner’s Is Germany Incurable?] (1943)26

I. Cultural Aspects of National Socialism (2/24/1941).

The research project on CULTURAL ASPECTS OF NATIONAL SOCIALISM is designed to fulfill a dual purpose: to contribute to the psychological attack against totalitarian Germany and to elucidate one problem for Europe’s post-war reconstruction, namely, the attitude of the German people towards their regime.

The breakdown of the imperial German system in 1918 was not so much the result of military and economic defeat as the consequence of the complete disruption of Germany’s national morale. A military defeat need not necessarily lead to revolution. Germany’s defeat resulted in a revolution because of the superiority of the Wilsonian theory of New Freedom, his fourteen points, and because of the passionate faith of the masses of the German people in the validity of the democratic doctrine. This much is recognized even by General Ludendorff in his war memoirs.

Today, two different trends appear in discussions of the attitude of the German people to National Socialism. While the one tries to drive a wedge between the National Socialist party and the people, the other believes every German to be in fact, or at least potentially, a National Socialist giving full backing to the regime’s imperialist aims. It is obvious that this problem is of decisive significance. The character of the psychological struggle against Germany must be determined by the answer to this problem. Scientifically designed propaganda within Germany can only be successful only if the degree of the permeation of the German people with the National Socialist ideology is ascertained. European reconstruction will be largely determined by whether the German people are inherently aggressive and imperialistic or whether they are merely tools in the hands of an aggressive minority.

Our project is centered around these problems. We hope to ascertain the real facts by an analysis of those cultural processes which led to National Socialism and the ideological ties that keep National Socialism together.

The problems are set out in the outline which is the joint work of Professor Eugene Anderson of the American University, Washington, D.C., and of the Institute of Social Research, affiliated with Columbia University.

A supplementary statement, available upon request, discusses the research method which the group intends to apply. This supplement devotes considerable attention to the utilization of the collective experience of those German refugees who played some role in Republican Germany and in the underground opposition to early National Socialist Germany. A provisional list of these refugees who are to be questioned is supplied. Finally the additional memorandum discusses the extent to which our proposed study differs from existing publications on National Socialism. For this purpose an extensive bibliography of English works is included.

Convinced that such a research project will be of value only if the needs of the U.S. are fully considered, the study group has set up for each section of the project advisory committees as follows:

Bureaucracy: Lindsay Rogers, Columbia University (Chairman); W. Richter, Chicago; Leon C. Marshall, American University, Washington, D.C.

Mass Culture: Robert M. MacIver, Columbia University (Chairman); Theodore Abel, Columbia University; Frank Mankiewicz, College of the City of New York.

Anti-Christianity: Reinhold Neibhur, Union Theological Seminary (Chairman); Paul Tillich, Union Theological Seminary; Adolf Keller, World Council of Churches, New York.

The War and Post-War Generation: Robert S. Lynd, Columbia University (Chairman); Robert Ulich, Harvard University; William H. Kilpatrick, Teachers College, Columbia U.

Ideological Permeation of Labor and the Middle Classes: Harold D. Lasswell, Washington D.C. (Chairman); Max Lerner, Williams College; Alfred Vagts, Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, N.J.

Literature, Art, and Music: John B. Whyte, Brooklyn College (Chairman); Mayer Schapiro, Columbia University; Ernst Krenek, Vassar College.

The members of the advisory committees have pledged themselves to cooperate actively in the formulation of the frame of reference of the questions to be put to the German refugees and in the final formulation of the results.

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

(The name in parentheses indicates the scholar directing the work for the section concerned. The entire group will assist in the preparation of each section.)

INTRODUCTION.

BUREAUCRACY — Frederick Pollock.

MASS CULTURE — Leo Lowenthal.

ANTI-CHRISTIANITY — Max Horkheimer.

THE WAR AND POST-WAR GENERATION — Herbert Marcuse.

IDEOLOGICAL PERMEATION OF LABOR AND THE NEW MIDDLE CLASSES — Franz Neumann.

LITERATURE, ART, AND MUSIC — Theodor W. Adorno.27

INTRODUCTION.

The project aims to provide an understanding of National Socialism by placing the movement in its cultural setting. It is guided by the interest to determine the forces that produce totalitarian society and hold it together. The time has arrived to analyze in all its aspects this menace to the value system of Western civilization and to do so with the different instruments science places in our hands. The economic problems of totalitarianism are covered by other studies now in progress, but the cultural problems have not yet been treated on the basis of an integrative method. They will form the subject matter of this project.

The studies proposed in this memorandum focus on typical problems and situations in order to elucidate basic processes. They do not aim to cover the whole field of National Socialist culture. The topics, however, have not been casually chosen, but have grown out of the intellectual interests and the actual experience which the scholars participating have acquired in their collaboration over a period of years. They will draw upon their combined knowledge of Germany and the cultural changes taking place throughout the world. The sketches that follow indicate some of the problems that will be dealt with in each section of the project.

Bureaucracy. The decisive problem is to determine where the seat of political power lies in contemporary Germany. An analysis of the origin, function, and social composition of the various types of National Socialist bureaucracy may enlighten us as to the relation between the party and the civil service and may help us to learn what conflicts can arise out of this relation.

Mass Culture. The uniformity of life under National Socialism contrasts sharply with the diversity and richness of individualistic culture. It is an urgent problem to determine and examine the factors that prepared public opinion for authoritarianism prior to its advent to political power. The non-political section of the daily press, the illustrated magazines, and the popular biographies may play a considerable role in transforming independent men into beings ready to surrender their individual rights, and in maintaining such a state among them.

Anti-Christianity. The anti-Christian activities of National Socialism go far beyond its anti-church policy and may be an expression of social currents that lay deep in the German nation. Why did the efforts to combat anti-Christian ideologies meet with failure? An investigation into the specific nature of German anti-Christian thought, its exponents and the groups supporting them, should help to solve this problem.

The War and Post-War Generation. “Youth in Distress” is a key group in every totalitarian movement. A considerable section of National Socialist leadership has been molded by the youth movement. What definite part did such factors as economic insecurity, the disintegration of the family, and educational shortcomings play in building the totalitarian mentality among the youth?

Ideological Permeation of Labor and the New Middle Classes. The strength of National Socialism depends largely upon the degree to which its philosophy has penetrated great masses of people. Precise conclusions as to the resistance of labor and the new middle classes to the Regime may be indicated by changes in the National Socialist slogans, the National Socialist manipulation of pre-Hitlerian doctrines, and the shifting direction of the terroristic apparatus.

Literature, Art, and Music. The intellectuals as a group play a major part in the rise of totalitarianism as well as in the struggle against it. Their ambivalent role in Germany will be inferred through an interpretation of their works. Art under totalitarianism, more than any other government-controlled activity, may yield a clue to the forces and tendencies prevalent among the population.

These problems are the more disquieting since they arose within the framework of a democracy, the very progressive constitution of which gave every opportunity to the people to obtain representation for their actual interests. It appears that the consciousness of the people had been modified to such an extent that they voted against their own rights, thus inducing collapse of all that democracy stands for. Since American democracy may not be entirely beyond this danger, though its foundations are incomparably deeper than Germany’s were, our project hopes to make a contribution to American interest. It will analyze the powers that threaten to pervert the consciousness of a democratic people into its opposite. Our approach is based on the conviction that what we have to face is not a fated, inescapable, and irrational “wave of the future,” but is rather something due to social factors open to scientific investigation.

The studies will be largely based on the rich material in the possession of the Institute of Social Research, some of which is not available elsewhere. It will be supplemented by interviews with German refugees from all walks of life. In view of the fact that the authoritarian governments are rapidly falsifying the picture of European culture and particularly in view of the German regime’s willful destruction of all kinds of documents, it appears the more timely to utilize material and information available in this country.

The members of the group recognize that objectivity will be difficult to preserve in these studies, but they feel that their experience in countries other than Germany should enable them to interpret on a comparative basis the course of events in Germany. They also believe that social science methodology has provided some means and developed some habits of control over one’s prejudices and assumptions.

Dr. Eugene N. Anderson has assumed the co-directorship of this project and has already collaborated in the preparation of this outline. He will, jointly with Dr. Horkheimer, supervise the work of the entire group and will continuously advise in shaping the material to the best uses of the American intellectual public. The Institute’s affiliation with Columbia University may afford an opportunity to draw in qualified students and to make them acquainted with the methods applied.

BUREAUCRACY.

Director: FREDERICK POLLOCK.

This study will discuss the character and significance of bureaucratism during the Weimar Democracy and under National Socialism. It will deal with all types of bureaucracy, governmental as well as industrial (including labor and party) and will to some extent contrast the role of bureaucratism in Germany with that in other Western countries.

I. The mere numerical extension of the public servants or salaried employees is not in itself enough to characterize a condition of bureaucratism. Therefore we shall endeavor to dissect the concept of bureaucratic rule into its constituent elements.

The relevance of distinctions in the method of appointment, promotion, dismissal, and pensioning for the creation of a bureaucratic type will constitute the first group of investigations. We shall attempt to compare American and German methods.

There must exist certain political constellations allowing us to speak of the rule of bureaucracy. Of special importance in this connection will be the waning of parliamentary legislative power and the decay of the influence which parliamentary committees have over the administration.

We shall try to determine whether the control of positions of political power by the bureaucracy is sufficient or whether such control has to be supplemented by that of certain positions of economic and social power.

Psychological considerations may play a considerable role. They may be operative in two directions. First, we must examine whether the German bureaucracy (in contrast e.g. to the American one) developed a caste spirit which marked it off from the public and, if so, what historical forces shaped it. Secondly, we shall try to determine the reaction of the public towards the bureaucracy. One of the many problems involved here will be the character and the extent of the security which the civil services enjoyed and the reaction it produced in the various strata of the people.

We shall have to work out a typology of the German bureaucracy. This typology will distinguish between the public, party, and the private bureaucracies, between the huge masses of the lower civil servants and the higher ones, between the managerial bureaucracy in the industrial organizations and big corporations and the labor bureaucracy within the parties and the trade unions, etc.

This typology will be utilized for an intensive study of the interaction between public, party, and private bureaucracies.

II. The growth of the bureaucracy, in numbers and functions, during the first world war, had begun to shift power to the bureaucrats and threatened to widen the gulf between the civil service and the public. The attempts of the Weimar Democracy to draw the state machinery closer to the people by devices supplementing the parliamentary system will be investigated under three categories:

Appointing non-careerists to the civil service. This was unusual in the Empire. The methods used and their success or failure will be set forth in special studies of the Prussian, the Thuringian and the Bavarian developments.

Extending the self-government of municipalities as well as of the administrative bodies handling economic and social matters, e.g., the social security administration. Success or failure of these attempts to establish the principles of a pluralistic collectivism within the parliamentary system will be studied in the developments of the respective agencies (arbitration boards, labor courts, etc.)

The growth in the function of private bureaucratization (cartels, trade associations, giant corporations, trade unions) will be studied through the following problems:

The economic sectors in which this process is most conspicuous;

The role played by the universal trend toward a split between ownership and control;

The methods of selection for the higher bureaucratic positions.

III. At the end of 1932 the political power of the ministerial and army bureaucracies had attained heights beyond any previously held. We propose to investigate the character and background of this development and the relation between it and the destruction of self-government, the decline of parliamentary supremacy in legislation, the decline of parliamentary control of administration, and of the budget right.

The attitude of the civil service toward parliamentary democracy will be investigated, with particular attention paid to the following problems:

The psychological effects of bureaucratic power;

The efforts of the Republic to imbue the bureaucracy with a democratic spirit and the methods it developed for selecting and training young civil servants;

The social composition of the bureaucracy.

The discussion will be used to clarify the question as to whether and in what degree the anti-democratic slogans met with the approval of the bureaucracy.

The role of the German teachers as civil servants will be compared with the political role of teachers in France and the U.S.A.

An analysis of the criticisms that the various political parties advanced against the bureaucracy will help to clarify the situation during the Weimar Republic.

IV. We shall analyze the changing attitude of National Socialism toward the civil service and its function and role, dividing the discussion into three periods:

In the first stage, up to June 1934, we shall deal with the rapid growth of the influence of the permanent bureaucracies upon National Socialism and its ideology, and with the economic and social reasons for this development, and with the relation between the party and the old bureaucracy. (The doctrine of the totalitarian state.)

In the second stage we shall analyze the complete break with the Prussian tradition which appears in the subordination of the state bureaucracy to that of the party. (The doctrine of the “movement’s state.”)

In the third stage we shall investigate the National Socialist theory concerning the relationship between the three originally competing bureaucracies (state, party, estates). Then we shall discuss the new type of bureaucratic leadership which seems in the process of making. This type is composed, it would appear, of the state bureaucracy, the party bureaucracy and the estates bureaucracies (industrial managers, cartel officers, etc.). We shall try to find out where the decisive social, political and economic discussions are reached, what the social composition of the newly emerging bureaucracy is, and what the principles and processes are for selecting, training and indoctrinating the younger generation.

MASS CULTURE.

Director: LEO LOWENTHAL.

This will be a study of the character of the mass culture prevalent in contemporary Germany and of the emergence of it out of the diversity of cultural types found in Germany before the World War. It will discuss how far attempts to prevent the formation of a mass culture succeeded or failed during the Weimar Republic and in what respect this culture provided a foundation for National Socialism. A study will be made of the patterns of mass thought and action by way of their manifestations in certain newspapers and popular biographies. One such pattern involving ideas of purity and corruption will be studied in detail. The manifestations will be related to the conditioning background of industrial capitalism and urbanism as basic factors in producing the mass culture, and to the defeat in the World War and the effects of the inflation, as additional factors especially significant for Germany.

The newspapers will be selected in such a way as to cover representative social groups in Germany. The contents of the papers will be analyzed in order to ask whether or not there emerged mass-patterns irrespective of party, class and interest. The impact of big industry upon newspaper policy, incident upon a change in ownership, will be studied in the case of the Frankfurter Zeitung, a characteristic democratic paper which claimed to safeguard individualism but which nonetheless had to make concessions to prevalent mass tendencies. The Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung, as the most popular illustrated weekly, and Vorwärts, the Social Democratic organ, are two others that will be used. The reciprocal influence of advertisers and reading public on the one hand and of newspaper policies in the selection of news items and the formulation of popular culture types on the other will particularly be investigated—for example, the enthusiasm for sport, the standardization of taste, modes and habits, the close resemblance between editorial and advertisement, text and picture. In this way light should be thrown on the question of whether the characteristics of man as revealed in totalitarian society were already ripe in the Weimar Republic. A study will be devoted to the National Socialist press (Völkischer Beobachter, Schwarzes Korps, Stürmer). We shall try to find out in how far this press was what it pretended to be: an opposition to the materialism of modern society, to the rule of money and internationalism, and in how far, per contra, it showed the features of the metropolitan press. It will be asked to which impulses and sentiments the National Socialist press appealed and through which mechanisms it attracted particularly certain backward groups of the German population. For this purpose we shall compare the National Socialist press with the anti-rationalistic, sectarian publications which it resembled in the beginnings, the gutter press, the astrology magazines, the natural cure periodicals.

The popular biographies will be analyzed for evidence of current social and cultural ideals. The extent to which their liberalistic ideal of personality expressed common traits with the totalitarian cult of the leader will be discussed, and the methods, style, structure of thought used by the authors will be analyzed in terms of the cultural setting. The social significance, for example, of the interest in great personalities, of the longing for guidance by some heroic figures, of the deep concern with emotional factors, will be brought out, and the direct and specific reaction of the public to these biographies will as far as possible be investigated.

Among the cultural patterns to be studied, those concerned with purity and corruption will be treated in particular. The keen and widespread interest in these two forms will be explained, and the significance of the change in the public attitude toward them will be shown. The forms will be dealt with as possible expressions of the incompatibility of social standards with the economic and political conditions of post-war German society. The political use of scandals, the practical bearing of the attitude toward purity and corruption in both public and private affairs upon the emergence of National Socialism (the relation to racialism, for example), and the peculiar fact that the National Socialists who protested against corruption during the Weimar Republic become themselves arch-corruptionists—all these problems will be discussed.

This study has its specific value for the whole project in the fact that it deals with the intermediary instruments for reflecting and shaping the standards of popular thought and conduct. Even though these instruments are expressions of more basic forces, the popular social forms conditioned by the basic forces are most clearly revealed in them.

ANTI-CHRISTIANITY.

Director: MAX HORKHEIMER.

This study undertakes to explain the anti-Christian trends of National Socialism in their historical as well as ideological significance. We shall try to determine whether or not the anti-Christian tendency of National Socialism reflects a far-reaching change in European culture. Special attention will be given to the relation between such cultural manifestations as industrialization, urbanization, and power politics, on the one hand, and the change in the social position of the Christian religion, on the other.

This section will deal with three main groups of problems.

The historical aspect will be brought to light through an analysis of the anti-Christian movements and activities that have flourished especially since Bismarck established the Reich by force. We shall try to determine and explain the inroads of anti-Christian sentiments among the various strata of the population. A sociological analysis of the role of the church during this period will supplement the discussion.

The ideological roots of the movement will be approached through an analysis of representative writings, such as those of Richard Wagner and particularly Friedrich Nietzsche. By comparing them with the aims voiced in the contemporary popular movements, we shall investigate in how far Nietzsche’s and Wagner’s attitudes made manifest ideas and sentiments that were prevalent among the population.

A study will be made of whether and to what extent the National Socialist system corresponds with Nietzsche’s ideas about replacing Christian morals with a new order of values, and whether and in what ways National Socialism attempts to transform religion according to its own power-purposes. We do not aim to give a survey of church politics under National Socialism, since this has been done expertly by others. We shall try instead to use certain ideas as a basis for a historical sociology of the Christian religion in an era of swift change in moral ideas and practices.

[Under 1]

As documents of the anti-Christian movements we shall scrutinize pamphlets, party programs, leaflets, etc., as well as discussions on this subject in the Reichstag and the different state diets, anti-Christian feeling in the right political wing, the revival of old pagan cults, the struggle against the Old Testament and the Catholic Church will be studied as revealed in the newspapers, speeches of anti-Christian leaders (Reventlov, Hauer), confessions of dissident pastors of this political shade. The expressions of left-wing anti-Christian trends will be analyzed in the anti-religious policy of the Socialist and Communist parties, as crystallized in the Socialist newspapers and theoretical writings of these parties, especially Die neue Zeit (since 1883). Monists and freethinkers figured in the general current and may yield important clues as to the social composition of the anti-Christian groups and influence of the natural sciences on their opinions. An analysis of the content of novels, such as Fontane’s and Raabe’s, may prove helpful to discover anti-Christian tendencies in certain other social groups, such as the army, the teachers, the bureaucracy, the lower middle classes.

[Under 2]

Wagner’s and particularly Nietzsche’s work will be used as outstanding examples of certain anti-Christian traits of the German mentality. Through the analysis of their philosophy we hope to establish the categories of anti-Christian thought which we shall check against those unconsciously prevalent in the present-day German mentality and even in that of certain sections of the population of other countries. Other anti-Christian ideologies that had an inner bearing upon German culture during the last decades (Houston Stewart Chamberlain, Oswald Spengler, Stefan George and his school, Moeller van den Bruck, Ludwig Klages, and Martin Heidegger) will be discussed in this connection. Works officially recognized by National Socialism (Alfred Rosenberg) as well as speeches of National Socialist leaders will be evaluated both linguistically and psychologically in order to determine in how far they are influenced by Nietzsche and to what extent Nietzsche’s ideas are really alive in National Socialist ideology, or whether they have been, either consciously or unconsciously, distorted in it. By showing the relation between Wagner and Nietzsche on the one hand and the currents of popular thought and action on the other, we hope to contribute to an understanding of the social role of the intellectual in modern life.

[Under 3]

We shall investigate the way in which National Socialism tries to mold the religious feelings of the population to its own needs, by an analysis of the schoolbooks, ministerial decrees, teachings in the army, governmental policies concerning the family, and other related media. As a basis for this analysis we shall use the discussions inside the churches during the Weimar Republic and under National Socialism, in particular the material showing the positive and negative influence that the world war and the inflation had on the church and on religious thought in Germany. The doctrines of protestant religious leaders (Karl Barth and Friedrich Gogarten) and of the promoters of a Catholic Renaissance (Guardini, Przywara, Scheler) and their influence will be studied. The general problem here is to determine whether and in what respect efforts to renovate religious education and to restore the original impulses of Christianity eventually facilitated the acceptance of a new authoritarian scheme. We shall use not only printed and unprinted material but shall also interview German theologians who have taken an outstanding part in German religious life and who are now living in this country. We shall supplement our study of protestant and Catholic religious theories with regard to anti-Christian trends in Germany by a cultural and psychological study of those representative religious leaders who succumbed to the National Socialist doctrine and of those who opposed it.

THE WAR AND POST-WAR GENERATION.

Director: HERBERT MARCUSE.

The problem of this section will be to examine the German youth as a decisive agency through which the fundamental political, social and economic experiences of the war and post-war years transformed the prevalent ways and philosophies of life. The main object of this discussion will be the effect of war, economic crisis and unemployment on the family, and on the ideals and attitudes of the young generation. It is our intention to analyze these changes in order to discover in how far they contributed to the disintegration of democratic and to the promotion of authoritarian ideas among the young generation.

This study will be based primarily on the following material:

The programs and official publications of the German youth movement.

The reports on the meetings of the youth congresses.

Interviews with representative figures of the German youth movement and of German progressive education who are now in this country, some of whom will be used as experts for this section.

The biographies and memoirs of some leaders of the war and post-war generation supplemented by fictional material of documentary and reportage value.

The reports on some characteristic trials of German youths (see below under III).

The Institute possesses a valuable collection of material pertinent to this study (questionnaires, manuscripts written by experts and participants, published literature).

The German youth experienced the breakdown of the Imperial system as the change from a relatively stable and evenly progressing culture to one of extreme insecurity. The reaction of this youth to such phenomena as inflation and technological unemployment will be studied through an analysis of the activities and ideas of the youth organizations. Special attention will be given to the question as to what agencies focused and transmitted the growing anti-democratic tendencies, and to the part played by those literary and philosophical currents which had been undermining the standards of liberalism ever since the turn of the century (Nietzsche, Burckhardt, Dostoyevsky, George).

We propose three special studies:

The youth movement proper.

The so-called Front Generation and the Free Corps.

“Youth in Distress”—an attempt to discover types of juvenile delinquents and asocials that are of social and political significance in the transition to National Socialism.

1. The Youth Movement Proper.

The unusual phenomenon that will first have to be explained is the politicization of the German youth. The situations and agencies will be studied which made the German youth a political youth to such an extent that it regarded all existential conditions and problems immediately as political questions. We shall see in how far this attitude transformed the traditional patterns of life and hampered all endeavors to establish a unified democratic culture.

The structure, organization, and activity of the youth movement has to be examined with a view to determining in how far they reflect the conflicts that came with the social and economic liquidation of the first World War. Special attention will be given to the activity and ideas of the hiking clubs, “Wandervogel”, so-called, (which had tremendous appeal for the emancipated types of German youth) and the experimental country private schools. The thoughts and acts of representative personalities like Gustav Wyneken and Hans Blueher will be analyzed.

We shall discuss the struggle between liberal and authoritarian tendencies in the activity and literature of the youth movement. Special stress will be laid upon the role played by the youth “leader”. Moreover, it will be shown to what extent even the democratic and non-partisan youth movement fostered the ideals of strength, obedience, and collectivism and thus adumbrated the fascist ideology.

The discussion within the youth movement seems to indicate family conflicts and conflicts in adjustment such as Freud designated as causing dislocations between the individual and his environment. The methods and concepts of modern psychology, particularly of psychoanalysis, will be used as a clue to understanding the psychological make-up of the German youth.

These three studies will be supplemented by a comparative analysis of the youth movement in France and England in order to find out in how far the German youth movement represented a specific type of the war and post-war generation and in how far it shows features common to the French and English youth movement as well.

2. The Front Generation and the Free Corps.

The situation of the so-called front generation provides an appropriate ground for a study of the cultural changes involved in the transition from war to peace. We propose to attack the problem through a study of the right radical free corps, the organization of young war veterans. It will be asked how German democracy approached the task of leading those young people who had learned the habit of violence in the World War back to a life and culture of peace-time and transforming their war-time habits of violence into productive activity.

We shall investigate in how far this task was complicated by the economic crisis which prevented any permanent adjustment and drove these groups to band together in private armies and semi-military organizations of their own.

The study on the front generation will be centered around a series of case studies of the life of representative leaders among the front generation. Such case studies may be justified by the fact that the free corps later contributed a large part of the National Socialist leader personnel; this connection, therefore, might elucidate the psychological set-up of those strata which influenced the transition from democracy to National Socialism. We suggest also a study of the terrorist methods of the German right radical organizations, which may yield excellent parallels for an understanding of the source and character of National Socialist terror.

3. Youthful Delinquents and Asocial Types.

In this section, we intend to study certain types of juvenile delinquents and asocials in order to investigate the connection between a permanently unemployed youth and social and political extremism. The question will be discussed as to whether this quantitatively small number of cases offers insight into the rapidly progressing radicalization of the German youth in the post-war period. This study of youthful delinquents and asocials may illustrate a method we intend to apply throughout our project, namely, to select certain extreme cases and situations that aroused public opinion in Germany during the transition from democracy to authoritarianism, and to analyze these cases in such a way that they throw light upon the social and psychological make-up of the German population (cf. the problem of corruption in our section on mass culture).

The typology of delinquents and asocials will have to be established as a preliminary to looking for decisive traits common to these and the National Socialist terrorists. Homosexuality may be an important factor in this connection. The study will be documented with the memoirs of Roehm, Salomon, Schlichter, Strasser, and such. The Institute will also utilize the material which it collected on the psychological attitude of certain groups of German unemployed.

THE IDEOLOGICAL PERMEATION OF LABOR AND THE NEW MIDDLE CLASSES.

Director: FRANZ NEUMANN.

This study will be developed around the problem of how far the National Socialist philosophy has penetrated among the German masses and to what degree that philosophy actually corresponds to certain longings among a definite strata of the German people. We shall attempt to infer the real attitude of the masses (I) from an investigation of whether the National Socialists have made any fundamental changes in their ideology, (II) from the relationship of the constituent elements of the ideology to doctrines formerly prevalent in Germany, (III) especially from the doctrine of the new imperialism as it relates to previous trends, and (IV) from the relationship between the principles of National Socialist social organization and those formerly prevalent in Germany. This indirect method seems mandatory for a cultural approach to National Socialism, because, in contrast to democratic societies, the [former’s] policy of synchronizing the whole life of the people does not allow of directly ascertaining the real feelings and sentiments of the masses.

I. We shall first examine the social function of official National Socialist political philosophy, contrasting it with the way public opinion is formed in democratic societies. This will permit us to determine the relation of National Socialist philosophy to the socio-political reality. We shall thus analyze typical slogans of National Socialism in the different stages of its growth, with a view to determining to what social strata they appeal. The slogans cited below will be used as clues to the nature of the regime’s appeal to certain institutions and groups.

We shall discuss only in passing the slogans that held sway prior to the conquest of power (i.e., “breaking the fetters of interest”), and shall concentrate on those changes that occurred during the regime. Only a few slogans, such as that of the “Totalitarian state”, which were current during the first stage of the National Socialist rule, were later abandoned. The others were continued but with characteristic shifts of emphasis to take in different strata of the population. We shall investigate the shifts with a view to the various groups they were intended to influence, somewhat as follows:

Totalitarian state – civil service, army industry.

“Movement’s” state – the party, especially the brown-shirts and elite guards.

Leadership state – middle classes, army, civil services.

Race superiority (anti-Semitism, blood and soil) – farmers, middle classes, free professions.

Proletarian racism against plutocratic democracies – workers.

The catch-word of anti-bolshevism merits special attention. We shall investigate in how far certain groups (i.e., the army and industry) took it seriously from the very beginning, and whether it was changed in recent years for other reasons than those of foreign policy.

The material for this analysis will be collected from the reports of the party congresses and those of their affiliated organizations, official periodicals and newspapers, as well as from the legislative enactments and decisions of the law courts, disciplinary courts, and courts of honor. The material collected by the anti-National Socialist refugee organizations will supplement the above documents.

II. The study of the ideological appeals made by National Socialism to the different social groups will be supplemented by an analysis of the state of mind of those masses, as this was shaped in the Weimar Republic. We shall restrict this examination to the workers and the new middle classes. Special attention will be given the question of what attitudes towards authority prevailed among their political and social organizations and found their way into their philosophies.

Nationalism and Militarism: The nationalist unions of salaried employees (white collar); the agrarian unions (Landbund); company unions; “peaceful” unions; the Stahlhelm;

Nationalism and Militarism: The nationalist unions of salaried employees (white collar); the agrarian unions (Landbund); company unions; “peaceful” unions; the Stahlhelm;

Catholic Solidarism: The Center party; the Catholic unions; their leisure organizations;

Progressive Liberalism: The Democratic party; the salaried employees unions;

Reformist Marxism: The Social Democratic party; The Free Trade Unions, consumers cooperatives; sport and other leisure organizations; the republican militia (Reichsbanner); labor welfare organizations;

Syndicalism: The Allgemeine Freie Arbeiter-union; heretic groups within the labor movement;

Revolutionary Marxism: The Communist party; the Red Trade Union Opposition, the Red Front Fighting League, the Red Help.

This analysis will be focused on two problems, (a) that of the development of submissive traits; (b) that of the affinity between the ideology of groups named above and the ideology of National Socialism.

(a) The roots of the peculiar amenability to authoritarian control that characterizes the masses in totalitarian Germany will be traced through analysis of the social and psychological status of labor and of the new middle classes ever since the Empire. We shall attempt to determine the types of obedience and submissiveness as these were manifested among the two groups and at different periods:

The Untergangengeist of the imperial period and the problem of whether (and how) the behavior patterns of the army hierarchy found their way into civil life (the role of the non-commissioned officer and of the reserve officer).

The influence of party discipline and of an organizational bureaucracy on forming the character structure of German labor. Special attention will be given to the relation between proletarian emphasis on “solidarity” and organizational discipline.

The relation of the National Socialist pattern of leader-follower to the two previous types.

(b) The transformation by National Socialism of symbols, slogans, and doctrines mentioned above will be studied in light of whether National Socialism did not fulfill cravings that were already operative within the Communist, Social Democratic, Catholic and Democratic labor movement. We shall examine whether the incorporation of the old Marxist slogans into the National Socialist philosophy conceals or expresses an identity of contents:

Classless Society – People’s Community

The proletariat as the bearer of truth – The supremacy of the Germanic race

Socialism – The common welfare preceded selfish interest

Class Struggle – The war of a proletarian race against plutocratic democracies

The material for this section is contained in biographical and autobiographical materials (Erzberger, Bernstein, Bebel, Ebert, Noske, Scheidemann, H. Mueller, Otto Braun, Grzesinsky, Sender, Radek, Muenzenberg, Thaelmann, Valtin); in proletarian novels, in the periodicals issued by political groups (Neue Zeit, Gesellschaft), in parliamentary debates, in the polemic literature against the rule of the “Bonzen” (bosses). We shall also make use of an inquiry which the Institute of Social Research, then in Frankfurt on Main, conducted in 1932, as a means of determining the specific character traits of German workers and salaried employees. For the last stage of the Weimar Republic, the returns in parliamentary and Works Councils elections will be of special value. The latter statistics have never before been utilized. Interviews with refugee leaders will be introduced.

III. The studies outlined above prepare the ground for an evaluation of the decisive stage of National Socialist ideology, namely, that which accompanies the present war. We wish to answer the question which strata the policy of “racial-social imperialism” relies on. The historic role of the following groups will be studied in their contribution to shaping the doctrine of the new imperialism:

The agrarian sector — Eastward expansion, naval policy.

The industrial sector — Westward colonial, Asiatic and South American expansion. The problem of “hatred of England.” Army and naval expansion.

Middle class liberalism — The pan-German union; colonies; naval expansion; the dream of a Grossdeutsches Reich.

The working classes — “Social imperialism” within the social democratic party and the trade unions, (Lensch, Schippel, Winnig, Renner) (Material see under II).

IV. The understanding of the appeals of National Socialism to the various strata will be facilitated by comparing the National Socialist principles of social organization with those of the Weimar Republic. We shall find out to which social strata the following categories of National Socialist organization are applied, how far a terroristic machinery is used to carry them out, and against whom it is primarily directed.

(a) The principle of mass atomization. We shall deal with the problem of how National Socialist collectivism actually entails the complete dissolution of all occupational and personal solidarity of interests, especially among youth and labor.

(b) The principle of “divide and rule.” We shall ask whether the slogan of a “people’s community” does not allow of a privileged treatment of small groups within each social stratum, especially among the peasantry, old middle classes, and labor.

(c) The principle of elite selection. We shall attempt to explain how the continual spread of National Socialist organizations over all strata of the population coincides with the selection of small but reliable elites within them. For example,

The general SS — The “troops on call” (Verfuegungstruppen) and the “death’s head formations.”

The general Hitler youth — the stem (Stamm), Hitler youth.

The German Labor Front — The National Socialist troops in the plant (Werkscharen).

Study of these principles may provide a key for determining how far National Socialism relies on consent and repression.

The material is to be found in the legislative enactments, decisions and administrative rulings, in the statistical material, especially on labor relations, the publications of the Labor Front, the police, the party, the women’s organizations, the estate organizations, the decisions of the Erbhofgerichte.

The labor institutions and the wage policy of the regime have been studied for the past seven years by the Institute. In addition, studies have been published or are about to be published which can be used for our purpose here.

LITERATURE, ART, AND MUSIC.

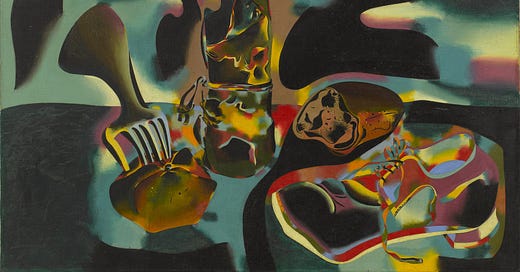

Director: THEODORE W. ADORNO.