Translation: Letters After Munich 1918/19.

Horkheimer's correspondence with Germaine Krull & Katja Walch-Lux. (+ Notes)

Contents.

Notes on Munich (1918-1919) and After (1920-1968).

Letter to Maidon: On Will and the Terror (July 14th, 1920).

Correspondence with (and about) Germaine Krull (1922).

Correspondence with Katja Walch-Lux (1934-1937).

Correspondence with Katja Walch-Lux (1967-1968).

The spoils which fall to the fascist belong to him by right: he is the legitimate son and heir of liberalism. The wealthiest estates have nothing to reproach him with. Even the most extreme horrors of today have their origins not in 1933, but in 1919, in the shooting of workers and intellectuals by the feudal accomplices of the first republic. The socialist governments were essentially powerless; instead of advancing down to the very basis of these events, they preferred to remain on the loose topsoil of the facts. In secret, they held the theory to be a quirk. The government made freedom a matter of political philosophy instead of political practice. Even those who may privately have every reason to do so should not wish humanity to repeat this. It would run the very same course as the original.

—Horkheimer, ”The Philosophy of Absolute Concentration” (1938).

Notes on Munich (1918-1919) and After (1920-1968).

My research on Max Horkheimer’s intellectual development has taken me back to his political education in revolutionary Munich (1918-1919), when he first became an avowed communist. Below, I’ve translated letters from exchanges Horkheimer later has with two of his closest friends from that period: the modernist dancer Katja Lux (1897-?), later Walch-Lux, and the pioneering avant-garde photographer Germaine Krull (1897-1985). The core of these exchanges, to paraphrase a formulation Horkheimer uses elsewhere, is the struggle never to side against the unfulfilled dreams of youth with the baseness of the same reality that made them unfulfillable, not even when the dream recoils into despair. Because these translations are part of a larger research project on the political context and consciousness of early critical theory, the following notes should be considered sketches for a future essay on the political education of Max Horkheimer, in conjunction with “Research Notes: Horkheimer’s Marx/ism Studies (1919-1927).”

Note 1: Katja Walch-Lux (1934-1937).

Due to the significance of Krull’s unpublished autobiographies as documents and reflections on the transformation of radical intellectual culture between left-wing political associations and avant-garde artistic movements in late Wilhelmine and early Weimar Germany, more recent biographies of Horkheimer (Abromeit, 2011 [2004]) and Pollock (Lenhard, 2024 [2019]) have focused on Krull’s role in their formative experience of revolutionary Munich, remarking in passing that Lux first formally introduced Horkheimer and Pollock to Krull and, by extension, the broader social circles and cultural milieu of the left-opposition to the German Social Democratic Party (hereafter: SPD) in bohemian Munich.1 To date, I’ve been able to find out very little about Walch-Lux outside of the contents of the letters below and the editorial notes that accompany them in Horkheimer’s Gesammelte Schriften. From the letters alone, however, it is clear that Walch-Lux was not only an eccentric and troubled friend of Horkheimer and Pollock’s, but an original author and thinker in her own right. By 1934, she had become part of Wilhelm Reich’s inner circle in Copenhagen, studied analysis with them, and worked on the 1934 issues of their Zeitschrift für Politische Psychologie und Sexualökonomie (ZPPS). She also worked with Reich directly, conducting research and preparing the manuscript for his analysis of character-formation in the USSR, “Der Kampf um das ‘neue Leben’ in der Sowjetunion” (1936). This text was published in Part 2 of his book Die Sexualität im Kulturkampf (1936), later editions of which were published under the title The Sexual Revolution following Theodore P. Wolfe’s English translation for Orgone Institute Press (1945).

In her 1934-35 letters to Horkheimer and Pollock, Walch-Lux, then going by the name “Ingrid Griegot,” writes about being torn between her total devotion to ‘the movement’ (she and her husband, Viktor (Vitjà) Kunze, still belonged to the KPD in exile) and her total devotion to her career as a dancer and dance instructor—whenever she’s immersed entirely in ‘the movement,’ she can’t help but wonder what it’s for if not to make creative life possible; whenever she’s intensively training herself and others in dance lessons, she can’t help but wonder if it’s all a waste of time while the world burns. Her reflections on this tension are the reverse side of her judgment of Reich, whose over-identification with the revolutionary cause makes it impossible for him to distinguish between his scientific and political work; this, in turn, makes him incapable of either, triggering the dissolution of the Copenhagen ‘Reichists’ and his expulsion from both the International Psychoanalytic Association (hereafter: IPA) and the communist party:

Reich is a very dangerous man—for he is no politician, which even he now admits, but his evening discussions were thoroughly politicized + on a totally false basis—after his expulsion from the Communist Party, he would become slightly aggressive at everything the Central Committee (ZK) would say—Due to his excessive inner attachment to the party, he began to transfer all of his hatred onto it—because of his terrible wound—

—Katja Walch-Lux to Max Horkheimer and Friedrich Pollock, 12/5-6/34.

Walch-Lux’s characterological reflections on the painful separation and identification with the revolutionary ideal are occasioned by Horkheimer’s response to her initial letter in August 1934, their first contact in many years, in which Horkheimer writes how happy he was to discover that Walch-Lux hadn’t begun to wither away, to grow old and spiteful in inverse proportion to the greatness of their unfulfilled ideals:

You are entirely right, fundamentally people change very little, and as I write this letter I imagine us speaking to one another just like we once did. More precisely: upstanding people change little; the majority, however, start out with grand ideals and begin to wither away, growing old and spiteful. Your letter shows you are nothing of the sort! And, as far as I can judge, that’s not the case with Fritz, Maidon, or myself either. “We try to do our best.”

—Horkheimer to Katja Walch-Lux, 9/26/34.

According to Horkheimer and Pollock, this is precisely what happens to Germaine Krull in 1922.

Note 2: Germaine Krull (1922).

After the defeat of the Munich Soviet Republic, Krull is expelled from Bavaria in late 1919. She travels to the USSR with her fiancé, Mila (Samuel) Levit, another refugee from the violent state-sanctioned repression of the left-opposition, in the hopes of joining the kind of revolutionary struggle that had become impossible in Germany.2 In the USSR, Krull is arrested on charges of engaging in counterrevolutionary activity due to her increasingly vocal opposition to and agitation against the Bolshevik government for the sake of the Free French cause against Lenin.3 During her incarceration, Krull suffers serious bouts of recurring illness, both physiological and psychological, and is accordingly rotated between the harsh treatment she receives during her internment in hospitals, which only aggravates her condition, and confinement in a solitary prison cell. The 1922 correspondence with and about Krull begins with her letter to Horkheimer and Pollock from Stettin hospital following her release and expulsion from Russia. As if anticipating rejection, Krull immediately declares herself an anti-Bolshevik. While Horkheimer and Pollock help coordinate her passage through Bavaria with her mother and provide financial support for her recovery, they reject her anti-Bolshevism on principle. In an aphorism from Dämmerung titled “Indications,” Horkheimer argues that in 1930, there is one question which serves as an infallible index of the moral character of a person: their attitude towards Russia, towards “the continuing painful attempt to overcome” what Horkheimer calls the “terrible” and “senseless injustice of the imperialist world.”4 In a way, this judgment is already contained in Horkheimer and Pollock’s co-authored reply to Krull’s initial letter and especially in Horkheimer’s letter to Maidon about Krull having tragically, prematurely, grown so old:

… How horrific suffering must be to make one so old. … I would rather surrender my life than let us grow old. To be young is: to be obsessed with love— … ; to be old means: to lose faith in what is human and become “hard”—to no longer have any goals (i.e., to do the worse!), as is clear from her letter. …

Horkheimer to Rosa Riekher, 1/23/22.

For Horkheimer, Pollock, and Maidon, the episode with Krull validates and intensifies their shared conviction that fidelity to the revolution through its defeat and betrayal demands an egoism suspended between the extremes of “making ourselves human for others” and “self-love.”5 In shared affirmation of the seemingly paradoxical stance of protecting themselves from the bitter disappointment of the anti-Bolshevik by rejecting any idealization of the Bolshevik party program, or that of any other extant communist party, they would safeguard the revolutionary promise between each according to ability and each according to need.

Note 3: Horkheimer (August 1917—October 1918).

Despite Horkheimer’s early and uncompromising hatred of the World War, Abromeit (2004) argues that Horkheimer’s position prior to late 1918 would best be characterized as ‘non-political’ (or: unpolitisch).6 To construct the problem as a juxtaposition:

In August 1917, Horkheimer wrote: “Challenged by the literature of the socialists, I sought my own weapons, my own politics, but I did not find anything that could have been called similar, even in form, to any of the programs existing then.”7 According to Abromeit, Horkheimer’s generalized contempt for mass politics of any kind was complicated by a fundamental conflict of conviction which increasingly became the explicit focus of Horkheimer’s literary experiments between 1914 and 1918: on the one hand, Horkheimer’s highest moral value was the aesthetic education of the individual, which could only truly occur in the aesthetic spheres of culture beyond politics; on the other, Horkheimer was certain that anyone who refused to compromise their moral and aesthetic ideals would necessarily incur their own ruin as a result of the structure of modern society. To the extent Horkheimer could have been said to have ‘political’ views before fall 1918, Abromeit (and Horkheimer himself, in a later interview) describes them in reactive terms—as an opposition to the celebratory jingoism of the conservatives, the resigned ‘realism’ of the liberal bourgeoisie, and the SPD’s support for the war effort despite its pretense to be an opposition party.8 Horkheimer was drafted into military service in 1916. After a brief stint as a medical aid in Southern Germany, his already poor health worsened and, while his unit was stationed in Munich in the spring of 1918, he was judged unfit for further service by a doctor and committed to the Neu-Wittelsbach sanatorium in Munich for nearly all of the remainder of the war.9

By October 1918, Horkheimer would be an outspoken partisan of the revolutionary program of the Spartacists.10 During his first excursions outside the walls of the sanatorium into the city of Munich in 1918, Horkheimer met and befriended Katja Lux, who formally introduced him to Germaine Krull shortly thereafter. Krull’s studio was a hub for the left-opposition in Munich, and had ties to some of the most important figures in the Bavarian Revolution (November 1918) and the short-lived Munich Soviet Republic (April-May 1919).11 This included including Kurt Eisner (1867-1919)—former journalist and theater critic, then head of the Independent Social Democratic Party (hereafter: USPD)—and Ernst Toller (1893-1939)—close friend of Walch-Lux, expressionist author and playwright, successor to Eisner at the head of the USPD after the latter’s assassination on February 21st, and key player in the political dramas in which the executive council of the Munich Soviet Republic would be embroiled throughout its brief rule.12 As Krull later recalled in an unpublished memoir of her time in Munich, Horkheimer quickly made a name for himself as a sharp and outspoken supporter of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht in heated discussions with Toller: “Max was in his element. The discussions were always very interesting and [Ernst] Toller was not always the most convincing. Max was a supporter of Rosa Luxemburg and [Karl] Liebknecht; Toller defended either [Kurt] Eisner or himself.”13

Note 4: Munich (1918-1919).

… The streets were filled with workers, armed and unarmed, who marched by in detachments or stood reading the proclamations. Lories loaded with armed workers raced through the town, often greeted with jubilant cheers.

The bourgeoisie had disappeared completely; the trams were not running. All cars had been confiscated and were being used exclusively for official purposes. Thus every car that whirled past became a symbol, reminding people of the great changes.

Aeroplanes appeared over the town and thousands of leaflets fluttered through the air in which the Hoffmann government pictured the horrors of Bolshevik rule and praised the democratic government who would bring peace, order and bread.

In the evening all leaders assembled in a huge hall of the Wittelsbach Palace, the seat of the new government. Hard work with almost permanent committee sessions lay ahead. Suddenly somebody started singing the Internationale. The others followed and the Royal Palace resounded with the ecstatic voices of a bizarre crowd choking with emotion, much closer in appearance to a dedicated church congregation than to tough Communists.

I cried and some of the ‘ruthless blood-thirsty criminals’ were struggling to suppress their own tears. …

Rosa Leviné-Meyer on the beginning of the ‘second phase’ of the Munich Soviet Republic, 4/13/1919.14

Accounts of Horkheimer’s activities between the outbreak of the revolution in November 1918 and the fall of the Munich Soviet Republic in May 1919 are surprisingly vague.

Abromeit’s reconstruction of this period consists of two claims: first, that Horkheimer “clearly sympathized to some extent with the council republic” but “maintained a safe distance from the turbulent political events”; second, that Horkheimer “identified with the lofty artistic and intellectual ideals which animated the first phase of the council republic” but “felt that the conditions were not yet ripe for radical social change.”15

The first claim can be justified as a loose restatement of the fact that Horkheimer spent the winter studying for the Abitur exam to qualify for university, which he and Pollock pass in the spring. But Abromeit goes further, claiming “the next few months [viz., after October, 1918] would prove that Horkheimer was unwilling to translate his radical theoretical convictions directly into praxis.”16 Abromeit’s ‘proof’ seems to run in two directions: the absence of any evidence of political activities between November 1918 and May 1919 (through the November Revolution, Spartacist uprising, and Munich Soviet Republic) is itself taken as evidence for a practice-avoidant character structure, which is then invoked as the causal factor which explains the lack of evidence from which it was first inferred. The second claim does not match the facts of Abromeit’s own account. First, according to Krull’s autobiography, as well as Abromeit’s description, Horkheimer first articulated his own socialist politics as a partisan of the Spartacist program of Luxemburg and Liebknecht in explicit opposition to Ernst Toller and Kurt Eisner’s understanding of the USPD platform. This alone suggests Horkheimer would be much more sympathetic to the ‘second phase’ (4/13-27) of the Munich Soviet Republic under the direction of Eugen Leviné (1883-1919) and the other communists. In fact, it is during this second phase that Horkheimer writes Maidon:

And if this letter is lost in the fighting soon to come, and neither telephone nor dispatch brings news to you, know this—please, my love, know this: I love you boundlessly, my longing for you is indescribable, only a short time still separates you from me (how endless it seems!), then you will be with me—You: have faith, repose, and assurance in this! Do not trust the lies about Munich. The liars want to murder—to murder for money; there is neither madness nor injustice here: When you are with me once more, there is so much I want to tell you, never to be restless again. I know that you love me as no one else can, and I will always carry you with me—up—or—down. You—my love!17

Second, not only does Abromeit exclusively provide evidence that Pollock is the one who expresses the belief that conditions were not yet ripe for revolution, but even if Horkheimer did share such reservations, this was itself a political position—namely, the policy of the KPD under the direction of Leviné in opposition to Eisner first, then Toller.18 Third, there are very strong reasons to doubt Horkheimer would have shared such reservations. Horkheimer writes a letter to Maidon at the end of February about that month’s issue of Die Aktion memorializing Liebknecht and Luxemburg, asking her to “please read from beginning to end, without skipping a single line; it provides a basic outline of our political intuitions.”19 The issue opens with a six-stanza poem by Franz Pfemfert titled “IMMORTAL!” [“UNSTERBLICHE!”], a rallying cry for the workers to form up in the spirit of Luxemburg and Liebknecht to prepare for the fast-approaching “final battle” [“Endkampf”] and finish the fight they left us “today.” The first two articles are Luxemburg’s ”Order Prevails in Berlin” (1/14/1919) and Liebknecht’s ”In Spite of Everything!” (1/15/1919), the last texts either would author. The former ends with as direct a critique of the dismissal of revolution on the basis that ‘conditions are not yet ripe’:

The question of why each defeat occurred must be answered. Did it occur because the forward-storming combative energy of the masses collided with the barrier of unripe historical conditions, or was it that indecision, vacillation, and internal frailty crippled the revolutionary impulse itself? … Both! The crisis had a dual nature. The contradiction between the powerful, decisive, aggressive offensive of the Berlin masses on the one hand and the indecisive, half-hearted vacillation of the Berlin leadership on the other is the mark of this latest episode. The leadership failed. But a new leadership can and must be created by the masses and from the masses. The masses are the crucial factor. They are the rock on which the ultimate victory of the revolution will be built. The masses were up to the challenge, and out of this “defeat” they have forged a link in the chain of historic defeats, which is the pride and strength of international socialism. That is why future victories will spring from this “defeat.”

“Order prevails in Berlin!” You foolish lackeys! Your “order” is built on sand. Tomorrow the revolution will “rise up again, clashing its weapons,” and to your horror it will proclaim with trumpets blazing:

I was, I am, I shall be!

The latter ends with an apocalyptic prophecy of the Day of Redemption, the Day of Judgment, drawing near:

The Road to Calvary of the German working class is not yet completed—but their Day of Redemption is near. The Day of Judgement for the Ebert–Scheidemann–Noske and for the capitalist rulers, who still to this day hide behind them. The tide of events mount into the heavens—we are accustomed to being catapulted down from the peak into the depths. But our ship continues on its straight course proudly sailing to its goal.

And whether we will still be alive when it is reached—our programme will live; it will rule the world of humanity redeemed. In spite of everything!

Under the roar of the approaching economic crash the still sleeping hordes of proletarians will awaken as if summoned by the trumpets of the Last Judgement, and the corpses of the murdered fighters will rise and demand a reckoning from the damned. Today, still the subterranean rumbling of the volcano—will erupt tomorrow and bury them all in glowing ash and lava flows.

If we take the claim seriously that these articles contain the basic outline of his political intuitions as of February 1919, Abromeit’s portrait of Horkheimer from November 1918 through May 1919 is, at the very least, incomplete. Lenhard (2024) provides an important twofold clarification: (1) while Pollock later claims “he and Horkheimer considered the subsequent Soviet Republic a ‘calamity’ from the outset,” Krull’s memoirs specify that Pollock in particular reacted to the declaration of the Soviet Republic (“[t]his proclamation is completely idiotic; one should arrest Toller immediately…”)20 by making a variation of the social democratic argument “that the time was not yet ripe for a communist revolution”; (2) as intimated by Abromeit’s account, Horkheimer and Pollock were spurred into action not by the revolution but the reaction: “While the two friends played no role in the short-lived Soviet Republic, they did feel an urgent desire ‘to salvage what might be salvaged’ once it had been quashed. This was the wellspring of their first foray into something resembling active political engagement.”21 This brings us to the ‘White Terror.’

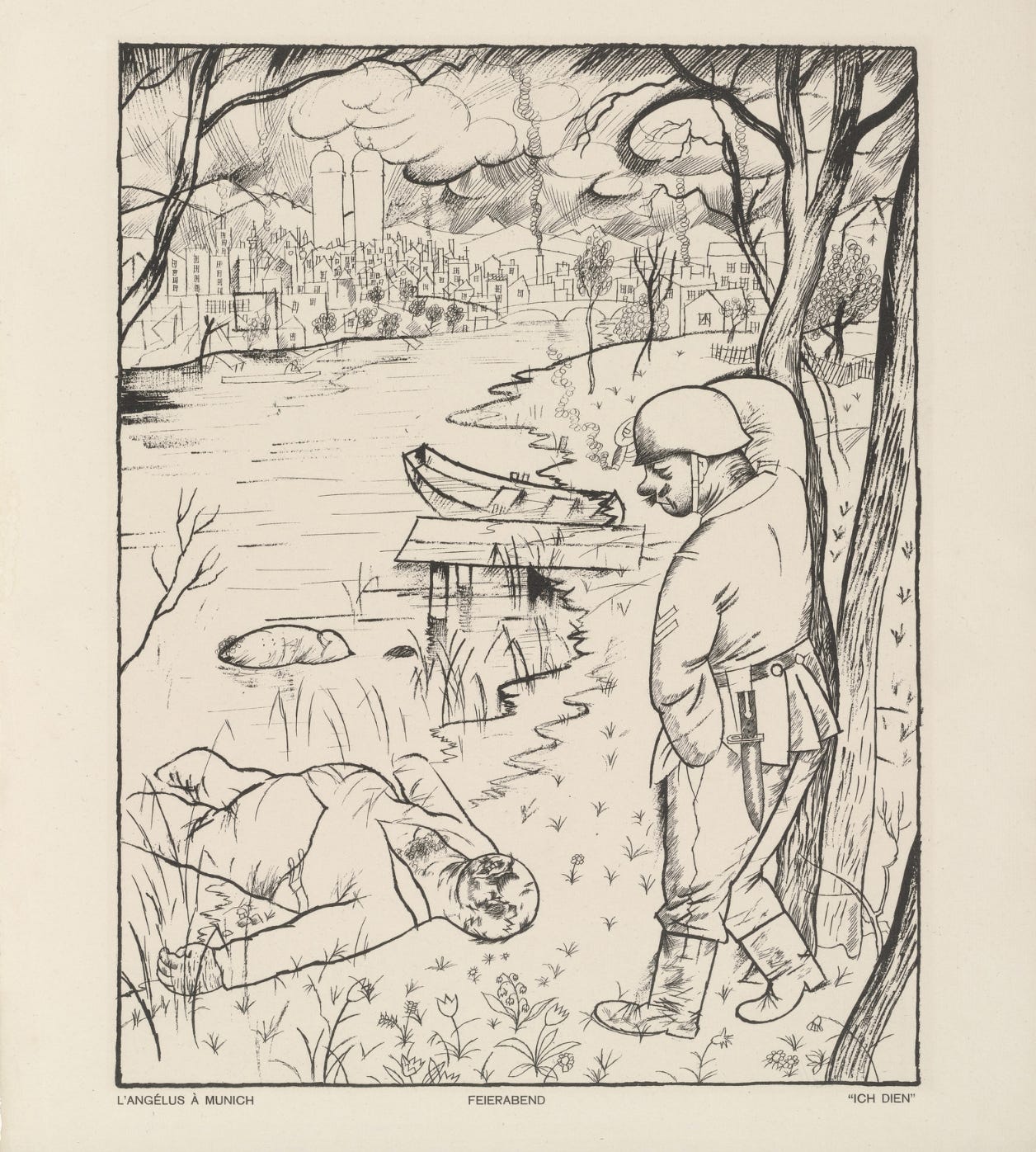

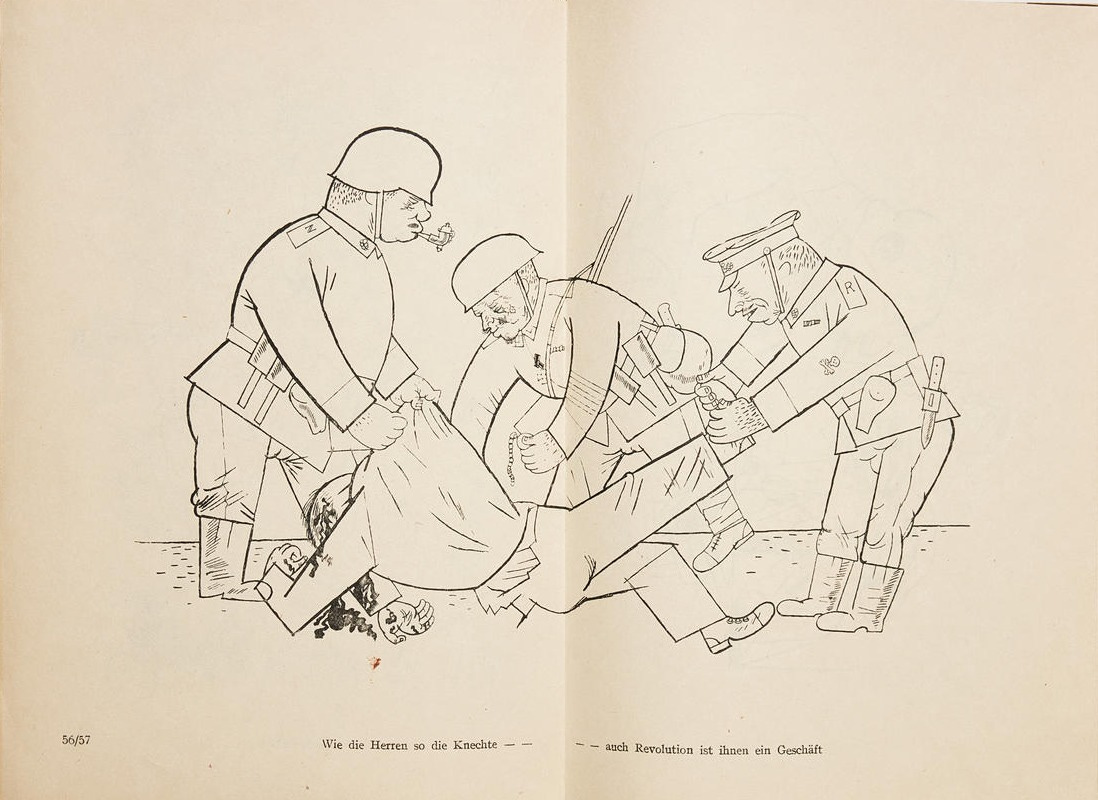

Note 5: The White Terror: May 1919—July 1920.

Krull watches the white troops enter the city with Horkheimer and Pollock from the balcony of their apartment. In the early days of the ‘White Terror’ in Munich, “[m]ore than 600 actual or alleged communists were literally hunted down and murdered in the streets, thousands were arrested and tortured.”22 Recalling the arrival of the White Army, Krull writes:

From the window of Max and Fritz’s flat we saw the red flags burning. Then they were replaced by the blue-and-white Bavarian flag. They were patrolling the streets, everywhere there were arrested workers with their hands tied behind their heads. The Whites were determined to find the ringleaders responsible for Toller’s folly—at any price. Having failed to detect even one, they decided to go district by district, beginning with the working-class quarters. None of the leaders were found. A sense of fear and torment prevailed. I stayed with Max and Fritz since they lived in a distinctly bourgeois area where it was less dangerous than it would have been in my studio in Schwabing.23

During the white terror, Horkheimer and Pollock would work with Krull to use their apartment, resources, and connections to shelter and facilitate the escape of participants in the Munich Soviet Republic now on the run from military, paramilitary, and police forces. Horkheimer and Pollock sheltered Tobias Axelrod (or: Akselrod) (1887-1938), a Russian emissary, political journalist, and one of the three communists with a seat in the central council of the republic during it’s ‘second’ phase. After Axelrod escaped Munich with Krull and another partisan (Willy Budich), they were arrested while crossing the Austrian border and handed over to German authorities.24 Krull was the only one released. On the return trip to fetch Krull from the border, Horkheimer was detained and interrogated by Freikorps paramilitary units twice, both times because he was mistaken for Ernst Toller, who had since gone into hiding.25 Shortly thereafter, “one of their acquaintances was killed in a shootout in Odeon Square” and they offered refuge to another fugitive, Elia Pupko, a philosophy student in Munich and close associate of Eugene Leviné.26

While Pollock helped set up a committee to provide material and legal support for political prisoners, Horkheimer traveled Germany with Krull in the summer of 1919—at one point seeking support from Franz Pfemfert, editor of Die Aktion, though unsuccessfully—in an effort to free Axelrod from prison before he met the same fate as Gustav Landauer (1870-1919) and Eugene Leviné.27 Landauer, anarchist-socialist author and romantic mystic with close ties to Martin Buber,28 briefly served as commissioner in the first phase of the Räterepublik. He was arrested by counterrevolutionary forces on May 1st, 1919 after they broke through the Munich defenses. He was murdered on May 2nd, en route to Stadelheim Prison, by officers of the Freikorps under military orders. According to one eyewitness account, his last words to the soldiers surrounding him were: “I’ve not betrayed you. You don’t know yourselves how terribly you’ve been betrayed.”29 Eugen Leviné—along with Axelrod and Max Levien (1885-1937), the head of the Bavarian KPD—led the communist faction in power for the second phase of the Soviet Republic. Leviné was captured on May 13th and tried in early June. On June 3rd, the court sentenced Leviné to death, accusing him of being a “foreign interloper in Bavaria,”30 and the sentence was carried out on June 5th. Leviné was shot to death by a firing squad at Stadelheim Prison. In his last address before the court, Leviné brings his speech to a close with the famous lines:

We Communists are all dead men on leave. Of this I am fully aware. I do not know if you will extend my leave or whether I shall have to join Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. In any case I await your verdict with composure and inner serenity. For I know that, whatever your verdict, events cannot be stopped.31

Though Krull and Horkheimer failed to find influential support for Axelrod in Germany, he would be released in early 1920, despite having been sentenced to 15 years in prison, after his lawyers successfully argued for his diplomatic status as a member of the Russian press. Axelrod would return to Russia, and (like Levien, who had been living in exile in Russia since 1921) would be executed in the great purges of 1937/38 as Stalin’s faction consolidated power.

In late summer 1919, Krull was preparing for her ill-fated pilgrimage to Russia with Mila (Samuel) Levit, another refugee from the violent state-sanctioned repression of the left-opposition, in the hopes of joining the kind of revolutionary struggle that had become impossible in Bavaria.32 Krull recalls Horkheimer’s grim assessment of the situation in Munich, shortly before they parted ways, on the problem of continuing the revolution in times of reaction:

There are two types of revolution, not just one type. … There was a revolution in the streets, and it was inspiring, but the streets now mean death. All the great leaders are dead—Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht, Kurt Eisner etc. The reaction is strong now, associated with the socialist government. The reaction is always well-organized, because it has money and weapons. The second way of making revolution consists in entering into the government and sabotaging it. This type of revolution is not bad and can in the long run be better. Karl Marx says, when the revolution in the streets is over, it is necessary to enter into the government and sabotage it. Thus there are two methods, but conflicts can also arise, because some might say that the revolution in the streets is over, and others might say that it is still alive. … I am afraid that Lenin, as a good Marxist, realizes that the revolution in the streets is over.33

In a later journal entry (Entry No. 5 [9/19/1925]), Horkheimer writes: “one must be wary of making prognoses about the possessor of certain basic principles solely on the basis you know something of some of the principles they possess,” since there is “something much more central than those basic principles: namely, […] the kind of person they are.” To the extent that Horkheimer still retained the same principles he possessed before winter-spring 1918/1919, the person who possessed them had changed fundamentally. Lenhard (2024) writes:

This unrelenting succession of dramatic events forced the two friends to abandon what remained of their inward-looking adolescent mindset. Their support for the persecuted revolutionaries was motivated by a new-found political consciousness born of the upheaval in Munich. To be sure, they had previously adopted Schopenhauer’s normative concept of compassion and were in thrall to the principle of human solidarity, but only now did society come into focus as a category worthy of examination in its own right. Their turn to the social sciences, in the widest sense of the word, followed directly from their novel experiences in Munich.34

Horkheimer’s letter to Maidon of July 14th, 1920 is a remarkable example of this reconfiguration of Schopenhauerian principles according to the demands of a new political consciousness of revolution and reaction. The letter is a reflection on the philosophical ramifications of the ongoing terror in Hungary and Germany for conceptualizing the antitheses of reason and will, law and love, objectivity and passion, etc. The occasional cause of the letter is news of the Fehér Terror (white terror) in Hungary (1919-1920/21), during which mobile battalions of counter-revolutionary forces inflicted mass anti-communist and anti-Semitic violence on real or suspected partisans of the defeated Hungarian Soviet Republic (March-August 1919), and of the ongoing Spa Conference (July 5th-16th, 1920), where representatives of the Weimar Republic renegotiated terms of disarmament and war reparations after the Reichswehr’s brutal suppression of the Ruhr uprising through mass, summary executions of real or suspected partisans of the revolutionary workers’ councils (March 13th-April 6th, 1920). It is also, however, a love letter, and not just to Maidon: Nietzsche’s love of the Übermenschen of the future is interpreted as the distortion of compassion for human beings in the present, scornful towards the modern world that first scorned it.

The letter concludes with a curious pair of reading recommendations for Maidon: long selections from Schopenhauer’s most substantial works—World as Will and Representation (1818), Two Fundamental Problems of Ethics (1841), Parerga and Paralipomena (1851)—alongside Nikolai Bukharin’s Programme of the World Revolution (1918). Having been convinced by Pollock to read Bukharin’s Programme together in August 1919, Lenhard (2024) notes that Horkheimer was “greatly impressed,” that both he and Pollock were “enthralled with the radicality of Bukharin’s demands”; Lenhard quotes the following from Bukharin’s ‘Preface’ to the Hungarian edition, which had been translated into the German: “Rather than fight for “democracy” … we proclaim the class dictatorship of the proletariat. Rather than engage in piecemeal reform, we turn the entire capitalist economic order on its head.”35 For Horkheimer and Pollock, the theory and science of society would have to be at least as comprehensive as the entire capitalist economic and social order the revolution would have to overturn. The final section of Bukharin’s Programme calls for an explicit demarcation of communists (here synonymous with: Bolsheviks) from social democrats given the schism that had already opened within German social democracy between the ‘extreme right-wing’ tendency, represented Philipp Scheidemann of the SPD, and ‘extreme left-wing’ tendency, represented by Karl Liebknecht of the “German Bolsheviks.” In words that cannot failed to have galvanized the young Horkheimer, Bukharin’s conclusion approaches a prophetic pitch as he predicts from the spring of 1918, when the Programme was first delivered, that the boundary line between the social democrats and the communists would soon be marked by blood.36 It is in this context—the immediate aftermath of the crushing defeat of the revolutionary experiments in the creation of Soviet Republics in Hungary, Bavaria, and the Ruhr—that Horkheimer radicalizes Schopenhauer’s metaphysics of the will into a critique of the supposed rationality of the new international world order, negotiated by the social-democratic government of the Weimar Republic and erected on the graves of the champions for a truly rational social order, liberators of the men who killed them.37

Letter to Maidon: On Will and the Terror (July 14th, 1920).

[Horkheimer to Rosa Riekher (Maidon), 7/14/1920.]38

Every day, I want to write you. But you know better than any that, for me, words—my words—are always too poor. For as long as I can recall, I’ve had to work hard for any sentence I meant to be true, and my manner of expression has seldom if ever been free of phony kitsch. If only I was able to reflect! Unclear concepts, half-remembered fragments of false knowledge, vainly absorbed Unkultur bar me insight into the simplest of connections. That this era lacks capacity for the creation of culture is our fate; we have found no attitude towards the world which would be our lot to deepen, contentedly develop; before us we see only disintegration, tearing-down, and decision-making struggles—long before the advent of a new community, but with all bridges behind us burned. My curse, however, is that I possess as parting gift from epochs past nothing but instinctive longing, will, and debts!—yet no language!

With such weak forces at my disposal (I measure myself not by strangers, but the wretchedness of my own nature), I seek to bring structure to the crude contours of my image of the world. Contemporary philosophy, together with insight into its immediate prehistory, is to serve as my map. I work as best I can, yet every evening I am ashamed of myself—comparison with others must be dispensed with, and stronger motives are needed if I am to free myself from this. On occasional evenings, two students come to us who’ve asked me for an introduction to questions of a philosophical and artistic nature. Fritz [viz., Friedrich Pollock] listens in as well, and often I talk for several hours at a time. To me, these occasions are tests of the clarity I’ve gained on the themes we discuss. Whenever these two young people walk away with a shine in their eyes, I experience a small, proud joy—for you—for then have I accomplished something.

Every week, I discuss the foundations of morality in a small group with Professor C. [viz., Hans Cornelius]. On this subject, we stand far apart. I owe him indescribably much, but this is precisely why I compromise nothing out of courtesy. I have discovered that no one knows what is important, and still I struggle to express this myself. More than two years past, May 1918, I sought to capture that which is essential (the Tagebuchblatt in your hands): every action between human beings harbors a contradiction.39 Is it truly “more blessed” to give or to receive? If I actively elevate serving love into law, what follows next from this but wounds, poverty, suffering; no help would then be of any benefit, and love would only repay its like with worse. Others would be advised to wean themselves off of life. But since everyone always has time for this, nothing can be foreshortened; because none can or should spare any part of this, since eternity stands at the ready and reduction of quantity of torment can only be bought by the worsening of its quality—preaching itself remains meaningless: if, however, the bloom of a life remains purpose, then the consequence is: “Thus I want man and woman: the one fit for war, the other fit to give birth…”40 and “But eating and drinking well, O my brothers, is verily no vain art.”41 Then our truth: “O blessed remote time when a people would say to itself, ‘I want to be master—over peoples.’“42 And then we must strip Nietzsche of his love for the Übermenschen, for the future; for what else does such hope signify but compassion warped into that which is distant? —The alternative is unavoidable if thoughtlessness will not help us overcome it. It is here that investigations must begin; it is here that we must create clarity, find norms, or be humbled, remain content with more honest skepticism. Does moral action find support in reason, or are intent and consequence rent by insoluble contradiction? No formal deduction from arbitrarily defined concepts may touch this terrible antithesis, nor contribute to its overcoming, but only a more ingenious grasp of actuality. —Of this I will speak to you long and often.

In praxis, this passion of compassion, love—but hate as well (from a second point of view)—rules over values. Only in study rooms does one imagine “reason,” not will, decides over good and bad; only professors fail to recognize that reason is a slave to will. Do we remain “objective” in the face of facts? Are we—“rational” before the news from Hungary,43 “matter of fact” before the haggling of the murderers in Spa,44 who, following their mutual acquittal, barter away the inheritance of the bereaved? They confer in white castles while prisoners are being castrated, boiling oil is being poured into women’s genitalia, and talk amongst themselves about poor finances. They live off homicide, plunder, slander—these representatives of all human vice—and conspire against a better future. They have yet to be sated from the incomprehensible horrors of the past and their present, and already we hear battle cries from them again: “the goods we hold sacred, justice, order, civilization, a place in the sun, the need to defend ourselves!” with which, as the horsemen of the apocalypse, they would sweep across the surface of the earth. —Can we just sit as calm, rational spectators in a glass house until they smash our windows in? Will we make the skeptical shrug of the villains and nine-times-wise the symbol of our existence? —No, we live and in our best hours our senses fail us! Then we race—blind towards the goal, and are wholly ourselves, without stolen thoughts or vanity.

It is not only on rare days, but ever since my love for you has robbed me of my senses, that I am so liberated. I can think more things over more fervently and live with harder suffering than most. Nevertheless, I have lost my senses; I feel as one who has signed over his soul, who toils hard in the face of manifold fate, suffers and rejoices, and knows that every path leads him to the same goal. For there you stand at the end of each of my thoughts—as my undeserved, boundless happiness. No passion has ever possessed a life so uncontested as love for you has mine. My work seeks you; my joy and my terror are yours. Though I may have been but a beggar before your immeasurable gift, I am Lord of all exalted realms since you love me. Because each step I take leads to you, I love my step and forgive myself, for you take me, as I am yours.

—Max

Separately, I’m sending you: Bukharin’s Programme, which you must read.45

Also read:

Schopenhauer II. Band, Welt als Wille und Vorstellung

1. Buch, Kapitel 17. Über das metaphysische Bedürfnis des Menschen

2. Buch, Kapitel 19. Vom Primat des Willens im Selbstbewußtsein

3. Buch, Kapitel 41. Über den Tod und sein Verhältnis zur Unzerstörbarkeit unseres Wesens an sich

4. Buch, Kapitel 46. Von der Nichtigkeit und dem Leiden des Lebens

Die beiden Grundprobleme der Ethik

I. Über die Freiheit des menschlichen Willens [Über die Freiheit des Willens]

II. Über das Fundament der Moral

(read in full!)

Parerga und Paralipomena II. Band

Kapitel IX. Nachträge zur Lehre v. d. Nichtigkeit des Daseins

Kapitel XII. Nachträge zur Lehre vom Leiden der Welt

Kapitel XIII. Vom Selbstmord [Über den Selbstmord]

Kapitel XV. Über Religion

Kapitel XXIV. Über Lesen und Bücher

(To your letter, which I have just received, I know only what I’ve already written above.)

(Leaf through Heine and also (though I don’t know whether you have it) through Kleist. Read much and report back how you like it.)

Correspondence with Germaine Krull (1922).

Germaine Krull to Max Horkheimer and Friedrich Pollock, 1/12/1922.46

My dear, dear people!

Be not amazed that I am still alive—exactly one year ago I crossed the Russian border once more, and—please, let me remain your friend—I am an outspoken anti-Bolshevik. After Mila’s departure,47 I was not permitted to leave the country by the Cheka;48 on October, 19th I was arrested yet again for being a spy and counterrevolutionary. I spent the next eleven and a half weeks in the hospital—that is, in prison—under horrific conditions, though I only had two hemorrhages, aside from all the nervous disorders. With great difficulty and hardship, I managed to escape with my life; I was expelled from Russia. Though I was not officially accompanied by a soldier, I was unofficially kept under strictest surveillance by spies—and this in the land of “freedom,” the land where workers rule. You know that I am honest; you can imagine it was no personal pettiness that made me the bitterest enemy of such people. Today I know that it would be a misfortune for the world, and above all for the working class, if Bolshevism were to come West. —I know history goes on and can only go forward, but this bloody experiment is an outgrowth of history—made into a crime by a few criminal masterminds. Forgive me, don’t be angry with me. I write how I feel, and you have a right to know even at the risk you can no longer call me your friend. I have realized that I gave up two years of my life for an ideal—great and noble—but still just an ideal. The ideal, realized in the hands of vain, vengeful, ingenious, but sick human beings has shattered an idea, has transformed the ideal into a crime.

And I will not stand for any crime. I say—have the courage to say—that I was wrong, and that I still have the courage to fight against it. Believe me when I say that I have suffered, that I write you this will all my heart and soul, I have suffered more in my damp solitary cell than I ever imagined I could—and I am losing my whole artificially constructed worldview, and with it my faith in everything good, in everything human, in all higher goals. —I have become hard, and feel as if I have recovered from a long sickness. I will work, I will look back upon my two hard years in the school of life with horror, but also with joy. With Mila—that was also a mistake. —With the people of the party and with Mila, I still have a score to settle. I believe you knew the slanders about me were only lies, —today I say openly, I stand on the other side. Remain my friends or not, you are the only I still regard as friends at all, and who I would be sorry to lose. Max, be the old friend. I [...] you in [...] 12 days en route—coming straightaway to Riga, [...]49 and in just a few days I will be in Germany. —I will telegraph you. I must speak with you. I will not even see Mila, though I bear his name—. I am sick. Try everything you can to make it possible for me to reenter Bavaria,50 I must see Mutti and rest and write my book. I hope we see one another soon.

From the heart—Your—Z.51

Horkheimer to Rosa Riekher (Maidon), 1/23/22.52

Maidon,

Here I am sending you Zottel’s letter, which just arrived today, in addition to the telegram from Stettin that arrived later. —It is hardly necessary that I tell you anything about my impression: there are surely fundamental grounds for opposing the social revolution on principle, which I can respect; however, this letter reeks, as if moldy, with “durch Erfahrung klug werden,” which—even if through the experience of physical death!—I have always hated. —I am curious to see the terrible changes it has had on such a person (in the end she might only be hatching from her egg!). How horrific suffering must be to make one so old. Maidon, I love you, time and time again I would rather surrender my life than let us grow old. To be young is: to be obsessed with love—with any love; to be old means: to lose faith in what is human and become “hard”—to no longer have any goals (i.e., to do the worse!), as is clear from her letter. I love you, through you I believe in what is human (even were humanity but beasts), through you I have the greatest of goals, and the happiest among all humans.

You—my happiness!

Max.

Max Horkheimer and Friedrich Pollock to Germaine Krull, 1/24/22.53

Zottel! All is well, for you are no longer separated from us by so many borders, behind such thick walls, behind a wall of villainy, so far away from all of the help that might reach you. We will speak with one another, and it must become a time of rest and clarity for you, a time in which you prepare a life for yourself whose meaning can no longer depend upon those factors over which you can have no control—upon neither the character nor the fate of any other human being, nor on circumstance, but solely upon your will and your reason. Your suffering (and how you must have suffered!) must not have been in vain; it is not enough that something change within you—something must begin! —First, however, you must rest.

The first signs of life we had of you after such a terrible pause, through which we knew nothing other than that you were in mortal danger and all on your own, was your telegram from Stettin which reached us on Saturday. What arrived was so garbled the address was impossible for us to decipher—which was compounded by the fact you had forgotten to mention you were in the city hospital. Since we did not know how you felt about Mila (your letter from Riga didn’t arrive until Sunday), we telegraphed him in Berlin that we suspected (really only guessed) you were in Stettin City Hospital. It was only in your letter of the 21st, which we received today, Tuesday evening, that we received clear details on your situation and address. We telegraphed immediately, and hopefully you will receive the telegram by the time this letter reaches you. When we sent the telegram, we wired your current address to your mother [viz., Albertine Krull], since we assumed that she, like us, had only received the address in your earlier communications in garbled form.

The question is now: what needs to be done immediately? We received notice that your mother obtained permission for entry through Count Pestalozza several weeks ago.54 If this really is true, then you will surely have already been given this news by your mother. In this case, it would be best if you went to see her as soon as possible and, at the very least, spent the first phase of your recovery in her care. —If this is not true, then there are two possibilities: either one of us comes to you, or you travel here to Frankfurt yourself, as soon as possible, so we can speak further. We consider the second possibility the more correct of the two; for, if one disregards the facts, freut sich immer nur der Teufel und seine Freunde. However, the facts are the following: traveling from here to Stettin and then back again, on top of a one to two day stay there, would cost us just enough that we—for want of cash—would be in no situation to do anything for your health and living situation there. We would only be able to speak very briefly, and then most likely grow frustrated that we started things off so clumsily. The first possibility on the other hand seems to have the following advantages: we could at the very least send you enough money for you to recover your health enough for the journey, and you would then be able to spend a few days here, during which time we could certainly hope for more than we could from an all-too-quick trip to and from Stettin. —If you can master your nerves for now—at least until we can speak—wird sich der Teufel nicht freuen. In any case: you are in Germany, and we know where you are. If you have not lost the last of what remains of your faith in what is human, then trust that we three human beings will hold onto our friendship with you until you have turned against us or what we hold sacred. There have been times when you no longer shared an understanding with us. We have good reason today to hope you have an insight into the meaning of our lives and the goals we serve. They cannot be found in any party-program, just as politics can never have the last word.

We await your reply. Since we don’t know anything about the conditions there, it would be best if you were to write or telegraph first, as we have indicated above, [X] Post Office, Frankfurt am Main. Please send us a direct address and where you would like us to send the money. Is there any danger that it might not reach you where you are, or that the hospital might confiscate some of it to cover costs, or something of that nature? See you soon!

Horkheimer to Rosa Riekher (Maidon), 1/25/22.55

Maidon,

Enclosed is the letter from Frau G. and Zottel’s second letter, along with our answer. It is our duty to be good to them, these people betrayed by all—however much we may differ in orientation. We must not—for the sake of our own beliefs—break our oath to support them. However I have the suspicion that she herself will very soon release us from this oath by her actions. Should we speak with her, we must be very clear, above all that the whole world must come second to our task. —Maidon, Maidon, in all lives, in all worlds, I would not give up the inexpressible bliss of possessing you! You illuminate my every step; you are everything woman can be for me: light in the darkness of this world. I love you. Max. Should Zottel come, you can be here too, if you are not above it! But whenever you come, I will not complain regardless!

—But I will kiss you!

Correspondence with Katja Walch-Lux (1934-1937)

Katja Walch-Lux (Ingrid Griegot) to Max Horkheimer, 8/22/34.56

My dear, dear Hork—when I read your name,57 I was overjoyed—I know for certain you will still know who “Schnackelberg” is, as Fritz always used to call me58—How long ago all of this was—and yet how near it has become through all the events of the last year

For some months, I’ve had to live here, ripped from my profession, my Bewegungsschule, my dance work—all dead, all buried. We are people of today, and so always in flight—one lives their life so infinitely quick—new people keep appearing—one is lost again—but everyone reappears somewhere—again after so many years—not, most times, having become strangers to us—but walking the same path as us—for it could not be otherwise. Since I’ve known the both of you, you and Fritz, ever since you saved me from my enthusiastic nonsense—that was 1919—I have continued on in exactly the same way.

Here it was mostly horrible—damned to inactivity, foreign language, without money, but after a short time one has already made old friends—and the work began once again—courses in sexual politics. The people will not be unknown to you—surely you know our issues of the Zeitschrift für politische Psychologie und Sexualökonomie59—so you have some idea of the circles I move in—my friend and husband has been here for a month now60—at first, we wanted to continue on to Finland—but now he is employed at the Russian Trade Association, since he is Russian himself—and everything has been easier for me—I myself am doing preparatory work for a psychoanalyst, W[ilhelm] Reich,61 for a book about Russia62—all this only in broad strokes—Hork, write me, are you together with Fritz?—[if] so

My warmest to you both,

Katja,

who currently goes by Ingrid Griegot.

Horkheimer to Katja Walch-Lux, 9/26/34.63

Dear Katja,

Yes—it was naturally a big surprise to receive your letter from Copenhagen! We have often wondered to ourselves where you ended up and how you are getting on. From the letter, it seems you are doing well, and we are glad. You will surely have grown impatient that my reply is coming so late. As you no doubt see from the stamp, however, I am far from Geneva at the moment, as is Fritz naturally, but we will be back—when, precisely, we cannot be certain—in the coming months. We are here because there is quite a bit of interest in our work in this country, and we have begun conducting some research in connection with several other institutions.

Will you be staying in Copenhagen for a while still? I do not know the city myself, but I’ve heard that it’s beautiful. I was in Stockholm only two years ago visiting a dear friend. You are entirely right, fundamentally people change very little, and as I write this letter I imagine us speaking to one another just like we once did. More precisely: upstanding people change little; the majority, however, start out with grand ideals and begin to wither away, growing old and spiteful. Your letter shows you are nothing of the sort! And, as far as I can judge, that’s not the case with Fritz, Maidon, or myself either. “We try to do our best.”64

Since we’re still quite unsteady here, it would be best for you to write the Geneva address; everything will be forwarded on to us from there. Please give Dr. Reich my kindest regards, and my warmest to you!

Katja Walch-Lux to Max Horkheimer and Friedrich Pollock, 12/5-6/34.65

Dear Hork and dear Fritz—no, truly—you’ve answered, that was so lovely, and I was so happy. It was a whole lifetime ago—Munich!—and what of today—things move forward with giant steps, events rush by one after the other—Tempo—Tempo—But we emigrants here have an unrest in us—a month of this goes by—even two—but then you feel the walls come up everywhere, condemned to inactivity again—Certainly you can still read, work, discuss—But what you’ve read has true value only if you can implement it practically—Denmark is a splendid country, if you’ve come here to relax, if you have money, if you’re a well-fed Bürger—But if you want nothing more with peace and quiet, if you wanted to practically get to work, then the most beautiful city can be yours—

I have been here since May—in July, my husband arrived—At first, we were supposed to go on to Finland, as he was supposed to work at the Russian Trade Association there. That came to nothing—we waited, then finally a position at the local Trade Association opened up. (That’s over now.) So here we sit chewing dry bread—in a lovely, sunny apartment we must vacate by the end of December for very obvious reasons—In my life, it has always been up + down, you know me! But in a foreign land it’s even worse—the emigrant aid organization which helped me get by until July has closed, no way back—where to at the end of December—probably a room somewhere with a comrade through Rote Hilfe,66 another place to eat—perhaps + my husband too [?]—But we’ve nearly gotten over the habit of thinking about it for any length of time—Vitja is actually a mathematician, but he’s never been able to [...],67 not take his Staatsexamen—why?—Here, I’m at a dance school, taking free lessons so I don’t start to rust, and in return I give lessons in dance + gymnastics according to my own method—(as an equivalent)—People here haven’t lived anything, haven’t undergone anything; you feel like you’re stepping back in time 15 years—They eat good “Smørebrote,” that’s the main thing—money has nothing to do with it—the “Kongen” is a social democrat—and the social-democratic prime minister Stauning,68 a monarchist! —That’s the truth!—He’s a guest of the “Kongen” [viz., King] + his best friend—here too, we’re sliding slowly but surely into fascism—and why not, everything must be tried out first! When have the Social Democrats ever learned anything! —The Communist Party is still young (only 4 years old)—but very capable—but with few members—though many sympathize with it—this is an unhealthy situation—Skilled workers earn a good wage, a bricklayer makes 50-60 Kroner a week, sometimes more—a tram conductor who’s served 8 years or more gets 400 Kroner. Life is proportionally expensive here—but the worker can buy + pay—Speak to a tradesman about it, they beam with pride: we are a very free country, for we have a social-democratic government; but most aren’t even in a party, have no interest in politics, they have it too good! —But those in the communist party, as opposed to the German communists, are much more active, much more interested, much better trained, that is, the average class-conscious proletarian—

When I arrived, I met some people from the Reich group by chance; I was in a poor psychic state, and so much of what the Reichists had to say fell on fertile soil in me—unfortunately, I have to say, because his Massenpsychologie aside, Reich is a very dangerous man—for he is no politician, which even he now admits, but his evening discussions were thoroughly politicized + on a totally false basis—after his expulsion from the Communist Party,69 he would become slightly aggressive at everything the Central Committee (ZK) would say—Due to his excessive inner attachment to the party, he began to transfer all of his hatred onto it—because of his terrible wound—When German comrades arrived who were still working illegally over there, he fell upon them in such a way (mocking their “loyalty to the party line” [Linientreue] and so on), that it was enough to make one stand up + say that’s not how it is—he became unobjective, knew nothing of what was going on in the world—his final dictum was: “a catastrophe is here; save yourself who can.” —Now he sits, the Katastrophenpolitiker, in Oslo—Now I’ve learned from an impeccable source that Reich has a “paranoia,” which has already progressed considerably; this explains a lot—his unspeakable manner of discussing and his expulsion from the International Psychoanalytic Association last summer.70 —He suspects nothing of this himself + I ask you not to spread this around either. —I’ve been in his company a lot in the past few months + this has made much clearer to me. —When Vitja, my husband, first arrived, we had a very hard time at first, as I was completely under the spell of the Reichists, for they also taught me quite a lot in their psychology courses. —But politically, unfortunately, I’d also been totally ruined, so that I often found myself inwardly in direct opposition to the party—Now, the Reich people have really dissolved into “nothing,” namely on account of his impossible behavior; only a very few remain who have any connection to him through analysis—The pamphlet he authored on his own, “Was ist Klassenbewußtsein,”71 is really very dreadful—Certainly, there are some good passages in it, but even these must first be unearthed + he must actually write an explanation of what he meant by them, since he neglected to formulate any of it clearly. Do you know his Charakteranalyse?72 Now he’s taken a totally new approach—and it’s such a shame that such a gifted man has plunged overboard into politics in his own field + has made himself impossible—now, he’s just a sick man who must be isolated, because he is in fact that far gone. As for me myself, torn—career and politics—I chose my career myself, after so many detours I became dancer + teacher—had a large school for many years—teaching made me happy—And then in a fever of activity, torn away from it head over heels + had to give it all up, certainly, it was the same for many of us—at the same time I felt an inner obligation to work for the movement. And then ½ a year of inactivity tore me to shreds—because as a dancer and gymnast one has to keep their body up with training, otherwise you might as well pack it up—so I threw myself into the Reich group just to keep from sinking! —Finally, I found a school where I could learn + train and at the same time even teach ballet, because Laban + Wigmann is very foreign to them73—But on the other hand I always say what is all of this for, do we have time for this sort of thing in the next 5-10 years? —In the courses we put an enormous amount of work into dancing, sport, and gymnastics, but will we be ready? —Shouldn’t I just hang these things up + work solely for the cause! But when I think it over seriously, I always come to the same conclusion—I can’t yet, there is still something inside me, something that urges me to dance, to express creative ideas—just as the painter must paint, and Vitja supports me in this—then come tasks which must be solved, and once again I am torn to and fro—and I race back to the lessons, completely captivated + feel: there, there is where you belong—But I am with our cause—I say to myself, why dance? The most important thing is our movement—Recently I learned of a fabulous woman—a Dane, she works in women’s affairs, for her there really is only “us,” and I admire her, that she can do it—“but I don’t have any career either,” she said, to make it easier for her. In addition to this, I’m learning Russian from Vitja. That is, I have started to, several times, but now we have a small group and it is quite possible he will be sent off to the [Soviet] Union + I will be allowed to follow him, and so it makes even more sense for me to learn the language now—But this is still all very uncertain, what’s the use in racking our brains over it, where will we be sent, where will we go—one can live and set up camp anywhere at all—one is always on the go already, living one day to the next—By the way, Ernst Toller was just here, back from the Writers’ Congress in the Soviet Union,74 was interviewed here + vain as he is, then a ridiculous report came out in “Politiken”75 about “his Leidensweg.” I played a big role in it, he learned nothing from it—And Wollenberg’s book about Toller (Rotarmist vor München)76 is actually quite good—I recall how in our conversations with Fritz about Toller back then in Munich—how vehemently I came to his defense, I was just a little girl you really were the first to wake up! —But it was probably in me already, but I was all just feeling, I hadn’t read anything at all, was still unschooled. Now I am 38 years old, still so young inside, but I’ve always kept going farther, there is only one path for us—I believe you’re probably different from me in many ways—I heard of you once from a friend who worked for Fritz—I wanted to write you right away, but then the trail went cold again—but I thought a lot, a lot about you.

This has turned out to be a much longer letter, it’s so strange—I hardly write anymore, but you’ve brought out so much I simply had to write you one more time—Write to me please, please write me again—

A firm shake of the hand to all three of you from yours—

Ingrid.

Horkheimer to Katja Walch-Lux, 1/31/1935.77

Dear Ingrid,

If I only answer your long and lovely letter with so few lines, it’s because I’m traveling all over the world at the moment and, on top of it all, have an enormous pile of work in front of me. I don’t believe I need to tell you what it means to conduct a whole series of research projects here in this country, negotiate with so many people in a foreign language, and along with all of this edit a scientific journal published in Paris. In the few hours I’m not working, I’m so very tired, and while I’m certainly still capable of thinking and speaking fondly of you, I’m quite incapable of writing. Nonetheless, I was pleased to receive your letter and I ask that you please send another soon. What you’ve said about Reich was of particular interest to me, and you are certainly right. It’s a real shame, because he is an extraordinarily gifted man. Your judgment of him, and everything you’ve said about your activity—this proves you’ve become more mature, and more “manly.” Not a single note rings false, and I was pleased by all of it. Dear old Schnackelberg is still sitting somewhere out there, and I would love to someday see him again.

Warmest regards from us all, but particularly from

Yours—

Katja Walch-Lux to Max Horkheimer and Friedrich Pollock, 2/24/1937.78

My dear friends—Don’t be angry with me that I didn’t reply earlier to to your letter with the money + didn’t thank you right away, but I was very, very sick and yet I was so grateful to you because with this money I could at the very least cover the doctor’s expenses. And so now I say thank you, thank you—This stupid inherited hemophilia has made me so sick + this time I thought I was going to collapse—I had such horrendous nosebleeds for 2 x 8 weeks, the doctor had to stay nights + was at such a loss—he didn’t understand much, he let me lie in bed for so many weeks + wrote all sorts of prescriptions for me—Now a Countess X in [...]79 heard about my case by chance and has taken me under her wing.

She sent me to the best doctor in Sweden, a hemophilia specialist. She paid for the very dear cure + the doctor. I’m getting injected with a protein supplement—and horse serum, I have to lie down so often, to stick to a diet (no smoking + which is the worst!) The doctor diagnosed be with the most severe hemophilia (very rare in women)—I still have a lot of energy, but I’m always so exhausted + weak + have no time to be sick, to know that you’re really not allowed to work anymore is depressing. My life is so uncertain, we can’t all be sick, we shouldn’t all be sick, we must be prepared for what’s coming, and I really don’t want to die yet—!

When are you coming to Stockholm so we can hear more from you and so we can discuss the most various problems—It is even possible that you have a completely different political stance than Vitja + I—We have discussions here with all sorts of people from all sorts of organizations + there are often the most interesting discussions—about the United Front [...]80 unfortunately a number of my friends got the collar there too—But I shouldn’t write about this today—We finally had a proper Nordic winter, but I can't even enjoy it because I can’t go skiing.

The letter is still lying there—but I can’t write, I’m still doing so poorly I’m almost always lying in bed—unfortunately, my energy is waning because I can’t see myself making any progress—A serious weakness of heart has set in now too. And often, at night, I’m seized with the fear I’ll never feel it again, that I can’t go back—Oh, nonsense! One shouldn’t be so depressed!—Fritz once said: “You never have to think about something, Katja!” That was in the English Garden, and he set my head on straight (as he did on more than one occasion!)

40 years old now, and what have I accomplished? —Oh, I’ve really done so little—I could be much much further on today—! No, I can’t even write letters + what else—? But this will really make you angry with that ungrateful old Schnackelberg. Of you my dear friends I always think with special warmth—

Thank you, thank you for everything—

Your old,

Katja

Correspondence with Katja Walch-Lux (1967-1968)

Katja Walch-Lux to Horkheimer, 7/15/1967.81

Dear Max! I’m really far too sick to even be upset—But it upsets me! I can’t just switch off my political thinking at a moment’s notice—Yes, it upsets me, that you and Adorno did not keep the promise you once made to us, and to the students.82 Yes, it takes a lot of courage to stand on the side of the students. Further—to remember that we, too, protested the state of our time. I grant the students of today the same right! Were our methods really always so clever? Weren’t we just as inept? If you don’t understand today’s youth, the students who’ve been depoliticized until now, then you’ve really grown old inside. But you, you of all people, who stands in the public eye, who the students once revered—you ought to have stood by them publicly. That you, Max, failed in such a crucial situation—this I cannot get past—Whether someone will come and post my letter—I don’t know. I had to give my dear canine comrade over to an animal shelter for some time because all I can do is lie here—forgive me—These lines, written in deep sorrow—

Your,

Katja.

P.S. Forgive the sheet of paper.83

But I have no stationary at home—

[Excerpts from:] Katja Walch-Lux to Horkheimer, 5/4/1968.84

Dear Max!

(Typing is not one of my strengths)85

I do want to thank you for the “Nuremberg Discussion” of May 1st.86 Unfortunately the panel discussion from the radio wasn’t complete, it was just extracts from the discussion. Still I was shaken by what you said, that you, as a nineteen-year-old, were incapable of understanding the people’s jubilation when the war first broke out. I felt exactly the same at the time; I went to the English Garden; I couldn’t understand why my comrades were celebrating. More than that—that you honestly admitted you were afraid, you were at a loss for whatever was coming, that you didn’t know how to respond! Strangely enough, I wrote the very same thing to my sister in Zurich on April 23rd. You, just like so many other older people, now seem to have changed your view of the youth. For that I am especially thankful. These youth are just as helpless as we were, as we are. They often commit acts of violence without wanting to, under the threats of the shameless Springer-Press,87 the great coalition against them,88 the all-powerful police. The police and the great coalition—there are still so many Nazis among them. Their methods are certainly fascist. The formerly depoliticized youth only developed political consciousness with the death of Benno Ohnesorg.89 They feel betrayed by the great coalition. It only keeps making promises, e.g. implementing university reforms, etc.

The betrayal is terrible: the youth are permitted to demonstrate in peace, but as soon as they do, they are dragged away onto side-streets by the all-powerful police; when the youth then protest and demand their right to demonstrate, the police surround them and beat them up, their faces contorted by rage, throwing the most defenceless around in the most brutal way, blasting them with water canons and scraped across the streets into cars already waiting for them. The police don’t care that non-demonstrators who stand quietly nearby—journalists, college professors, etc., etc.—are all treated the same. They behave just as the Gestapo did: killing, beating, beating. The demonstrators defend themselves, reaching for stones and whatever else is around. But the apolitical masses standing around on the sidelines still scream: Protect the police from these murderers! These filthy students!

That the Springerkonzern is a dangerous power, read and loved by many government figures, like Strauß,90 Lübke,91 and others—this is already well-known. But this is why the apolitical masses are so dangerous, particularly German women, who believe everything written in black and white. Sure, it’s wrong to set the Springer truck on fire, to bash in the windows of the Springer Publishing House with stones (however—it is highly ensured!) But do we even know if it was actually the students themselves? Couldn’t it have been provocateurs in the NPD?92 Who could possibly make this determination in the aftermath, after such a battle in the streets! The police use dishonest means! For instance—an officer shouted, “An officer has been murdered!” But later it turned out to be only an order to attack, and no officer had been killed. But that only appeared in the pages of the few honest, i.e. upstanding, newspapers. At Springer, the [accusation] made the headlines. If the students actually did throw some stones, then I believe: they did this only to say: here we are, come talk to us already. Kiesinger spoke unbelievably during his election campaign,93 he threatened to ban all demonstrations, the consequence: he was booed and whistled and hooted at. Willi Brandt,94 however, acknowledged his mistakes to the younger generation, and he was applauded. The very next day, Kiesinger came down from his high horse and totally reversed his position: we must find the reasons which motivate such unrest among the youth, it would be best to talk with them about this. Unfortunately, however, all of this is much too late: three have been killed, one was almost assassinated.95 I have higher regard for the last mayor, Albertz,96 who admitted the mistakes he made during the Shah’s visit, and the students thanked him for it. But right now, Schütz is making even graver mistakes.97

Max, I too am afraid of a new 1933!

I cite a few passages from a well-known book!98

(But I already knew this in 1944/45, when I was still living in Stockholm.) —

“H. Lübke, director of a Settlement Company [Siedlungsgesellschaft] before 1945; dismissed without notice for fraud; deputy leader of the Schlempp construction group; V-Mann for the Gestapo, oversaw the construction of KZ-Leau [KZ: Konzentrationslager, viz., concentration camp], subcamp of KZ-Buchenwald. Responsible for the deaths of hundreds of Poles, French, Italians, Soviet citizens, and Germans through slave labor. After 1945: President of the DBR [Deutsche Bundesrepublik], former Federal Minister of Food, Minister of Agriculture of North Rhine-Westphalia—”

“—Bonn's efforts to grant general amnesty to all War- and Nazi-Criminals date back to the beginning of the DBR itself. Just three months after its formation, on December 1st, 1949, a new amnesty law was passed (“Gesetz über die Gewährung von Straffreiheit”). The culmination of such efforts was the “Gesetz über die Berechnung strafrechtlicher Verjährungsfristen,” announced on April 13th, 1965, by none other than DBR president Lübke, V-Mann of the Gestapo headquarters in Stettin and the murderer of KZ-Leau. —”

I could quote passages from the same book about Strauß, about many other high-ranking government officials. All of this has been documented in photocopies, available for DBR inspection at their convenience; but they very wisely declined. I expect you’ve known all of this yourself, and have for a long time. But there are so many academics who are completely ignorant of these things.

How could young students, young workers, respect a government such as this one? Who are they supposed to trust? Surely, there are many academics, and other well-educated adults, scientists, who are committed to the youth, but still far, far too few. The argument so many old people use: first, grow up, and then you might have your say; but first, your studies—is a cheap argument. This is why I think you were right to say: one should form groups everywhere for talking with people young and old about these things. Of course this would mean winning their trust first, listening to their biggest worries, their plans, their often very incisive thoughts; and considering these thoughts of theirs seriously, however absurd some of it might seem to us. The haughtiness and the arrogance they seem to display is only a mask behind which they conceal their insecurity and their helplessness, just as their beards and the way they grow their hair out is meant to make them more manly. I talk with the youth everywhere I go, and to women—who are unfortunately incredibly apolitical, particularly those around thirty and older, interested only in Maxi-/Mini-moden, money, wealth! It’s a complete shock to them when I say, for instance: these youth are only the product of the society in which we live, and every single one of us who continues to remain silent has their share of the blame for how all of these things turned out.

Just yesterday, I had an opportunity to speak with a young ceramicist in our little town. He asserted that 60-70% of the youth were interested in the NPD. When I asked where he was getting this number from, he said: Herr von Thadden said so, that the youth were flocking to him.99 This young man isn’t stupid; but he fell for it just as the Hitler-youth once did. I spoke with him at length, very carefully. As I got up to leave, he asked if I would come back and speak with him again soon. He has just moved into town, and has been very isolated, unable to talk to anyone else. His older brother was NPD, and could only visit on weekends. His father, a Nazi. So I must speak very carefully around him, since I’m still a foreigner,100 and in this one town of 11,000-12,000 residents, nearly 800-1,000 are NPD.

I couldn’t sleep the night after hearing your discussion. I thought back to my last letter to you, about my sadness that you, Max, you turned against the youth. Perhaps what I wrote was unjust and hurtful, but it came from my great disappointment. We’re all so uncertain, how could we be any different? What happens now? What are we supposed to do? [...]

John Abromeit (2004): “Horkheimer was introduced to Krull by one of her friends, Katja Lux, whom Horkheimer met in the Fall of 1918 while browsing in a bookstore in Schwabing. Horkheimer soon became an active participant in their circle, which met regularly in Krull’s atelier. Krull, who was two years younger than Horkheimer, had already made somewhat of a name for herself as the portraitist of Kurt Eisner, a journalist and theater critic who had recently become the leader of the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD), and who would play the leading role in the revolutionary events in Munich, until his assassination on February 21, 1919. Krull’s parents introduced her to Eisner, and after his assassination she remained friends with his widow. Krull’s friend Katja Lux, whom she had met in photography school, was friends with Ernst Toller, a young poet and playwright. Toller would take over the helm of the USPD after Eisner’s death and play a leading role in the Munich council republic the following April. In addition to the Eisners and Toller, Krull was in contact with several of the most respected poets and writers living in Munich at the time, including Stefan Zweig and Rainer Maria Rilke. All of these figures, and many other less prominent members of bohemian Munich, made more or less frequent appearances in Krull’s atelier.” In: The Dialectic of Bourgeois Society: An Intellectual Biography of the Young Max Horkheimer, 1895-1937. Dissertation, University of California, Berkeley (2004), 54-55.

Much of the dissertation is repurposed for Abromeit’s later Max Horkheimer and the Foundations of the Frankfurt School (Cambridge University Press, 2011). I refer primarily to the former because it treats Horkheimer’s development in the late 1910s in greater detail.